This article was originally published in April 2018 and we are republishing it as part of our coverage of Avengers: Endgame, which prominently features Thanos.

“I’m not an angry person, which you can probably hear from just me talking to you,” Jim Starlin tells me over the phone. Then he sighs. “But Marvel tends to bring out the worst in me, at times.”

That’s a bitterly ironic statement, given what the multi-billion-dollar Marvel brand owes to Starlin. The 70-year-old writer-artist is a giant in the comic-book industry, with hundreds upon hundreds of credits to his name. He’s primarily known as the leading light of so-called “Marvel Cosmic,” the general term applied to the company’s printed tales of trippy adventuring through the far reaches of time and space. Most important, he’s the guy without whom this month’s Marvel mega-blockbuster movie Avengers: Infinity War couldn’t have happened — in the pages of his comics, he created its supervillain, the intergalactic killer Thanos, as well as its magical MacGuffin, the Infinity Gauntlet.

And he swears he’ll never make another comic for Marvel again.

To be clear, his main grudge is with Marvel Comics, Marvel’s publishing arm, not the filmmakers at Marvel Studios. But even that is a recent development — just a few years ago, he threw shade at Marvel Studios for paying him an unsatisfying amount after using his characters in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. He reached a financial détente with them, but his feud with the comics folks has only grown. In December, he announced on Facebook that a recent editorial dispute has led him to decide he’s “moving on” from the publisher.

It’s a situation that’s awkward but far from unprecedented. Starlin has a relationship with Marvel Comics that stretches out over four and a half decades, and it’s long been a turbulent one. He’s acrimoniously quit working for the publisher no fewer than six times, periodically coming back largely because of his love for creating Thanos stories. Now, on the eve of Infinity War — what should have been the apotheosis of his time with Marvel — he thinks relations are worse than they’ve ever been. “I’m not working for them anymore and this time, I think that it’s for good,” he says. “Because this last [dispute] was exceedingly bad.”

On its surface, the present disagreement may seem like a tempest in a proverbial teapot. Indeed, to a layperson, it might be hard to even understand what’s going on. There have been, confusingly enough, two unrelated, ongoing comics storylines involving Thanos. One took place in a monthly series called Thanos, most recently written by Donny Cates; the other in sporadically published graphic novels written by Starlin. In Starlin’s estimation, Cates’s story took on “a strikingly similar plot” to his own plot for the graphic novels (he declines to get into details about what he means for fear of spoilers), and Marvel editorial has not been able to explain to him how that convergence came to be.

Given that Cates’s story was going to publish before Starlin’s, the latter felt like he’d be upstaged by the former. He doesn’t accuse anyone of ripping off his idea, but says “there was plenty of time to fix it” and “they never lifted a finger to correct it.” “My attitude is, if they start undermining your work, especially slating it so it comes out before your job, it’s time to move on to something else,” he told SyFy in February. “And that’s what I’m doing.” (Marvel declined to comment for this article.)

In order to understand Starlin’s fury, one needs to look back at the recent events in context, as the latest in a long line of perceived slights from the publisher. He’s been steeped in comics since his Detroit boyhood, when he fell in love with the 1960s Marvel work of two other writer-artists who had rocky relationships with the company, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. “I got hooked on comic books early,” he says. “My father worked for Chrysler and he used to bring home all this tracing paper from his drafting job, so I started tracing things out of the comic books.” His skills grew and, while serving a Vietnam-era tour of duty with the Navy in the Philippines, he started sending submissions to Marvel and its eternal rival, DC Comics. “Nothing but rejection letters,” he recalls.

His comic-book fortunes abruptly changed soon after he was discharged in 1971. He was in a creative — but volatile — headspace at the time. “I was pretty messed up after my time in the service, came back to the States wired to the max with an explosive temper and an unbearably raw hunger to create great comics,” Starlin writes in his 2010 art book/memoir The Art of Jim Starlin: A Life in Words and Pictures, which Aftershock Comics is about to rerelease. He kept cranking out submissions while working odd jobs and taking some junior-college classes in the Detroit area, and DC editor Joe Orlando finally gave him a shot by publishing a pair of short horror stories.

Elated, Starlin packed up for New York City and, upon arriving, discovered that Marvel was hiring. The first date in their long, troubled romance escalated swiftly. The green 20-something got hired to do some pencilling work, but also acted as an artistic gofer, doing touch-ups on near-finished comics and conferring with Marvel impresario Stan Lee to sketch out cover ideas that more established artists would actually draw. As he puts it, “It was a weird beginning.”

And, in the long run, a profitable one, thanks to the quick arrival of Thanos. Just a few months into his time at the company, Starlin was tasked with drawing an issue of The Invincible Iron Man alongside his friend and housemate, the writer Mike Friedrich. He had just the idea for it. While attending a psychology class in junior college in order to woo a woman, Starlin had become briefly acquainted with the Freudian concept of Thanatos, humanity’s drive for death and self-destruction. As a result, even before he started at Marvel, he’d drawn up plans for a villain named Thanos, using that subtracted spelling “because it ‘looked’ better in print.” (For all the nitpicky geeks out there: Starlin swears up and down that any resemblance to contemporaneous Jack Kirby villain Darkseid was purely coincidental.) The time had come, he felt, for Thanos to make his debut.

According to Starlin, when the Iron Man opportunity popped up, he ran to editor Roy Thomas with the idea, got the green light, and rushed home in a fervor. “Mike and I agreed that we’d talk over a plot later that night,” Starlin writes in his book. “But when Mr. Friedrich arrived home, he discovered I already had three pages of The Invincible Iron Man #55 completed.” Starlin also wanted the story to introduce another character he’d been hashing out, Drax the Destroyer, who has (albeit in greatly modified form) appeared in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, too. Friedrich recalls how excited Starlin was to be adding Drax and Thanos to the Marvel dramatis personae: “It wasn’t a casual thing,” Friedrich says. “Jim had come to New York with these characters and he wanted to do them for Marvel. In his mind, these were Marvel Comics characters.”

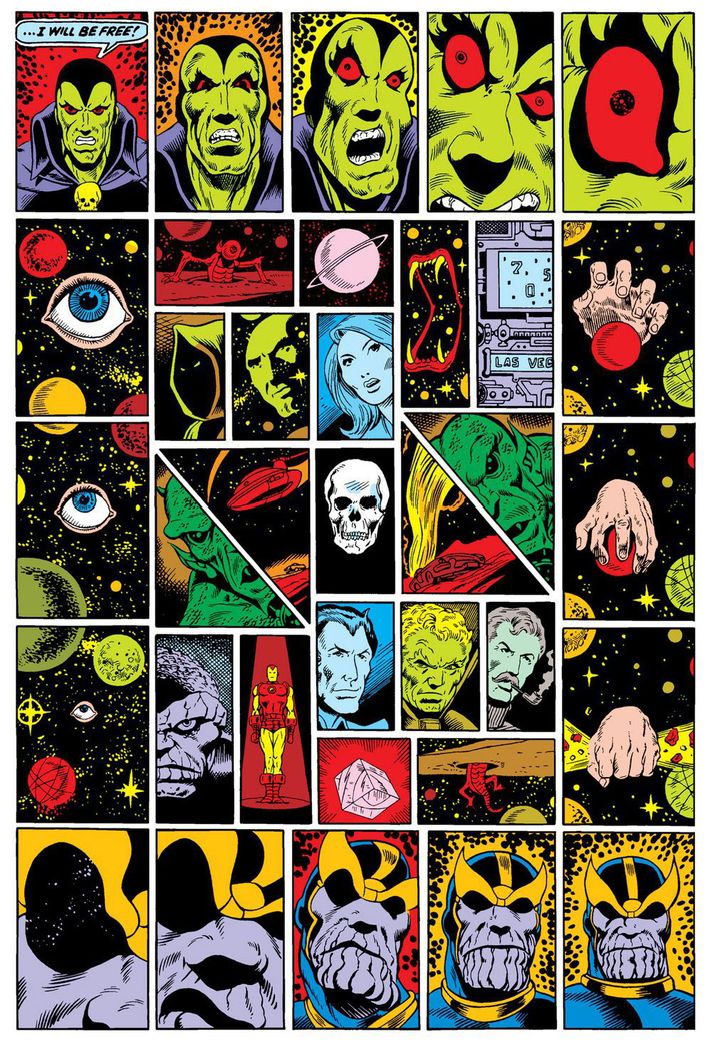

And, when the issue hit newsstands in December of 1972, Starlin’s wish for his brainchildren came true. Entitled “Beware the … Blood Brothers!” the one-off story was a little loopy, but its verve was undeniable. It’s told out of chronological order, opening with extraterrestrial warrior Drax sending a telepathic message to Iron Man while the latter is being attacked by the titular brothers — minions of the as-yet-unseen Thanos — then jumping backward to show how our metal-clad hero got into this situation. After a download of exposition about how Thanos was the child of a benevolent alien king named Mentor and brother of a being named Eros (not coincidentally, the name of Freud’s positive counterweight to Thanatos), cast out for his desire to wage war, the baddie finally appears. “The name, Iron Man, is … Thanos!” he declares. “More properly, Thanos the first — emperor shortly of near-defeated Titan — then of your own Earth!” Drax and Iron Man take him out, only to find he replaced himself with a robot at the last minute and got away. A legend was on the loose.

It’s more or less impossible to get sales data for comics of that era, but if Iron Man No. 55 sold well, it didn’t do well enough to make Starlin’s job safe. Legendary smart-aleck writer Steve Gerber was assigned to collaborate with him for No. 56 and they concocted a goofy tale about an evil former schoolteacher named Rasputin and a towering beast called Fangor. According to Starlin, Lee found the issue to be wildly off-brand and had him and Gerber removed from the series. But no matter — that same month, January 1973, saw the release of his first issue on the series that would make him famous, the intergalactic superhero saga Captain Marvel. It followed the travails of an alien do-gooder with that moniker and, right off the bat, Starlin and Friedrich — who co-wrote the first four issues, then left Starlin on his own to write and draw — brought Thanos back for a multi-part story line. In its pages, Starlin introduced his creation’s most delicious idiosyncrasy: he seeks to kill in order to woo the femme-bodied physical embodiment of the concept of death. Even in the hoary annals of superhero lore, that was a new one.

Starlin was having a wild time with his fellow Marvel pros. “On a few occasions, there was some imbibement of substance and we would wander around Manhattan in the middle of the night,” he recalls. He and one of his wandering companions, writer Steve Englehart, used the acid-trip visions they had to inform the stories of a character they created, Shang-Chi, Master of Kung-Fu. But the ride was not to last — in 1974, Starlin had the first of his many falling-outs with Marvel. In his telling, the company kept changing up the artists who were assigned to ink his pencils, he got fed up with it, and he and Marvel parted ways one issue before he could resolve his Thanos arc in Captain Marvel.

That first breakup didn’t last long — the EIC lured Starlin back with the offer of working on a character of his choice. He says he could have picked one of the A-list heroes, but opted to go with easily one of the weirdest fellows in the Marvel stable, a synthetic being/Jesus figure known as Adam Warlock. The next great Starlin run began. His time with Warlock was remarkable not only for its grandiose visuals and even more grandiose dialogue (take, for example, this declaration from Thanos, whom Starlin had brought back once again: “You, unlike myself, have chosen the path of the living! You must learn to be one with this life or it will destroy you, Adam! The only way to do this, is to pay its price! It’s price is pain!”). But it was also worthy of note for the fact that Marvel published a Warlock story that was a veiled assault on the company. Entitled “1000 Clowns,” it featured a villain named Lens Tean (an anagram of “Stan Lee”) and a minion named Jan Hatroomi (an anagram of “John Romita,” the name of a leading Marvel artist of the time). Together, they enforce conformity on a multitude of individuals tasked with creating garbage, solely because “that’s the way it’s always been and always will be!”

Astoundingly, the issue didn’t get him fired, perhaps because Warlock was such a smash with fans. Starlin won multiple awards for his work on the title and his stature in the comics landscape grew. However, his relationship with Marvel collapsed once again — in 1976, he says he found his art getting changed (“and changed badly,” he hastens to add) by others after he submitted it, and grew furious. With the publication of Warlock No. 15, Starlin once again walked away … only to return a few months later to work on an Avengers issue starring Thanos.

That’s the general pattern that Starlin and Marvel have followed ever since: Starlin becomes dissatisfied with something, he quits, Marvel approaches him about returning, and he comes back with a new set of cosmic stories — almost always ones that feature Thanos. He quit in 1986 because his paychecks weren’t arriving, then returned in 1989 to write Silver Surfer. He quit in 1994 because he had a bad feeling about the company’s direction (a feeling proven right when the company went bankrupt a few years later), then came back in 2000 to work on a new Captain Marvel series and, eventually, a Thanos solo title. He quit in 2004 because, in his recollection, he was told he couldn’t use Warlock in Thanos and they wouldn’t hire him to work on a Warlock solo series. He returned yet again in 2014 and wrote the first of his recent Thanos graphic novels, The Infinity Revelation, then wrote another one, and was nearly done with a new trilogy of them with penciler Alan Davis when he found out about Cates’s Thanos story and quit. Out of respect for Davis, Starlin finished penning the trilogy, but it will be published with the writing credit of a man who hates the publisher’s guts.

However, in the midst of all this turbulence, great stories have emerged. More than most, Starlin was responsible for expanding Marvel’s consciousness and renewing the company’s cool, especially in the 1970s. The company had already published psychedelia, much of it crafted by Ditko, but Starlin took the trippiness and infused it with moral fervor and epic scope. His space operas could make Star Wars look positively parochial, and he kept up the momentum for decades. Indeed, his most famous tale came nearly 20 years into his time with Marvel, in the pages of 1991’s The Infinity Gauntlet, which saw Thanos assembling the titular object, a glove that he embellished with mystical gems of enormous power. Pencilers George Pérez and Ron Lim brought to life Starlin’s vision of legions of Marvel heroes coming together to take the Mad Titan down during his attempt to wipe out half of all life in the universe — an idea being more or less directly lifted by Marvel Studios for Infinity War.

Starlin says he’s looking forward to that film, and has greatly enjoyed seeing Thanos, Drax, and another creation of his, the Guardian of the Galaxy Gamora, grace the silver screen. Partly, that’s due to the pure excitement of watching his dreams made manifest: of his multiple times seeing that trio of characters in 2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy, he says, “I’d walk out of there with a big grin on my face that would last for days.” It’s also partly due to the fact that the higher-ups have let him meet actors and filmmakers — he got to see some of Infinity War’s shooting and has interacted with Guardians director James Gunn and Gamora actor Zoe Saldana.

But Starlin’s excitement is also tied to the fact that the films are a payday for him. He doesn’t get into details, but says he was able to negotiate an arrangement to get a certain amount of money for non-comics uses of Thanos when Disney bought Marvel in 2009. However, in January 2017, he wrote a Facebook post saying he got paid more for the use of his lesser-known DC character Anatoli Knyazev in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice than he did for all the uses of Thanos in the Marvel movies as of then, combined. According to Starlin, that led Disney to renegotiate the agreement, which he now calls “a fairly fair deal.”

That said, he’s happy to collect his movie bucks and pass on actually making comics for Marvel, now that the comics mavens have ticked him off again. He’s still working: he just wrote a story called “Berserker,” drawn by Phil Hester, for Aftershock’s anthology book Shock; he also has a long bibliography of prose novels and is continuing to write them, with a loose adaptation of his DC comic-book series Hardcore Station currently in the hopper. And he leaves behind a legacy beyond Marvel, having created famed stories ranging from the death of Batman sidekick Jason Todd for DC in 1989 to a long-running creator-owned saga about an interstellar adventurer named Vanth Dreadstar. Whether or not he ever works on another Marvel story, his legacy is secure.

When I ask Starlin what the nature of his tumultuous relationship with Marvel is, he pauses for a second, then replies, “It’s been Thanos.” He can’t escape his fascination with the character, nor can he escape his anger when he feels his Thanos stories are being undermined or meddled with. “I would never do half the terrible things that he does, but at the same time, I’m amused by his straightforwardness and his complete lack of morality,” Starlin says. “He does have his more human moments along the way, but basically, he’s a black hole of monstrousness.” On the whole, he remains happy with what he’s been able to pull off with him, even if it meant lots of back-and-forth with the people who own the bad guy. “You usually have three to four careers in a normal human lifespan, these days,” Starlin says. “Mine just happen to be in the same career.”