Ken Burns is influential enough to have inspired his own bit of cinema grammar, the Ken Burns Effect, which describes a certain way of panning and zooming over a still photo. But there’s another kind of Ken Burns Effect, a cycle of emotional and intellectual reactions, that viewers may experience yet again as they watch his latest, the 16-hour, eight-part Country Music.

This Ken Burns Effect begins with awe at the staggering too-muchness of a Burns project. In Country Music, it’s not just the running time or the breadth of research materials that impresses (100,000 photos, 700 hours of clips, 101 interviews). It’s the typically Burnsian chutzpah of giving a monumental project a plain-vanilla title as simultaneously unassuming and grandiose as Jazz, Baseball, or The Civil War. It’s the endless parade of country, pop, rock, and folk superstars (including Wynton Marsalis and Jack White) and the soundtrack’s treasure-trove jukebox of hits — everything from “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” and “Keep on the Sunny Side” to “Crazy” and “I Fall to Pieces.”

And it’s the intelligence of Burns’s filmmaking, which is sometimes mistaken for mere craftsmanship. Notice, for instance, how he regularly starts his signature zoom-outs with close-ups of microphones, speakers, Victrola funnels, and transmitters befitting a tale of art spread by new technology. Or how he illustrates the idea of a musical legacy by collapsing past and present: Often, a surviving country star is asked to comment on a song written decades or even centuries before their birth, and they begin to sing the lyrics, and Burns layers their performance over a scratchy recording.

Even more haunting is how both white and African-American musicians will talk about the multicultural nature of country — a blend of African, European, and Latin American traditions — and then Burns will cut to a photo of a group of revelers playing and dancing together, stay on the image long enough to let us notice that everyone in the frame is white save for one or two African-Americans, then zoom in to isolate them, underlining the point that, while the artistic cross-pollination was mostly affectionate and democratic, the money still landed mainly in white folks’ hands.

Unfortunately, it’s in these sociopolitical aspects that Country Music loses focus and, seemingly, nerve. Which brings us to phase two of the Ken Burns Effect: the moment when the viewer realizes that an episode — and by extension, the series as a whole — doesn’t have as firm a handle on the big-picture stuff as it wants you to think.

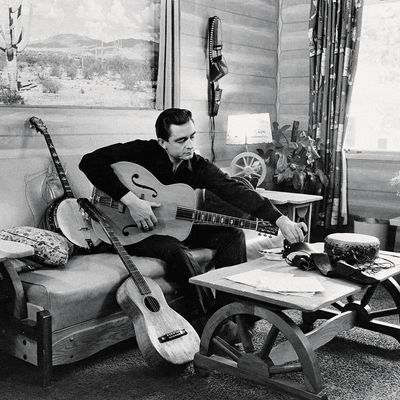

Like so many other Burns projects — in particular The Civil War, Jazz, Baseball, and The Vietnam War — Country Music diligently brings up the social iniquities baked into the American experiment and shows how they manifested themselves through unequal access to money, opportunity, and power, but the series doesn’t always follow through. You get a bitter little taste of racism here and there — mostly at the start of the films-within-a-film, where Burns zeroes in on a performer and stays with them for a few minutes. But then the series becomes intoxicated by the legend of whoever’s life is being recounted (understandably so, when the subject is as complex and charismatic as Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, or Loretta Lynn) and turns into a glorious info-dump of newsreel images, photos, music, and mementos (including the envelope containing the fan letter that Cash wrote to a young Bob Dylan).

Burns gets dinged by conservatives for turning his blockbuster projects into considerations of American racism — as if national life wasn’t not so secretly about that anyway — but this time, he keeps doing a catch-and-release thing, which is frustrating given how revelatory and damning the details are. A photo of white minstrels in blackface; a section dealing with Cash’s thwarted attempts to get “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” on the radio and being harassed by white supremacists for having a “colored” wife (who was actually Italian); an account of Jimmie Rodgers, the Anglo son of a railroad foreman, being taught blues music by poor black railroad workers, then inventing his “Singing Brakeman” persona and becoming country’s first superstar: Such mesmerizing sequences suggest a bolder, more challenging, but far less pledge-drive-friendly series.

Country Music’s treatment of sexism is even more intermittent: It should have made more of how so many lesser-known female domestic partners and colleagues did artistic or emotional heavy lifting for famous men without getting proper compensation or credit. (One of them was Elsie McWilliams, who wrote 39 songs for Rodgers but got credit for only 20 and helped him learn them by ear because he couldn’t read music.) Female country superstars like Parton and Lynn do their share of heavy lifting for Burns as well; ditto Charley Pride, one of country’s few African-American stars, who emerges as one of the series’ most eloquent and wrenching commentators.

Burns isn’t cynically avoiding the subject of inequality, mind you. It’s all over Country Music, just not as consistently as in his masterworks. Whenever he loses that thread, it’s often because he’s so excited about whatever performer he’s profiling that he can’t help turning into one of those brilliant teachers whose recitation of all the cool stuff they discovered during research becomes a show in itself at the expense of a more pointed historical critique, or in this case, a sense of how the promise and problems of country music resonate in the present. Like Jazz, which jammed the past three decades of the genre into a few minutes, Country Music avoids commenting on anything that happened after 1996. Burns says this is because he’s in the “history business,” an explanation that lets him sidestep political minefields like the Dixie Chicks’ anti–Iraq War protests and the incendiary statements of Charlie Daniels and Hank Williams Jr.

And it’s here that we enter phase three of the Ken Burns Effect: You look over the totality of what he has done in this production and others; at his generally solid track record at being all things to all people, even ones who gripe about what he could’ve done better; and at his knack for getting millions of people to hang on every minute of, say, a 12-hour series about national parks, and you are forced to conclude that he is, indeed, some kind of master, and that this is, all things considered, one hell of a show.

Even the stoniest resolve tends to crumble whenever Burns’s sensibility intersects with screenwriter Dayton Duncan’s tumbling Faulknerian sentences and narrator Peter Coyote’s matter-of-fact delivery of them (which dries them out and makes them paradoxically even more affecting). The three of them together are as crackling an ensemble as the bands they profile. The account of Jimmie Rodgers’s death from tuberculosis at 35 should come with a warning for viewers to keep Kleenex within reach: “The Southern Railway added a special baggage car to its New Orleans run to carry the Singing Brakeman home,” Coyote intones, in his barroom Atticus Finch rasp, over Rodgers’s recording of “Miss the Mississippi and You.” “His pearl-gray casket covered with lilies rested on a platform in its center, with a photograph of Rodgers dressed in his railroad uniform: two thumbs up, the brakeman’s symbol that everything was ready to move on.” Then Burns cuts to that very photograph of Rodgers with his thumbs up, and you fall to pieces.

*A version of this article appears in the September 16, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!