We’re nearing the end of another year, which means movie season is truly kicking into gear. Sure, the first few months of 2019 gave us some gems: a politicized zombie slasher (Us), a Swedish vacation turned living nightmare (Midsommar), the return of Quentin Tarantino (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood), an Obama-produced Netflix doc (American Factory), Brad Pitt in space (Ad Astra). But October was when the cinema truly arrived, bringing us an acid black comedy from Bong Joon Ho, a followup from The Witch director Robert Eggers, and the return of Eddie Murphy. With that in mind, here are the best movies of the year that Vulture has reviewed, according to David Edelstein, Emily Yoshida, Bilge Ebiri, Angelica Jade Bastién, and Alison Willmore.

(A quick reminder about our methodology: We’ve restricted this list only to films that have had an official release in the first 10 months of 2019. For a complete list of the top 10 films of 2019, sorted by critic, read our year-end roundup here.)

Arctic

Enjoyable and excruciating. In Joe Penna’s survival drama, the riveting Mads Mikkelsen plays a man whose plane has gone down in the frozen wilderness. That’s all we know about him and all we really need to — it’s what he does and keeps doing that defines him. Thrown together with a grievously wounded, non–compos mentis woman, he tugs her well-swaddled form on a sled into the unknown, trudging and grunting and falling and trudging and heeeaving and trudging and heeeaving — and just when we think it can’t get more horrible, we realize that up until then he’d had it easy. The movie really takes your mind off your own troubles. —D.E.

Birds of Passage

Set in the north of Colombia among the indigenous Wayuu, Ciro Guerra and Cristina Gallego’s knockout film is part ethnographic documentary, part The Godfather. Over 20 years (from 1960 to 1980), people whose ways first seem strange metamorphose into a familiar breed of narcos, moving tons of marijuana, and become avid materialists. As in Guerra’s last film, Embrace of the Serpent, the disjunction between ancient ways and modern, ephemeral fashions and technology is not just jarring but toxic, a shock to the system that will almost certainly kill the host. The drive toward revenge kills the characters long before anyone dies. It kills their souls. —D.E.

Escape Room

Escape Room didn’t need to be good, and its release during the very first week of the year seemed destined to make it a 2019 B-movie footnote. But the ensemble thriller from Insidious and Paranormal Activity vet Adam Robitel is a whole lot of fun, throwing a group of strangers together into a hyperbolically lethal version of the titular team-building game. It’s much more of a puzzler than it is a horror film, and Robitel doesn’t need gore or jump scares to keep the whole thing tightly wound. The grand finale is so audacious that you’ll be ready to buy a ticket for the sequel before the lights come up. —E.Y.

Fighting With My Family

The unlikely collaboration between writer-director Stephen Merchant and executive producer the Rock is an unexpected joy — a true story that skips along its inspirational sports-movie template while finding real pathos and tough truths under all that sparkly spandex. As WWE champion Paige, Florence Pugh is equal parts ferocious and tender, a misfit struggling to find the right way to share her talents with the world. It’s a WWE production, but if it’s propaganda for the sport, it’s the kind you’ll gladly let win you over to the joyful absurdities of the sport. —E.Y.

Transit

Director Christian Petzold (Barbara, Phoenix) changes the time of Anna Seghers’s 1944 novel, in which refugees from the Nazis stuck in Lyon wait for ships to North America: It’s still Lyon, but the period trappings are gone and they’re now fleeing all-purpose “fascists.” At the heart of the story is a slow-motion mistaken-identity farce in which a concentration-camp escapee, Georg (the charismatic Franz Rogowski, who bears a resemblance to Joaquin Phoenix), assumes the identity of a famous writer whom only Georg knows committed suicide — and then falls madly for the writer’s discombobulated wife (Paula Beer). The physical, temporal, and emotional geography is very confusing, but the film is still potent. Petzold is part acrid realist, part romantic: His protagonists lose everything but their passion, emotion being the last refuge. —D.E.

Climax

It’s Step Up crossed with Battle Royale, a house-music Suspiria, and exactly as fun and harrowing as that description would suggest. French adulte terrible Gaspar Noé (Enter the Void, Love) brings together a vibrant ensemble of dancers led by dynamo Sofia Boutella for a party gone horribly awry thanks to some no-good sangria. In what feels like more-or-less real time, we watch a cohesive, unified group of very-much-alive young people devolve into screaming, hallucinatory chaos, all set to an incredible disco-techno soundtrack. Noé’s desire to shock is still ever-present, and all trigger warnings still apply. But the dizzying, acrobatic camerawork and the impressive physical and emotional work of Boutella and the rest of the cast make this his most crowd-pleasing — dare I say, even sentimental? — work yet. —E.Y.

Diane

A stunning platform for Mary Kay Place as a compulsive do-gooder out to expiate her sins as everyone around her is either dying (a first cousin with end-stage cervical cancer) or on the brink (her addict son and a slew of elderly friends and relatives). Kent Jones’s drama — mostly naturalistic, but with the odd expressionist flourish — is generally regarded as one of the most depressing ever made, but once you accept its un-transcendent, death-centric baseline the movie is strangely exhilarating. In between scenes are shots taken through a windshield of rural landscapes passing in every season, with soft, haunting music by Jeremiah Bornfield, with the film’s protagonist (like all of us) going from someplace to someplace on the road to who-knows-where. In its mundane way, Diane shows you glimmers of the sublime. —D.E.

The Brink

Alison Klayman’s On the Road With Steve Bannon doc is essential, sad to say, given that Bannon is not a fringe hate-monger but a man with the ears of protofascist, xenophobic movement leaders in the U.S., France, Belgium, Hungary, Germany, and the U.K., as well as sundry billionaires. Why would Bannon let Klayman be a fly on his wall — or in his ointment? He has faith in his message. He already has “a solid enough minority that’s immoveable.” He just needs to sway an increasingly susceptible 15 percent of the rest, and he’s excellent at making people feel as if they’re being marginalized by a dark (in all senses) cabal — while he denies and denies and denies that he’s saying what he in fact is. Klayman doesn’t have to editorialize to make the point that Bannon is one of the most dangerous people alive. —D.E.

Ash Is the Purest White

Jia Zhangke’s epic revisits many of the themes he’s explored throughout his past few films (Mountains May Depart, A Touch of Sin), particularly the near-absurdities of a rapidly changing modern China, and it’s as profoundly wrought as ever. With Ash, however, there’s a genre twist; a sort of pulp gangster romance shot through Zhangke’s patient, wide lens. A deceptively steely Zhao Tao stars as a woman separated from the man who, for better or worse, is the love of her life, and sets out to find her way back to him over two and half decades. It’s as much a story of a country rebuilding itself as it is of one woman doing the same, and by its gutting resolution you’ll feel as if you’ve walked those miles and years in Zhao’s shoes. —E.Y.

Us

A politicized zombie-slasher film in which subterranean doppelgängers — separate but mystically “tethered” to their aboveground analogs — swarm our world with scissors and the message, “We exist.” Once you get over the disappointment that Jordan Peele’s second feature isn’t as trim or impish in its satire as his marvelous debut, Get Out, you can settle back and salute what it is: the most inspiring kind of miss. It’s what you want an artist of Peele’s sensibility and stature to attempt — to broaden his canvas, deepen his psychological insight, and add new cinematic tools to his kit. Fans will rewatch the film to savor the fillips, the purposeful echoes, and the “Easter eggs,” as well as a dual performance by Lupita Nyong’o that’s otherworldly in its brilliance. As the double, “Red,” she adopts a voice that’s the whistle of someone whose throat has been cut, with a gap between the start of a word in the diaphragm and its finish in the head. It’s like a rush of acrid air from a tomb. —D.E.

Amazing Grace

Over two nights in 1972, Aretha Franklin, then at the height of her fame, came to Los Angeles’s New Temple Missionary Baptist Church to record a selection of gospel classics. The resulting album, Amazing Grace, was one of the most acclaimed of her career. Director Sydney Pollack documented both nights with a small array of 16 mm cameras, but the footage languished for decades until producer Alan Elliott bought it and put together this concert documentary, which was then further delayed by Franklin’s own, somewhat surprising refusal to let it be shown. But now it’s here, and it is transcendent. Resplendent in her caftans but otherwise humble, Franklin gives off no diva or rock-star airs. But as soon as she starts singing, she’s in — eyes closed, head up, half-grins turning into flights of ecstatic joy. So is her audience, shouting their support, cheering her along, dancing in the aisles. And so are we. The movie itself feels like a church service, and it’s enough to make you get religion. —Bilge Ebiri

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

Terry Gilliam’s notorious film maudit, three decades in the unmaking and already the subject of a 17-year-old documentary about the collapse of its production, is, uh, here. And it’s surprisingly light on its feet. The story follows a slick commercial director (played by Adam Driver, an inspired choice) who returns to the Spanish village where he made his thesis film ten years ago, an adaptation of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and discovers that the lives there were ruined by his production. Reuniting with the aging cobbler who played his Quixote (Jonathan Pryce), he discovers that the man still imagines himself to be the 17th-century knight-errant. Their ensuing journey mixes medieval gallantry, contemporary topicality, and typically Gilliamesque chaos — a swirling vortex of disguises, dream visions, broad humor, and a delightfully disorienting look at both the creative and destructive power of imagination. —B.E.

Trial by Fire

Murderously hard to sit through, which is not something you’ll see on top of an ad. Maybe that’s why the film had been a commercial bust. But this portrait of Cameron Todd Willingham (Jack O’Connell), a Texas ne’er-do-well executed for burning his three little girls to death, is painstakingly well-made and important. The director, Ed Zwick, isn’t cynical about the motives of the investigators who allegedly screwed up so badly in interpreting the evidence. The lie of most police dramas isn’t that they’re on the side of the angels — it’s that they’re always competent at what they do and that there are fail-safe mechanisms to keep innocent people from the death chamber. Laura Dern plays the divorced mother who volunteers to be a pen pal to someone on death row and gets sucked in when she reads the trial transcript. Dern is a great detective actress — she externalizes thought. —D.E.

The Souvenir

A coolly intelligent autobiographical film by the British writer-director Joanna Hogg, who doesn’t often give you your narrative bearings — and spoils you for over-shapers, the spoon-feeders. Her protagonist (Honor Swinton Byrne, daughter of Tilda, who plays her mother onscreen) is a well-off, socially conscious 24-year-old film student who wants to make a movie about a boy growing up by the grotty docks near Newcastle but is thrown off course by her foppish, madly pretentious, and (as it turns out) heroin-addicted boyfriend (Tom Burke). At times the film seems too distanced, but it’s never obvious or banal. Hogg convinces you that incoherence is the only honest way to tell a story with any emotional complexity. —D.E.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco

The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a testament to the power of human touch. Actor Jimmie Fails and director Joe Talbot’s semi-autobiographical debut is a gorgeously wrought love letter to the city. The film follows Jimmie Fails (the character bears the name of the actor) as he fights to reclaim and tend for the home his great-grandfather built, going so far as to squat in the Victorian house with his artist friend Montgomery (Jonathan Majors). But his obsession with the home is based on a long-held lie; Jimmie’s grandfather didn’t actually build that house. Visually, the film is brimming with painterly tableaus of black life. It powerfully considers black masculinity as performance through a Greek chorus of men that veer in and out of Monty’s and Jimmie’s lives, but the movie’s real potency derives from how it ponders the way geography acts as identity. Home is where our most deep-seated wounds lie. In the end, the crown jewel of the story is the tender, curious, and empathetic performance by Majors that’s continued to haunt me for weeks. —Angelica Jade Bastién

Midsommar

Grueling, grisly, and full of white people wearing white in the Swedish summer solstice, Ari Aster’s follow-up to the supremely un-fun Hereditary has a similar theme: the allure of an alternate family with clear-cut values. In this case, it’s now a cult of radiant pagan Swedes who believe themselves in harmony with the natural world, who represent something harshly beautiful to the bereft American protagonist, Dani Ardor (the superb Florence Pugh). The most ambitious horror blurs the line between the psychological and the mythic, between ordinary human emotions and symbol-laden Blakean nightmares, and Aster is very ambitious and very blurry. But the blurriness is unnerving, the finale both horrific and strangely beautiful. —D.E.

Wild Rose

Harsher and less formulaic than most Go-For-It movies, this story of an unstable, ex-con Glaswegian single mother named Rose-Lynn who longs to sing country music (not country-Western, she will hiss) is a great pedestal for the chameleon Irish actress Jessie Buckley. Buckley (who got her start in musical-comedy) has a first-class voice for country, with warm, slightly ragged chest tones that make the leap to high soprano with just a touch of effort, so that you feel the cost to the singer as well as her triumph. Directed by Tom Harper from a script by Nicole Taylor, the movie turns on whether Rose-Lynne (who longs to leave Glasgow and her family for Nashville) can be a proper mom to her two small children — which is also the key to deepening her artistry. With Julie Walters as Rose-Lynne’s suffering mother and a cameo by the BBC 2 country DJ “Whispering” Bob Harris, who gently presses her say something personal with her songs. —D.E.

Domino

A thrilling return to form for Brian DePalma — but also under-funded, shorn of nearly half its director’s intended running time, and occasionally ludicrous. The convoluted, right-wing-ish story centers on two Danish cops: Christian (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, between seasons of Game of Thrones) and Alex (Carice van Houten, ditto) on the hunt for a Libyan immigrant (Eriq Ebouaney) who killed Christian’s partner, who was also Alex’s illicit lover. What they don’t know is that the Libyan is being protected by the CIA (led by Guy Pearce), which tacitly approves of his locating, torturing, and killing ISIS operatives to get to the sheikh who murdered his father. What keeps you entranced is De Palma’s pacing. In the key sequences, the action slows to a crawl — proof that the greatest suspense comes from helplessness in a world where you can see what’s coming but can’t think or move fast enough to forestall the horror. —D.E.

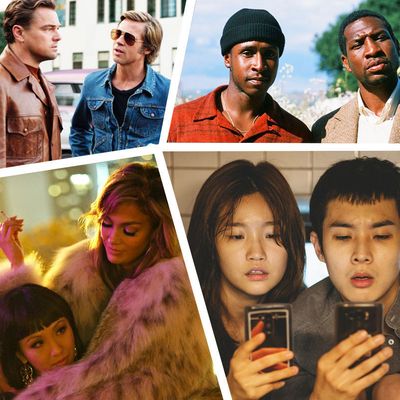

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Quentin Tarantino’s tenth film — starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Rick Dalton, a fading, alcoholic Western TV star and Brad Pitt as Cliff Booth, his loyal stuntman, driver, gofer, and one-man entourage — is a pastiche of ’60s pop culture that transcends its inspirations: It’s a farrago of genius. It plays as a series of entertaining digressions until its convulsively brutal climax, in which members of the Manson family approach the home of Rick’s neighbor Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) for what we know going in will be the massacre that symbolically ended the hippie utopia. Has there ever been a finale simultaneously so euphoric and heartbreaking? Tarantino’s dream world is a sadistic place, but in a way it’s sublime, a heaven nestled inside hell. (Star-making turns: the lithe Margaret Qualley as a Manson girl and little Julia Butters as an endearingly serious child actress who penetrates Rick’s shell of alienation.) —D.E.

Crawl

Crawl is a great example of a simple story exceedingly well-told. It’s a bloody adventure full of teeth-gnawing turns of fortune, mordant wit, vicious gator kills, and surprising tenderness — that clocks in at a blessedly fleet 87 minutes. It’s a perfect horror film for the summer, as much an ode to the cataclysmic, humbling aspects of Mother Nature as it is a love letter to father-daughter relationships. The latter dynamic provides the film’s tender through line, keeping us invested in the survival of the only main characters in the movie. Some of the most fun I’ve had in the theater this season was watching Haley navigate creature-infested waters, balance trepidatiously on the sink as the waters rise, or with teary-eyed regret create a tourniquet for her gnawed thigh. Scodelario is great at communicating various levels of pain and discomfort as she traverses gross, grimy small spaces in order to survive. Crawl is a gut punch in cinematic form, a grimy ode to the Floridian environment, but none of it would work without her transfixing performance. —A.J.B.

Firecrackers

In the bang-up debut by Jasmin Mozaffari, high-school grads Lou (redhead Michaela Kurimsky) and Chantal (Karena Evans) make strides to escape their rundown town and poisonous families. But the danger is everywhere, not just from predatory males but from themselves: They’re of this culture and susceptible to it, no matter their smarts and resolve. Mozaffari dramatizes the illusory nature of control. Lou and Chantal have some but not a lot, and often the ways in which they try to get it back tightens the vise. You come away from marveling not at their strength but at their nonending struggle against weakness. —D.E.

For Sama

Deaths of children are the heart of Waad Al-Kateab and Edward Watts’s first-person documentary of the 2016 siege of Aleppo — Sama being Waad’s baby daughter, whose existence haunts Waad as she films her husband, Hamza (one of the few doctors remaining), as he attempts to save yet another bomb-mangled child. Much of the film takes place inside the hospital where Hamza will do 890 operations in 20 days, but it doesn’t feel like raw footage — it has been carefully shaped. Watching the film, you feel it would be an act of cowardice to look away from even the most tragic sights. It’s not propaganda but a mother’s plea to bear witness. —D.E.

Marianne & Leonard

Marianne is Norwegian single mother Marianne Ihlen, whom Leonard Cohen immortalized in the loving breakup song “So Long, Marianne,” after a relationship that began in the ’60s in a period of creative ferment on the Greek island of Hydra. Nick Broomfield’s documentary tells the stories of both Marianne and Leonard, though much of what Leonard says (in interviews and footage spanning half a century) is about Leonard and much of what Marianne says is about Leonard, too. Cohen emerges as a great artist and a limited man who admits that a large part of his life was about escaping from other people. But you still end up — especially when he performs — in his thrall. He reaches out to Marianne on her deathbed, telling his “old friend” that he won’t be far behind (he wasn’t) and wishing her “safe travels down the road.” —D.E.

Official Secrets

The Brits do low-key, paranoid procedural dramas like this one so well, with a pervading chill and no flash. It’s set in 2003 and 2004, before and after British intelligence analyst Katharine Gun (Keira Knightley) leaks a memo from the U.S. directing her agency to dig up dirt on members of the U.N. Security Council, to help “persuade” them to authorize the invasion of Iraq. To determine the memo’s authenticity, reporters led by Matt Smith and Matthew Goode have furtive meetings in clubs and on tennis courts with men who know something or know someone who knows something, while director Gavin Hood channels Alan Pakula with shots that suggest that someone’s always watching. Ralph Fiennes plays the unemotive barrister who takes Katharine’s case: One of the film’s chief pleasures is seeing his faint quarter-smile as he tells her she’s done good. —D.E.

One Child Nation

Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang’s first-person documentary chronicles the effects of China’s one-child law in infuriating, tragic, and grisly detail. It turns out that the 1985 policy ushered in (with cheerful, propagandistic songs, posters, and Chinese “operas,” many on display) an ongoing totalitarian nightmare, the scale of which is rarely appreciated outside the so-called People’s Republic. You see trash heaps with bodies of infants sticking out of medical-waste bags and men and women still broken by the memory of forced sterilizations — or, worse, abandoning baby girls to die. A child born in the middle of the policy’s implementation (it ended in 2005, when China found itself with a severely denuded next generation), Wang muses on the connection between governments that mandate abortions and those that prohibit it: Neither gives freedom of choice to the woman over her own body. —D.E.

American Factory

An expansive, humanistic documentary set largely in Dayton, Ohio, where a closed GM plant is reborn as a Chinese-owned windshield factory, Fuyao Glass. Steve Bognar, and Julia Reichert’s film is incisive (sometimes hilarious) in depicting the culture clash between stubbornly individualistic Americans (slow, with “fat fingers,” according to Chinese executives) and ultradisciplined, anything-for-the-company Chinese workers. But the underlying story is grim: The Chinese idea of human workers as machine parts will yield soon enough to actual machines doing all the labor. It’s the worst of communism (become a cog, a zombie drone) combined with the worst of free-market capitalism (you’re expendable in all ways). This is the first Netflix film released under Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground banner. Too bad you can’t see it in a theater. —D.E.

Hustlers

Hustlers is simply magical. At once a sincere exploration of female friendship and a glorious evisceration of capitalism, Hustlers challenges and dazzles in equal measure as it tracks the story of Destiny (a moving Constance Wu), a stripper who, alongside a gallery of friends, starts drugging men in order to gain unimpeded access to their credit limits. Lorene Scafaria’s writing is endlessly quotable, with lines like “Drain the clock, not the cock!” rooting themselves in your memory. Her direction, meanwhile, exalts the female form, allowing for memorable turns by Wu, Keke Palmer, Cardi B, and Lili Reinhart. But Jennifer Lopez is the film’s towering crown jewel. Her leonine grace and cunning delivery reveal new grooves in her character Romana’s vibrant, multifaceted persona. Brimming with glittery excess and a sincere celebration of women’s autonomous selves, Hustlers is one of the most beguiling films of the year. —A.J.B.

Ad Astra

James Gray’s space opera Ad Astra is so eerily, transfixingly beautiful that I want to purge from my mind its resolution, which reduces what precedes it to a Shaggy Dad story — an especially earthbound one. In outline, the film is a Kubrick-like retelling of Apocalypse Now in which the Willard character, Roy McBride (Brad Pitt), is the son of the renegade Kurtz figure, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), whose ship disappeared many years ago (this is the “near future”) in the vicinity of Neptune while searching for signs of distant life. Roy is a great role for Pitt, who narrates throughout in a measured, groggy voice reminiscent of Martin Sheen and whose lack of modulation can thereby pass for existential woe. The cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema’s frames are spare, evoking the vast distance between souls. The effect is to make you understand the pressure not to feel — and hence to experience, with Roy, a fierce longing for the material world. —D.E.

One Cut of the Dead

This Japanese horror comedy is part zombie flick, part love letter to low-budget filmmaking — and when those two things converge in its last act, it’s also just about the most joyous thing you can experience at the movies this year. Shin’ichirô Ueda’s movie was made on the supercheap itself, gathering critical acclaim and building word of mouth by touring film festivals around the world until it was rereleased back at home to become an unlikely indie hit. But while One Cut of the Dead is a marvel of ingenuity, both in terms of its characters and its own construction, what really impresses is its heart — and the genuine affection it has for putting on a show, even when that show involves having to do a lot of blood-soaked improv because nothing is going to plan. —Alison Willmore

The Laundromat

A colleague has referred to The Laundromat as a “poor man’s The Big Short.” I would correct that to a “heavily mortgaged middle-class man’s The Big Short,” and add that that is not such a bad thing. The movie is convoluted — as befits its subject — but breezy and fun and engaging enough to make you want to investigate further, especially if you have money to squirrel away. (I kid!) As his own cinematographer, under the name “Peter Andrew,” Steven Soderbergh winds up his actors, points them in the general direction he wants them to go, and follows along eagerly, as if discovering the subject along with the rest of us. Screenwriter Scott Z. Burns’s stroke of brilliance is in making the villains of the story our loquacious hosts. His broad agitprop comedy is labored in parts but is, as a whole, sensationally valuable. —D.E.

Monos

It’s easy to compare Alejandro Landes’s lush child-soldier saga to Lord of the Flies, but the truth is that Monos feels like it’s more about the fever dream of adolescence than it is about civilization crumbling out in the wilderness. Its eight guerrillas (most of whom are first-time actors, not including Hannah Montana alum Moisés Arias) may be armed and in charge of guarding an American hostage, but they’re also teenagers who fool around recklessly, harbor romantic jealousies, and react with wild impulsivity to the prospect of consequences. Monos doesn’t give context to the conflict its characters are involved in, because it’s the personal dramas that seem to loom much larger in their lives anyway, especially when things start going wrong. The film envelops the audience in the sensory details of the lives of these kids playing at being revolutionaries out on a mountaintop, presenting a world that seems equal parts paradise and hell. —A.W.

Parasite

Bong Joon-ho’s acid black comedy centers on a down-and-out South Korean family that insinuates itself into the household of a rich one. For a while it seems like a clever but essentially one-joke movie — until the bottom falls out of the joke, metaphorically and literally, to reveal an underclass under the underclass and a society built on sweeping things way under the rug. Thereafter, Bong leaves social realism far behind and moves into horror movie territory — haunted houses, pop-up skeletons — and then farce and then tragedy. Who are the real parasites? The poor who attach themselves to the rich or the rich who suck the marrow of the poor? Or is the system itself the parasite, drawing its energy from the turbulent interaction between rich and poor? The central metaphor eats into the mind. —D.E.

Pain and Glory

Pain and Glory is at once the gentlest and most emotionally naked movie Pedro Almodóvar has ever made. It’s somewhat autobiographical — as the aging filmmaker and onetime provocateur Salvador Mallo, the wonderful Antonio Banderas has been outfitted with Almodóvar’s colorful shirts and high-tops, as well as his shock of happy hair — and its mazelike narrative weaves in and out of the past, as its protagonist looks back on his lost loves, his sexual awakening, and his angelic mother’s efforts to give him a better life. Throughout, the film seems to be saying something about the communal, almost supernatural power of art: Salvador is a man paralyzed both creatively and emotionally, and yet creation swirls around him. An early film, now regarded as a classic, is given a restoration and screening. A stray composition about a long-lost boyfriend becomes a monologue that then prompts a remarkable and tender reunion. A supposedly anonymous painting drifts back unexpectedly into his life, prompting a cascade of memories, a reminder from the universe that art is meant to be sent out into the world, not kept hidden away. The film itself is one of Almodóvar’s greatest gifts to his audience, and it all leads to a closing shot that may very well leave you a wreck. —B.E.

The Lighthouse

You won’t find a finer black-and-white freakout this year than Robert Eggers’s claustrophobic follow-up to his 2015 banger The Witch. Willem Dafoe is saltier than a bag of chips as a garrulous lighthouse keeper who may or may not have murdered his former co-worker. Robert Pattinson broods and scowls and fantasizes about fucking a mermaid while shouldering more than his fair share of the hard labor as the junior of the two wickies. The dialogue’s delicious and the period details have an impressive tangibility to them, but what really makes the movie work is something timeless — the feeling of being stuck in close company with someone you can’t always stand, but can’t ever get away from. —A.W.

Dolemite Is My Name

Everything clicks in this breezy, ironic biopic starring Eddie Murphy as Rudy Ray Moore, who arrested a midcareer fade-out in the 1960s by developing an alter ego called “Dolemite,” a pimp, libertine, and fabulist with roots in black American folklore. Directed by Craig Brewer from a script by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, the movie has the buoyant, let’s-put-on-a-show feel of Alexander and Karaszewski’s Ed Wood, which also celebrates self-actualization over actual talent, dignity well lost for the sake of fame. Murphy is in clover showing Rudy Ray build Dolemite from scratch: Is there anything more rewarding for a great clown than nailing a character, making it seem as if that character has always existed in the ether, waiting for a genius to set him free? —D.E.

Synonyms

Yoav, a young Israeli man, arrives in France with hopes of assuming a new life. He hopes never to see Israel again, refusing even to speak Hebrew anymore. He wanders the streets repeating French words and phrases to himself, trying to will himself into a new identity. He has stories — vague ones — about his life and his disturbing experiences in the Israeli military, and we sense his rage and desire to break free. The film is based loosely on director Nadav Lapid’s own experiences, when, in his early 20s, not long after completing his military service, he fled to France, only to discover that, as he put it once in an interview, “I’ve never felt myself so Israeli as when I was in Paris.” And so, Synonyms is a movie about how inescapable our identities are, as Lapid finds a fascinating stylistic correlative with which to illustrate the protagonist’s sense of cognitive, corporeal entrapment. But for all the artful obliqueness of the director’s style, with his elliptical narrative and bemused, deadpan mood, the autobiographical background of the story also lends it a lived-in honesty; the incidents and interactions feel both symbolic and true. —B.E.