“This,” Ollie Jones explains, “is our first and possibly our last ever 300 percent butt piece we’ve ever built.” The special-effects supervisor gestures toward a combination of metal rigging, fabricated fur, and stretched clothing, all of which was used for a single close-up in the stop-motion animated movie Missing Link. The “overscale” piece, almost unrecognizable as a rear end, is much larger than the average nine-inch-tall Bigfoot puppets scattered elsewhere in Jones’s rigging laboratory. “This is for a scene where Mr. Link is kind of, like, doing calisthenics,” Jones continues. (Mr. Link is the film’s titular Bigfoot.) “He’s about to try and jump over a wall, so he bends over and his pants split open.”

The wildly intricate setup, so detailed that you can see the unique threads that snapped to bear Mr. Link’s posterior tufts of fur, will appear onscreen for just one or two seconds. “It’s a lot of work for not a lot of frames,” Jones says.

Of course, that’s the M.O. for stop-motion animators, beholden to an intricate process that involves shooting each frame of action individually, making tiny physical adjustments to reflect the next hip bend or fabric tear, and then shooting again. Seen in rapid succession, the shots look like natural, fluid movement — like actual pants ripping at the back seam. But there are actually 24 frames in each second of footage, and 60 seconds in each of the 94 minutes of Missing Link. You do the math.

The meticulous, labor-intensive process of stop-motion is something of an anomaly in these days of computer-generated animation. But the people at Laika, a stop-motion animation studio near Portland, Oregon, like it that way. “As kids come out of the theater nowadays, I think a lot of time they’re just telling their parents, ‘Oh, that’s cool, but that was just done on the computer,’” says Brian McLean, Laika’s director of rapid prototyping. “I think there’s something about stop-motion that’s so tactile. Kids come out of a film still having no idea how we did it. As soon as they hear that it’s actually a little nine-inch puppet that humans brought to life frame by frame, it’s this ‘Holy crap! Movie magic!’ moment.”

Missing Link is Laika’s fifth animated feature, following Coraline (2009), ParaNorman (2012), The Boxtrolls (2014), and Kubo and the Two Strings (2016). Pitched as “a little bit Indiana Jones, a little bit Sherlock Holmes, a little bit Planes, Trains, and Automobiles, and a little bit Around the World in 80 Days,” the movie follows explorer Sir Lionel Frost and his unlikely travel companion, an eight-foot-tall yeti named Link, who together are searching for the birthplace of Bigfoots: Shangri-la. “This is definitely the most ambitious thing we’ve done,” says Chris Butler, the film’s writer and director. “We say that every time, but every time it’s true.”

If it sounds like he’s giving the picture a hard sell, it’s understandable. Laika’s films are critically acclaimed and Oscar-nominated, but they have yet to conjure a commercial smash on the order of Disney or Pixar (or DreamWorks or Illumination). Each of Laika’s four features has grossed slightly less than its predecessor, and those were distributed by the well-established Focus Features. Link is Laika’s first release with the smaller Annapurna Studios, which has problems of its own.

So there’s a lot riding on Link. Its creators are understandably pushing it as more mainstream than the work that came before it. “On the face of it, it’s lighter and brighter,” says producer Adrianne Sutner. Butler concurs: “It’s more playful, for sure. More accessible. But there’s still elements of irreverence in it because I can’t help myself.”

“It’s not that our brand is creepy,” Butler continues, immediately summoning images of Coraline’s grisly button eyes. “That’s the thing with stop-motion — historically, it’s always had these dark overtones … I think it’s inherent in the medium. People animating inanimate objects, it’s almost necromantic.”

This sense that Laika is an outlier, existing on the fringes of animation society, is furthered by the studio’s geographic location. It’s neither headquartered in Hollywood nor Silicon Valley, but in Hillsboro, Oregon, a good half-hour drive through the evergreens from Portland. When I talk to people there, it seems the isolation is less a conscious decision and more a product of how things worked out. Laika grew out of Will Vinton Studios, the Claymation company responsible for the ubiquitous California Raisins commercials of the 1980s. Travis Knight, the company’s current president and CEO (and director of Kubo), had reason to keep the company where it started — his father is Nike’s Phil Knight, and their family business is Portland-based.

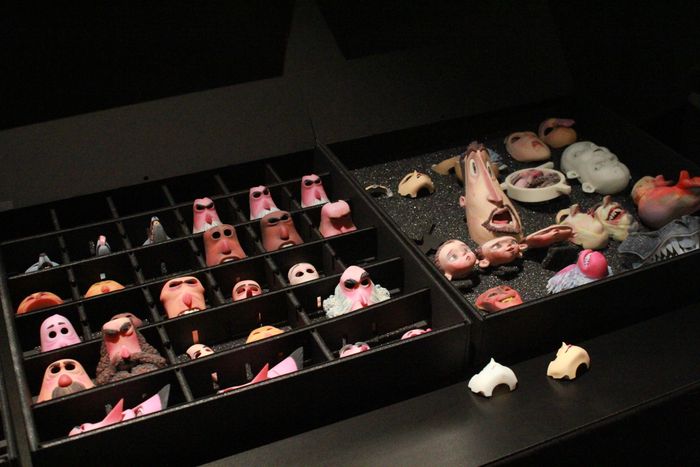

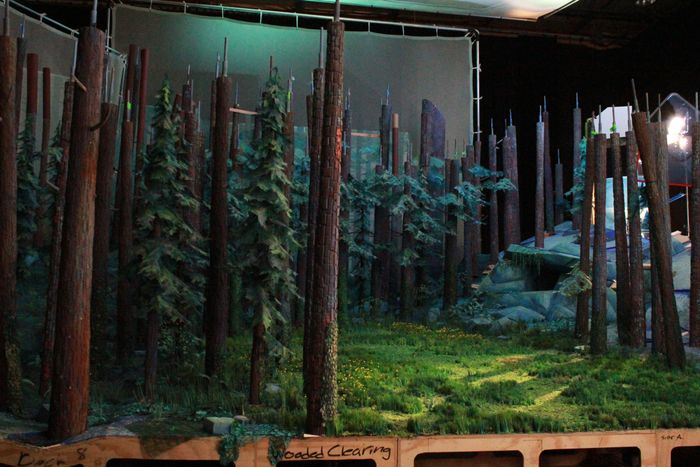

Thus, off in the Pacific Northwest, you have this “smattering of art-school rejects,” as Laika creative lead John Craney puts it, handcrafting costumes, building sets, and 3-D-printing replaceable faces to pop on and off the puppet bodies. A core group of 200 or so people live in Portland and work in Hillsboro year-round, making Laika one of the few contemporary film production companies that operates like the old studio system. (Many film technicians today work on a contract basis, floating from one project and one studio to another.) The giant facility permitted by the relatively cheap Portland real-estate market allows employees, at peak production, to build dozens of sets and shoot multiple scenes all at one, duplicate puppets and costumes waiting in storage on the sidelines.

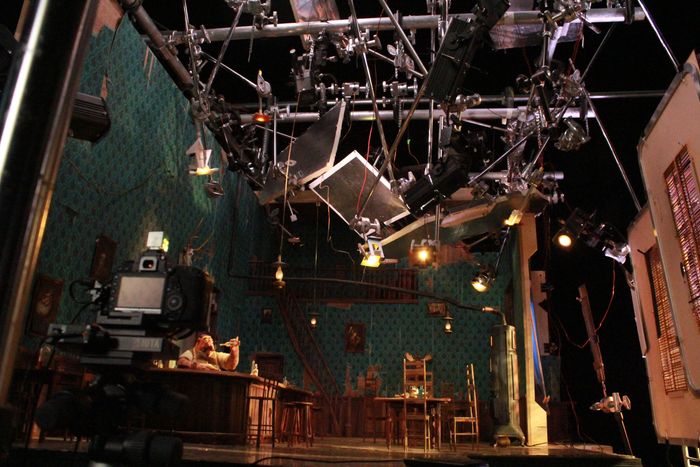

A Laika set in motion is a sight to behold. The puppets that become the studio’s movie stars are mounted on elaborate metal “rigs,” like the one that held Mr. Link’s pants together, to allow maximum range of movement. Each frame of movement is shot in RAW format using a Canon still camera, and each camera is connected to a Mac desktop computer helmed by an animator who approves the shot and sends it down the pipeline to editorial. “Depending on the shot length, it takes about an hour to get the shots into editorial so Chris [Butler] can cut in real time, and we can also view them in the theater in 3-D,” explains Dan Pascall, Laika’s marketing production manager. “We’re shooting in 3-D but we can’t get two cameras close enough together because our increments are tiny.” To solve the problem, Laika developed an automatic slide mount for the camera for Coraline, and have used it ever since. The camera will take one image for the right eye, slide across a couple of millimeters to shoot the same image for the left eye, and then slide back.

It is, as you can imagine, time-consuming. “Our animators’ target is 4.3 seconds per week of approved footage, in the can,” Pascall tells me. “That’s target. That’s in an ideal world, all very well. If you’ve got three or four or five characters being shot together — or you’ve got the elephant walking and three, four characters on top of the elephant, and it’s a character itself — obviously that average can come right down because there’s more moving parts to take care of. So target is 4.3 seconds a week, but the real average is usually between two-and-a-half to three-and-a-half seconds in the can, which is why we’ve got a 92-week production shoot.”

Voice performances are recorded in advance of the strenuous shoots. Missing Link’s cast is impressive, including Zach Galifianakis, Hugh Jackman, Zoe Saldana, Emma Thompson, and Timothy Olyphant. Animators edited their work to the actors verbal tics. Music and sound effects are added after. Then the VFX team goes to work, seamlessly integrating digital backgrounds, characters, and shot extensions, removing the metal rigs that held the puppets in place.

The result is, frankly, a stunning achievement. Missing Link is a film unlike any of Laika’s previous works, which already didn’t look like anyone else’s. Its settings and characters are fantastical, but somehow also appear “real”; the books and papers in Sir Lionel’s study seem worn and weathered, the woods where Mr. Link dwelled for all those years seem lived-in. But what’s most striking is the expressiveness of the characters, how thousands of microscopic adjustments amount to a warmth and kindness glinting in Mr. Link’s eyes and smile.

Despite all the intense physical labor on set, when VFX head Steve Emerson talks about his work, he falls back on a familiar refrain: “We help tell stories.” Other department heads use similar language, discussing the intricacies of the work always within the framework of “storytelling” or “performance.” After all, their movies wouldn’t resonate with audiences if they were simply the products of arduous, clinical work. The tales driving every 4.3 seconds of action must rest on emotions — in the case of Missing Link, on the loneliness of an outsider, and the fearlessness required to transcend it.

The question is if Laika’s handcrafted stories can find a foothold in the current landscape of family entertainment, in which every studio wants its own Pixar-style, Happy Meal–friendly hit, perhaps a symptom of a monoculture only tightened by Disney’s recent acquisition of Fox (and, thus, its Blue Sky Studios subsidiary). Butler remains either tight-lipped or optimistic. “When it comes down to it, I am a film and animation fan,” he says, “so all the stuff that’s going on is very exciting to me.” Sutner agrees: “There are incredible places out there, as you know — you’re seeing these movies. And they do what they do so well. But I think nobody else is doing exactly what we’re doing so well.”

She’s right. What Laika is doing is unique and distinctive; even the British studio Aardman, famous for Wallace & Gromit, dabbles in conventional, computer-generated animation. There was a time when Laika’s insistence on forging its own dark path, out there in the middle of Oregon, earned it a fair amount of rightful admiration. Its image as a button-eyed necromancer in an otherwise tame industry served it well. Today, that same company is releasing a wholly original, but noticeably cheerier story, trousers-wearing Bigfoots and all. Hopefully, audiences — the ones that helped turn Despicable Me 3 and Ice Age 5 into hits — will take notice.