The year is nearly halfway up ÔÇö as good a moment as any to take stock of the books that have already made a lasting impression. So far, 2019 has presented us with a wide range of people, places, and stories: a small-town New England candlepin bowling alley across multiple generations; the Great Zambian Novel you didnÔÇÖt know you were waiting for; a mind-bending #MeToo nesting doll of conflicting narratives. If youÔÇÖre looking for something new to read right now, you couldnÔÇÖt do better than the best books of 2019 so far.

If I had a nickel for every book out there that attempts to conjure the magic of a beloved bygone novelist, IÔÇÖd put them in a sock and beat some publisher about the head with it. SmythÔÇÖs part memoir, part critical analysis is an exception to the rule, with a moving portrait of her own fatherÔÇÖs death and a heart-filled understanding of the grief that propelled Virginia WoolfÔÇÖs To the Lighthouse. Read it to conjure Woolf, yes, but also to understand how the stories we read┬ápervade our intellectual DNA and set down roots. ÔÇöHillary Kelly

Being a spy ÔÇö especially for Marie Mitchell, a black woman in New York during the height of ReaganÔÇÖs Cold War ÔÇö is not as glamorous and cutting edge as sheÔÇÖd imagined it would be. ItÔÇÖs not until page 191 of this genre-defying novel, when she is deep undercover in the West African country of Burkina Faso seeking to get information on a charismatic would-be dictator, that Marie gets to operate a cool radio gadget that also works as a camera. Even if her resources are less than high-tech, MarieÔÇÖs journey into the moral and spiritual morass of espionage is inventive. The moral compass in American Spy constantly shifts, and Marie must constantly reevaluate who the good guys are and who the bad guys are. But unlike the heroes of John Le Carr├®ÔÇÖs novels, Marie must also grapple with the cognitive dissonance of serving a country in which she is regarded as a second-class citizen. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

Elizabeth McCracken has a way of adding just the right touch of humor to even the darkest of circumstances, and her prose sparkles with the beauty that comes from mixing the two. Her first novel in 17 years is worth the wait: a big, sweeping saga about a candlepin-bowling alley (Google it if youÔÇÖre not from New England) and the passions and triumphs and tragedies of its owners and patrons over a century. Warning: DonÔÇÖt get too comfortable with any of the characters except for McCrackenÔÇÖs ever-astute third-person narrator. The focus of Bowlaway zooms in and out between blood relations and makeshift families, twisting and tangling the branches of a family tree to limn the connections that both bolster and break us. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

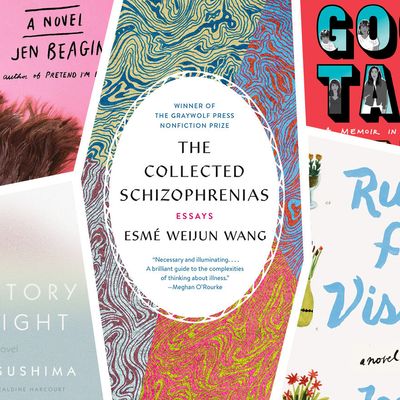

A remarkably clear-sighted look at living with one of the most stigmatized of mental illnesses, Esm├® Weijun WangÔÇÖs essay collection is an impassioned call to see the humanity in people with schizoaffective disorders. Wang is fashionable, sheÔÇÖs well-educated, and she makes both medical and literary references with equal grace. She uses these signifiers to gain the trust of both the people in her life and her readers, to say ÔÇ£I am just like you.ÔÇØ Through her eyes we see that involuntary commitment is a ÔÇ£cureÔÇØ thatÔÇÖs more scarring than the illness is, and that even if youÔÇÖre having trouble distinguishing between reality and fantasy, the fiction of Marilynne Robinson is still safe. In WangÔÇÖs generous telling we are also reminded that those sufferers who are not as ÔÇ£well-adjustedÔÇØ and talented as the author deserve compassion. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

For Mexican writer Valeria LuiselliÔÇÖs last work of fiction, The Story of My Teeth, she sent her story to factory workers, solicited their opinions, and then included their contributions as part of the text. In Lost Children Archive, a road-trip novel turned on its head, Luiselli collects contributions of another kind ÔÇö the stories of children entirely lost, vanished, gone from their families and public attention. More damning than any indictment, this story of a young family searching along the border for a friendÔÇÖs missing refugee children deftly awakens the individualÔÇÖs sense of collective responsibility for the thousands of young migrants floating in political, and existential, limbo. ÔÇöHillary Kelly

ÔÇ£The apartment had windows on all sides,ÔÇØ begins this tiny chiaroscuro of a novel, translated from Japanese into English a full 40 years after its debut, and three years after TsushimaÔÇÖs death. Darkness and light stripe this story of a young motherÔÇÖs first year alone after her husband leaves ÔÇö itÔÇÖs a workaday story of the alternating ecstasy and dread the nameless narrator finds in her new life and her toddler daughter. But as a stylistic and thematic ancestor to Rachel Cusk, Tsushima draws a glimpse of life that will ring uncomfortably true for any parent who subscribes to Jennifer SeniorÔÇÖs theory that parenting is ÔÇ£all joy and no fun.ÔÇØ ÔÇöHillary Kelly

The adventures of a cleaning lady named Mona, whom former cleaning lady and author Jen Beagin first introduced in her debut Pretend IÔÇÖm Dead, continue in this sequel that revels in both order and transgression. (It also stands alone beautifully.) Told in four distinct parts, Vacuum in the Dark throws Mona into different spaces where she cleans, taking the structure of HBOÔÇÖs High Maintenance but with more floor scrubbing. Through it all she talks to her wise imaginary friend Terry Gross, and has a variety of loaded relationships with clients who welcome her into the most intimate parts of their homes and their lives. Occupational hazards abound ÔÇö the first section of the novel is simply called ÔÇ£PoopÔÇØ ÔÇö but Mona also makes art while she works, taking clandestine photographs. When the narrative takes a turn to reunite Mona with her dysfunctional family, the rhythm of the book changes even as MonaÔÇÖs unforgettably wry voice remains throughout. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

This propulsive debut novel follows an unnamed black man who will go to great lengths to shield his biracial son from discrimination in a future America that barely feels far-fetched in its all-encompassing racism. The protagonist risks his happiness, his morals, his relationships, and his pride in order to raise enough money to turn to an experimental surgery to make his son ÔÇ£white,ÔÇØ whether his son likes it or not. We Cast a Shadow is speculative fiction thatÔÇÖs so razor-sharp that its rage is never undercut by its cleverness. If you loved the stories in Nana Kwame Adjei-BrenyahÔÇÖs Friday Black but want to experience something similarly sharp and provocative at novel length, this is your book. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

On the second page of this surly send-up of the makeover-industrial complex, Millie discovers a hole in her underwear ÔÇ£from scratching too much.ÔÇØ Somehow itÔÇÖs downhill from there, as Millie drifts through a series of micro-depressions over her friendless, lonely, crumbs-in-every-couch-crevice kind of life. SheÔÇÖs no Esther Greenwood, though; Millie manages to haul herself out of bed every day to get to the temp job sheÔÇÖs convinced she can turn into a full-time gig, as well as drinks with acquaintances sheÔÇÖs hoping to turn into friends. Alas, this isnÔÇÖt a novel of transformation. It feels as dank and squalid as your worst basement sublet, as it should. ÔÇöHillary Kelly

There are many different threads in this big, lush novel, which follows three families in Zambia over more than a century. In SerpellÔÇÖs artfully rendered world, magical realism exists side by side with historical fiction and science fiction but no section of the book feels overwritten; all of the grandness of her storytelling feels well-earned. And when SerpellÔÇÖs smashing together of genres leads to the inevitable moment when disjointed story arcs collide, the explosion feels like nothing less than destiny. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

In an attempt to answer all of her young sonÔÇÖs questions about race and identity and Michael Jackson honestly, Mira Jacob had a series of earnest and funny and often uncomfortable conversations. The result is this vulnerable yet wise graphic memoir, informed by JacobÔÇÖs own experiences as an Indian-American woman and the current political moment, in which so many questions feel unanswerable even to ourselves. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

I canÔÇÖt and wonÔÇÖt stop recommending this remarkable, genre-collapsing novel to any and all friends. Choi, whose prior work tended toward the lyrical and discursive, has changed her tack and written a minutely precise story that will rivet you sentence by sentence. ItÔÇÖs the defining novel of the #MeToo era ÔÇö the story of a failed high-school relationship, contested sexual interactions, and a variety of women wrestling over collective memory. If all that sounds too abstract, know that every page brings a new gut punch for any woman who has ever felt trapped inside her own story. ÔÇöHillary Kelly

The true events that inspired Women Talking are monstrous: In 2009 it was revealed that female members of a Mennonite colony in Bolivia had been drugged and raped in the middle of the night by men in their community. Toews does not focus her stunning novel on the horror of the crimes perpetrated on these women as much as she does on the aftermath. She takes us inside a secret meeting, as the women grapple with faith, justice, and loyalty in the face of ultimate betrayal, deciding whether or not to leave the colony for good. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

When Midhat Kamal is sent from his homeland of Palestine to study medicine in Montpellier, France, he canÔÇÖt know that in just a few short years World War I will first upend his new French life and render his hometown of Nablus into a pawn of escalating regional skirmishes. The scope of this novel is ambitious ÔÇö almost 600 pages of detailed local Palestinian politics, geography, and lore ÔÇö but Hammad, at 27, has packed it chock-full with every vital ingredient of a sweeping classic, including a lush, fully alive protagonist. Set aside a few long afternoons. ÔÇöHillary Kelly

Harper Lee was both more ambitious and more complicated than her millions of readers give her credit for, as Cep reveals in this investigation of the true-crime story that the author of To Kill a Mockingbird so ardently wanted to write. Cep first traces the case of a reverend in 1970s Alabama who was accused of murdering five family members for insurance money ÔÇö and shot dead by a vigilante at one victimÔÇÖs funeral. Then she probes Harper LeeÔÇÖs own fascination with the story, and the ways in which she tried to fashion it into what could have been her second masterpiece. ÔÇöMaris Kreizman

It sounds like a quaint little book: a single, socially isolated gardener goes on a quest to visit old friends and reconnect with the world, finding peace and love along the way. But from its first line ÔÇö ÔÇ£Midway through my fortieth year, I reached a point where the balance of the past and all it contained seemed to outweigh the future, my mind so full of things said and not said, done and undone, I no longer understood how to move forwardÔÇØ ÔÇö I was convinced that KaneÔÇÖs understated meditation on loneliness in the digital age was just the right kind of narrative, an antidote for our distracted days. ÔÇöHillary Kelly

Every editorial product is independently selected. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.