Nostalgia is a funny thing. Sometimes, when we glance backward through our rose-colored glasses, images can blur. There is, for example, a fair amount of longing these days for the bygone charms of the video store, that special brick-and-mortar space we used to wander in pre-Internet days, despairing for VHSs out of stock before plunking down a few bucks for what was left. It was the possibility of discovery, be it instigated by one’s own interests or at the prompting of a knowledgeable clerk, that gave the retail space its particular magic. Bring up the video store to any film lover of a certain age, and they’ll likely tell you a story of how they found the Movie That Changed Their Life at such an establishment, often entirely by accident.

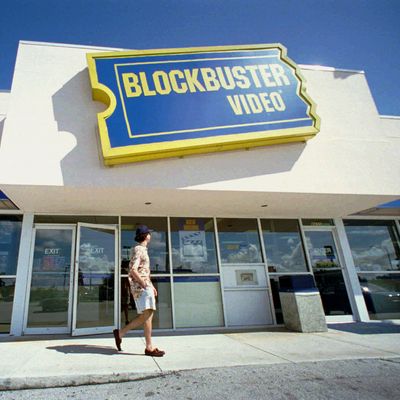

But too often, our nostalgia for video stores is translated into nostalgia for the Blockbuster Video chain. And we should accept no substitutions for the truth in this matter: Blockbuster Video was absolute garbage.

I can attest to this as a part-time employee of BV in the late ’90s and early 2000s. (It’s what you did when you were a broke cinema-crazy twenty-something with a headful of useless movie knowledge and a bottomless desire for free rentals.) The fact is, Blockbuster was never in the business of selling movies. What Blockbuster was selling was Product. And in terms of acquisition and presentation, it didn’t matter what that product was! The job of the store was not to curate art, or even to be particularly well-versed in it; its job was to move the inventory stocked. And what they stocked was right there in the name: Anything that wasn’t new was through. Stores included a few shelves of catalogue titles, sure, but they were frustratingly shallow, a meager, AFI 100-style collection of Hollywood’s “greatest hits.”

I’ve heard Blockbuster called “the Walmart of video stores,” which illustrates not only their sales strategy, but their history as an industry Goliath. Like the chain of retail megastores, Blockbuster achieved domination by muscling into new markets and putting locally owned mom-and-pop shops out of business with its deep pockets and seemingly limitless resources. (Its most effective tools were its agreements with distribution partners like Rentrak, which allowed Blockbuster to lease copies of hot new releases and pay the provider per transaction. Smaller stores, meanwhile, had to purchase those tapes outright, often at upwards of $100 per copy.)

Once Blockbuster’s market dominance had been established, the chain never missed an opportunity to flex its muscles. The company’s strict “R-rated and under only” policy not only meant that its stores lacked the “adults only” rooms typical of so many early video stores (and eyeballed by so many young video store customers, hello). Their policy also forced filmmakers who dared craft movies for adults — released as unrated or with the MPAA’s dreaded NC-17 — to create entirely different, often incoherent “R-rated” cuts for the chain, lest they lose that lucrative home rental income altogether. And thus curious viewers were subjected to bowdlerized versions of films like Requiem for a Dream, Bad Lieutenant, and Crash (no, the good one) if they lived in one of the many, many cities where Blockbuster was their only video store. And sometimes they weren’t even given that option; when Martin Scorsese’s controversial Last Temptation of Christ arrived on VHS in 1989, the chain refused to stock it altogether.

And then there was the cost. Every once in a while I’ll see a nostalgist complain (rightfully) that specific, seemingly canonical titles are unavailable on the subscription streamers but you sure could’ve found them at Blockbuster. What such malcontents often fail to note is those titles are frequently available for a la carte rental via services like Amazon and iTunes — just like at Blockbuster, and for less than the chain charged, even without figuring in inflation and late fees. And yes, let’s not memory-hole the late fees, egregious enough to not only prompt a class-action lawsuit, but the creation of a company that ultimately put Blockbuster out of business. The story of Netflix founder Reed Hastings launching the company’s original DVD-by-mail service in response to an outsized late fee has since been debunked, but it unquestionably struck a chord with the disgruntled Blockbuster customers that comprised their initial target audience.

For me, the best summary of Blockbuster Video came from the mouth of my store manager on my very first day of training. In a moment of downtime, I tried to make chitchat with the most reliable of video-store icebreakers: I asked for her favorite movie. “Oh, I don’t really watch movies,” she replied. “I mean, when you work around them all day, you don’t really wanna watch them when you go home.” I would love to tell you that this cockeyed perspective made her tenure at a video store — in which affection, or at least tolerance of motion pictures, would seem a necessity — a brief one. And shortly thereafter, she did leave the store, because corporate promoted her to district manager. Hers was exactly the kind of thinking that put a person on the fast-track to success at a company that reduced art to the aggrandizement of mediocrity. No amount of pining for the days of non-algorithmic recommendation and discovery should mitigate the plain truth that Blockbuster Video was monopolizing, price-gouging, lowest common denominator-catering gutter trash.

Anyway, RIP, actual video stores — and godspeed to the few that remain.