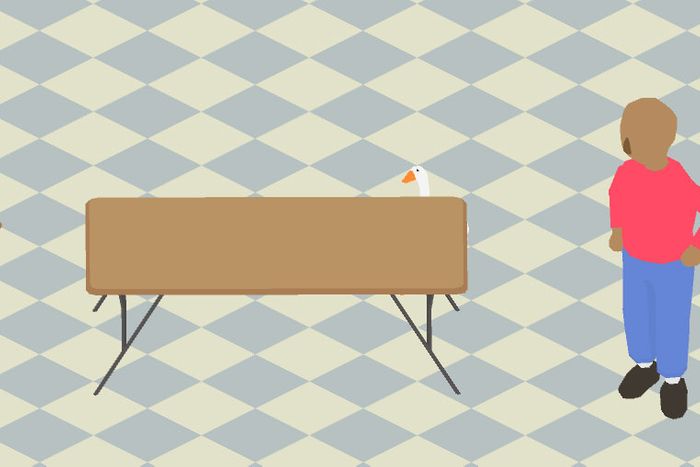

Suddenly and somewhat unexpectedly, the internet has become obsessed with a game about a goose. Untitled Goose Game is simple: You, a goose, wander around a small English village and enact mild, hilarious chaos. You irritate a gardener by stealing some of his belongings. You honk at startling moments. You make some of the villagers do awkward, annoying things to deal with your mischievous shenanigans. You break a few things, but nothing all that important. The worst thing that happens is someone’s thumb gets a little hurt.

Untitled Goose Game is improbably fun, at least in part because of how low-stakes it all is. It’s silly and gentle and smart. Propelling the goose through the pleasant, bucolic environments feels like engaging in some ultimately harmless misbehavior, a playground of sanctioned naughtiness where you’re definitely going to ruin someone’s day, but you’re never going to destroy anyone’s life.

After playing through all of Untitled Goose Game in almost one sitting (and forcing myself to stop before starting in on the post-game extra credit), I talked with Jacob Strasser and Michael McMaster, two of the four-person indie game company, House House, which created and developed Untitled Goose Game. I asked them about the uncanny appeal of the goose, how the game developed from its earliest concepts, and the idea of the goose as a leftist icon. (Spoiler: They love this idea.)

The game started when someone just put a picture of a goose into your Slack and said, “Let’s make this a game,” right?

Jacob Strasser: Yeah, that was our colleague, Stuart Gillespie-Cook. There was never really any intention that we should make a game about it, he just saw a stock photo and remembered that geese were funny, like, conceptually. We all agreed that geese were very funny.

What was the motivation for turning the funny goose into a game? There’s a big distance between “this image is funny” to wanting to make a full game out of it.

Strasser: When we were finishing our last game, Push Me Pull You, We had a lot of different ideas floating around for our next game. We knew we wanted to make a game in 3-D. We wanted to make a single-player thing. We were very interested in depictions of community and having this character that you could puppeteer so you could embody this physical thing.

Stuart made this joke about the goose and we had a laugh about it, and then we said, “Okay, let’s go back to more serious ideas.” But when that didn’t quite work, we finally said, “Oh, what about that goose thing?” Eventually we turned around and realized that it could be a serious idea, a viable game.

It’s interesting you were thinking about depictions of community. The goose seems like it’s mainly a disruption of the community, this asshole goose who keeps showing up to disorder everyone’s lives.

Michael McMaster: The original pitch for this goose version of the game was that there’d be this large-scale simulated English fête — a country fair is kind of the American equivalent. We had this image of a huge crowd of people, and you as a goose would come in and disrupt that. But we didn’t really think through how complicated it’d be to design and program this completely systemic fête. What happened then was this slow process of winnowing down the concept so that rather than this massive crowd of people, it became this collection of a handful of people.

I’d imagine that was mostly a practical issue? With a huge group of people you’d need so many possible interactions between all the people and all the objects in the world. Did you ever play with the idea of there being a fail state in the game?

Strasser: As we were building out the game, actually, the first ingredients we needed were the goose and the person. We very quickly realized that the low-level relationship between a goose and person was really interesting and really rich, and had all this opportunity for depth and nuance and humor. The big crowd scene was too macro to allow those sorts of things to happen, so we realized it was more interesting to have fewer people and allow those relationships to exist more richly.

The lack of a fail state is because of that relationship, and because of how grounded it was.

McMaster: The relationship feels quite real, and quite tangible. To turn that into a violent fail state would just feel so egregious in this setting. We wanted to keep it as realistic as possible.

Strasser: We never wanted there to be any threat of violence or open hostility between the players and the game. We were more comfortable with the idea that, yeah, maybe they’d shoo you away as maybe you would a goose in real life, but unless you’re a hunter or an animal-control person, you’re not going to do anything more than that. It was a way to keep it low-stakes in that personal, intimate way that we quite liked.

You describe the relationship between a person and a goose as one of depth and nuance. I definitely experienced that while playing the game, but would never have said that I’ve experienced that with a goose in real life. Did it take a long time to get from “Here’s a funny picture of a goose” to “This is a relationship with depth and nuance”?

Strasser: It happened fairly early. One of the earliest prototypes of the game was a very rough version of the garden that’s in the game now, just a big open green space with a man who looked very similar to our current groundskeeper, and the goose. We made a few props, and the man cared about the props, and the goose could pick them up. The basic early blocks were there.

It was quite instant. We used this thing called inverse kinematics, which is a way to make game characters look at stuff, basically, and we set it so the goose would look at where the gardener was. No matter where he was in the world, the goose would turn his head to look at him. And the gardener would do the same. And just having those two characters look at each other — the world was totally bare, it was pretty rough and early — but having two characters look at each other in silence had all this stuff in it. Just that eye contact creates this relationship that you can put so much meaning into. It happened early on. And it was very, very funny. I remember just feeling like we’d landed on something special.

I love the ending very much. I laughed so hard at the final shot, but I don’t want to spoil it for anyone who hasn’t played it. Where did that idea come from?

Strasser: We did have this big blank space for how the game was going to end. We threw around a lot of ideas. It didn’t have to be that exciting from a gameplay perspective, but we wanted it to feel like it came to some sort of closure.

McMaster: Probably the core of the idea of the whole finale sequence was that we wanted it to feel like the entire town was now unified against you, and you had to go back through the space that you’ve just wrecked havoc in and account for it in some way. [Laughs.]

Do you have personal favorite details in the game? Small things you’re particularly fond of?

Strasser: I really love the drinking fountain in the garden. I made it really really late in the game, and modeled it and thought, “Ah, that’s the perfect drinking fountain.” [McMaster laughs in the background.] No one else will look at it, but it’s in the credits. [Some background muttering.]

I’ve just been tapped on the shoulder by our colleague Stuart to say that in the backyards level, there’s a little statue of a fish that’s got legs. Just for the record, his and probably my favorite thing in the game is this little statue of a fish that internally we refer to as Jeremy Fish.

Where did Jeremy Fish come from?

Strasser: Stuart, do you want to come tag into an interview for a bit?

Stuart Gillespie-Cook: I guess there’s a Beatrix Potter character called Jeremy Fisher, who’s like a funny frog who dances ballet, maybe? We wanted the character of this woman who has all this stuff in her backyard to be a bit wacky. So we spent a while trying to come up with different lawn ornaments she could have, and Jeremy Fish was the best of them.

McMaster: The other thing I wanted to mention: There’s this sequence where you rush through a house and get kicked out of a door, and it feels like maybe the biggest indulgence we took with the game. It doesn’t have a lot of gameplay opportunity, and you can only interact with it one way. It’s a single gag in an entire game. It took so much work to make you move through the house in that way and get kicked out the door, and if you’re carrying an item it gets thrown out after you in this really graceful way. I’m very glad that we spent probably way too much time to get this one very specific gag into the game.

There’s been some very small but angry political responses to the game. Have you seen any of it? Do you have any feelings about it? It’s hard to figure out the political angle on this goose without doing a super Marxist reading.

Strasser: We have a joke canonical version of the world of the game, in which — I don’t think you should publish this, but for the sake of conversation — it’s set in a world where a goose chased Margaret Thatcher out of office, leading Tony Benn to take over the U.K. and enact social democracy in the U.K. All the people are good Marxists, and they’re all good people, and the goose is just a goose. All the people on Twitter responded to that saying “Oh, I feel bad that the goose is harassing these Marxists.”

[Laughs.]

Strasser: I’m not going to go on Twitter and correct people because I have better things to do, but the goose is just a goose. The goose is this chaotic neutral character. They’re just an animal who’s not really aware of what they’re doing.

So I don’t need to read into the game to try to figure out which of the people voted for Brexit?

Strasser: You can if you like! You’re very welcome to predict whatever you’d like. We’ve got our joke canon.

McMaster: I’m glad that the goose is a leftist icon; that’s very funny. I’d much rather it be a leftist icon than a right icon.

Have you heard of Gritty?

McMaster: Oh, if he can be the new Gritty that’d be fantastic! Anything the left can take joy in and pride in and have a bit of fun with, we love. And if it pisses off some alt-right people, then great.

Strasser: That will maybe happen no matter what.

Do you have any thoughts about why the game has resonated with people as much as it has?

Strasser: I think your guess is as good as ours? We made a game that we thought was funny, about a goose.

McMaster: The way I’ve always thought about it is, it turns out people have strong feelings about geese. Maybe without realizing how strongly they felt about it. So it creates a moment of joy. There probably is something more interesting there, but I’m not sure what it is.

Strasser: Yeah, I don’t think we’ve figured it out.