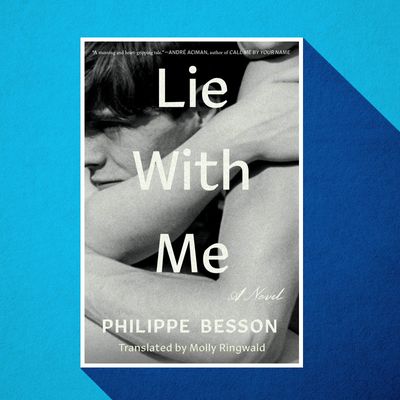

I don’t want to know if French novelist Philippe Besson’s newest book — a best-selling, prizewinning sensation in his home country, out here this week in a translation by the actor and writer Molly Ringwald — is based on his real life. I’ve dug around some, but my paltry French, mostly confined to curse words, hasn’t churned up much, and really it’s better this way. Lie With Me is designed to tempt you with such questions. Is it autofiction? A lightly fictionalized true story? A manipulative ruse designed to bond reader and novelist? Whatever it is, the story — imbued with the sprightliness of youth, the nostalgia of age, the deep internal echoes of regret — is all true, even if it’s not true. The “trick,” whatever it might be, need not be vivisected.

Lie With Me is the story of a successful (unnamed) French novelist — the kind who appears on roundtable intellectual TV shows that Americans wouldn’t stay up for — who catches a glimpse of what he thinks is a past lover in a hotel. Triggered by the sighting, he traces the story of his secret high-school affair with that lover: It was brief in tenure but formed the mold into which he has since tried to press every other romantic relationship.

In 1984 in Barbezieux, a town so small that the narrator insists it “doesn’t exist,” he remembers himself as a bookish young boy; the other boys whisper or yell that he’s a “dirty fag” because he has no girlfriend. “Of course I ‘prefer boys,’” he tells us slyly. The particular object of his adoration is Thomas Andrieu, a good-looking boy with a crowd of girls who “circle him, constantly seeking his attention.” Thomas “likes his solitude … He speaks little, smokes alone.” And that — Thomas’s cool, mature-seeming reluctance to live fully in the world — is what draws the narrator to him. The boys meet for lunch, and then, over the next few months, develop a quickening rhythm. They meet first in clandestine spaces, then in the narrator’s bedroom, and eventually, in an act of daring, they cruise around on Thomas’s motorcycle. “I’m frightened when the wheels slip on the gravel on the dirt road, but the only thing that matters is that I’m holding on to him, that I’m holding on to him outside.” Their meetings are at first limited only to sex, but then take on the sort of charged, silence-filled communion that first love provokes.

Yes, this synopsis reeks of André Aciman’s Call Me by Your Name. Lie With Me even sports a blurb from Aciman (“A stunning and heart-gripping tale”) and a cover that bears more than a passing resemblance to his. Both are set in provincial, untrafficked European towns in the last years or days before the AIDS crisis. Each features a sheltered intellectual and a worldly seducer. But where Aciman’s novel flashes in the heat and salt of summer, Besson’s is soaked in heavy, sodden gray. And alas, Lie With Me makes no reference to sexually available stone fruits.

While the starring peach of Call Me by Your Name was the perfect metanym for that lush and gauzy tale, Lie With Me unpeels like a springy orange. The boys’ relationship is bare but segmented, each encounter entirely isolated from the others, with only a thin membrane to keep all that tart juice from bursting out. Lie With Me is single-minded in its focus, spare but lucid in its descriptions. “I slip down the straps of his tank top,” the narrator explains. “It seems to me that there is no other gesture more sensual, more stirring … I watch him doze and then his face rolls over to the left, instantly waking him up … [W]e stay in bed, kissing, sucking, and fucking.” The intimacy is ripe on the page; this is a novel is horny for itself.

One-third of the way through this slim story, the similarities to Call Me by Your Name worried me. Aciman’s book should stand alone (except for the sequel he himself is putting out this year). But somewhere shy of the halfway point, Lie With Me veers sharply into the nether lands of ironic quasi-autobiography. In direct asides, Besson press-gangs the reader into the role of confessional priest. He frequently follows up comments with “I told you this,” and talks straight to camera with such urgency that you feel, suddenly, like a voyeur who’s been invited to participate.

Did this really happen? The question that so irritates novelists clearly titillates Besson. His wistful narrator has written books called Un Garçon d’Italie; Son Frère; L’Arrière-saison — books with the same titles as Besson’s own back catalogue. The novel is dedicated to a Thomas Andrieu (1966–2016), who, if real, has at least those facts in common with the Thomas of the book.

But Besson is never as transparent as Rachel Cusk or Catherine Millet. Lie With Me is closer on the metafiction scale to far more playful works like Pale Fire. It’s slightly saner than Muriel Spark’s The Comforters and a little less narcissistic than Roth’s Indignation. By concealing the line between artifice and truth, Besson preserves it, and goes a step further (or a step backward, depending on your interpretation) from traditional metafiction. His narrator talks directly to us, but whisks a broom over his own tracks, erasing the certainty of his claims. “I specify that my books are fiction, that memoir doesn’t interest me,” he says at one point, even while telling this story about his own life. And then he claims to have “invented stories all the time, with so much authenticity that people usually ended up believing me (sometimes even I was no longer able to disentangle the true from the false). Could I have made this story up from scratch? Could I have turned an erotic obsession into a passion? Yes, it’s possible.”

Ultimately, these games are not a distraction from the romance and nostalgia but very much the point. Think about it: How much of our own teenage years do we invent? How much is cobbled together from other people’s stories and shellacked with a glaze of who we’ve become, rather than who we were? Probably … a lot. Besson’s method sucks you in as an accomplice to this kind of necessary self-delusion, and offers a tantalizing third way of considering our own pasts: not as true or false, but collected and restrung, like beads on a necklace. We shuffle our favorites to the forefront, worry them over, finger them absently, distort their shapes over time.

In French, the title of Besson’s ultimately moving and graceful novel is Arrête Avec Tes Mensonges, which essentially means “stop with your lies.” Oddly, for a work in translation, the punning English title works a bit better. Lie With Me. Take me in your arms. And let’s agree to tell our own stories however we damn please.