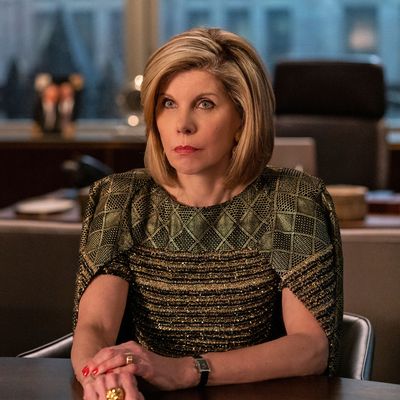

The way we move through the world often betrays our most intimate selves. This thought leaped into my mind as I walked through my neighborhood on an exceedingly rare spring day in Chicago recently. I found myself studying the people around me. A mom with a blonde bob pushed a stroller with single-minded determination. A couple held each other so tight, it seemed like they were afraid of floating away like forgotten balloons. A gaggle of black kids on Milwaukee walked with bounce and vigor, as if they were on the verge of dance. Midway through the sixth episode of The Good Fight’s tremendous third season, whose finale aired Thursday, Diane Lockhart’s signature grace is traded for a walk as pointed and cutting as a blade.

When we first met her ten years ago on The Good Wife, in the annals of Lockhart/Gardner, Diane was an easily aspirational figure — her grace is undeniable, her intelligence formidable, and her wardrobe enviable. She scanned as an example of insurmountable womanhood, someone who had figured out how to excel by navigating the rules of the world with aplomb. But what happens when the rules you live by — truth, justice, and democracy itself — cease to exist?

In the third season of The Good Fight, this has proved to be the rich seam of Diane’s arc. Her character wrestles with retaining her morality and utilizing her anger in this chaotic political moment. In the process, her body language changes from her signature self-assured grace to a sharply pointed threat. And in doing so, showrunners Michelle and Robert King offer something more fulfilling than a textureless aspirational figure with easily packaged feminism, but a character struggling with how to live in a time when chaos has seeped into every sphere of her life.

Early on in The Good Wife, Diane’s aspirational qualities were evident in her physicality. From the very beginning, Baranski has imbued the character with a grace that made it seem like she was gliding through the courtroom. Her posture was straight, and she took up space with both her body and her voice. This isn’t to say she wasn’t complicated. The best moments in Diane’s arc on The Good Wife are when she lets her guard down. Consider, when Kurt McVeigh (Gary Cole) — think a modern Marlboro Man and staunch conservative with surprising kindness — shows Diane an automatic assault rifle in his elaborate gun shed. It is one of the most sexually charged moments in the series. Her gaze follows his jawline and the curve of his lips as he moves around her. It’s as if she’s undressing right before our eyes, peeling off layers of control. It’s around Kurt, in the throes of lust, that we see Diane begin to appear disheveled. Midway through the fifth season, when her partner Will Gardner (Josh Charles) dies in a courtroom shooting, her body crumbles at the news. And finally, in the finale, comes the infamous slap. In the face of Alicia Florrick’s betrayal — who used an affair Kurt had with one of his former students to gain leverage in a court case — Diane looks her firmly in the eye and slaps her without saying a word. It’s a “fuck you” in physical form. This moment, more than any other, acts as a precursor to Diane’s journey on The Good Fight, defining her relationship to anger and the ways it manifests in her physical self.

When The Good Fight began in 2017, Diane was already beginning to fray at the edges. She lost her money in a Ponzi scheme run by Harry Rindell, a clear Bernie Madoff figure in the first two seasons, and wasn’t allowed back into the firm that once carried her name. So, alongside her goddaughter Maia Rindell (Rose Leslie), she found herself navigating new spaces, in which she was no longer in control of her own life. It’s not until the second season that Diane truly becomes the show’s lead, and the emotional/ethical center of the series. It’s here that Diane contends with increasingly knotty situations: Lawyers are being killed in the streets; she becomes a target; she develops an acrimonious dynamic with her new partner, Liz Reddick (Audra McDonald); she ramps up her efforts to dismantle Trump; and she has to face the strange impasse she’s found herself at in her estranged marriage to Kurt. Perhaps the true turning point in season two is when Diane realizes that in order to win a case, she needs Kurt’s testimony, which brings up all the unspoken issues of the affair he had with a former student. Diane is composed, at first, but the rage roiling inside of her is evident. “So, you’re loyal to her?” she says with contempt. “[But] not my firm, not my client, not to me.” As tears well up in her eyes, she emphatically says, “I will not be that wife.” This is the first moment we see the full scope of her anger without the mask of genteel elegance; we also see one of its roots: a refusal to lose a shred of autonomy or have her story defined by anyone else.

At first, Diane’s reaction is to run from her problems. She turns to microdosing hallucinogens and a torrid affair that has repercussions for her professionally. But when she discovers an aikido class in the back of a laundromat on a strange, rainy night, something in her shifts.

Showrunners Michelle and Robert King pitched the idea of Diane finding a venue for her anger through meditation or religion. Baranski felt it wasn’t active enough and suggested kung fu instead (her daughter had been studying it at the time). “[The Kings] then came up with aikido because it is graceful and has to do with receiving violence and then overturning it. It’s not about being an aggressor,” Baranski told me in a recent phone interview. But it soon becomes clear that aikido is not the right venue for Diane, either — and not just because her instructor starts blathering on about a “Jewish conspiracy” during meditation. She was being too aggressive, embracing anger rather than transmuting it, as aikido calls for; her interactions with other students were filled with aggressive displays of power. It makes sense, then, that Diane turns to ax-throwing — a physical outlet that matches the intensity of her anger. Ax-throwing allows for a marriage of Diane’s everyday grace, her ability to relish life, and most importantly, her newfound ability to treat anger as fuel. We see this in her exhilarated awe as she studies and buys exquisite, hand-carved Bavarian axes. It is evident in the assured focus of her gaze and movements. It’s only her and her target, only her and her goal.

Diane’s relationship with anger proves useful considering this season’s main villain, Ronald Blum (Michael Sheen) — a fentanyl lollipop sucking, forever manipulating, aggressively egotistical conservative lawyer who carries himself with such unabashed vulgarity and rancor you can practically smell him coming off the screen. Blum tries to act as an ally of sorts, worming his way into the Reddick, Boseman & Lockhart firm through legal maneuvering. In the sixth episode, he appears at Diane’s ax-throwing range, making broad, saccharine ploys to get at her good side in order to have a partner supporting his bid to become one as well. He snakes his way toward Diane, telling her she reminds him of his mother and how irresistible his pheromones are. She remains focused on the bull’s-eye, hitting it with precision. The only noise interrupting Blum’s self-indulgent prattling is Diane’s occasional, mirthful chuckle and the thunk of blade hitting wood. Until Diane turns to Blum. “I know what this is,” she begins. “You’re compelled to defile, Mr. Blum. It’s pathological. And you may think you’ve made some inroads at my firm, but I promise you it won’t last. Because your tactics work and I am happy to become you in order to get you the fuck out of my way.” Diane’s relationship to anger is now channeled into ax-throwing in ways that allow her to not be consumed by the chaos around her, but instead fight back.

It would be easy, after this moment, to turn Diane into a gleaming paragon for moral verisimilitude. It would be earned in some respects, if a bit hollow. Instead, she continues to deal with her anger in ethically knotted ways, in particular when it comes to her involvement with a radical resistance group — cheekily referred to as the Book Club by its female denizens — whose tactics turn troubling and violent, creating a number of issues within her personal and professional life. She still has unexpected bursts of anger, especially as the tangled issues of race continue to thrum at the forefront of the firm. But by the end of this season it isn’t anger that defines the way she moves through the world. The finale, “The One About the End of the World,” sees Diane as not a hardened warrior but someone softer and more vulnerable than I expected, perhaps because the foe she’s facing is unexpected: her goddaughter and former Reddick, Boseman & Lockhart associate, Maia Rindell. In the face of how jaded Maia has become after joining Blum’s cause, Baranski softens her performance considerably. She’s left emotionally bare — the shock written on her face as she sees Maia alongside Blum in court.

For Diane, the richest moments are the quietest in the finale, far away from the courtroom. Look at the tender way she whispers “yes” when Maia asks if it is weird that they find themselves in this strange, antagonistic place. Look at the way she studies Blum as he hits on her by candlelight — her gaze both amused and clearly indicating how pathetic she finds him — before she walks out. Look at the sadness in her eyes, the softness in her posture as Maia turns down Diane’s offer to come join the firm as a partner. It is evident in the final moments of the season — Diane’s hair loosely curled, staring up at the ceiling with bemused contentment as she breathily exclaims to Kurt in bed, “I’m happy” — that, all her issues aside, she’s found a sense of balance and peace within herself. As she says to Adrian, “I realized I have felt something I haven’t felt in a while: hope.”