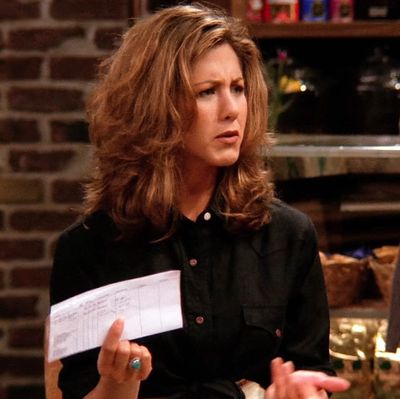

For years, the story of Netflix has been almost exclusively one about growth: more spending, more subscribers, more international production, more talent deals, more everything. But as this week’s news that Friends will be leaving the service for WarnerMedia’s upcoming HBO Max platform underscores, the years-long narrative surrounding the streaming giant has started to shift. While it’s still getting bigger on numerous fronts, Netflix is now dealing with the reality that much of the popular library content that helped power its early growth — The Office, Disney’s film slate, CW dramas — is going away. It is a significant and challenging moment for Netflix, for sure, but it is also one with an underappreciated upside. The company may be losing some of its best Friends, but it is also going to save billions of dollars, money it can reinvest in making even more original series and movies.

Consider: WarnerMedia and NBCUniversal’s streaming services reportedly paid $425 million and $500 million, respectively, to wrest away streaming rights to Friends and The Office for five years. Netflix will surely miss the billions of minutes that subscribers spent watching those titles, but some of the pain will be eased by having roughly $200 million more per year — almost $1 billion over five years — available for new content investment. Similarly, Netflix’s 2012 deal with Disney for access to the Mouse House’s latest feature films (everything from Marvel to Star Wars) was valued at about $300 million per year. Had Disney opted to negotiate an extension of that agreement rather than take back its library for its own Disney+ streaming service, it’s a safe bet Netflix would’ve been on the hook for much more — easily $1 billion-plus over several years. And then there’s the 2011 deal Netflix struck with the CW: The streamer is estimated to have paid well over $1 billion over the course of the agreement for rights to every new drama CW put on the air, including buzzy shows such as Riverdale and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. While Netflix isn’t losing those hits, the old deal expired last month and wasn’t renewed, in part because CW co-owner WarnerMedia wanted to put upcoming CW shows (such as the Riverdale spin-off Katy Keene) on its new HBO Max platform. While it’s impossible to know how much a new pact might have cost, Netflix will likely save hundreds of millions over the next five years by not having access to CW’s creative output.

Admittedly, this is the glass-half-full interpretation of what’s happening to Netflix, but it’s not to suggest this is somehow a “win.” To the contrary, losing tentpoles such as The Office and Friends is clearly not the future Netflix execs would’ve chosen for themselves. Ratings giant Nielsen recently said U.S. Netflix subscribers collectively spent 52.1 billion and 32.6 billion minutes, respectively, streaming The Office and Friends last year, easily making them the most consumed shows on the service. While Netflix often dismisses such data as incomplete or misleading, the shows clearly have a massive audience on the service: There’s a reason it paid a reported $80 million to keep Friends on the service for one more year, and offered to pay NBCUniversal hundreds of millions to retain The Office. And while I don’t put much stock in the random declarations of Twitter users swearing they’ll quit Netflix when the shows disappear, it would be foolish to think that how much certain subscribers value their Netflix subscription won’t change over time as Netflix’s all-you-can-stream programming buffet starts getting lighter in certain areas.

Remember: Netflix the past few years has been rushing to become not just another premium network, but the entire cable universe, offering the same variety consumers used to get by flipping from HBO to HGTV or from AMC to A&E. The Office and Friends most effectively filled the niche of TV Land, Nick at Nite, and TBS. Those disappearing Disney movies surely helped make Netflix more valuable to families and Marvel diehards, standing in for basic cable networks such as FX and TNT, which play such fare on an endless loop. Even if few people are paying $13 a month just to watch Friends on Netflix, it’s not a stretch to think some portion of the company’s subscriber base will be less likely to stick around if Netflix is no longer seen as one-stop streaming for a wide variety of content — including familiar favorites from traditional broadcast and cable networks.

But this is where all the money Netflix is about to save — as well as all the cash it’s been spending the last few years — becomes so important. Even though Netflix tried to hold on to shows such as The Office and Friends, it has spent years preparing for the day that the same companies who gladly leased their best content to Netflix would figure out they were helping build a competitive monster. The hundreds of new shows the streamer has debuted since House of Cards launched in 2013 were all part of Netflix’s plan to build up its own rich library of content, a fallback for when so-called legacy media companies like WarnerMedia and Disney finally wised up and realized they needed to build their own versions of Netflix. Genre fare such as The Umbrella Academy and Altered Carbon were green-lit in part because Netflix wasn’t counting on an unlimited supply of new Marvel shows. The flood of young-adult titles on the service, from 13 Reasons Why and The Society to On My Block, came in part because Netflix knew one day Disney and WarnerMedia would cut off the pipeline of shows from Freeform and the CW. The massive overall deals it made with former Disney employee Shonda Rhimes and ex-Fox staffer Ryan Murphy were partially insurance policies against something like the Disney-Fox merger and Disney’s takeover of Hulu.

Also, even if the studios had decided to keep leasing their best stuff to Netflix, in many cases it would have still made more sense for Netflix to invest in programming where it controls the rights and can’t be held hostage by an outside studio demanding more and more money. Former Amazon Studios exec and MediaREDEF columnist Matthew Ball notes that because “no one company can produce all of the best content or control all of the supply,” a streamer such as Netflix will always want part of its portfolio to come from outside suppliers. “But there are several major financial advantages to shifting internally,” he explains. “One, the markup on content produced by third parties is substantial. Two, you only pay for this content once, just like buying a house saves over rent in the long run. Third, you have more control over cancellations and spend. In many deals” — think the CW agreement — “Netflix can be forced to keep buying subsequent seasons of a show even if it isn’t working for them.”

Netflix actually went through a sort of dress rehearsal for what’s happening now about five years ago. In 2011, Netflix and Discovery Communications struck a huge deal to funnel a ton of programming from networks such as TLC, Discovery Network, and HGTV to Netflix. It proved to be wildly popular, so when the deal was up, Discovery demanded a lot more money, not unlike what NBCUniversal just did with The Office. The two sides couldn’t agree on a new pact — perhaps because Discovery didn’t actually want one — and the shows soon started going away. In 2016, Netflix chief content officer Ted Sarandos told an investment conference that Netflix didn’t suffer at all from the loss of the Discovery shows. “We replaced it with other programming that got us just as many viewers for less money,” he said. Indeed, Netflix eventually responded to the end of the Discovery pact by launching its own unscripted unit and greenlighting dozens of reality shows and documentaries, replacing the likes of Cake Boss and Mythbusters with Nailed It! and Queer Eye.

Of course, it’s exponentially harder to replace shows such as Friends and The Office. Unless Netflix designs a time machine, no amount of money can suddenly conjure up 200 episodes of a “new” beloved sitcom (though The Ranch and Fuller House were attempts to get there as soon as possible, and Grace and Frankie is very much an old-school comedy). But with all the extra cash about to be freed up, Netflix could decide to do a deal with an independent studio such as Sony (which owns Seinfeld and all the Norman Lear shows) or Lionsgate (The Hunger Games), though it’s more likely that another company, or possibly even Netflix, will instead buy those studios outright. It could also use the cash to increase its huge original content budget even more, maybe targeting fans of The Office with a new comedy from Steve Carell and Office showrunner Greg Daniels. Or Netflix execs might simply decide that all the work they’ve done the past decade to make their service indispensable to roughly 150 million subscribers worldwide — 60 million in the U.S. alone — means it is well-positioned to survive the loss of some very popular programming without increasing its content budget even more than planned. As Ball writes in a recent report, Netflix’s back catalogue has decreased by 66 percent the past six years, other streamers have joined the fray, and the cost of the service has gone up by 50 percent. Despite all that, its subscriber growth rate has remained steady. “Logically, today’s subscribers also shouldn’t need more content to stay with Netflix,” Ball says. “The current offering is, by definition, enough.”