The origin story of comic books isn’t flashy. No radioactive spider bite, atomic explosion, or shadowy experiment granted the medium the sort of ability that would have allowed it to arrive on early-20th-century drugstore racks as glossy, fully formed vehicles for sophisticated entertainment. Rather, it took a steady progression over the course of more than 75 years for the form to fully understand, and then harness, its powers. When the first comics arrived on newsstands in the early 1930s, they were a cynical attempt to put old wine in new bottles by reprinting popular newspaper comic strips. Cheaply printed and barely edited, those pamphlets were not what a critic at the time would have called high art.

Yet today, the medium is flourishing in ways its ancestors could never have imagined. From floppy single issues of superhero sagas to hefty graphic novels, harrowing comic-book memoirs to YA fare about queer adventurers, readers can tap into a dizzying array of what the great cartoonist Will Eisner famously termed “sequential art.” And, as evidenced by the sheer number of adaptations in film, television, and even on the Broadway stage, the rest of the entertainment industry has grown wise to what fans have long known: There’s a special alchemy that comes when you tell a story with pictures.

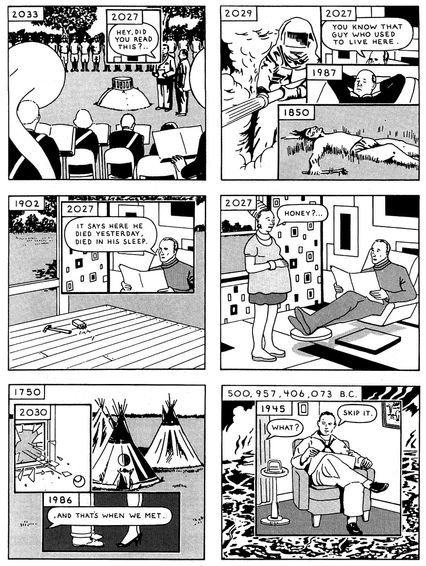

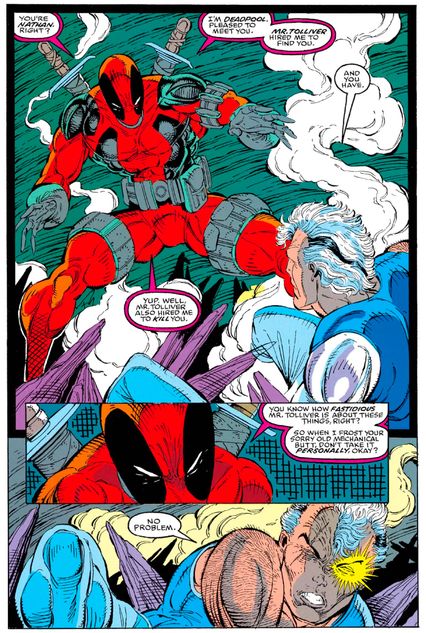

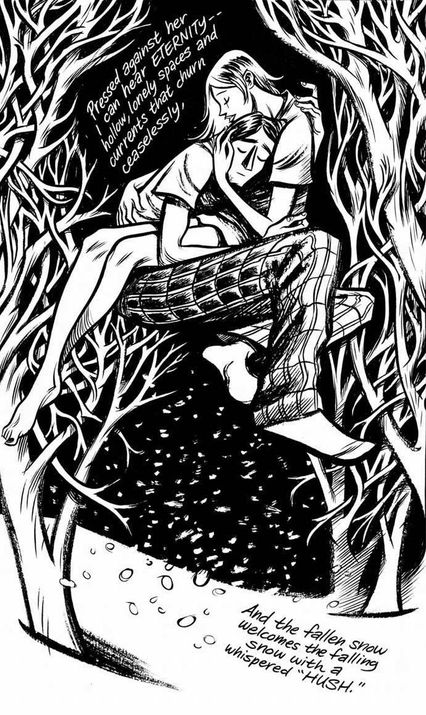

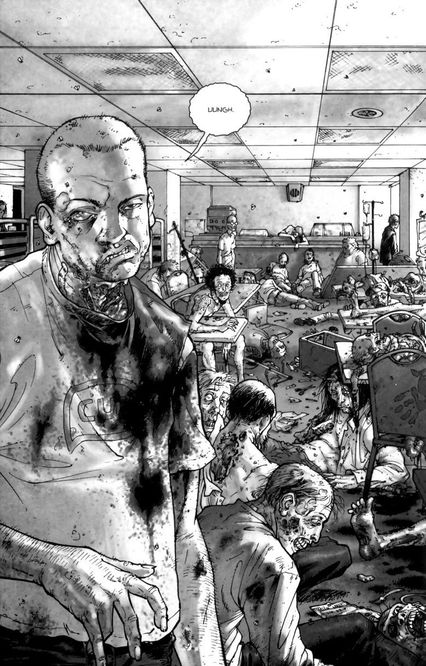

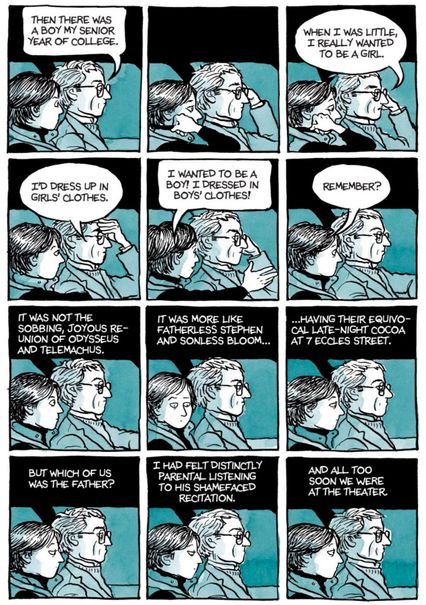

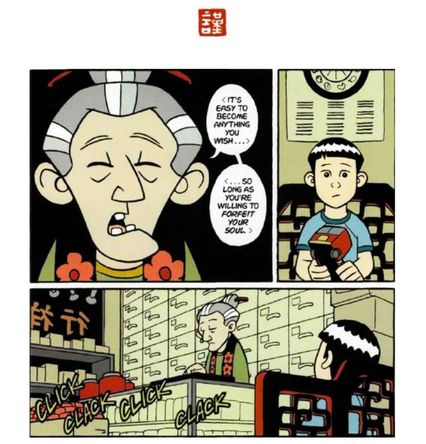

Printed images — and the comic book medium’s unique presentation of them — are at the heart of this feature. We have set out to trace the evolution of American comics by looking at 100 pages that altered the course of the field’s history. We chose to focus on individual pages rather than complete works, single panels, or specific narrative moments because the page is the fundamental unit of a comic book. It is where multiple images can allow your eye to play around in time and space simultaneously, or where a single, full-page image can instantly sear itself into your brain. If there are words, they become elements of the image itself, thanks to the carefully chosen economy of the writer and the thoughtful graphic design of the letterer. In the best pages, one is torn between staring endlessly at what’s in front of you or excitedly turning to the next one to see where the story is going. When comics have moved in new directions, the pivot points come in a page.

To assemble our list of 100, we assembled a brain trust of comics professionals, critics, historians, and journalists. Our criteria were as follows: A page had to have either changed the way creators approach making comics, or it had to expertly distill a change that had just begun. In some cases, there were multiple pages that could be used to represent a particular innovation; we’ve noted those instances. We didn’t necessarily pick the 100 best pages — there are many amazing specimens we didn’t include because they didn’t have a significant influence on the craft of comics. These are also not the only 100 pages that have shaped comic books, but each, in its own way, has had a profound impact on the form as we know it. And, this being comics, we had to get a little nitpicky: We’re only dealing with comics first published by North American publishing houses, and we’re not including newspaper comic strips, webcomics, or reprints thereof.

Some pages are notable for their written content — game-changing first appearances, brilliant narrative innovations, and so on. Some are significant because the artwork told a story in ways no one had thought to do before, and ended up being emulated — or, in some cases, outright aped. All are interesting on their own and integral parts of the tomes from which they were plucked. We conclude on what we think is a high note, with a few recent comics that have already made an impact and portend a richer and more diverse future. Strung together, these pages are a megacomic of their own, documenting the evolution of an art form in constant flux.

You can click on the title of each page to open a window with a full-sized version.

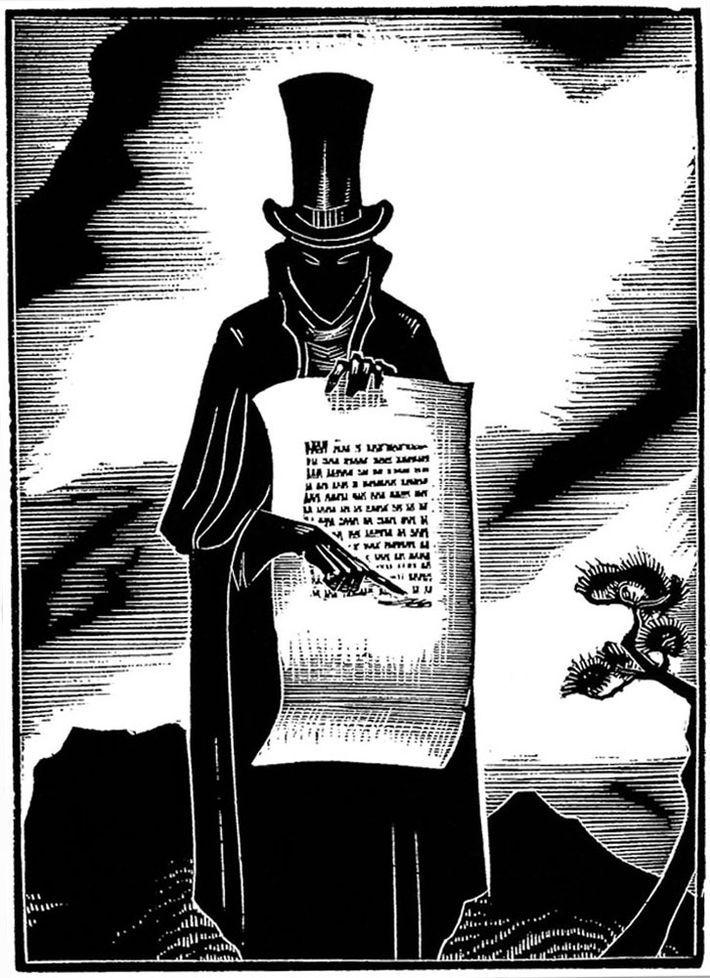

Gods’ Man (1929)

Writer, penciler, and inker: Lynd Ward

We could “Um, actually” our way through candidates for “First Comic Book Ever” until we’re blue in the face. But it’s inarguable that one of the leading pioneers of modern longform graphic storytelling was Flemish illustrator Frans Masereel. Right after World War I, he created a series of “pictorial narratives” without words — you may have spotted his most famous, Passionate Journey (1919), in the gift shop at your local art museum.

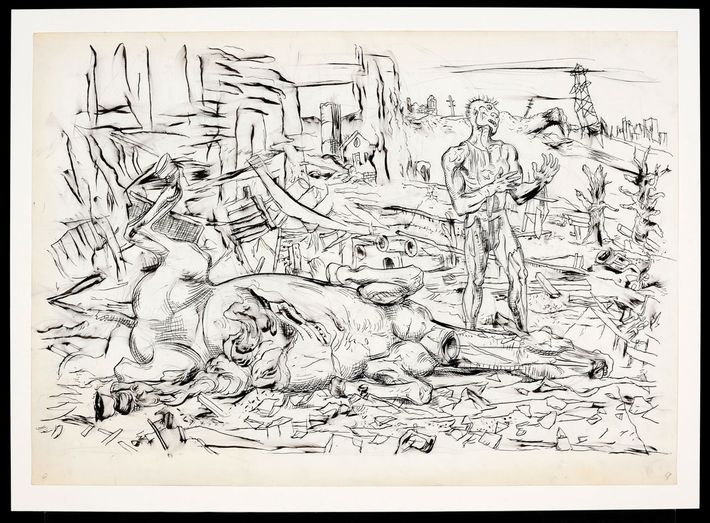

Chicago-born art student Lynd Ward discovered Masereel’s work while studying printmaking in Leipzig, Germany, and was inspired to use the oldest print medium — woodblocks pressed into ink — to create something very modern: the first stand-alone graphic narrative by an American, or as he called it, a “novel in woodcuts.” Gods’ Man (1929) tells the story of a struggling artist who makes a supernatural bargain with a mysterious stranger (pictured here) for a magic brush that comes at a terrible cost. The book, composed of one woodcut illustration on each of the volume’s 139 pages, was a surprise success, and Ward produced five more graphic novels (though use of that term was decades away) before settling into a career as an illustrator and fine artist. His work was a huge inspiration to future cartoonists, including Art Spiegelman, whose Maus was heavily influenced by Ward’s woodcut style. Spiegelman later edited Library of America’s excellent boxed set of Ward’s silent novels.

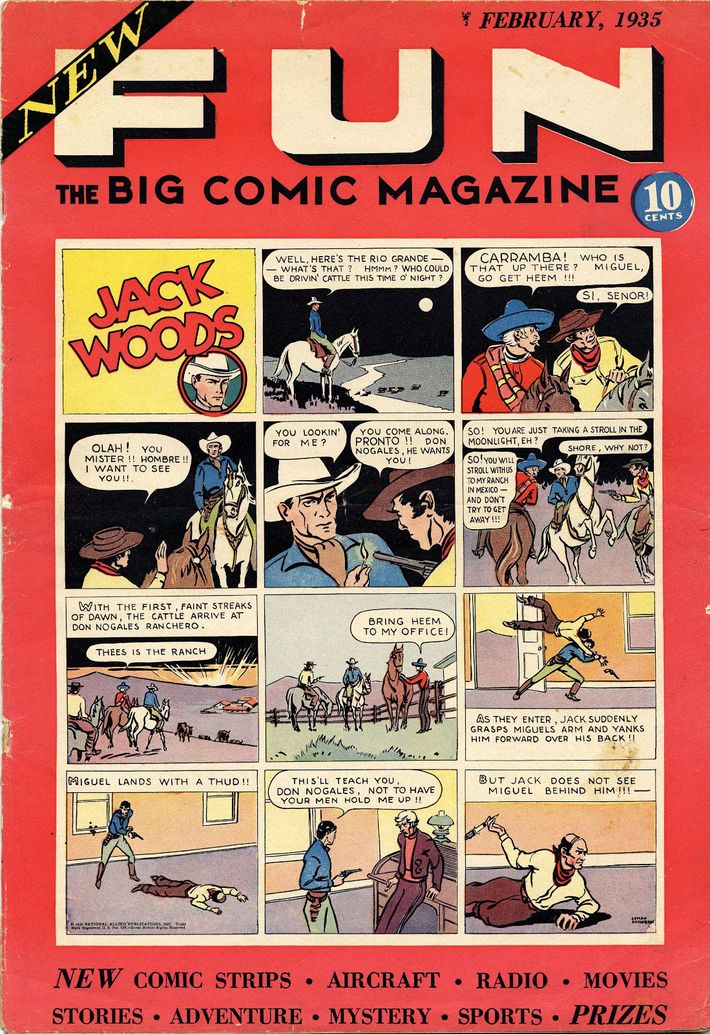

New Fun: The Big Comic Magazine No. 1 (1934)

Writer: Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson; Penciler and inker: Lyman Anderson

If Lynd Ward pioneered the American graphic novel, it was left to more commercially minded creators to concoct the floppy, staple-bound items that would become known as “comic books.” They began as an offshoot of the comic-strip boom in the late 1920s/early 1930s, when the comics section in newspapers (dubbed the “funny pages”) increased in size as adventure-themed strips grew to match the popularity of their sillier comedic counterparts. Eventually, Eastern Color, a successful comic-strip printer, realized that the popularity of comic strips could be used to attract customers. They struck up a deal with the Gulf Oil Company to produce a small “book” of four full-page strips that would be given away as a promotional item at Gulf gas stations. Gulf Oil Weekly proved to be popular, inspiring Eastern Color and Dell Publishing to try selling “books” of reprinted comic strips. After a few attempts, Dell backed out of the project. Eastern Color went on alone and launched the ongoing series, Famous Funnies, in May 1934.

Following the success of Famous Funnies, pulp magazine writer Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson founded National Allied Publications and released New Fun Comics No. 1 in January 1935. The major distinction of New Fun Comics was that, right from the first story of cowboy Jack Woods (which appeared on the cover — an approach largely eschewed by future comics), these comics were entirely original material rather than reprinted comic strips. (Famous Funnies had the occasional original material, but it was rare and typically used as filler.) With its declaration that these flimsy products could provide exciting, new content, New Fun No. 1 was the birth of the comic book as we now know it.

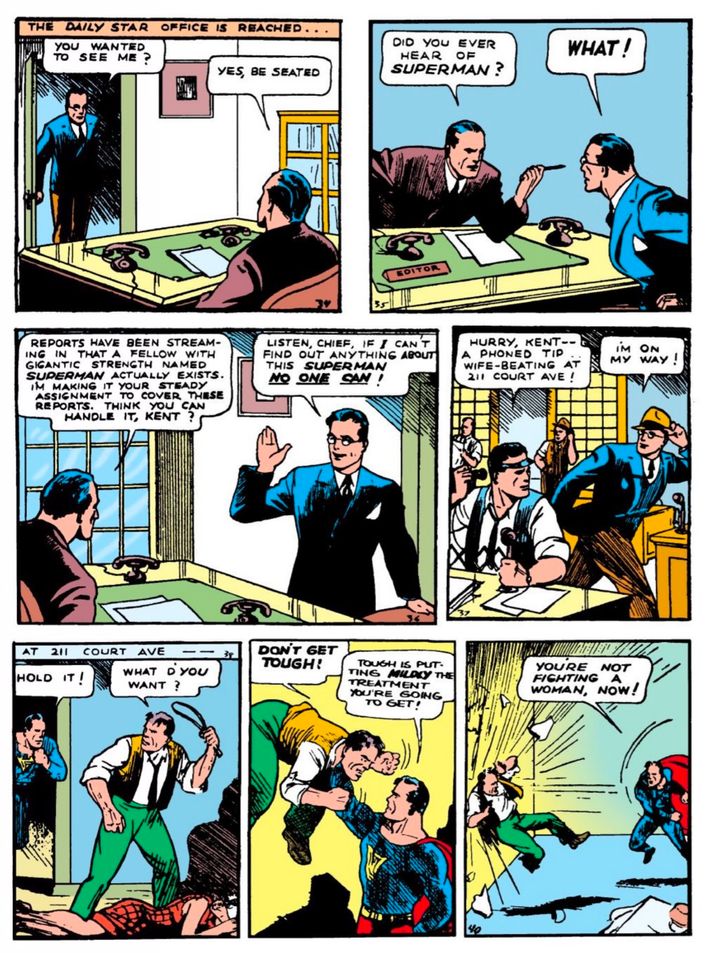

Action Comics No. 1 (1938)

Penciler, inker, and letterer: Joe Shuster; Writer: Jerry Siegel

In which we learn that superheroes were social-justice warriors from the start. Steeped in the politics of the left-leaning, working-class Depression milieu from which Superman emerged, the man of steel’s first appearance shows him foiling a lynching, roughing up war profiteers, breaking a wrongly convicted murderer out of death row, and beating his ideals into this domestic abuser. The first true superhero was forged in the crucible of progressive social politics.

Creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster originally conceived “Superman” as a newspaper strip, which is obvious from the arrangement of this page, with a “button,” or mini-cliff-hanger, in the last panel of each tier. It was only after being rejected from every newspaper syndicate they could find that Siegel and Shuster reluctantly agreed to let fledgling publisher National (later renamed “DC,” after another of their series, Detective Comics) run it as the cover feature of their new title, Action Comics. Shuster cut up his comic strips and pasted the panels onto a board in the new comic book format.

National changed ownership between Action Comics accepting Siegel and Shuster’s story and actually publishing it. Ironically, the new brass thought the debut issue’s now-iconic cover — Superman smashing a mobster’s car into a mountain — was so stupid they forbade Supes from appearing on any future fronts. Those National execs changed their minds, though, once sales kept rising, and they learned that kids weren’t going to the newsstand asking for Action Comics — they were looking for Superman. It was the start of not just a genre, but an entire industry.

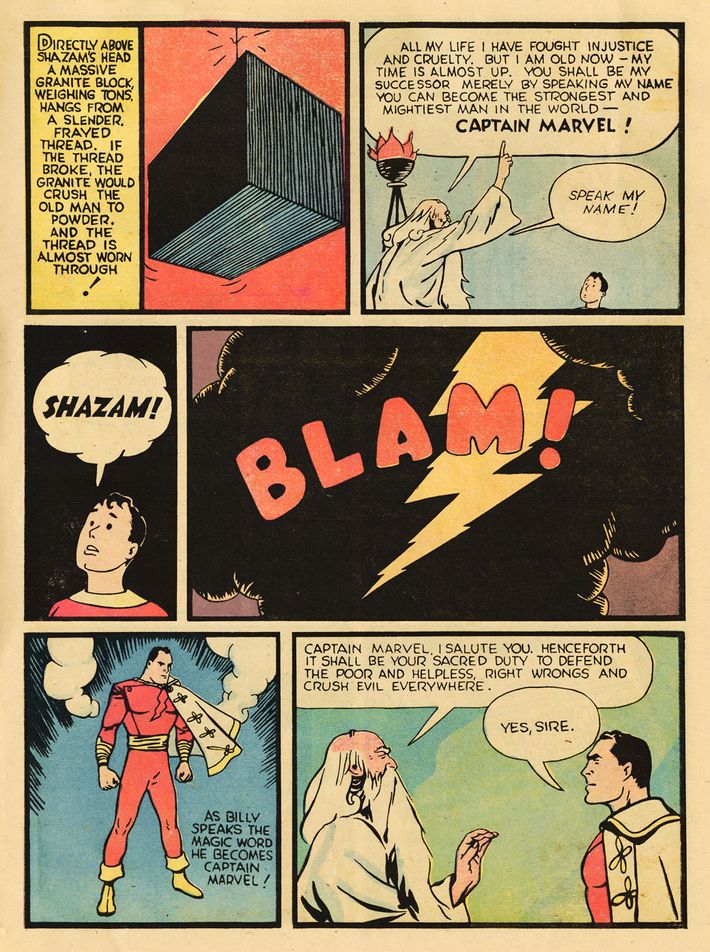

Whiz Comics No. 2 (1939)

Writer and colorist: Bill Parker; Penciler and inker: C.C. Beck

By the end of 1938, it was clear that National’s “Superman” feature was a tremendous success. It had been out for barely a year since the release of Action Comics No. 1 when publisher Fawcett Publications got into the superhero game by introducing Captain Marvel in Whiz Comics No. 2. The intention of Captain Marvel was to create Fawcett’s own Superman — except with his secret identity being a 12-year-old boy, Billy Batson, who transforms into hero form when he exclaims “Shazam!” (The name stands for the initials of the magical beings who supplied his powers: the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, etc.)

The blend of Superman-style adventures with the wish fulfillment of a kid led to Captain Marvel becoming the most popular superhero of the 1940s, selling better than even his Kryptonian inspiration and leading to an array of Marvel-themed spinoffs such as Mary Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr. Naturally, National sued Fawcett, and the case went on for years until National seemingly won in 1952. Rather than appeal further, Fawcett just stopped publishing superhero comics (sales had already been declining), and eventually sold Captain Marvel to National. (He remains a DC property to this day, with a feature film on the way next year.) The notion of giving kids a character they could identify with proved to be massively influential.

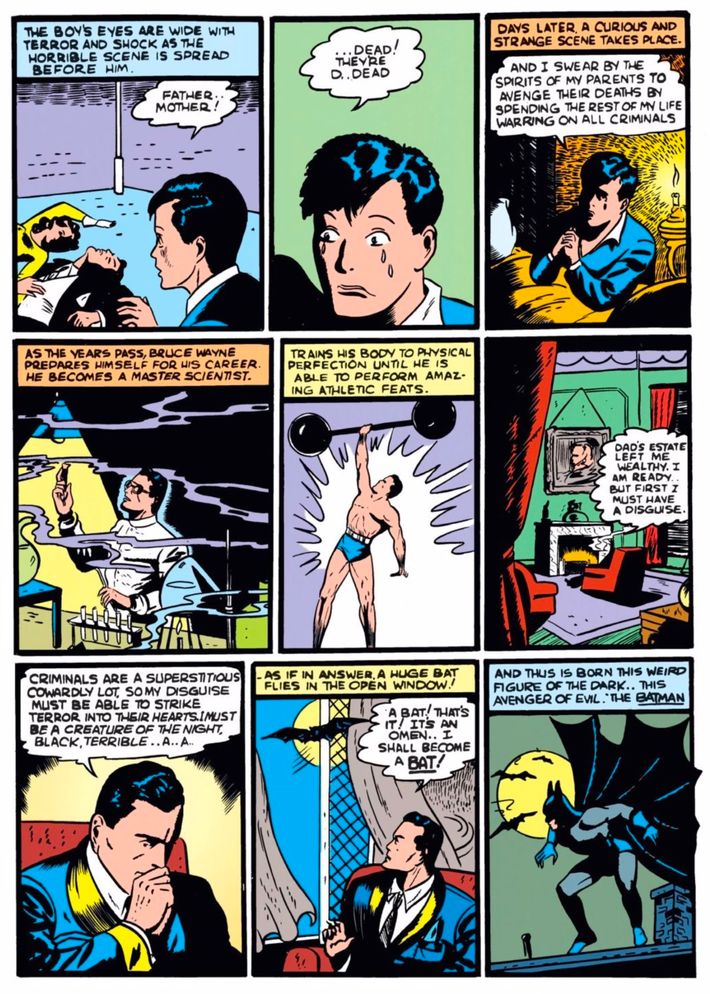

Detective Comics No. 33 (1939)

Writer: Bill Finger and Gardner Fox; Pencilers: Bob Kane and Sheldon Moldoff; Inker: Kane; Letterer: Moldoff

National quickly looked to expand their burgeoning superhero empire. Every freelancer knew that National was looking for new superheroes. It was with this in mind that writer/artist Bob Kane, who had done a few different features for National before finally landing a regular feature with the adventure serial, “Rusty and His Pals,” sat down to create his own superhero, whom he called the Batman. The problem for Kane was that his ideas for the character were not particularly strong and he knew it. So he enlisted writer Bill Finger, whom Kane had recently hired to write “Rusty” for him, to develop the character. Finger changed nearly everything about the character but his name and their revamped Batman (who was heavily influenced by pulp hero the Shadow) made his debut in 1939’s Detective Comics No. 27, drawn by Kane and written by Finger (Finger lifted the plot of the Shadow novel Partners of Peril for that first Batman story).

Finger teamed up with Kane for one of the most important Batman stories ever, the origin of the character in Detective Comics No. 33. At this point in comic-book history, most superheroes had no underlying motivation for being heroes other than a desire to do good. With Batman’s origin, Kane and Finger introduced the novel idea of a young boy witnessing his parents’ murders and being driven to avenge their deaths by becoming a superhero. It was the building block of Batman’s characterization for years to come and inspired countless angsty superheroes with similar sob stories.

Marvel Mystery Comics No. 8 (1940)

Writer, penciler, inker, and letterer: Bill Everett

One early company that tried to cash in on the superhero craze was Centaur Publications, a pulp publisher that had recently purchased two failed comic-book companies, Comic Magazine Company and Ultem Publications. Centaur’s superhero features, like “Amazing Man” and “The Arrow,” did not exactly set the world afire. Centaur’s art director was Lloyd Jacquet, who had helped put together the first issues of New Fun Comics for National in 1934. Jacquet saw that demand for new superhero content was so great that he left Centaur to form the comic-book packager Funnies Inc., in the process bringing along a number of Centaur artists.

Funnies Inc. was hired by publisher Martin Goodman to put together a trial comic. The issue, Marvel Comics No. 1, included a Bill Everett short story introducing the roguish Namor the Sub-Mariner, and a Carl Burgos story introducing a heroic android called the Human Torch. (He was unrelated to the later Fantastic Four character of the same name.) The issue sold so well that Goodman hired away some Funnies Inc. creators to work directly for him at his new company, Timely Comics. The comic book was retitled Marvel Mystery Comics and history was made in the eighth issue when Everett and Burgos (good friends from their time together at Centaur) had each other’s characters appear in their two features, with Human Torch hunting down Namor. It was the first superhero crossover and introduced the idea of a shared comic-book universe, concepts that became key parts of superhero-comics history.

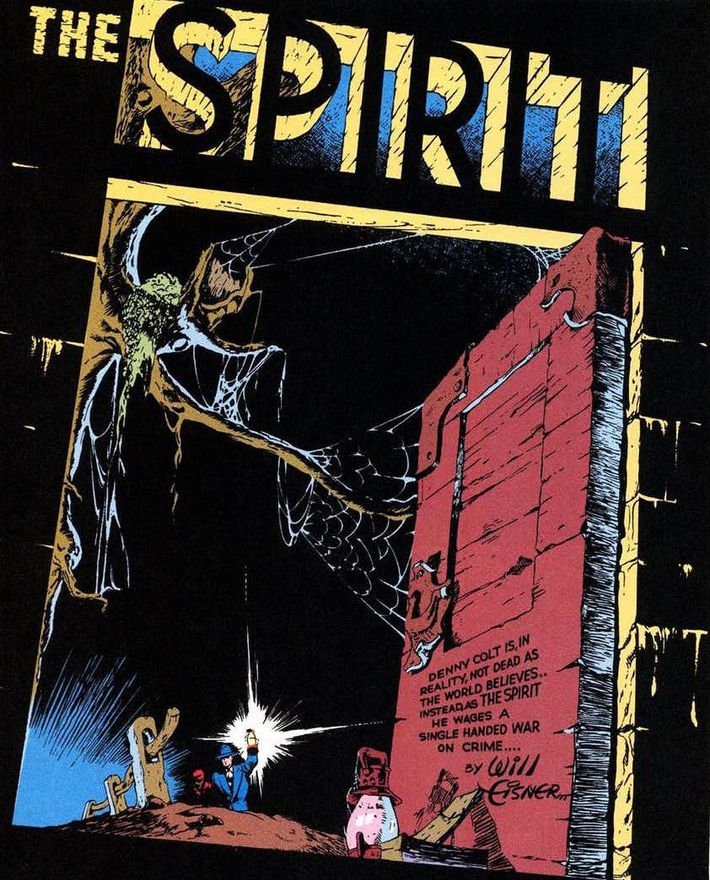

The Spirit, December 8, 1940 (1940)

Writer, penciler, and inker: Will Eisner; Colorist: Joe Kubert; Letterer: Sam Rosen

The most successful of the fevered content-generating stables known as comic-book packagers in the late 1930s was Will Eisner and Jerry Iger’s studio. They had formed their company in 1936, so they were well positioned when the superhero boom following Action Comics No. 1 came about. By the end of 1939, they had 15 writers and artists working for them, but Eisner himself remained their greatest asset. He was a brilliant writer and artist, able to produce comic-book features in a variety of formats. Eisner and Iger were making a great deal of money in the late 1930s. However, Eisner wanted more from his career.

He came up with the idea of doing a comic-book series that would be appear as a supplement to the weekly Sunday color comic-strip pages in local newspapers. He wanted to own this idea outright, so he sold his interest in their packaging studio to Iger in exchange for Iger not contesting Eisner’s ownership of this new enterprise. The supplement would open with a story starring the Spirit, a new costumed detective character Eisner created, with backup stories featuring other Eisner creations. When it launched on June 2, 1940, the series looked like most other Sunday comic strips. Eventually, once the series was clearly a success, Eisner began to experiment. First, he did splash pages like most other comic books of the period (three-quarters of the page given to one image and then one-quarter showing the first panel of the story) but December 8, 1940, was the first time Eisner worked the name of the feature into the landscape of the drawing. Soon, The Spirit would be most known for the way that the title was brilliantly worked into the opening splash page. Eisner’s Spirit was a direct influence on the many acclaimed artists who worked as assistants for him while he did The Spirit (and continued the series while he was drafted during World War II), like Jules Feiffer, Jack Cole, Wallace Wood, and Jerry Grandenetti. What’s more, Eisner’s experimental artwork was a clear influence on artists like Jack Kirby and Jim Steranko, the latter of which directly homaged Eisner in a number of his works.

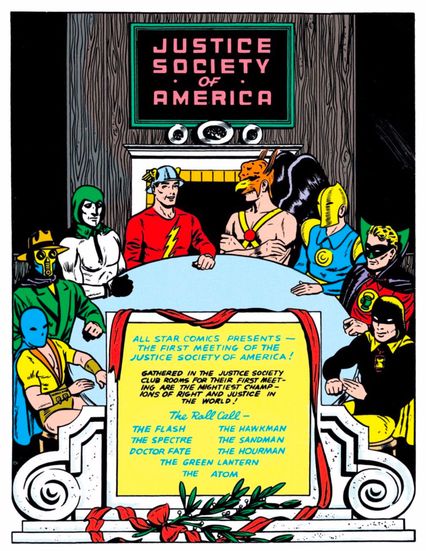

All-Star Comics No. 3 (1940)

Writer: Gardner Fox; Penciler and inker: Everett E. Hibbard

One of the earliest comic-book pioneers was Max Gaines, the salesperson for Eastern Color Printing who first devised the idea of creating “books” collecting color comic strips to be used as promotional items for companies. He was the mind behind Eastern Color’s Famous Funnies series and soon was interested in setting up his own comic-book company. Harry Donenfeld, the co-head of National Allied Publications, agreed to help fund Gaines’s new venture, which was called All-American Publications, provided that Gaines took on Donenfeld’s National Allied partner, Jack Liebowitz, as a partner (partially to keep an eye on Gaines and partially to keep Liebowitz from leaving and forming his own company). Along with Detective Comics (a small company formed solely for the publication of the aforementioned Detective Comics), All-American and National Allied all used “Superman-DC” as their shared name on the covers of their titles.

In 1940, All-American launched a comic-book series called All Star Comics, which would feature short stories starring heroes from both All-American and National Allied. With the third issue, however, they tried something novel. Writer Gardner Fox wrote a framing sequence that connected the disparate stories in the issue. Said framing sequence revealed that all of the various heroes in the book were actually part of a single superhero team known as the Justice Society of America. For years, the Justice Society parts of the book only worked as a framing sequence to set up the solo stories, but eventually the book began telling full-length Justice Society stories. Since All-American was technically its own company (Gaines would sell his interest in the company to National Allied in 1944 and then form EC Comics), this was not only the first superhero team but also the first intercompany crossover, two ideas that have subsequently been used to death and beyond.

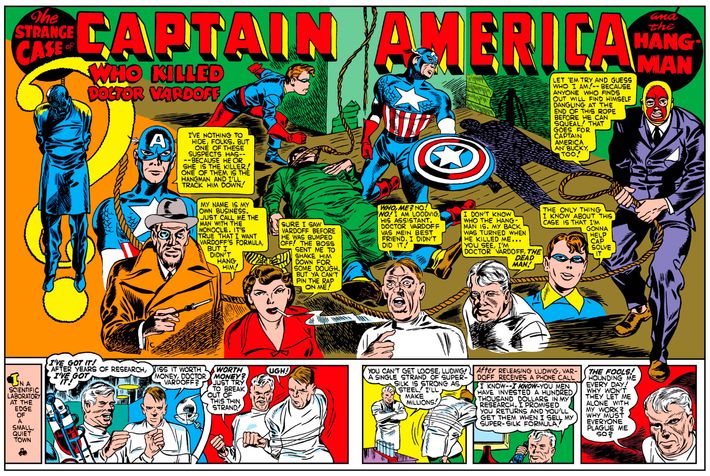

Captain America Comics No. 6 (1941)

Writers: Joe Simon, Jack Kirby, and Stan Lee; Pencilers: Charles Nicholas Wojtkoski, Al Avison, Jack Kirby, Joe Simon

Joe Simon and Jack Kirby were into punching Nazis before it was cool, as can be seen from the famous cover to their Captain America Comics No. 1, in which the titular super-soldier blitzkriegs der Führer in the face almost a full year before the attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II. The duo was equally as innovative between the covers, becoming the Golden Age’s unquestioned masters of superhero art (just as Kirby as a solo act would become the Silver Age’s unquestioned master). Simon and Kirby would have characters’ fists and legs break the panel borders, as if heroes and villains were so excited to beat each other up they were almost literally leaping off the page.

But they became best known for their spectacular double-page spreads, which, if they did not invent, they certainly perfected, beginning with this tale in Captain America Comics No. 6. This “widescreen” technique of spreading a single image across two whole pages starts the story with a bang and immediately draws the reader in with bombastic action and/or an opening “teaser,” like you see here. Two-page spreads are now not only commonplace, but de rigueur.

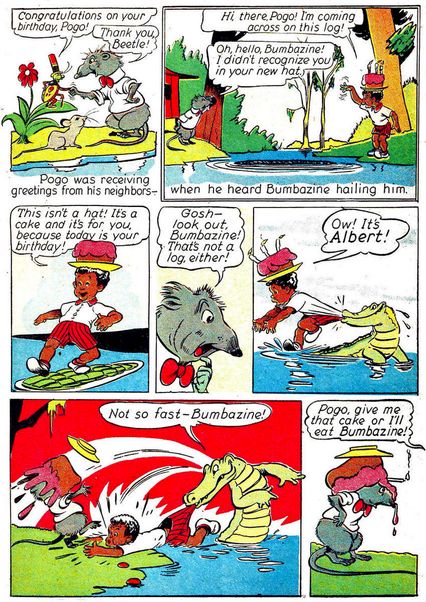

Animal Comics No. 1 (1942)

Writer, penciler, and inker: Walt Kelly

Dell Publishing began Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories in 1940 and, owing to the popularity of its subject matter, it became one of the best-selling comics series of all time in the United States, with a monthly circulation of well over 3 million copies. After all, Disney comics spawned whole countries’ industries around the world: In France, the first true comic book was 1934’s Le Journal de Mickey, beginning, as WDCS did, as a reprint of the “Mickey Mouse” comic strips. In Japan, Osamu Tezuka single-handedly launched manga with his Disney-influenced style in 1947’s New Treasure Island.

Speaking of international influence, the first “original” (non-reprint) story in WDCS wouldn’t come until 1942’s adaptation of “The Flying Gauchito,” a segment in the film The Three Caballeros. The artist on “The Flying Gauchito” comic was a former Disney animator named Walt Kelly. Kelly would create Pogo the Possum for Animal Comics later that year, another Dell-published Disney-style comic. This page is from that first story, “Albert Takes the Cake,” with a much more zoologically accurate Pogo and Albert the Alligator. Kelly and Pogo would enjoy even greater success in newspaper funnies pages, the rare instance of a comic-book character that became more popular in comic-strip form.

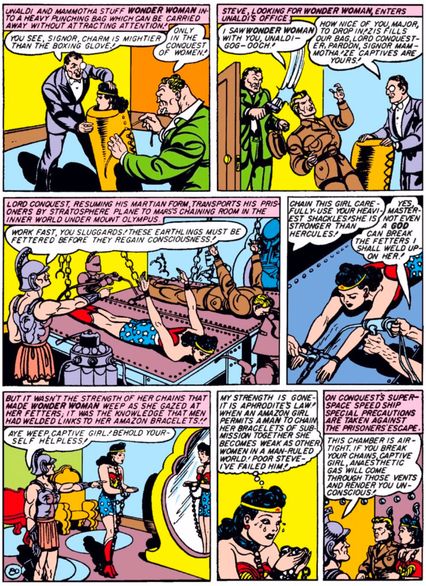

Wonder Woman No. 2 (1942)

Writer: William Moulton Marston [as Charles Moulton]; Penciler and inker: Harry Peter (as H.G. Peter)

“Tell me anybody’s preference in story strips, and I’ll tell you his subconscious desires,” said Dr. William Moulton Marston, co-creator of Wonder Woman. Huh. You don’t say, Doc? A psychologist and contributor to the invention of the lie detector, Marston was, to put it mildly, an interesting individual. After denouncing superhero comics for their “blood-curdling masculinity,” he was invited by All-American Comics to put his money where his mouth was by creating a strip more to his liking. This was the result: Wonder Woman, written by Marston under a pseudonym and drawn by veteran illustrator Harry Peter.

A cornerstone of Marston’s belief system was women’s inherent superiority to men, which may explain why he liked to see them get tied up so much. Here we have no less than three forms of bondage on one page: wrist and ankle shackles, chained to the wall by the neck, and, most imaginatively, getting sewn up inside a punching bag. Lest you think we picked this page for pure sensationalism, rest assured that this was a pretty typical early Wonder Woman adventure. One later Marston tale had no less than 75 bondage panels in it.

After Marston died of cancer in 1947, the creators who inherited Wonder Woman would scrub out all the kink. But the proto-feminism of those early days — here embodied in the next-to-last panel where Diana chastises herself for submitting to a man’s will — would live on in the now-legendary character and the many superheroes that imitated her.

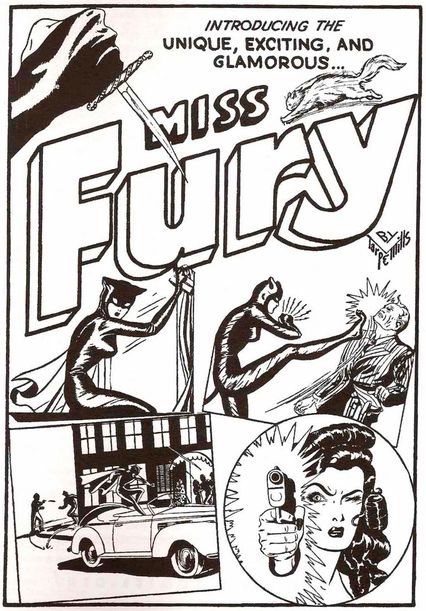

“Miss Fury” No. 1 (1942)

Writer, penciler, and inker: Tarpé Mills

It all started because fashion illustrator and cartoonist June Mills broke her foot. While laid up, Mills doodled out ideas for an adventure comic strip with a heroine modeled on herself, who had a cat sidekick very much like her own pet Peri Purr. “Black Fury” debuted in the newspaper funnies pages on April 6, 1941, becoming the first female comics hero created by a woman and predating Wonder Woman’s (man-created) first appearance by several months. Our hero, Marla Drake, is a socialite turned nocturnal ass-kicker when she apprehends a gangster while en route to a costume party. Conveniently, she’s dressed in a catsuit that has since been ripped off by innumerable heroines and villainesses.

Worried that male readers would reject such a rock-em, sock-em action strip if they knew it was created by a woman, Mills hid her gender by using her middle name, Tarpé, as a pseudonym. She was outed soon enough, though, and it didn’t hurt the strip’s popularity one bit: It was even renamed “Miss Fury,” feminizing it even further. The page you see here is the introduction to Miss Fury’s comics series, which was a big hit for Timely — later known as Marvel — featuring new material and reprints. Mills brought her fashion skills to bear in dressing Drake and her femme fatale foes in the latest styles, a practice adopted by later teen comics, and Miss Fury herself received one of the highest accolades a ‘40s comics character could receive: she adorned the nose of many a WWII bomber.

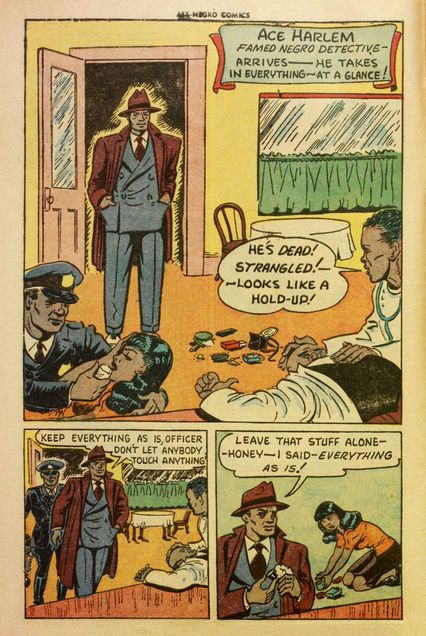

All-Negro Comics No. 1 (1947)

Writer, penciler, and inker: John Terrell

While the 1940s might have been the “Golden Age” in a number of readers’ views, it certainly was not a golden age in how comic books depicted African-Americans. Characters like the Spirit’s sidekick Ebony White and the Young Allies member Whitewash Jones were straight out of minstrel shows, with grotesquely large lips and other exaggerated features. This was the sort of thing that was on Orrin C. Evans’s mind when he lost his job in 1947. Evans had been working at the Philadelphia Record since the early 1930s, where he had made history by becoming the first African-American reporter to be on staff as a general reporter at a mainstream white-run newspaper. The outlet went out of business in 1947, following a strike, so Evans teamed up with a few of his Record co-workers to address what he felt was missing in the comic-book world: strong, positive depictions of African-Americans.

In June 1947, they launched All-Negro Comics No. 1, the first comic-book series written and drawn entirely by African-American creators. While each of the artists likely wrote their own strips, Evans oversaw the whole endeavor and made sure that all of the heroes be depicted non-stereotypically. Evans’ brother, George, drew the heroic Lion-Man, while John Terrell wrote the lead feature in the series, the stalwart African-American police detective, Ace Harlem. Sadly, when Evans went to produce a second issue, the company that sold him the paper for the first issue was no longer willing to sell to him — nor would any other paper company. He spent the rest of his life working in journalism. Nevertheless, All-Negro Comics tales like this one about Ace Harlem must be acknowledged as forerunners of black heroes like Black Panther and Luke Cage.

Young Romance No. 1 (1947)

Penciler: Jack Kirby; Inker: Joe Simon

Today, Jack Kirby is known best as a superhero artist. Yet the most lucrative genre of Kirby’s career, from the late ‘40s through the mid-’50s, was romance. It gave Kirby and his business partner Joe Simon a life raft at a moment when superheroes were languishing and everything was up for grabs — a moment when comic-book sales were soaring but books about costumed derring-do were old hat. Romance comics, introduced by Simon and Kirby with this story in 1947, became more than a genre — they were a sensation. By the end of the ‘40s, romance grew to a reported one-quarter of the comic-book market. Romance enabled Simon and Kirby to buy houses in the suburbs, and for a decade kept Kirby busier than all the other genres he worked in combined. These comics, modeled on women’s true-confession pulps, offered something vital, and were part of a generation of comic books trying to age up and diversify their audience.

“Pick-Up” distills the genre’s conventions: confessional first-person narration, regrets for sinful recklessness that expose the narrator to risk and shame, and an opening splash that mixes moralism and prurience. The story is punchy and exhilarating. (Simon and Kirby so liked the protagonist that they brought her back for a sequel in issue No. 11.) Though endlessly mocked (see the arch Pop Art paintings by Roy Lichtenstein and other spoofs), the best of the romance comics, like Young Romance No. 1, dealt with not only ripe sensuality and thwarted desire but also issues of prejudice, class shame, and social identity, heightened and compressed into brief morality plays.

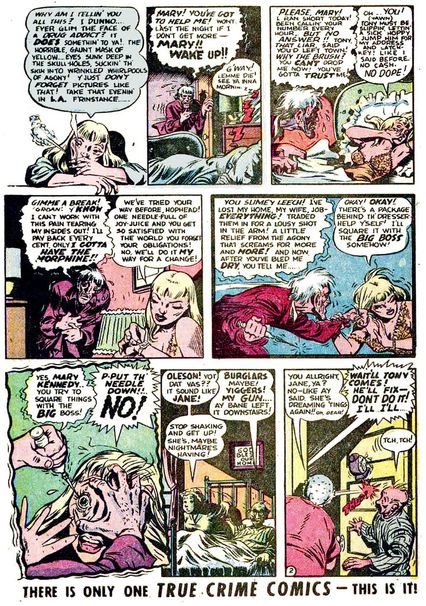

True Crime Comics No. 2 (1948)

Writer, penciler, and inker: Jack Cole

There is no darker chapter in comic-book history than the anti-comics craze kicked off by Seduction of the Innocent. It was a 1954 best seller written by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, who argued that the (admittedly lurid) crime comics clogging the newsstands of America were the direct cause of a spike in juvenile crime. The book reprinted countless panels of mayhem and extremely male-gaze-y women. But nothing was more disturbing than a panel from this page of the story “Murder, Morphine and Me!” in which a woman is about to have a needle stuck in her eye by a crazed junkie. The injury-to-the-eye motif was one of the most harmful aspects of comics, Wertham wrote: “This detail … shows perhaps the true color of crime comics better than anything else. It has no counterpart in any other literature of the world, for children or adults.”

That last claim is a good example of Wertham’s shaky research (what about Un Chien Andalou? Or Oedipus Rex?) but fake news was as popular in 1954 as it is now. “Murder, Morphine and Me!” was by Jack Cole, best known for creating the goofy, lovable Plastic Man, but this time he created a daring, fever-dream melodrama. A teenage Art Spiegelman would discover the panel in a New York City library and fall in love with Cole’s work, but the wider damage was already done: Wertham was so persuasive that Senate hearings were held to determine if comics were merely evil or outright enemies of the state. Dozens of publishers went out of business and the onerous Comics Code was established. Cole, after becoming one of the original Playboy cartoonists, committed suicide in 1958, and he left a legacy of dynamic pencils and layouts that could delight as well as terrify.

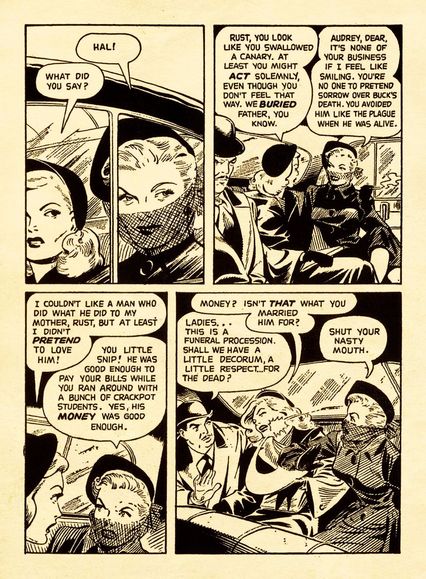

It Rhymes With Lust (1950)

Writers: Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller (as Drake Waller); Penciler: Matt Baker; Inker: Ray Osrin

Arnold Drake is best known for co-creating the original Guardians of the Galaxy for Marvel and Doom Patrol and Deadman for DC, but in 1949 he was going to college thanks to the GI Bill and picking up extra cash writing comics scripts. It hadn’t been lost on him that comic books were his fellow soldiers’ favorite reading material overseas, and he hit on the idea of appealing to college-bound veterans like himself with more sophisticated fare — longer, more serious stories, aimed at adults. Basically, he had come up with the graphic novel as we know it today.

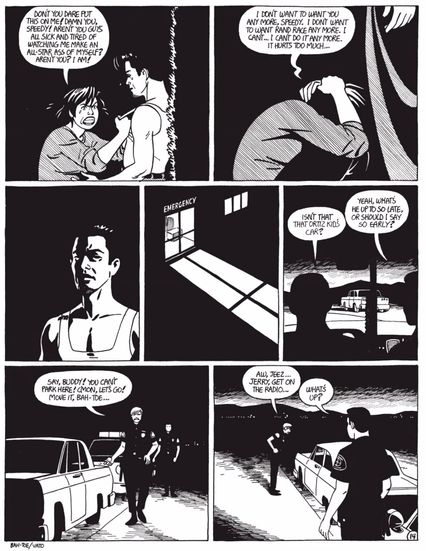

It Rhymes With Lust, co-written with Drake’s friend Leslie Waller, is a long romance comic, revolving around redheaded man-eater Rust Masson (whose first name rhymes with … see, now you get it). Rust masterminds Dallas-style shenanigans in fictitious Copper City, playing her myriad rivals and pawns off of each other and slapping around her goody-two-shoes stepdaughter. Three decades ahead of its time, this “picture novel” didn’t sell well enough to spawn many imitators, but nonetheless remains a significant milestone in American comics history.

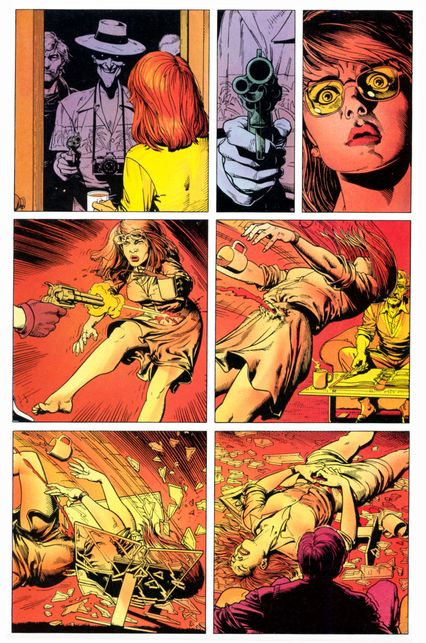

Also noteworthy is the fact that this first graphic novel was drawn by Matt Baker, among the greatest of the Golden Age’s African-American artists. A sharp dresser — here he is with Lust publisher Archer St. John — and believed to be gay or bisexual, Baker was best known for depicting elegant, beautiful women, a skill on display here and in the title he was most associated with, Phantom Lady (antecedent of Watchmen’s Silk Spectre). A heart attack killed Baker when he was just 37, so who knows how far his star could have risen; but it’s important to recognize that creators of color and LGBTQ creators have been with comics since the earliest days.

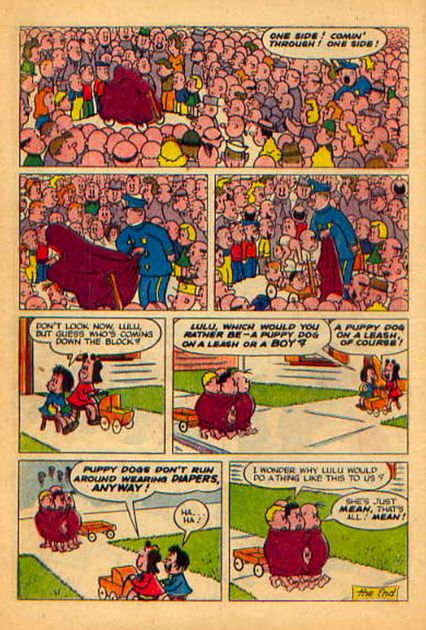

“Marge’s Little Lulu” No. 38 (1951)

Writer: John Stanley; Pencilers: John Stanley and Irving Tripp; Inker: Tripp

It’s hard to pick just one page to represent John Stanley’s oft-reprinted story “Five Little Babies,” starring a character ported over into comics from The Saturday Evening Post, Little Lulu. From the first panel, where the boys greet the arrival of rich brat Wilbur van Snobbe, to the very last, where the boys, chastened, can only marvel at Lulu’s revenge, a tale of vengeance, toxic masculinity, and female self-worth plays out with an inexorable pacing worthy of Sophocles or Cormac McCarthy. It helped that the story was also utterly hilarious. Lulu was the creation of Marjorie Henderson Buell, who drew single panels of the tomboy character for The Saturday Evening Post. However, when Stanley started crafting Lulu’s own comic book with inker Irving Tripp, the stories blossomed into biting, laugh-out-loud sitcoms, with Lulu a feminist hero for the ages.

The boys, led by Lulu’s frenemy Tubby, explicitly ban her from their world with a “No Girls Allowed” sign on their clubhouse, but again and again Lulu foils their plots using her superior smarts and insight, before returning to her defiantly girlish activities without a hint of inferiority. The subtext showed that by rejecting girls and women, the boys were cutting off an essential part of their own humanity. Although the Stanley/Tripp stories were favorites for kids — Trina Robbins and many other women of the 1970s underground comix scene, which we’ll get into later, were fans — his flawless pacing and storytelling was an avowed influence on a range of famous creators on this list, from R. Crumb to Daniel Clowes and beyond. One of our contributors, Heidi MacDonald, a former editor of kids’ comics for Disney and DC, is fond of saying that if a writer had a hard time telling a story in eight pages, she’d hand them a collection of Stanley stories. If they didn’t get it after that, they never would.

Two-Fisted Tales No. 25 (1951)

Writer, penciler, and inker: Harvey Kurtzman; Colorist: Marie Severin; Letterer: Ben Oda

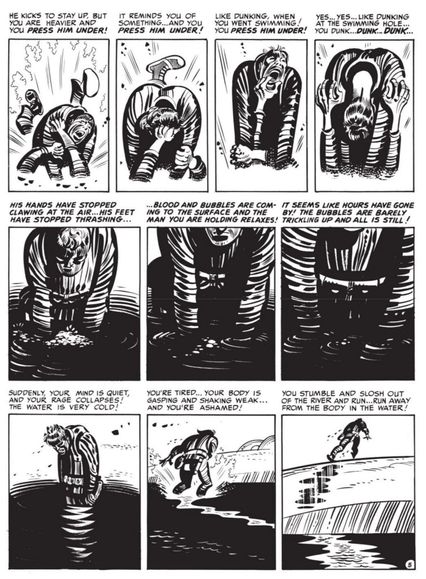

At the climax of “Corpse on the Imjin,” a tale of the Korean War, writer-artist Harvey Kurtzman delivers a page that combines formal rigor with brutal violence, as one man drowns another in Korea’s Imjin River. This often-studied page, frantic yet controlled, epitomizes Kurtzman’s gift for artful repetition. He used that gift dramatically in his war comics for EC, and humorously, with sudden, absurd gags to break up the rhythms, in his greatest gift to EC, the satirical Mad. Despite the stark difference between those two sides of his output, Kurtzman masterfully used page rhythms in both, making him one of comics’ chief formalists, as important to the comic book as Eisenstein was to cinema.

“Corpse” still packs a narrative punch. It reduces the genre of the war story to an elemental hand-to-hand fight between two unnamed soldiers, one American, one North Korean. The tale starts with the American musing about how remote and clinical warfare has become, but he is proven wrong when the North Korean, hungry and desperate, attacks. By the story’s pitiless logic, one man must kill the other. There is no glory in it, nor any patriotic affirmation of duty done; instead, the tale is poetically bleak and fatalistic, true to the Stephen Crane–like naturalism of Kurtzman’s best war stories. Remarkably, this harsh fable was published during the Korean War itself; this issue would have been released in about September or October of 1951, during a protracted and bloody stalemate in the War.

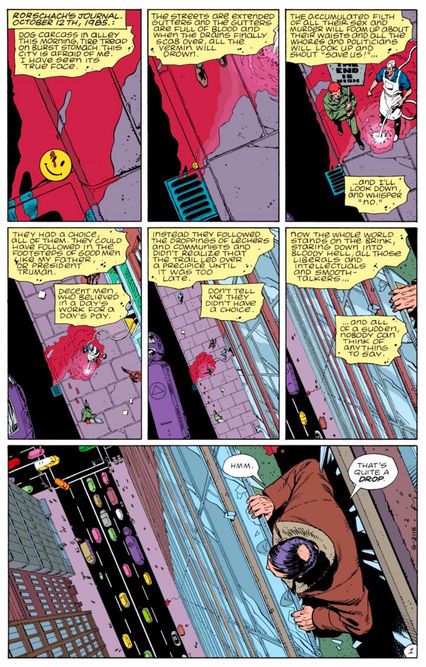

Many comics creators that came after emulated Kurtzman’s rhythmic control of page layout (see for instance our examples from Amazing Spider-Man No. 33 and Watchmen No. 1). Yet his thematic content also made waves: the underground comix generation, notably R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman, admired Kurtzman’s rough truthfulness and tragic humanism, even as they ate up the rude satire of Mad. But “Corpse” is arguably his masterpiece.

Four-Color Comics No. 386 (1952)

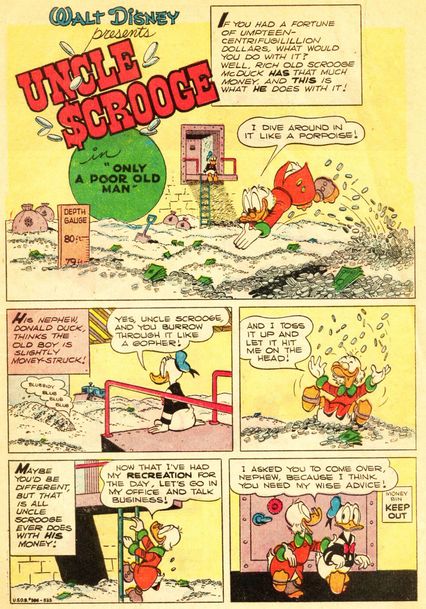

Writer and penciler: Carl Barks

“Only a Poor Old Man” wasn’t Scrooge McDuck’s first appearance — he’d been a supporting character in comics starring his nephew, Donald Duck, for years — but it was the issue that nailed down McDuck’s most notable manifestation of rampaging capitalism: diving in to his huge pile of money. McDuck was the creation of Carl Barks, an immensely imaginative cartoonist whose young adulthood spent working in various 19th-century professions — including cowboy and mule driver — left him with an appreciation for adventure and a firsthand knowledge of greed and stupidity. After becoming an animator at Disney, Barks discovered his greatest talent was as a cartoonist, and for 24 years he chronicled the Duck family and the world of Duckburg with shrewd characterizations that played up the foibles of human nature. Scrooge evolved from a penny-pinching miser befitting his Dickensian name to a more comedic and occasionally even good-hearted uncle to that shiftless slacker, Donald.

Barks’s animation-inspired storytelling and expressively comedic characters had a seminal influence on all the massively successful “funny animal” comics to follow — and beyond: R. Crumb names him as a major influence. Barks’s take on Donald and Scrooge would inform both the original DuckTales cartoon and its revival. Scrooge’s OCD fetishizing of wealth — many a tale begins with an assault on his “money bin” by the nefarious Beagle Boys — remains a potent symbol of the power and danger of a duck-amuck economy. And “diving into the money bin” has become a part of the language: a real-life Disney promotion based on the phrase even toured to promote the new DuckTales animated series.

Mad No. 4 (1953)

Writer: Harvey Kurtzman; Penciler and inker: Wally Wood; Colorist: Marie Severin; Letterer: Ben Oda

By 1953, Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood had been working for EC Comics for a few years, turning out serious war epics, thought-provoking science-fiction stories, and satirical (and gory) horror morality plays. When Mad debuted as a comic (it didn’t become a magazine until issue 24), it wasn’t setting the world on fire, sales wise. Then came issue No. 4 and “Superduperman.” The story, written with sharp wit and laid out by Kurtzman and featuring stunning art by Wood, became a instant hit, changing the fortunes of the comic. In the story, creepy assistant copy boy, Clark Bent, who is secretly Superduperman, lusts after Lois Pain, uses his X-ray vision to look into the ladies’ room, and is a generally pathetic figure. After a wild battle with Captain Marbles (who has become a villain), the triumphant Superduperman figures he can use his newfound glory to woo Lois. It doesn’t really work out.

The story turns the do-gooder superhero paradigm on its head by making both of the heroes into horrible people, which really hadn’t been done before. It also parodies the copyright-infringement lawsuit that the publishers of Superman, National, filed and won against the publishers of Captain Marvel a few years earlier. National threatened to file a lawsuit against EC Comics for the parody, but they never went through with it. Perhaps most notably, “Superduperman” was an avowed and massive influence on a decidedly unfunny comic: Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins’s Watchmen, which extrapolated on Kurtzman and Wood’s comedic deconstruction of superheroic self-delusion and entitlement. Mad continues to this day, outlasting its many imitators and still making fun of everything.

Haunt of Fear No. 19 (1953)

Writer: Al Feldstein; Penciler and inker: Jack Davis; Colorist: Marie Severin; Letterer: Jim Wroten

When Maxwell C. Gaines, founder of Educational Comics, died in a boating accident in 1947, his college-student son William M. Gaines inherited the company. Until that point, EC had put out wholesome, low-selling family fare like Picture Stories From the Bible. Max was reportedly abusive toward Bill, and in a bit of posthumous revenge, Bill took EC in a new direction with violent, irreverent titles like Tales from the Crypt, in which abusers get their comeuppance in spectacularly gory fashion. Many of the next few pages on our list prove that the newly rechristened Entertaining Comics wasn’t just one of the most successful publishers of the 1950s, it was also the most influential.

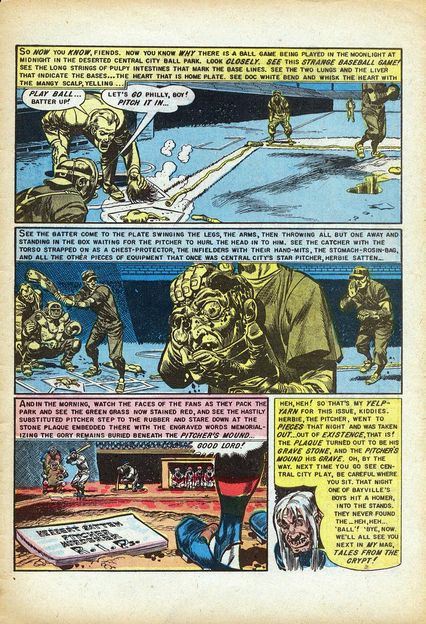

In “Foul Play!”, drawn by EC MVP Jack Davis, an evil baseball pitcher kills a rival player by sliding into him with poisoned cleats; the victim’s teammates get their revenge by dismembering him and playing a baseball game with his guts. Stephen King featured the story in his terrific survey of the horror genre, Danse Macabre, and infamous anti-comics crusader of the 1950s Dr. Fredric Wertham gave the page you see here a no less prominent, albeit less flattering, position in his best-selling Seduction of the Innocent. The success of Tales from the Crypt and its sister titles, Haunt of Fear and The Witch’s Cauldron, would inspire a wave of crappier, but equally as gory horror comics that would lead to anti-comics panic. (Not to mention much better things like Warren Publishing’s Eerie magazine and the King/George Romero collaboration Creepshow.)

We’d be remiss if we didn’t point out the coloring on this page by living legend Marie Severin, who started out at EC when she was just 20 years old. Note how Severin chooses to paint the goriest scenes in only two colors, to lessen the visceral shock while simultaneously allowing for all the gruesome details fans craved. For this reason Tales from the Crypt editor Al Feldstein called her “the conscience of EC.”

Impact No. 1 (1955)

Writers: Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein; Penciler and inker: Bernie Krigstein [as B. Krigstein]; Colorist: Marie Severin; Letterer: Jim Wroten

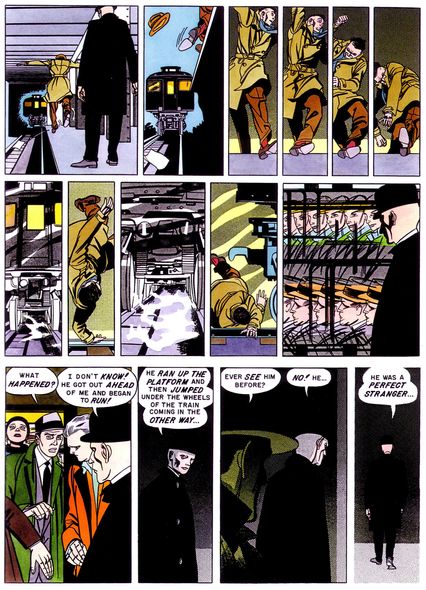

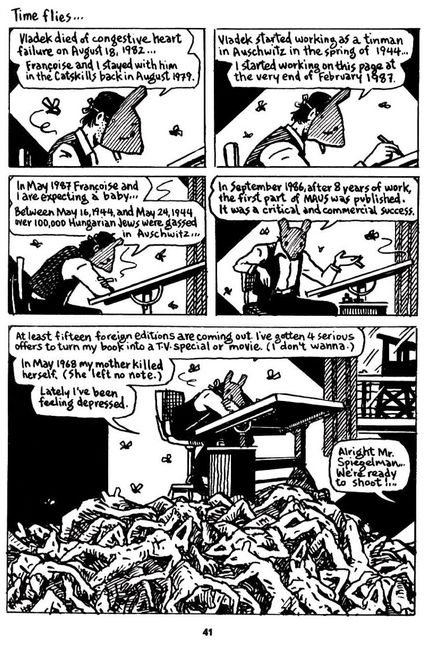

The page, powerful but perhaps unremarkable to the modern comics reader, may be the single most analyzed page in comics history. It had a strong influence on Art Spiegelman — who wrote about it for the New Yorker — and Frank Miller, who frequently mentions it in interviews. It’s the drawn work of Bernard Krigstein, a name nearly unknown to the average comics fan but revered among cartoonists from the ’50s on. Krigstein was an ambitious artist who, in 1955, found himself at EC Comics, when it was trying to reinvent itself as a more sophisticated publisher following the fateful establishment of the censorious Comics Code Authority in the wake of Fredric Wertham’s anti-comics campaign of the early 1950s. The story involves Reissman, a former concentration-camp guard, who sees one of his victims on a New York subway and falls to his death trying to escape him.

It wasn’t the bold story that made “Master Race” so revolutionary — although the Holocaust was only ten years in the past and rarely spoken of. It was how Krigstein told the tale, using repeated panels, fractured images and expressionist anatomy to capture Reissman’s panic and dark deeds, and to break down time into fragmented, strobe-light-esque instants. Although today these devices are established comics vocabulary, they were utterly revolutionary in their time and inspired countless artists who came after to experiment with their own storytelling. Or as Spiegelman put it in the New Yorker, “Krigstein began to vibrate with the inner language of comics, to understand that its essence lay in the ‘breakdowns,’ the box-to-box exposition that breaks moments of time down into spatial units.” Krigstein never drew another story with the impact of this one, but he didn’t need to.

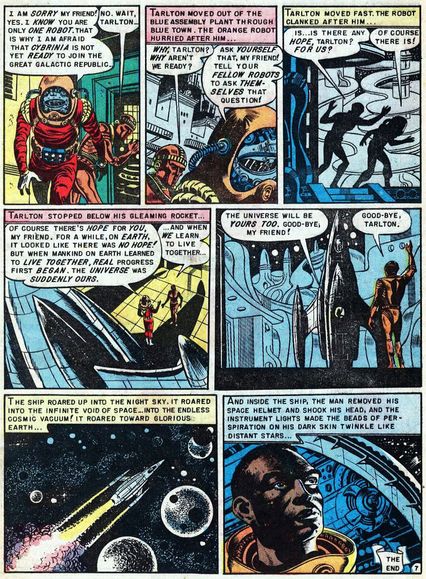

Incredible Science Fiction No. 33 (1955)

Writer: Al Feldstein; Penciler and inker: Joe Orlando; Colorist: Marie Severin; Letterer: Jim Wroten

When the comic-book industry banded together to form the Comics Code Authority in September 1954, EC Comics publisher William Gaines believed that the new rules were effectually designed to hurt his company. They banned the words “crime”, “horror,” and “terror” in comic-book titles, which directly targeted histop-selling series — Crime SuspenStories, The Vault of Horror, and Tales From the Crypt. Gaines tried his best to keep EC Comics afloat post-Code, and EC Comics launched a “New Direction” in 1955, with a collection of new series that they hoped would not offend.

However, at the end of 1955, they ran afoul of the Comics Code in the production of Incredible Science Fiction No. 33. The Code opposed a new story in the issue, “An Eye for an Eye”, by Angelo Torres, as being too violent. So it was replaced with a reprint of a classic Weird Fantasy story. Titled “Judgment Day,” it depicted an astronaut representing the Galactic Republic visiting the robot planet Cybrinia to see if Cybrinia could be included in the Republic. He has to turn them down because blue robots were treated worse than orange robots for no reason. As he flies away in his ship, he takes his helmet off and we see that he is black. The Comics Code would not allow the story unless the astronaut was recolored to be white. Writer Al Feldstein was outraged and so was Gaines. They threatened a lawsuit. Eventually, the Code relented and the story was published as originally drawn. However, this was the clear sign that EC Comics could not work within the parameters set by the Code, so Gaines ceased his comic-book production, concentrating instead on his popular humor magazine, Mad, which skirted regulations because it was technically a magazine. EC are sometimes accused of being shock merchants, but this page reminds us that they were also idealists.

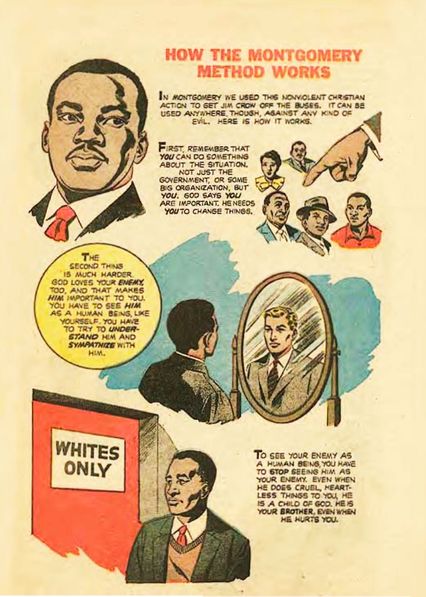

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story (1958)

Writers: Alfred Hassler and Benton Resnik; Penciler: Sy Barry; Letterer: John Duffy

The Fellowship of Reconciliation was formed in England in early 1914 in a failed attempt to prevent the outbreak of World War I. The following year, they opened up their American branch of the organization and have been serving the public good ever since. In the 1950s, they were directly involved with Martin Luther King Jr. in the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56. It was while working with Dr. King that the Fellowship’s director of publications, Alfred Hassler, came up with a brainstorm. He pitched the idea of producing a comic book that could serve to spread the message of the boycott. Essentially, he wanted to create a guidebook for nonviolent protesting.

Hassler worked with Toby Press to produce the comic book. Legendary cartoonist Al Capp lent a few artists, including one named Sy Barry, from his studio to draw it. Dr. King gave his own feedback on the comic book as well. The published work was a 16-page publication called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. It opened with a short biography of King’s life, then an “everyman” account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, followed by a detailed guide to how to do a nonviolent protest like the bus boycotts. 375,000 copies were printed — 250,000 in English and 125,000 in Spanish — and they were distributed through African-American schools, churches, and civil-rights groups. The protesters who became known as the Greensboro Four, who helped to desegregate Woolworth’s in North Carolina by having protest sit-ins, specifically cited The Montgomery Story as the direct inspiration for their actions. The success of the comic led to countless other political groups using comic books to express their message to the masses. Recently, in honor of The Montgomery Story, Representative John Lewis used comics to tell his autobiography in the award-winning and best-selling graphic memoir series, March.

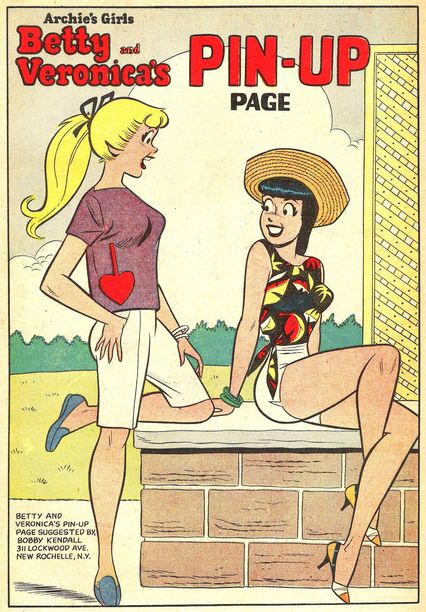

Archie’s Girls: Betty and Veronica No. 68 (1961)

Penciler: Dan DeCarlo; Inker: Rudy Lapick

In 1941, MLJ Magazines launched a teen humor feature based on a popular series of films starring Mickey Rooney as an everyteen. Titled “Archie Andrews,” it was a smash success, MLJ was renamed Archie Comics Publications in 1946, and every other comic-book company soon launched their own rip-offs. After Stan Lee hired Dan DeCarlo to work on Timely’s teen humor comics in 1946, DeCarlo became the most renowned teen-humor artist in the industry, working on Millie the Model for over a decade. When comic sales took a drop in the late 1950s, DeCarlo began taking more freelance assignments for Archie. The only problem: He had to draw in the style of the original Archie artist, Bob Montana, which slowed DeCarlo’s output down. Around 1960, they successfully got him to commit to them full time by letting him draw in his own style.

This 1961 pinup from Betty and Veronica No. 68 sees DeCarlo using his unique style on Archie’s famous girlfriends, including his distinct ponytail hair style for Betty, which was, oddly enough, a big deal at the time. Soon, every other artist at Archie had to draw like DeCarlo. As time went on, his style became one of the most influential in comics history, given that it became the official “look” for Archie Comics for the next 50 years. Along the way, DeCarlo also created some of Archie’s most popular new characters, like Sabrina the Teenage Witch and Josie and the Pussycats.

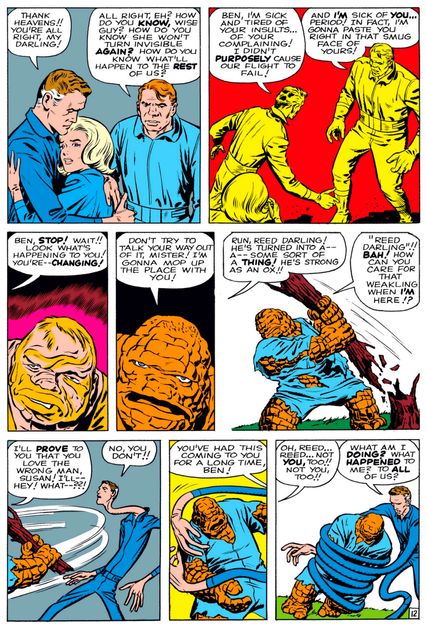

Fantastic Four No. 1 (1961)

Writers: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby (it’s complicated); Penciler: Kirby; Inker: George Klein; Colorist: Stan Goldberg; Letterer: Artie Simek

There is some confusion over why Martin Goodman was inspired to have Stan Lee bring back superheroes for the first time in nearly a decade to the comic-book company that was known as Atlas Comics at this point in time (was it really due to a National higher-up bragging about Justice League of America’s sales during a golf game with Goodman?) and there is even some dispute over who came up with the characters in the Fantastic Four. It was almost certainly through a collaboration between Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, but both men claimed it was their sole creation that they then brought to the other. (It did bear considerable resemblances to Kirby’s earlier work on DC’s Challengers of the Unknown). Either way, there is no doubt about why this story changed comics for good.

Even leaving aside the fact that the Fantastic Four gain their powers from stealing a rocket ship and then crashing it (it was the early 1960s, though, so at least they had a noble cause: beating the “Commies” to the stars), which was already an innovative superhero origin, the genius of Lee and Kirby’s Fantastic Four was clear as soon as they crashed, gained superpowers … and promptly began fighting with each other. These were superheroes who acted like actual people. They had genuine reactions to each other and their situation. This was the key to Marvel’s success in a nutshell: Real people, real problems, plus superpowers. Within a year or so, Lee and Kirby (as well as others, perhaps most notably Steve Ditko) were applying this formula to all their new heroes and the Marvel Age of Comics was born.

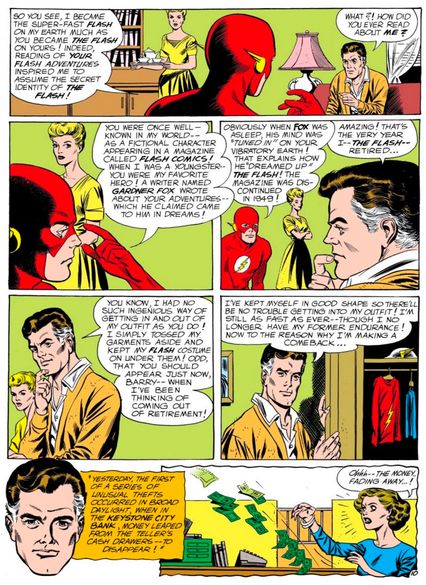

The Flash No. 123 (1961)

Writer: Gardner Fox; Penciler: Carmine Infantino; Inker: Murphy Anderson; Letterer: Gaspar Saladino

See the woman who’s wearing a dress the same color as her hair in the background of this Carmine Infantino–drawn page? One can only read her blank-faced silence as benumbed shock at the arcane exposition of superhero continuity being performed by two men in her living room. That guy on her right with the white temples, that’s Jay Garrick. He was the Flash in the ‘40s, see, during the Golden Age of comics, until his book got canceled. The guy on her left in the red hood, that’s Barry Allen. He became the Flash starting in 1956, and his creation begins what’s called the Silver Age of comics. As Barry says, he got the idea to call himself “the Flash” after gaining superspeed powers because he recalled reading comics about Jay’s adventures when he was a kid. So, in a way, Barry Allen is the first fan-turned-pro.

More notably, in this story, “The Flash of Two Worlds,” Barry learns Jay isn’t fictional. He’s very real, and his adventures happened in another dimension called “Earth-2.” It is this concept — that every superhero story you ever read actually happened, even the “fictional” ones — that makes this page so important. For better and for worse, this notion of “continuity” is what keeps fans coming back to superhero comics decade after decade. This was the very first of many, many long-winded continuity explanations in comics history.

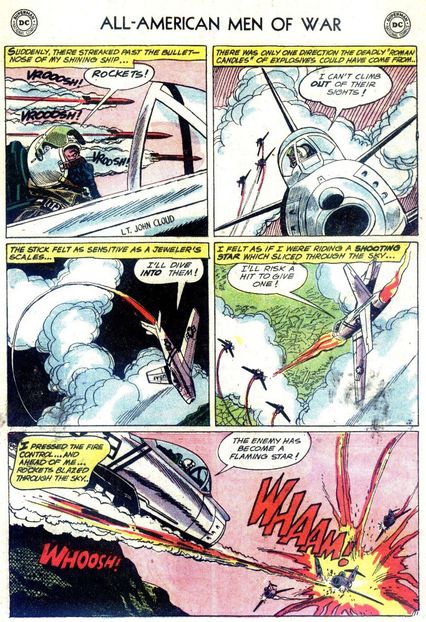

All-American Men of War No. 89 (1962)

Writer: Robert Kanigher; Penciler and inker: Irv Novick

We selected this page for its final panel, which Roy Lichtenstein appropriated for one of his most famous Pop Art paintings, Whaam!, currently hanging in the Tate in Liverpool, England. As part of his process, Lichtenstein cut out this Irv Novick panel from All-American Men of War, projected it on a wall, traced the line art, then painted it through a screen to mimic the so-called “Benday dot” effect employed in this era of comics printing. Lichtenstein made millions from these and similar paintings, but the artists who did the original comics? Not so much.

The Pop Art movement occupies a strange place in comics history. On the one hand, it informed things like Adam West’s Batman TV show, which drove thousands of readers to the comics racks. On the other hand, it reinforced the (almost entirely American) stereotype that comics were dumb crap made by hacks for morons. Warhol made Campbell’s Soup into “fine art” like Lichtenstein made romance and war comics into “fine art,” implying that without their divine intervention, both would remain mass-produced, disposable junk. (If you want to see side-by-side comparisons of Lichtenstein’s paintings and the comics he stole them from, check out David Barsalou’s excellent Flickr page, “Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein.”)

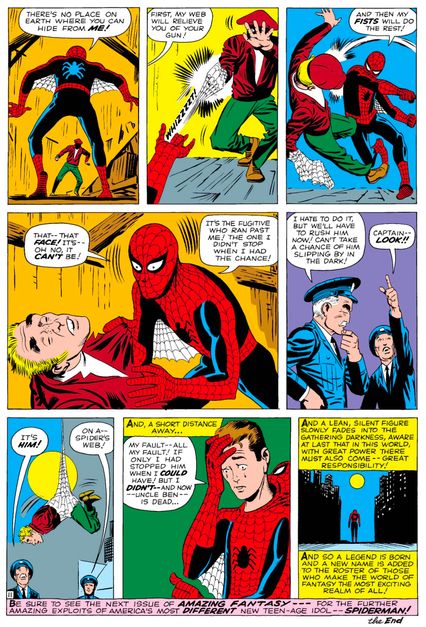

Amazing Fantasy No. 15 (1962)

Writers: Stan Lee and Steve Ditko (it’s also complicated); Penciler and inker: Ditko; Colorist: Andy Yanchus; Letterer: Artie Simek

The lead feature in 1962’s Amazing Fantasy No. 15, crafted by writer/artist Steve Ditko and writer Stan Lee, is one of the most efficiently constructed origin stories in comic-book history — and yet, the final page is so powerful that it practically obscures the impact of what came before it. Since the launch of Fantastic Four No. 1 a year earlier, Lee and Jack Kirby had applied their “real people with superpowers” approach to two other heroes: a scientist whose anger transforms him into a monstrous Hulk, and a handicapped doctor whose cane transforms him into a literal god of thunder. Working with Ditko on Spider-Man, however, Lee advanced the idea to a gut-wrenching new level.

After nerdy Peter Parker gets bit by a radioactive spider, he not only doesn’t become a superhero like a standard Silver Age hero, but he specifically goes out of his way to not be a hero. He instead decides to use his powers to make money and become famous. This is all setup for the shocking ending, when a criminal whom Peter didn’t stop while at a TV appearance later murders his beloved Uncle Ben. Ditko’s depiction of Spider-Man discovering the identity of his uncle’s killer is one of the most striking panels of the era. Then comes the famous kicker: “With great power there must also come — great responsibility!” Later versions of that phrase would be shortened and often attributed to Uncle Ben, but whichever form it took, Spidey would live by this principle for his entire career.

Avengers No. 4 (1964)

Writers: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; Penciler: Kirby; Inker: George Roussos; Colorist: Stan Goldberg; Letterer: Artie Simek

A mostly forgotten aspect of Marvel’s return to superhero comic books in the 1960s is that this was the second “return to superhero comics” that the company attempted after dropping their superhero line of books in the late 1940s. In the early 1950s, a superhero revival brought back their three major Golden Age superheroes: Captain America, the Human Torch, and Namor. The effort flopped, but that revival was on the mind of publisher Martin Goodman when he directed Stan Lee to start writing superheros again. Goodman’s instinct was to revive their earlier heroes, which led to the compromise of a new version of the Human Torch in the Fantastic Four. Then, once Fantastic Four proved to be a success, Fantastic Four No. 4 brought Namor back into fold. However, perhaps due to Captain America being so associated with the Golden Age, they held back on reviving him too.

But two years after Fantastic Four’s debut, Captain America returned in Avengers No. 4, firmly connecting Marvel’s past with its present. The Avengers discovered Captain America had been in suspended animation for two decades. In a stunning artistic sequence from penciler Jack Kirby and inker George Roussos, Captain America wakes up, realizes his partner Bucky is dead, sees he is surrounded by strangers, but then quickly gathers himself. That’s how awesome Captain America is — it took him mere seconds to adjust to one of the most shocking experiences imaginable. Bucky had actually been a regular feature in Captain America’s post–World War II comics (plus the abandoned 1950s revival), so the reveal that he had actually died back in World War II was the first major piece of retroactive continuity — known more commonly as a “retcon” — that Marvel unveiled, inspiring decades of similar continuity tweaks.

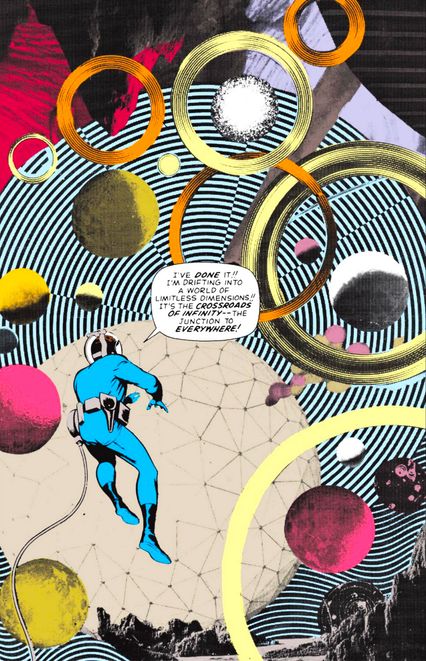

Strange Tales No. 138 (1965)

Writers: Stan Lee and Steve Ditko; Penciler and inker: Ditko; Letterer: Sam Rosen

By Marvel Comics’ glory period in the mid-’60s, Stan Lee’s lifelong penchant for spotlight-hogging had thoroughly alienated his two main artistic collaborators, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. By late 1965, Ditko had kicked Lee off co-plotting duties for the series they co-created, The Amazing Spider-Man, meaning Lee only added his distinctive dialogue flourishes after the comics pages themselves had already been completed. Ditko had also stopped consulting Lee on the other series he created for Marvel, “Doctor Strange” in Strange Tales, with no “co-” credit required here: Lee himself has admitted that Stephen Strange was Ditko’s sole creation.

While Ditko seemed to lose interest in Spidey at the end of his run, his love of Doctor Strange just got stronger, climaxing in an epic serialized battle between the Master of the Mystic Arts and his two main adversaries, Baron Mordo and the Dread Dormammu. The fight took place in a string of cliff-hanger tales for over a year, from No. 130 to No. 146, the first true continuous modern “story arc” as we know it. On this page, a highlight of the tale, Strange makes his way to the embodiment of the cosmos, Eternity, across one of the gonzo trans-dimensional vistas Ditko was known for concocting. These mind-blowing not-landscapes were a huge influence not just on cosmic comics, but on the whole ‘60s counterculture: Later this same year the first major psychedelic concert would be held in San Francisco, and it’d be called “A Tribute to Doctor Strange.”

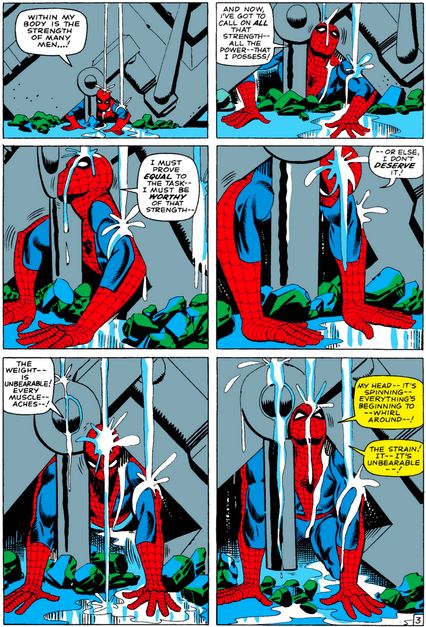

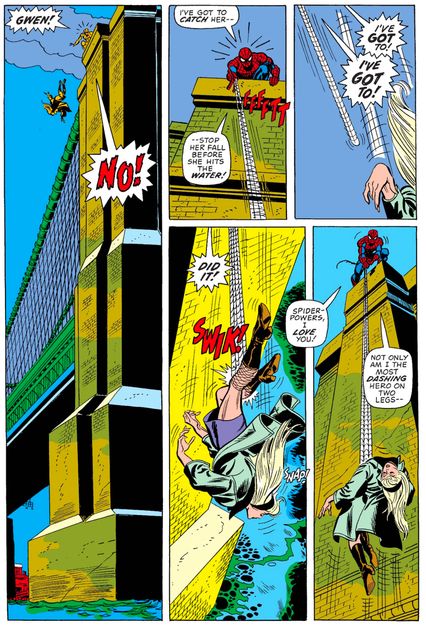

The Amazing Spider-Man No. 33 (1965)

Writers: Stan Lee and Steve Ditko; Penciler and inker: Ditko; Letterer: Artie Simek

Superheroes perform amazing feats of strength, speed, and skill seven times before breakfast. What makes this one of the most influential sequences in comics is that it depicts a superhero unable to do something, and struggling against his own failure — and how plotter/artist Steve Ditko makes several panels of a guy trapped under a pile of wreckage into incredible, moving reading.

In the previous issue, Spidey’s archnemesis Doctor Octopus dumped a whole bunch of machinery on top of him as water began flooding the villain’s underwater lair. To add to the tension, said lair also contains a McGuffin — er, a rare isotope that will save the life of Peter Parker’s Aunt May. Even though our rational minds may tell us, There’s no way they’re gonna kill off Spider-Man in the first five pages of a comic, Ditko’s storytelling skill is such that, emotionally, the tension and stakes have been raised so high that, for a second, you think that maybe the hero won’t come out on top this time. That’s why this is one of the most referenced and consulted sequences in superhero history, even making its way into the climax of the film Spider-Man: Homecoming.

Fantastic Four No. 51 (1966)

Writer: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; Penciler: Kirby; Inker: Joe Sinnott; Colorist: Stan Goldberg; Letterer: Artie Simek

Super-scientist Reed Richards discovers what will come to be known as the Negative Zone, an other-dimensional realm rendered in photo-collage and delirious abstraction. This pure exercise of Jack Kirby’s visual imagination is not the first photo-collage to appear in Fantastic Four, but marks the first time that Kirby used a full page to depict a hero’s passage between worlds. Fantastic Four No. 51 thus establishes an ecstatic new phase in Kirby’s art. Reportedly, he conceived of the Negative Zone as a setting to be rendered entirely in collage, and although that idea proved too impractical, this issue and this page would unlock many future examples of Kirby’s sublime otherworldliness.

In the mid-’60s, Kirby introduced complex plots — emphatically scripted by editor Stan Lee — and a bevy of long-lasting figures, many of them in Fantastic Four. If his early-’60s art had suffered for his massive workload, by 1965 he was concentrating on fewer books and tighter, more lavish and detailed pencils: the quintessence of his mature style. At the same time, he was pushing his art into areas where even his drawing could not go. This seminal page not only proved a watershed for Marvel continuity by introducing the oft-used Negative Zone, but also by suggesting a kinship between Kirby and fine-art collage in Surrealism and Pop Art. Further, it anticipates the mixed-media work of such later comics artists on this list, such as Jim Steranko, Bill Sienkiewicz, and Dave McKean.

Fantastic Four No. 52 (1966)

Writers: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; Penciler: Kirby; Inker: Joe Sinnott; Colorist: Stan Goldberg; Letterer: Sam Rosen

As Marvel grew in popularity in the mid-’60s, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby began to use the newfound fame of their comic-book series to address the societal issues of the era. When he reflected on the creation of the Black Panther, Kirby noted, “It suddenly dawned on me — believe me, it was for human reasons — I suddenly discovered nobody was doing blacks. And here I am a leading cartoonist and I wasn’t doing a black.” Kirby began developing a new black superhero (the first black superhero since All-Negro Comics No. 1’s Lion-Man) for Marvel, with the initial intent that the character would have his own new series. Marvel’s then-restrictive distribution system, which limited how many ongoing series they could release, forced Black Panther out of his own series and into the pages of Fantastic Four No. 52.

Originally, Kirby designed Black Panther’s costume with a cowled mask, a la Batman, but publisher Martin Goodman reportedly feared that Marvel might have a hard time seeing their comics distributed in the Southern United States with an openly black character on the cover, so they gave Panther a full face mask. The moniker was unrelated to the political party of the same name, which had yet to officially form (the name had already been in use in African-American political circles, so Kirby and Lee did not coin it). What was especially notable about the introduction of Marvel’s first black superhero is that we meet him as he single-handedly defeats the entire Fantastic Four as part of an elaborate test of his skills. They did not simply want to introduce a new black superhero; it was important to make him stand out from the crowd. The success of the Black Panther paved the way for all other black superheroes who followed, as well as for the astounding success of his feature-film adaptation.

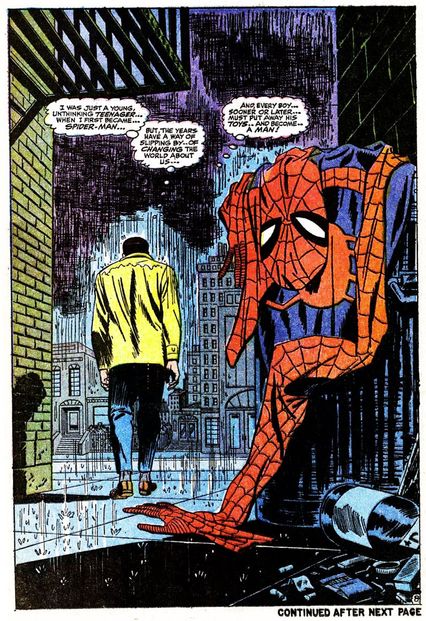

The Amazing Spider-Man No. 50 (1967)

Writer: Stan Lee and John Romita; Penciler: John Romita; Inker: Mike Esposito; Colorist: Stan Goldberg; Letterer: Sam Rosen

After working on his co-creation for almost four years, Steve Ditko ultimately had enough with Marvel Comics and decided to leave the company. Marvel had a pretty good idea that Ditko was ready to leave, so writer/editor Stan Lee had Spider-Man guest star in an issue of Daredevil to see how that series’s artist, John Romita, could handle the character. Romita must have passed muster, as he moved over to take over Amazing Spider-Man from the departing Ditko with issue No. 39.

Initially, Romita drew the book in Ditko’s style. You could barely tell that Ditko was gone. As it became clear that Dikto wasn’t coming back, Romita slowly began to take over the approach of the book. He rounded off some of Ditko’s edgier qualities and made Spider-Man (and especially Peter Parker) a good deal more accessible to a mainstream audience. One of the ways that Romita put his stamp on the title early on was visible in Amazing Spider-Man No. 50, when Romita and Lee shocked readers by having Peter Parker quit his superhero-ing. (He got over it, don’t worry.) As Spider-Man’s popularity increased, public came to identify with Romita’s version of the character rather than Ditko’s. Romita’s Spider-Man remained the version used on all licensed material for the next two-plus decades, although his direct involvement with the series itself scaled back once he became Marvel’s art director in 1973. In subsequent years, the notion of Spidey hanging up the tights has become just about as commonplace as lectures about great power and great responsibility, but Lee and Romita did it best.

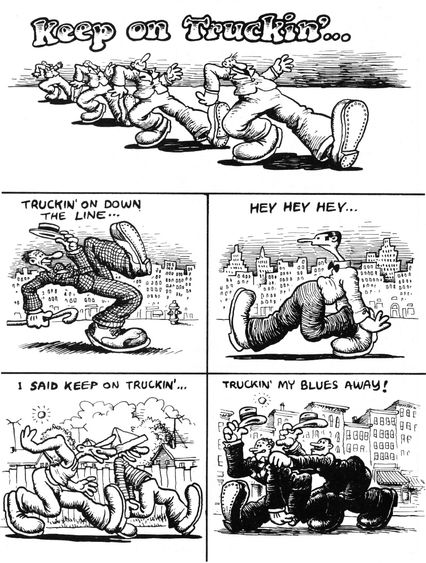

Zap Comix No. 1 (1968)

Writer, penciler, inker, and letterer: Robert Crumb

Robert Crumb grew up in the 1950s as a fan both of Dell’s Disney output and Harvey Kurtzman’s satire comics. His older brother made him draw their own Dell-style comics, forcing him to develop cartooning skills that served him well after high school, when he got a job as a staff artist at the American Greetings card company in Cleveland. Nevertheless, when the opportunity arose for him to go to New York and work for Kurtzman at one of his post-Mad comedy magazines, Crumb leapt at the chance, only to arrive and find that that magazine, Help!, had folded. Broke and stuck in New York, Crumb began dropping LSD, still legal then and prescribed to his then-wife by her psychiatrist. Psychedelic drugs twisted the cartoon images instilled in his brain since childhood into new and exotic forms. Crumb would say that it was during this “fuzzy period” that he created all the characters that would later make him famous: Mr. Natural, Flaky Foont, Angelfood McSpade, and this strip, “Keep on Truckin’.”

After relocating to San Francisco, Crumb and his wife would sell his Zap Comix on the sidewalk out of their baby carriage, and the uncensored rawness of Crumb’s acid-fueled strips single-handedly started the underground movement. The nonsensically optimistic “Keep on Truckin’” became something of a heraldry crest for the easy-going hippies, appearing on all manner of merchandise for which Crumb never saw a dime. Crumb would later claim to hate being a counterculture icon: “I got too much love,” he has said. He pushed back by plumbing the depths of his id for a series of misogynistic and racist strips to alienate his allegedly progressive audience, rendering “Keep on Truckin’” uncharacteristically quaint by comparison.

Strange Tales No. 167 (1968)

Writer, penciler, and colorist: Jim Steranko; Inker: Joe Sinnott; Letterer: Sam Rosen

While Marvel Comics did not necessarily have a “house style” in the ‘60s like, say, Dan DeCarlo’s Archie Comics, they clearly were driven by the superhero stylings of Jack Kirby. Kirby was the man who launched most of Marvel’s titles; when Kirby left a series, they would have him provide layouts for the incoming artist, so that the new artist could more easily follow his style. This worked out well for Marvel because Kirby was just that good, but at the same time, if you don’t give artists room to grow, there is a danger of stagnation. That was never something Marvel had to worry about, though, with Jim Steranko.

A former professional escape artist (no, seriously), Steranko was the rare penciler who showed up at the Marvel offices with a portfolio and wasn’t just hired, but was given a regular feature immediately. Steranko took over the Nick Fury feature in Strange Tales from Jack Kirby. As was general company policy, Kirby provided layouts for Steranko’s first issue. However, Steranko soon took off in his own direction: He merged comic-book art with Pop Art, the psychedelic with the surreal. Perhaps the best example of Steranko’s flair for the different was on his revolutionary four-page image in Strange Tales No. 167 — a spread that would require you to buy multiple copies of the book for you to see the full thing. Marvel editor Roy Thomas said it best: “I think Jim’s legacy to Marvel was demonstrating that there were ways in which the Kirby style could be mutated, and many artists went off increasingly in their own directions after that.”

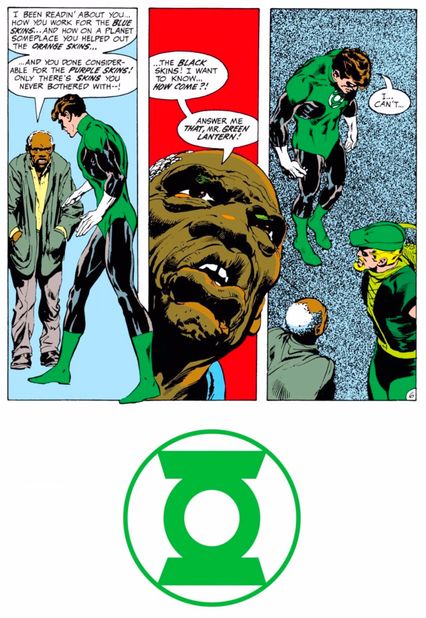

Green Lantern No. 76 (1970)

Writer: Denny O’Neil; Penciler and inker: Neal Adams; Colorist: Cornelia Adams; Letterer: John Costanza

As often happens, a major innovation arrived in something that was on its last legs and thus had nothing to lose. When writer Denny O’Neil and artist Neal Adams took over Green Lantern, it was on the verge of cancellation, so editor Julius Schwartz gave them the go-ahead for a story line wherein space hero Hal Jordan decides his powers could be put to better use helping the downtrodden people of Earth. He teams up with newly woke archer Green Arrow, who introduces his fellow Justice Leaguer to an old man on a ghetto rooftop who delivers this famous speech. The emerald duo then embarked on a series of social-issue-of-the-month adventures, tackling various ills like overpopulation, drug addiction, and pollution the only way superheroes have known how since Action Comics No. 1: by punching them in the face.

Their efforts seem a little cringeworthy today, like your dad trying to be cool while wielding an extraterrestrial ring of power; indeed, the ultraestablishment New York Times featured this rooftop scene in a typically condescending survey of superhero wokeness. The Arrow-co-starring run on Green Lantern wound up not selling very well, but was hugely influential among creators young enough to be hippies themselves and ushered in a new generation of socially aware heroics. (By the way, if you’re wondering why it’s just two-thirds of a page: This was back in the days when DC would run ads on some story pages where that Green Lantern symbol is now.)

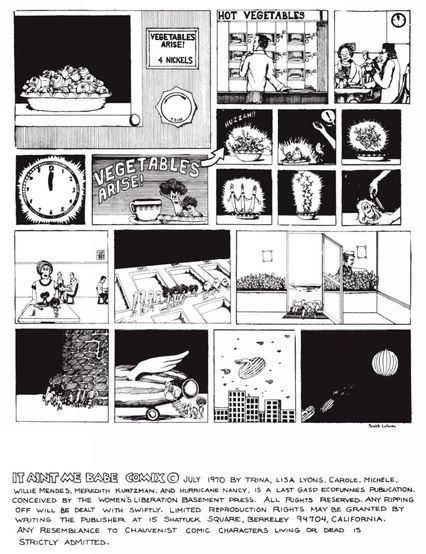

It Ain’t Me Babe Comix No. 1 (1970)

Writer, penciler, inker, and letterer: Meredith Kurtzman

A perfect confluence of events made the underground comix movement financially viable. Post-adolescents had been turned back onto comics in the ’60s thanks in no small part to the Marvel revolution, and as they grew older, they hungered for even more edgy fare. Simultaneously, the counterculture movement inspired a big boom in “head shops,” stores that sold cannabis paraphernalia to the counterculture crowd (mostly in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco). These stores were always looking for new things to sell that appealed to their regular clients and since comics were “cool” again, head shops began to sell work like R. Crumb’s aforementioned Zap Comix. It was a great time to be in the underground … if you were a man, that is.

The underground comix business model was built on group efforts. A fellow decides to put out a new comic and he asks Friends A, B, and C to work on it. The issue was that it was only guys asking other guys. The handful of female underground creators, like Trina Robbins and Barbara “Willy” Mendes, would never be invited to participate in these comix and were stuck having to pitch to underground newspapers. Robbins and Mendes decided that their only way of breaking into underground comix was by forming their own female-only group effort. Robbins had been doing comics for the feminist newspaper It Ain’t Me Babe, so she used that name for their one-shot comic, featuring a cover with famous female comic characters raising their fists in solidarity with women’s liberation. The book was a major success, selling 40,000 copies over three printings, proving that there was a market for female-created and female-driven underground comix. This particular page features a clever women’s-liberation allegory comic (made by Harvey Kurtzman’s daughter, Meredith), but the real action is in the all-female credits at the bottom.

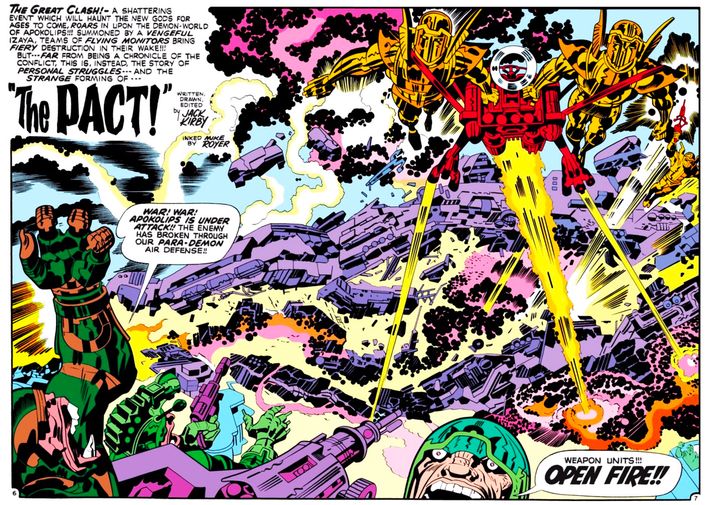

The New Gods No. 7 (1972)

Writer, penciler, and colorist: Jack Kirby; Inker and letterer: Mike Royer

In the early ‘70s, Kirby decamped to rival publisher DC, where he turned costumed heroics into a personal mythos that exceeded even his wild flights at Marvel. His so-called Fourth World saga, a cluster of four interwoven titles, and in particular New Gods, brought a Biblical sense of scale to the genre. New Gods envisioned two warring worlds: New Genesis, led by the saintly Highfather Izaya, and Apokolips, ruled by the stony nightmare known as Darkseid, a despot whose goal was control of everyone and everything — “Anti-Life,” as Kirby put it, the quintessence of fascism.

“The Pact,” a chapter withheld until a year into the New Gods series, tells an origin for its patriarchal succession myth: In a failed bid for peace, the ferocious Orion, son of Darkseid, is traded to New Genesis in return for Scott Free, son of Izaya, who is sent to Apokolips. Orion, warlike, tormented, is the linchpin of New Gods; raised in New Genesis, he will fight the evil of Apokolips. Scott, also damaged, will weather the hell of growing up on Apokolips and become the hero of New Gods’ sibling title, Mister Miracle. But more than anything, “The Pact” is a war story and a parable about how violent conflict poisons all sides. When his partner Avia is murdered, Izaya vengefully wreaks warfare and destruction on Apokolips, until he realizes that he has succumbed to “Darkseid’s way.” This is a spread near the start, in which Kirby pushes his violent graphic mannerisms as far as they will go: crowded, multiplane depths and drastic foreshortening; bold cropping of figures; and the dot-based, fizzing rendition of energy (so-called Kirby Krackle). It’s a riot of Kirbyism, implying his own memories of shelling, strafing, and battlefield terror in World War II. Superheroes ever since, on page and screen, have sought to inhabit this same outsize sense of grandeur and threat.

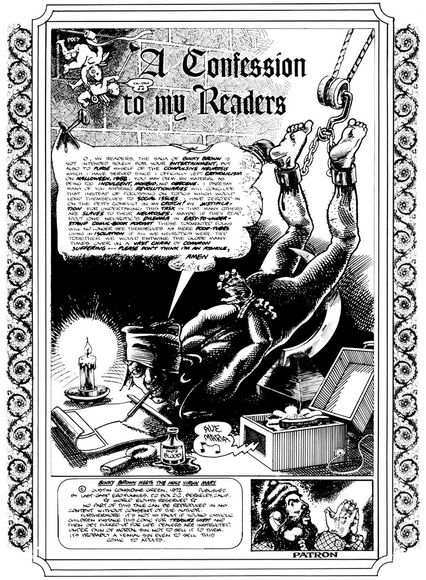

Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972)

Writer, penciler, inker, and letterer: Justin Green

At once sacrilegious, comic, and scary, this introductory page by cartoonist Justin Green imagines the work of making his autobiographical comic, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, as an act of penance and a form of torture. As if aware that there has never been a comic book quite like this, Green asks the reader’s indulgence from the outset, even as he mocks his own suffering. The threat of castration — so apt for a book about sexual guilt — hovers over Green as he seeks to explain, or excuse, this story about adolescence, religious mania, and what Green has since recognized as his OCD. Young Binky (Green’s stand-in), raised up in a hygienic postwar America that seethes with repressed weirdness and anxiety, comes to believe that his sexual fantasies are radiating outward from his body as invisible rays that threaten to strike representations of the Blessed Virgin Mary. From there, Binky Brown depicts a full-on plunge into hyperscrupulous overcompensation and self-torment, as filtered through an unsettled visual imagination.

Based on its topic, you might think that this pioneering confessional comic would be a drag. It’s anything but. Binky is at once shameful and shameless, appalling and thrilling, embarrassing, excruciating, and hilarious. It’s genuinely funny, but the laughter comes shrink-wrapped with guilt, because this is a true and terrifying story. “NSFW” does not begin to cover it; sensitive readers may cringe. Reading Binky means getting inside Green’s head, where religious iconography, phallic symbolism, and satiric riffs on both high and low culture are incised with a stunning technique worthy of Albrecht Dürer. It’s outrageous, sure, but it’s also a gutsy, harrowing work of art. The confessional vein of underground and alternative autobiographical comics begins here. Without Binky, Art Spiegelman has said, there would be no Maus — and other autobio trailblazers, including Aline Kominsky and R. Crumb, have declared their debt as well. Binky, wellspring of one of the key genres in 21st-century comics, is a scabrous and irreverent masterpiece.

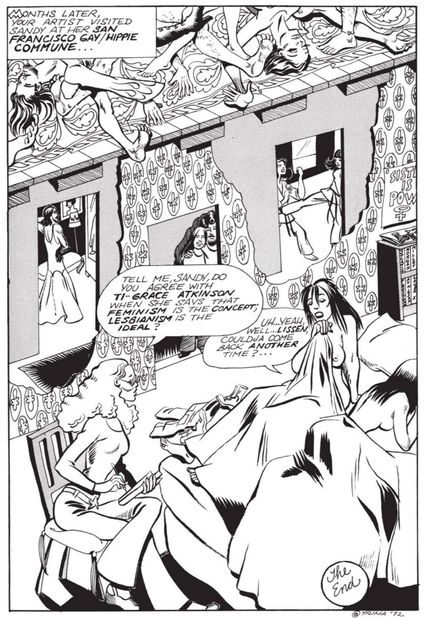

Wimmen’s Comix No. 1 (1972)

Writer, penciler, inker, and letterer: Trina Robbins (as Trina)

Following the success of It Ain’t Me Babe Comix, artist Patricia Moodian was able to convince Ron Turner (of Last Gasp comics, who published the comic book), to do a follow-up ongoing series that followed in that same women’s-liberation theme. Moodian was the original editor (she insisted that different women would edit every issue going forward), a job she achieved, she later recalled, “simply because I took the initiative to do the work it took to get a publisher and gather together the women who would be interested in such an opportunity.” Moodian collected an initial group of ten female creators in total — including Trina Robbins, Aline Kominsky, Michele Brand, and Diane Noomin — and they created Wimmen’s Comix No. 1, an anthology that gave female creators a wide berth to try whatever type of subject matter (or genre) that they wanted to tell.

That said, most of the stories tended to tell stories concerning feminist issues of the day. For her contribution to the first issue, Robbins wrote “Sandy Comes Out,” about her former roommate, Sandy Crumb Pahls, who gave Robbins her blessing to write about her experience. That the first non-pornographic comic-book story about an out lesbian character was written by a heterosexual woman caused some controversy at the time, but as Robbins later noted, it inspired one critic, artist Mary Wings, to create her own comic, Come Out Comix. Wimmen’s Comix intentionally sought out new creators, thereby publishing some of the earliest works by a number of new comic-book creators. The series was very influential on the next generation of progressive artists, like Phoebe Gloeckner (who had one of her earliest works in an issue of Wimmen’s Comix), Alison Bechdel, and Howard Cruse, who based his editorial approach for the radical queer series Gay Comix on Wimmen’s Comix.

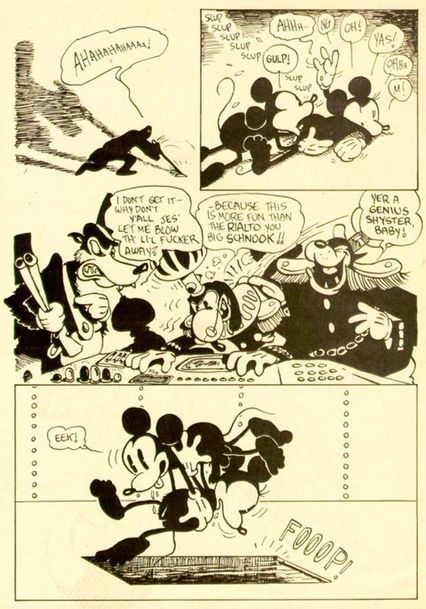

Air Pirates Funnies No. 1 (1972)

Writer, penciler, inker, and letterer: Bobby London

Without permission from the fine folks at the Walt Disney Company, founder Dan O’Neill, Bobby London, and their fellow troublemakers in the Air Pirates underground cartoonists’ collective just decided to put out their own Mickey Mouse comics, albeit ones in which Mickey and pals cursed, jerked off, smuggled drugs, and orally pleasured their partners, as you see here with Mickey performing cunnilingus on Minnie. Whether this was all part of a dubious scheme to seize the copyright of the characters or just to poke the eye of an ultraestablishment entertainment conglomerate is a little unclear — and we’ll venture to say it was a little unclear to the Air Pirates at the time too.