Looking for some quality comedy entertainment to check out? Who better to turn to for under-the-radar comedy recommendations than comedians? In our recurring series Underrated, we chat with writers and performers from the comedy world about an unsung comedy moment of their choosing that they think deserves more praise.

“Underrated” is a chance for comedians to share hidden gems with the Vulture audience. But Tim Heidecker loved the “Cory and Brendan” videos so much that he started developing material with them. When you have a production company and like something, you kind of have to put your money where your mouth is.

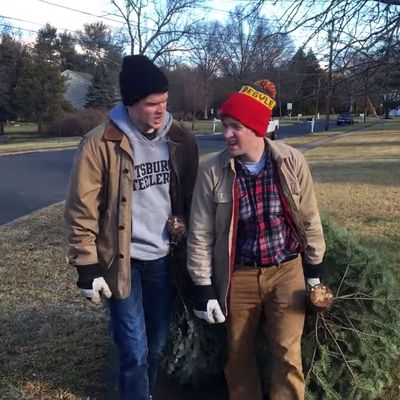

Brendan O’Hare and Cory Snearowski perform in videos directed by Daniel O’Hare and shot in their native Branchburg, New Jersey. Branchburg is the exact midpoint between New York and Philadelphia. There is literally nowhere more suburban. In the videos (and now podcast produced by Abso Lutely), O’Hare and Snearowski play angry baseball dads, small-town mayors, and barbers who only work on the side of highways.

The absurd humor plays out on a bleak, flat Jersey landscape. That was one of the things that drew Heidecker — that the aesthetic matched the humor so perfectly. Heidecker’s work often blurs the line between parody and sincere homage, including his new album out today. What the Brokenhearted Do … is a breakup album in the style of Son of Schmilsson — a yachty tale of the divorce QAnon is convinced Heidecker has gone through. We talked with Heidecker about Branchburg, the absurdity of small-town mayors, and how online is too online.

How did you come to find out about Cory and Brendan?

I think it was through Vic Berger. He posted on his Facebook; I think it was the “Christmas Tree” video. And I watched it and loved it.

What did you love about it?

I liked a lot of things about it. I liked the environment that they put themselves in. Living in California but coming from the East Coast, I really identified with that bleak suburban New Jersey winter — them trudging through these plain-looking neighborhoods with cookie-cutter houses. Also, their writing is good. I think there’s a lot of funny people, or people who think they’re funny, who think they can tie a bunch of non sequiturs together and improvise to create an absurd conversation. But theirs had a thoughtfulness to it. There were some surprises to it. They were just both very likable right away, too. The whole thing felt kind of timeless.

One of the little non sequitur asides is that one of them is the brand-new mayor.

[Laughs.] Yeah.

And that the old mayor named every single road after Malcolm X and he has to go fix that.

I like that civic, municipal awareness. It reminded me of Tom Goes to the Mayor a little bit: local government, people being involved in the minutiae of their township.

“Mayor” is such a funny job to have because it’s almost enough power. But it’s also so small.

Yeah, I think there’s a lot of comedy to draw from that. Especially when it comes to these sort of quasi-towns that don’t have a lot of identity to them. Like, what do they do? I’m sure they do a lot, though.

Something that I really liked about that video was the way their relationship is left so vague. It made me think about how dudes use small talk to hide the fact that they are complete strangers.

Yeah. I picked up on that, too.

A lot of your work can be seen as a deconstruction of a certain type of toxic male.

Yeah.

Would you consider your character in Us to be part of that?

Oh, yeah, I guess so. There’s an entitled and comfortable quality to that character that we talked about. It doesn’t get a lot of time to develop in the movie, but it’s there. The digital release has outtakes that further amplify that.

How did Abso Lutely get involved with Cory and Brendan?

As a production company we’re always on the lookout, scouting talent and people that sync with our vibes. So I reached out. I said, “We’d love to see what we can do to help you guys.” It started from that. The one thing we could do was get them just a little more money so that the production value of the work increases just a little bit. So the audio is a little better and you’re not just shooting it on your iPhone. I didn’t want to start sending them out into meetings with just those videos because the lo-fi quality would turn some people off. But I didn’t want to lose the intimate feel, like the stuff that Eric and I used to do. So for the next year or so we kind of funneled them a little development money and said, “Go and make more stuff.” And that’s what they did.

And then whose idea was it to start the podcast?

It was mine. At some point, we had the Branchburg pilot that we used to sell them around town. But everyone was still feeling like these guys were a little too young, too weird. And the environment for that on cable right now — for the moment, everyone feels a little risk averse. They’re not super excited to try weird comedy.

Not long ago, my manager made a good point that podcasts are now what Adult Swim was ten years ago. It’s a place where, for almost no money, you can experiment, you can develop your voice, you can find an audience.

Let’s talk a little bit more about the Branchburg aesthetic. I’m from an extremely flat part of Indiana, and it reminded me so much of all the snow-covered soybean fields I had to walk across to get drunk as a teenager.

I’m the same way. I grew up in Allentown, in a lot of development and fields. When we first started talking to them, they asked, “Should we come out to L.A.? If we’re going to shoot something, where would we shoot it?” So much of the tone that I see in them comes from the environment. I don’t see it on TV either — the suburbs done the way they shoot them. I was like, “You’ve got to shoot it in your hometown, and you’ve got to shoot it in the winter because I want to see you cold in coats and feeling that. No leaves on the trees.” That was one of the things I really loved about them. It was something I hadn’t seen. Maybe in Welcome to the Dollhouse.

In the video that y’all produced, they use this clothing-donation bin that seems to be in the middle of nowhere. There are no buildings in the frame.

Yeah, I liked the vibe of these guys as pedestrians having to live in this environment not made for pedestrians. You’re constantly encountering highways and impassable interchanges, distances of fields to get places. I think it amplifies the struggle that those guys put themselves in and the absurdity of [the suburbs] — this community we’ve created for ourselves that can be very comfortable but very isolating.

Is the look of DIY important to you, or is it that people are most free to create when there are no stakes and no budget?

There are some things that deserve to be lo-fi, and that’s part of the joke. If you’re going to do an old local commercial or cable-access kind of bit, it’s really appropriate for it to feel lo-fi. But I felt that their work didn’t necessarily play to that. With better gear, you could tell their stories similarly. It would capture their environment better. These guys know how to frame, how to direct, they just didn’t have the gear. But you don’t want to slow things down, bog it in a bigger production.

That’s something that I’ve always appreciated in your work — that you match the aesthetics to the comedy. Trying to find which tone works. On your new album, it feels very Harry Nilsson–y.

Thank you. It’s the kind of music I love, and I don’t think I can make anything else. I try to do my best version of it. It’s all I can do.

What exactly inspired you to write a breakup album?

A few things. Partly just that I like those kinds of records. I like sad songs. I’ve had my own experiences with breakups. Not necessarily always romantic breakups, but changes of life in various forms. On a more comedic level, I was in the trenches with the internet trolls for the last few years. They used this rumor that my wife had left me because of my anti-Trump protest. They had gone so far as to doctor up divorce papers and put it up on 4chan. It became this weird burn that they would use at me. Like, “Oh, is that why your wife left you?” I was writing these songs that were going in a certain direction, [and] I thought, Oh, this is a nice way to frame it. Maybe feed them a little bit with it.

It’s not autobiographical. People are like, “Is this a joke? Is this a meta thing?” But a lot of songwriters inhabit characters in their songs and sing in the first person but aren’t necessarily delivering their diary to their audience. People like Randy Newman, or even Bruce Springsteen.

Being online opens up chances to see new work and meet new people like Cory and Brendan, but it also means sometimes people will fake your divorce. How do you balance how much of yourself to share, and how much of your life to give to places like Twitter?

That’s the challenge. I don’t think I’ve found the correct balance. I think that it’s a disease, the amount of time spent looking at Twitter and reacting to it. I’ve taken breaks in the past and will try to do that more. But especially when an album is coming out, or a TV show is coming out, you want to promote it. But it also kind of fascinates me.

The other night, Donald Trump had started fighting with Bette Midler. All of a sudden, a tweet I had sent in 2012 to Donald Trump about another Bette Midler incident popped up again in the MAGA Twitter world. [They were] giving me shit for this tweet in 2012 that I don’t even remember, saying how unfunny I am. The whole thing is strange but also interesting to me in a way. People are out there, and I can communicate with them almost like in a chat room, instantly. They’re just out there. They’re people sitting at their computers just like I am. So I don’t necessarily want to shut that off because sometimes you can actually get in there with them and find out they’re not that persona they’re putting out online. They’re not that awful.