It feels downright spooky that a starry revival of Terrence McNally’s Frankie & Johnny in the Clair de Lune should pop up on Broadway just in time to join a starry revival of Lanford Wilson’s Burn This, playing a block away. It’s like that Hollywood phenomenon of releasing weirdly similar movies at the same time. (Armageddon and Deep Impact, Babe and Gordy, A Bug’s Life and Antz — I mean, really?) Both plays premiered Off Broadway in 1987. Both are set in apartments in what now feels like a grittily poetic New York of yore. Both are bantery, unapologetically starry-eyed romances about straight couples, written by gay playwrights during the AIDS crisis, which gives them a complex feeling of escapism. (Burn This circles around the death of a gay character, but that death is pointedly untopical — a boat crash in the East River — and in Frankie & Johnny, only oblique references are made to the looming terror of the moment: “I get so sick and tired of living this way,” laments the play’s heroine, Frankie, “[like] we’re gonna die from one another.”) And both feature a man of massive, idiosyncratic personality aggressively shoehorning his way into the life of a skeptical woman.

Perhaps, for me, the current Frankie & Johnny — featuring Audra McDonald and Michael Shannon and directed without flourishes by Arin Arbus — is suffering a bit from unfair comparison. I found much to be interested in during Burn This (including the question raised by my colleagues in this essential piece of hard-hitting investigative journalism). By contrast, while McDonald and Shannon are both fun to watch, their turbulent chemistry alone doesn’t sustain McNally’s somewhat overstretched play. “Everything has phases,” say’s McDonald’s apprehensive, practical Frankie, and the play she’s in has too many. Frankie & Johnny is a one-act that’s been inflated into two. It’s not that witty, compelling moments don’t occur throughout, but the story only has one engine — will they or won’t they? — and the cycle of, in the immortal words of Rob Gordon, “attack and defense, invasion and repulsion” between the protagonists feels played out by the end of Act 1.

There’s also, for all the play’s wisecracking, just something not quite enjoyable in the way Frankie & Johnny romanticizes a man pushing and pushing until he wears down a woman’s resistance. “I see something I want, I don’t take no. I used to but not anymore,” says Johnny, played with nasal Brooklyn brazenness by Shannon, who’s got a fantastic face in the Clint Eastwood vein, the straight slash of his eyes squinting out of geometric slabs of forehead, cheek, and jaw. Johnny’s a short order cook and Frankie’s a waitress. They work together at a greasy spoon, and we meet them mid-coitus in Frankie’s Hell’s Kitchen apartment, where they’ve ended up one Saturday night after weeks of eyeing each other across the order counter. For Frankie — who’s embarrassed about her body and, we learn eventually, has an abusive lover in her past — it’s probably a one-night stand, albeit with very good sex. But for Johnny, “something’s going on in this room, something important.” This woman he hardly knows is, beyond a shadow of a doubt, the One. “This is the only chance we have to really come together,” he insists to the taken-aback Frankie. “People are given one moment to connect. Not two, not three, one! They don’t take it, it’s gone forever.”

Don’t get me wrong: I like a good romance. I have a semi-obsessive relationship with the Merchant and Ivory A Room With a View, which, in its sweeping Edwardian way, features a man telling a woman the exact same thing. But that story unfolds over months, the woman is the true protagonist, and the man’s pushing, while passionate, is also intermittent and not particularly bulldozer-ish. (Even in Burn This, the rip-roaring Pale quietly exits the scene after Anna gives him a hard no.) By making his play a duet, McNally has created a scenario in which Johnny can never really let up on Frankie, even though his declarations of undying-love-plus-eventual-intentions-to-impregnate ebb and flow. It gives Shannon a lot to play: Frankie & Johnny is probably a perennial acting-class favorite — it’s all about tactics. But it also puts the actor playing Frankie in the tiring position of constantly reacting, constantly dodging, constantly negating. And it puts us, the audience, in a weird place: Do we, with Johnny, embrace moonlight and destiny and “the most beautiful music ever written”? Or do we squirm a bit at what’s essentially a play-length version of “no means yes”? Johnny can be right, Frankie really can be working her way toward full expression of her love through a painful past that’s turned her cautious and vulnerable — the specifics can be beautiful, but the discomfort of the general thrust of the action remains.

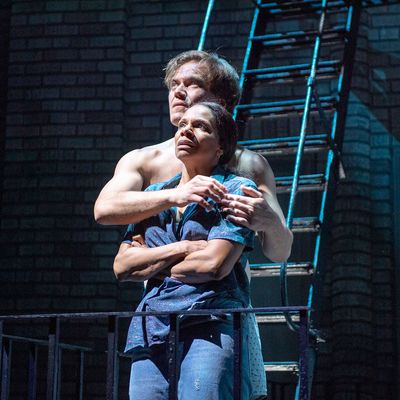

Unsurprisingly, the real treat of this Frankie & Johnny — and perhaps any well-cast Frankie & Johnny — is watching the lively interplay of its two excellent performers. It’s a showcase for actors, and there’s a sweet, off-kilter, earthy chemistry between the down-to-earth McDonald and the hepped-up Shannon. Though Frankie is often nervous when she speaks, McDonald has a way of half-smiling or half-frowning while she listens that gives the sense of a deep, unarticulated inner life. And Shannon — who spends most of the play in boxer shorts, looking gloriously normal-bodied for a big-time actor — smartly leans into Johnny’s oddball qualities and his bursts of childlike enthusiasm. He keeps discovering overlaps in his and Frankie’s habits and pasts (“You’re from Allentown? I was born in Allentown!”), and he leaps on every one with a giddy rush of emotion that delightfully belies his streetwise New Yorker vibe. He’s also both very funny and truly moving in his scruffy affection for Shakespeare, whom he keeps semi-quoting. “I like him,” he muses to Frankie, as if he’s talking about a guy he met at the bar. “I’ve only read of a couple of his things. They’re not easy. Lots of old words. Archaic, you know? Then all of a sudden he puts it all together and comes up with something clear and simple and it’s real nice and you feel you’ve learned something.”

It’s moments like that that keep Frankie & Johnny afloat — the human eccentricities and observations, both little and big. As a play, it’s a reflection of the relationship it depicts: not perfect; at times repetitive, stuck, or awkward; but full of sincerity, hopeful silliness, and emotional innocence. It might show its shortcomings in the light of day, but it looks okay in the moonlight.

Frankie & Johnny in the Claire de Lune is at the Broadhurst Theatre.