Mark Hollis, the lead singer of ÔÇÖ80s synth-pop act Talk Talk, passed away last week after a brief illness at the age of 64. He had a handful of hits during that decade but hadnÔÇÖt been on the charts since 1986 and hadnÔÇÖt released any music in over 20 years. In fact, he had all but disappeared from the public eye and a week later, there are no further details about the cause of death. Yet HollisÔÇÖs passing was spoken of with a level of reverence befitting a spiritual leader.

If you never heard the music of Hollis or Talk Talk and found yourself auditioning their albums via streaming, you may have wondered where exactly this music was. Mark HollisÔÇÖs last album (which was also his first solo album) dates from 1998. It doesnÔÇÖt make a sound for the first 20 seconds and seems comprised of little more than piano and his sighs in a room, yet you feel like you are seated on the piano bench next to him. Talk TalkÔÇÖs swan song, 1991ÔÇÖs Laughing Stock, is similarly diffuse, the trembling strings and horns ÔÇö┬áas well as guitar and drums ÔÇö moving like spilled mercury through any attempt at song structure. Nevertheless, you feel immersed in a great body of water. Their 1988 album Spirit of Eden opens with fluttering strings, brass, and the ambience of a submarineÔÇÖs hull, every element bordering on the verge of either feedback or silence. ItÔÇÖs two minutes in before a guitar chord chimes and well past the three-minute mark before Mark HollisÔÇÖs fraught and fragile voice quivers to life. Along the way, Hollis and band alight on the orchestral jazz that Miles Davis and Gil Evans achieved, the acidic Chicago blues of Little Walter, the distilled sound of composer Morton Feldman, drawing on it all and reaching a rarefied peak in its nine minutes. And just as ÔÇ£The RainbowÔÇØ coalesces into a song, it nearly vanishes, slowly reemerging from silence, again and again, unhurried yet graceful in its movements.

ItÔÇÖs this sort of masterful balancing act ÔÇö┬ábetween a sonic maelstrom and secluded monastery ÔÇö that made Mark Hollis into a sainted figure, even after he turned his back on music forever after 1998. As he told the Wire at the time about that transformation: ÔÇ£It was just not wanting to repeat what youÔÇÖve done. All the time, youÔÇÖre getting older and everything and nothing is static. It feels far more bizarre to me that there should be no change. That feels really very weird to me.ÔÇØ So in one way, it wasnÔÇÖt weird that soon after that, Hollis preferred silence over all. Tributes have poured in from the likes of Peter Gabriel, Tears for Fears, Fleet Foxes, Vampire Weekend, and the Arcade Fire. And while itÔÇÖs easy to draw a line from Talk TalkÔÇÖs biggest hit, 1984ÔÇÖs ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs My Life,ÔÇØ to No DoubtÔÇÖs smash cover two decades later, Talk TalkÔÇÖs influence on rock and electronic music feels both seismic and almost impossible to readily trace. Mark Hollis slowly disappeared from pop music culture and at the same time transcended it to become part of its subconscious.

ItÔÇÖs impossible to imagine what the likes of Radiohead, Spiritualized, Sigur R├│s, Slowdive, Explosions in the Sky, and generations of post-rock bands and 21st century producers would sound like without HollisÔÇÖs meticulous and transcendent example. That sense of adventurousness, the pursuit of sound as an end in itself rather than a hunt for the next hit single or new sound, that patient sense of dynamics, able to lullaby or combust at any moment, these were not common traits for a band to have by the late ÔÇÿ80s and early ÔÇÿ90s.

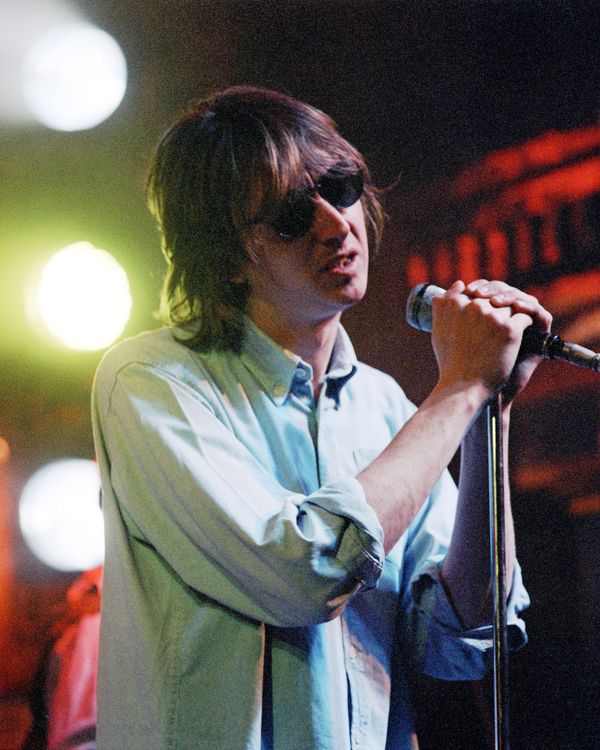

If you first encountered Talk Talk on the radio in the early 1980s, none of these traits were evident to your ears. The band was part of the New Romantic movement of British synth-pop, not readily distinguished from peers like Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet and Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark. One magazine snorted, ÔÇ£Typical Typical,ÔÇØ adding, ÔÇ£the mediocrity is the message.ÔÇØ From the vantage point of today or even the start of the 1990s, hooky early singles like ÔÇ£Talk TalkÔÇØ and ÔÇ£Such a ShameÔÇØ sound well-crafted if weirdly formulaic. For those who hear in Mark Hollis a state of zen, seeing him cavort onstage bare-chested in a denim jacket in 1984 is hilarious. Similarly, if you were a fan of their skinny-tie singles (or, say, a music executive at a record label), the music that followed is downright mystifying.

Through these albums  each one has felt like a very natural progression from where the one before was, Hollis said in the same interview. But  to the first one, theres no relationship there at all. By 1988s Spirit of Eden, the band sounded wholly unlike itself. They certainly didnt sound like their synth-pop peers, much less the iconic albums of that age. The biggest albums from then are dense, intense, sprawling affairs. Whether you cite the likes of It Takes a Nation to Hold Us Back, Daydream Nation, Loveless, Blood Sugar Sex Magik, And Justice for All, or Achtung Baby, Spirit of Eden sounds like its from another planet. And when Talk Talk released Laughing Stock on September 16, 1991, they were in a parallel universe. The very next day, Guns N Roses released Use Your Illusion I & II. GNR was similarly ambitious and went beyond the confines of guitar, bass, and drums in deploying piano, horns, choirs, organ, and more. Talk Talk utilized upwards of 18 musicians; GNR credits 19. Some of Illusions songs also sprawl past the nine-minute mark, but they lumber like a steam engine down the tracks, sodden and heavy. Even the longest song on Laughing Stock seems to float toward heaven, weightless even with all the sounds contained within it.

The change that Hollis and Talk Talk underwent over the course of the 1980s is hard to properly convey, the gulf between where they started out and where they finally dissolved almost unfathomable. So letÔÇÖs go back to that image of Hollis shirtless in a jean jacket onstage in 1984 singing ÔÇ£Dum Dum GirlÔÇØ: what if I told you that by the year 2022, Greta Van FleetÔÇÖs Josh Kiszka would release the most profound and visionary music of the next 30 years? ThatÔÇÖs the metamorphosis of Mark Hollis.

But even 1986s The Colour of Spring reflects that theme of change. Their synth-pop side sloughed off like a chrysalis, with a childrens choir, piano, electronic wind instruments, and a profound use of space emergent. In the paintings by James Marsh that adorn these albums, vivid images of butterflies and birds brighten otherwise bare trees. Come gentle spring  Gone is the pallor from a promise thats natures gift, Hollis sings of that new season of life, and over the next three albums, his words and music would more readily reflect an inward turn.

Spring is symbolic in more ways than one. Take the sublime nine-minute masterwork ÔÇ£New Grass,ÔÇØ with its stately strings and ebullient guitar line that gurgles up like a spring: ÔÇ£Lifted up / Reflected in returning love you sing / Heaven waits, Heaven waits / Someday Christendom may come.ÔÇØ┬áItÔÇÖs at a sublime moment like this that the entire notion of Christian rock feels moot. The Holy Spirit moves within the music, though he swore to the Wire that, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm not a born again Christian, no, but I would hope thereÔÇÖs a humanitarian vision in there.ÔÇØ

Holliss music struck another balance, between the human and the spiritual. Im not saying all lyrics have to be about religion but, in a way, there must be that kind of thing in it, he told Melody Maker. Silence is the most important thing you have  [and] spirit is everything. Mystical Christianity and imagery worthy of William Blake, redemption, atonement, a quest for purity; these qualities are imparted across these last three albums from Hollis and Talk Talk.

Spirit of Eden, Laughing Stock, and his lone solo album stand as HollisÔÇÖs last statements, a triptych unmatched in popular music. Try as one might to slot them in with artistic achievements along the lines of Nick DrakeÔÇÖs Pink Moon or Joy DivisionÔÇÖs Closer, the tragedies that haunt those albums is a different sort of muting. Hollis seems to have reached a different conclusion, one that brings to mind the canvasses of Rothko Chapel, the late string quartets of Feldman. He achieved something that transcends category and instead hints at the ineffable. Even in the decades of silence that followed and a life that ended in the misery of a February winter, one hopes that Mark Hollis caught a glimpse of the spring to come before exiting from this world.