It was a bit of a battle for A.N. Devers to convince her landlord to let her introduce so much pink into the Second Shelf, the ÔÇ£accidental,ÔÇØ internet-famous brick-and-mortar bookstore she opened last November in LondonÔÇÖs retail-centric Soho. Hidden down the sort of narrow passage you only find in ancient cities, and tucked away into a paved, vaguely Victorian courtyard, thereÔÇÖs a Narnia-esque magic when you find it, as if the archway you stepped through may have only existed in the moment right before you crossed over.

The store isnt pink, she explains, to pander to some outdated idea about femininity. To be honest, says Devers  the 42-year-old writer, editor, and dealer of rare books by women  as we sit very, very closely on a striped settee, the only seating in the miniscule space, Im not the girliest girl. I dont wear a lot of pink  Its not my favorite color. She sees it as a radical choice, considering the old-boys-club aesthetic that reigns at so many antiquarian book shops. Devers wants shoppers to feel comfortable, to pull very expensive books off the shelf without worrying about it. And, she admits, laughing, she also just loves how punk it feels to transform a stereotypically refined space into a modern vision of what a rare-books shop can be.

In just under a year, Devers has become the face of a movement to reevaluate and revalue rare books written by women. SheÔÇÖs the new patron saint of more than just collectors, though: Her relentless devotion to honoring female writers and their fans has turned her and her shop into digital and analogue destinations. The fashion writer Cathy Horyn recently stopped by and ended up inviting Devers to the Dries Van Noten runway show in Paris. Roxane Gay swung by in the winter. Shoppers excitedly tweet out photos of their purchases and the shop front itself, delighted to have interacted with a space that savvily marries their passions ÔÇö feminism and literature. The Second Shelf is part shrine, part unofficial clubhouse for the female literary set.

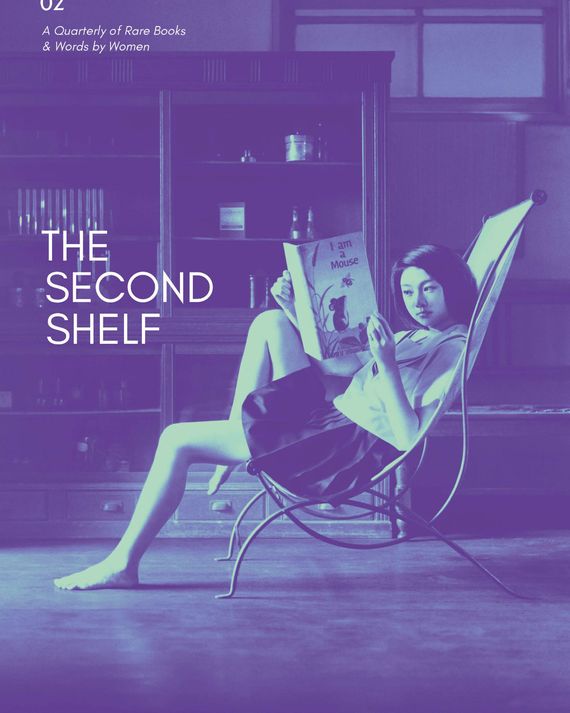

In real life, the Second Shelf is cluttered in the way a rare-books shop ought to be, with a small corner dedicated to DeversÔÇÖ Smeg electric kettle (also pink), which she immediately fires up when I arrive, and antique barrister bookshelves holding literary curiosities like Sylvia PlathÔÇÖs cherry-red wallet ÔÇö it includes the silver dollar she always carried for luck ÔÇö and a Victorian ladyÔÇÖs elaborate musical composition book. The shopÔÇÖs exterior is a muted red, which Devers describes as a ÔÇ£compromise.ÔÇØ The interior feels like the inside of an actual novel, with marbled endpaper wrapping every wall in dignified excitement. The landlord, she explains, ÔÇ£tried to keep me from having pink floors,ÔÇØ but through sheer force of will she won them over; mauve tiles match the painted shelves and complement the fuchsia covers of the the Second ShelfÔÇÖs quarterly magazine-cum-catalogue.

The bookshop was never in DeversÔÇÖs plans. Three years ago, she moved from New York to London after two decades in various careers: She was an archaeologist, the publicity manager for the Brooklyn ChildrenÔÇÖs Museum, a writer, and, yes, at one point, a bookstore clerk at MinneapolisÔÇÖs now-shuttered Ruminator Books. ÔÇ£There is a [rare books] fair somewhere in England almost every weekend,ÔÇØ she explains, so when her preoccupation with collecting and selling kicked in, it made sense to base herself across the Atlantic. In an essay she wrote for The Guardian last May, Devers explains that on one of her initial visits to a book fair, she slid a rare edition of a Joan Didion novel off the shelf: The bargain price of $25 was pencilled on the inside cover. Next to it, a Cormac McCarthy novel commanded $600. She wondered how that could be. Didion is an American icon: Her essays revolutionized the form, and sheÔÇÖs famous enough to have leapt the barricades of literary stardom right into a Gap ad and a C├®line ad. McCarthy, too, is regularly called up as one of the great innovators of American fiction. But is his work worth 24 times DidionÔÇÖs?

Correcting that yawning gap between the perceived value of rare books by men versus women propelled Devers to wade into the industryÔÇÖs business end. In 2016 Deborah Davis, the founder of London-based Love Rare Books, invited Devers to sell a few of her pieces at a fair. The sellers, Devers says, were about ÔÇ£80 to 90 percent male,ÔÇØ and women sellers were ÔÇ£very cordoned off ÔǪ They either sold childrenÔÇÖs books or a smattering of whatÔÇÖs considered ÔÇÿcreativeÔÇÖ or ÔÇÿdesignÔÇÖ books.ÔÇØ SheÔÇÖs very quick to tell me there are, in fact, a good portion of women in the industry, that theyÔÇÖve been chugging along for years, and that women like the dealer Elizabeth Crawford ÔÇö who has specialized in womenÔÇÖs books since 1984 ÔÇö have been instrumental in helping Devers get started. ÔÇ£I was quite na├»ve,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£I didnÔÇÖt know ÔǪ before I moved to London that there were women-focused book dealers.ÔÇØ And she insists repeatedly while we talk that she doesnÔÇÖt see herself as a pioneer in the industry. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm not the only person trying to make change in the rare-book world for women at all.ÔÇØ She goes on, ÔÇ£But I saw our current social-media opportunity of putting myself out there as a way to make the business happen.ÔÇØ

It worked. Visitors show up at the shop after glimpsing it on Instagram. A viral tweet in January brought the shop so much attention that she credits it with keeping her financially afloat. Devers has gamely ÔÇö and very smartly ÔÇö utilized every outlet available to her, and hasnÔÇÖt aimed her attention toward the rare-book world itself. Instead, sheÔÇÖs capitalized on what women want ÔÇö merch that boasts female empowerment, like the ÔÇ£BookwomenÔÇØ tote bags she sells in the shop; a rich and deep reverence for women-created art; and, most importantly, for their literary passions to be taken seriously.

Nearly every book in the Second Shelf ÔÇö a name Devers borrowed with enthusiastic permission from Meg Wolitzer, who wrote a New York Times essay under that title bemoaning the second-class treatment of womenÔÇÖs literature ÔÇö is a first edition, and nearly all are by women writers. The expected greats are there ÔÇö a covetable ┬ú600 dust-jacketed version of Virginia WoolfÔÇÖs The Common Reader, complete with Vanessa BellÔÇÖs swirling cover design ÔÇö along with newer works like Rachel CuskÔÇÖs ÔÇ£FayeÔÇØ trilogy, which are usually priced around ┬ú20 to ┬ú40, depending on their condition and whether or not theyÔÇÖre signed. Devers says they ÔÇ£[fly] off of our shelves.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs also a ┬ú20,000 three-volume set of Jane AustenÔÇÖs Sense and Sensibility that belonged to the legendary novelistÔÇÖs dear friend Martha Lloyd, ÔÇ£one of the few people privy to JaneÔÇÖs secret desire to write.ÔÇØ Penguin paperbacks, with their graphic orange-and-black covers, are priced to sell for six quid apiece.

Two dark-haired women ÔÇö they could be sisters ÔÇö come to the door while weÔÇÖre chatting. ItÔÇÖs Sunday, and the shop is closed, but Devers welcomes them in. They blow in with a gust of cold air and immediately gasp and giggle with delight. ÔÇ£We are so glad we found you,ÔÇØ one proclaims, ÔÇ£because we thought we wouldnÔÇÖt!ÔÇØ They move slowly through the room, leaning into the shelves and sliding books forward, pointing out the names of writers they admire. They donÔÇÖt buy anything, but Devers warmly sends them off with a reminder that the books ÔÇ£make beautiful presents.ÔÇØ Both women nod rapidly and promise theyÔÇÖll be back.

As a small-time collector myself, I admit some sticker shock when I flicked open that copy of WoolfÔÇÖs The Common Reader; the subsequent mental conversion from pounds to dollars put it well out of my range. Then again, Woolf is one of the biggest names in the industry, and an intact dust jacket immediately ratchets up the price of any first edition. Devers makes the case ÔÇö quite convincingly ÔÇö that such books arenÔÇÖt overpriced, theyÔÇÖre finally properly priced.

ÔÇ£The backhanded compliment I get [from male sellers] is, ÔÇÿYou found your niche,ÔÇÖÔÇØ she says with a shake of the head and a cocked eye. ÔÇ£And then I say, ÔÇÿWomen are not a niche, but yes, I have.ÔÇÖÔÇØ But instead of niche, Devers has actively sought diversity in every form. Work by women of various eras, races, styles, formats, notoriety, genres, identities, and politics fill the shelves. She walks me through the room, pointing out titles and authors. At a charity shop in London she found a novel by Miriam Tlali, the first black South African woman to publish in that country. ÔÇ£I bought as many copies as I could of that book and all of those have sold. And then I bought 15 copies or something like that of her book of short stories. And weÔÇÖre down to having I think one in the store.ÔÇØ ThereÔÇÖs a hefty copy of Pauline KaelÔÇÖs Hooked, one of her many volumes of film criticism. Just above is some Siri Hustvedt, down the shelf is a selection of R. Prawer Jhabvala, and below is a brand-new copy of Min Jin LeeÔÇÖs Pachinko from 2017. She canÔÇÖt keep Toni Morrison in stock.

The brick-and-mortar shop only came into existence after the spaceÔÇÖs landlords made an appealing offer to Devers: greatly discounted rent. Initially, the Second Shelf was imagined as an online retailer, with the quarterly as accompaniment. A Kickstarter launched in May 2018, and reached its goal in 20 days. Eventually, over 600 backers pledged more than ┬ú32,000 to the venture, raising over 50 percent more than Devers had hoped for. More than anything, Devers needed buzz: ÔÇ£I thought that if I only ever had 20 books [and] if I just kept selling them, no one would ever get the message ÔǪ The only way that I was going to launch this business in a way that would make it sustainable for me and not cost me a fortune was to make a bit of a splash with it.ÔÇØ

The digital shop is forthcoming ÔÇö Devers hopes to launch it next week. ItÔÇÖs clear while IÔÇÖm visiting that the Second Shelf is a hustle far more rigorous than it looks from the outside. When she announced the ventureÔÇÖs launch, Devers also explained in a series of tweets that sheÔÇÖd had a hysterectomy right before coming to London, and that sheÔÇÖd also been laid up in bed with a series of medical ailments. A large portion of her forthcoming book, Train, was stolen from her car while she was dropping her son off at school just two days after the store opened. It hasnÔÇÖt been recovered. Devers runs the store, buys all of its stock at book fairs around England, edits the quarterly, is working to facilitate relationships with libraries and collectors, and researches just about everything that comes through the door.

She fervently emphasizes the large cast of women who work behind the scenes. ÔÇ£A lot of the Kickstarter money,ÔÇØ she says, ÔÇ£went into the pockets of women illustrators, women photographers, women designers. I hired all women. There was one male who did a recording, that was it.ÔÇØ Everyone is paid. The cast of women brought onboard to advise the venture is a murderersÔÇÖ row of female authors: Lauren Groff, Elizabeth McCracken, Cheryl Strayed, and Jesmyn Ward, and the critics Laurie Muchnick, Rachel Syme, and Sarah Weinman. She brought on the British critic Lucy Scholes to manage the quarterly; Scholes also commissioned the majority of the pieces in the upcoming issue (available for preorder now), which is devoted to female illustrators like Pamela Colman Smith, who famously designed the Rider-Waite tarot, and feminist magical realist Angela Carter of The Bloody Chamber fame.

Devers walks me out into the gloam, and as we stand in the tiny cobbled courtyard, she explains what shops will eventually fill each storefront. We spin clockwise ÔÇö thereÔÇÖs a caf├®, an independent jeweler. Laughing, she tells me that the shop directly next to the Second Shelf has gone from red to blue, just as her storefront went from blue to red. It will be a ÔÇ£gentlemanÔÇÖs general store.ÔÇØ

ÔÇ£Well,ÔÇØ she says with a wry smile, ÔÇ£I guess weÔÇÖre a perfect match.ÔÇØ