Before I saw What the Constitution Means to Me, I thought it might be an elaborate Broadway-themed episode of Punk’d, custom-made for me. When I sat down in the Hayes Theater, the set, a perfect rendering of an American Legion Hall complete with flags and framed photos of servicemen in funny hats, sent me into such a state of déjà vu I felt almost dizzy. Oh my god, I shout-whispered to the friend sitting next to me who did not appear to be experiencing the same attack of anxiety and nostalgia prompted entirely by the sight of fake-wood paneling. It really was JUST like this.

To describe the show simply: What the Constitution Means to Me sees playwright and star Heidi Schreck re-creating her teenage years spent giving speeches about the Constitution in the American Legion Oratorical Competition, a teen scholarship contest. The contest has been a thing since 1938. I entered it twice in high school, almost ten years ago, about two decades after Schreck did. You give a prepared speech — no shorter than eight minutes, but no longer than ten — about the Constitution broadly, as well as a shorter, extemporaneous speech about an amendment randomly selected from a preset list. (After that selection, you get five minutes to prep. My strategy involved writing entire five-minute speeches in advance and memorizing all of them.) My first time, as a junior, I competed a few times at the local level and bowed out after realizing that in the next round we’d be competing during a D.C. trip to Barack Obama’s first inauguration.

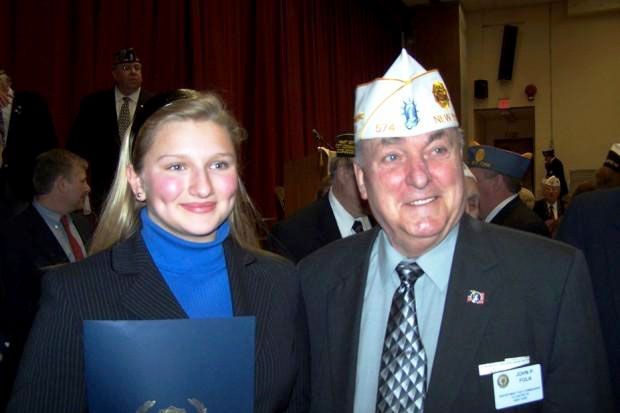

In my senior year I entered again, using the same speech as the year before. (It wasn’t against the rules. I checked.) That year, I made it all the way to the national level, collecting thousands of dollars in savings bonds and checks along the way. In Indiana, where the national competition is held each year, there was one speaker from every state. I made it out of the first round but busted in the semifinals, where they winnowed the field from nine of us to three. Spending weekends writing, rehearsing, and giving speeches about the Constitution in front of rooms full of old white men was not sexy, as Schreck also pointed out in a way that made me snort. None of my other friends participated. I did not exactly face stiff competition in the early regional heats. Per my hometown newspaper, “Malone Kircher won the local competition because no one else entered from her school.”

Schreck described the Constitution as “a crucible” of “sizzling and steamy conflict.” The contest, I learned by watching videos of previous competitors while prepping my own speech, is big on metaphors. Even bigger on anecdotes. Combine a few of those and some firm gesticulations, and you’re in business. For me, that involved a story about some elementary-school playground bullies who wouldn’t let me use the slide. This incident may or may not have actually happened, but I told the story with a conviction that would have made you think it shaped my entire teenage self and I’d thought of nothing but since it occurred. Telling off my bullies — “can too, it’s a free country” — was my way in to talking about the First Amendment and free speech. Midway through I’d pause dramatically and ask the audience to listen. “Do you hear that? Really listen.” Silence as shoehorned metaphor for oppressive, nondemocratic regimes. (And a convenient way to stall for time if I, having trained on Gilmore Girls and The West Wing, was talking too fast.) The judges lapped it up.

Looking at an old copy of my speech — saved by my loving magpie of a mother who dredged it up after I called her and talked a blue streak walking home from the theater — I see kernels of the woman I was just in the process of becoming and the life I would live. I talked about the Zenger trial and freedom of the press. I talked about Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the early women’s-rights movement. I talked about Hollingsworth v. Virginia, which established that the president has no role in amending the Constitution. (That one, of course, has less to do with me than with the current political climate.) But I also cringe at my narrow-mindedness, the oversimplifications through which I saw the world. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in hindsight, was a big, fat racist. There’s so much more I’d want to say today.

That’s what struck me most about watching Schreck. She gets to revisit all those oversimplifications. “I was like, ‘I can’t actually talk about the due-process laws with the Ninth Amendment without talking about my own abortion,’” Schreck told Vulture earlier this year. She delves into the generational trauma — her great-great-grandmother who was tricked by a man into moving to Washington as a mail-order bride, the physical and mental abuse her grandmother faced at the hands of her second husband — that deeply affected the women in her family, and into the broader traumas that are increasingly and alarmingly afflicting women in this country. She gets to do her no-fewer-than-eight, no-more-than-ten again. And she does them with a righteous and personal fervor that I’ll be genuinely sad to see leave Broadway after this weekend. (The show is being filmed for future release but details have yet to be announced.)

If I did it now, I’d probably opt out of wasting precious time quoting JFK’s “ask not what your country can do for you” speech in my conclusion. I’d delve into the women’s movement, warts and all, without restricting myself to talking about a white woman who wanted to help only other white women; the accusations of anti-Semitism that tore apart the Women’s March; silence as a metaphor for people who, in protest of the two-party system, didn’t bother to vote at all in 2016. I’d talk about the Fourteenth Amendment which now — at least for now — gives me the right to marry my girlfriend. I’d talk about Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. I’d talk about the disconnect between the rights spelled out in our so-called living, breathing document and the realities of how those rights are applied when you don’t look like the Framers or my onetime girl Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

That speech, even with gestures and dramatic pauses for effect, would not win. I remember, even at 17, arriving at nationals and having a distinct feeling that I did not love God or country enough for the crowd. (Schreck nods at this idea during the show and I found myself muttering a silent, I feel you.) That there was an inherent rigidity to things like gender and sexuality — at least in the judges’ eyes — that ought not be challenged. I made only a few friends there, one of them a guy who (last I checked in) had posted a picture of himself on Facebook wearing a THE FUTURE IS FEMALE shirt while standing in front of the Washington Monument. His caption was something about sticking it to phallocentrism. The winner that year, whom I remember as extremely kind, talked a lot about the family Bible. Schreck says her only real competition was a young woman who told delightful stories about her “pioneer grandmother.” Shreck pauses, then says, “I didn’t want to talk about my grandmother,” before revealing something about her not at all delightful life. The messy, real stuff, I imagine, probably still gets left offstage for anybody genuinely looking to win. Now there’s a metaphor.