“Do you have any advice for writing about people who do not look like you?”

I was at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference this summer, on a panel of writers of color. We talked about our concerns, from supporting the work of other marginalized writers inside of predominantly white institutions to finding ways to create community. Jericho Brown, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Lauren Francis-Sharma, and I took questions from Cathy Linh Che. It was a good conversation. Near the end of the discussion, we opened it up to the audience, and then we found ourselves at this question.

I realized I had been waiting for it. Dreading it a little. The question has been a mainstay of literary events ever since Lionel Shriver took to the Brisbane Writers Festival stage wearing a sombrero and delivered a defense of writing whatever she wanted, about whomever she wanted. Online, it has become one of those fights with no seeming end.

Before Shriver, this was a topic for difficult and meaningful pedagogical conversations, often led by writers of color in YA and sci-fi and fantasy, like speculative-fiction author Nisi Shawl, whose book Writing the Other, co-written with Cynthia Ward, is considered a go-to guide. As the writer Brandon Taylor wrote on Lit Hub, there is no shortcut to putting in this work, and yet the problems that arise from authors’ not giving it the necessary thought mean there is now what he calls “a cottage industry of minor fixes,” from sensitivity readers to freelance editors, who work with this focus.

Given all the excellent writing about the challenges of rendering otherness, someone who asks this question in 2019 probably has not done the reading. But the question is a Trojan horse, posing as reasonable artistic discourse when, in fact, many writers are not really asking for advice — they are asking if it is okay to find a way to continue as they have. They don’t want an answer; they want permission. Which is why all that excellent writing advice has failed to stop the question thus far.

I don’t answer with writing advice anymore. Instead, I answer with three questions.

1. Why do you want to write from this character’s point of view?

We write what we believe a story is, and so our sense of story is formed by the stories we’ve read. But for most of us, the stories we hear are the first stories that teach us. Stories from family. Stories in the news. Stories we’re taught at school. Gossip, trash talk, and jokes, which are the shortest, complete form of narrative. How you grew up, who you grew up with, how you know them. All of this affects what you think is real, and whom you think counts as human — which, in turn, affects how you write stories.

The traditional role of the storyteller is to tell the stories of a community, or stories that have inscribed the values of that community, or both. Modern fiction works differently. It’s less overtly connected to any idea of a debt to a community, but there’s always a relationship back to that role. I do believe that much of the shape of an idea for a piece of fiction depends on what you think the word community means, and how you experience it at an unconscious level.

I once advised a young white writer who believed that because she had loved a novel written by a writer from a certain background that she, too, could write about a family from that background. Her country had colonized this country, but a condition of being a colonizer is that you do not know the country you are taking possession of, or the culture — you don’t have to. I knew the questions this student still had to answer because I knew people from this community. I had to draw her attention to everything she didn’t know. She seemed resentful throughout. Her previous adviser had believed she could write this novel, too.

But if you’re not in community with people like those you want to write about, chances are you are on your way to intruding.

2. Do you read writers from this community currently?

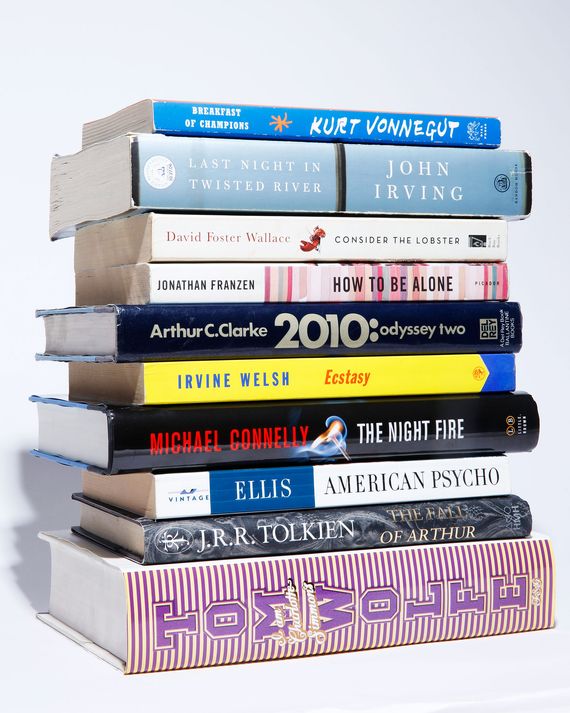

People don’t often know their blind spots until they do a simple audit of their bookshelf. When I go to literary parties at editors’ homes, I experience the shelves upon shelves of white writers like a rebuke. Most of what has survived to us thus far is literature written by white male writers. The last three decades especially have seen a struggle to revive the books we’ve lost — books by women, people of color, and queer writers — and to then try and write out of that recuperation a new tradition. But most of us writing now were not educated by that expanded canon.

I teach roughly seven writing workshops a year, and have since 1996. For the 24 years I’ve been teaching creative writing, the stories I see have predominantly been about white people, or characters that mysteriously don’t have any declared ethnicity or race at all. This is true no matter the number of students of color in the class, and no matter the amount of writing I assign by writers of color, and even, to my surprise, no matter the declared radical politics of the students. In general, the beginner fiction that writers produce is what they think a story looks like. Those stories are often not really stories — they are ways of performing their relationship to power. They are stories that let them feel connected to the dominant culture. There was one day last year when two queer Korean-American students both submitted stories about queer Korean-American characters, and it felt like the dawn of a new era.

This brings me to the flip side of this question, a question for the rest of us who aren’t white men: How do we write our own literature? I am thinking of when I interviewed Ursula K. Le Guin and she told me she had to teach herself to write as a woman. Or my own first stories, when I did much the same as these students. In the 1980s, I had to learn how to write myself and people like me onto the page. My own life on the page felt impossible to explain in any detail when I was a student writer. I had to ask myself why I was embarrassed to mention that I was Asian-American, much less to center it in a story. Strangely, it took finding writers like Mavis Gallant and Gregor Von Rezzori, whose works described characters who had lived among several cultures, as they were writing about Europeans. Reading about someone who was of Austrian and French heritage may not feel like a mix of cultures, but I unexpectedly found permission there — white writers teaching me how to write mixed-race Asian-American characters like me.

3. Why do you want to tell this story?

I think every writer needs to ask themselves this question. But the urgency of it takes on a different shape when we think about other cultures.

A few years ago, I was on a train, headed out to Portland, Oregon, and I met a retired British couple, a man and a woman, at dinner. They were both white. She looked like Camilla Bowles and he looked like James Bond’s dad, complete with a black eye patch over his left eye and striking, swept-back silver hair. The woman was more social, intent on drawing me out. When she learned I was a writer, she asked me what kind of writer, and I told her. She apologized for only being interested in mystery novels. I know that it was just her being polite — people who only read mystery novels believe they are a superior form of writing. Her husband seemed uninterested in our conversation, until he learned I taught writing, and then he seemed to light up.

“Do you believe writing can be taught?” he asked. I said I did, unlike some writing teachers. He told me about his desire to write mystery novels. He was a retired police detective. His wife rolled her eyes as he talked about how crimes aren’t solved in real life the way they are in mystery novels, and eventually, she brought the conversation to a halt, saying, “I just don’t want him to be embarrassed.”

Later, as I wrote in my journal, I had the idea to write a novel about a police detective who has just retired, who wants to write mystery novels, and his wife, who only reads mystery novels and doesn’t want him to. He has spent a career solving crimes he can’t talk about. He begins writing about two unsolved cases, and while the writing isn’t going well, he is drawn eventually into trying to solve them. I even wrote 100 pages of it and sent it to my readers, who then began a process like the one I use with students, asking me questions.

Everyone liked it. But there were questions. Does this have to be set in London? Is there some way it can be set in the United States? One reader told me foreign editors typically dislike Americans writing about Europe and the U.K. because of how little the average American writer knows about these places. And while one of my most enthusiastic readers had been raised and educated in the U.K. and provided me with a library of books to help with finishing it, I questioned myself.

I wasn’t stealing the story of the retired detective I’d met — the novel I would write would never resemble his—but I was trying to use my idea of him and his wife as the main characters. I was interested in the crisis a retirement can be within a long marriage. I was also interested in writing a thriller. But I realized that it required a level of work I wasn’t sure I was willing to do — hire the equivalent of a British sensitivity reader, for example, since I would be almost colonizing the colonizer, as it were.

In trying to figure out if I should write the above story or not, I asked myself these first three questions, and then three more, which I got from conversations with the writers Kiese Laymon and Chinelo Okparanta:

Does this story contain a damaging stereotype of a marginalized group? Does the story need this stereotype to exist? If so, does the story need to exist?

A stoic white retired British police detective and his wife did not at first glance seem like damaging stereotypes. But even in thinking about this, I had to ask myself why I wanted to write the novel. Other questions grew from that. Did I really want my next novel to be set in London? Wasn’t there enough to write about in America? What was I doing writing about a white man? Even if I wanted to write a meta–murder mystery, wasn’t there some other way to do it? The long-standing Anglophilia I had developed when the first queer books, films, and music I found came out of the U.K. in the 1980s was something I had come to watch out for.

I eventually figured out how to set it here in America, though it has taken a back seat, joining the five other ideas for novels and another book of essays all lurking in my files.

These discussions distract me increasingly from the conversations I’m interested in. If I’m helping students cross boundaries, I urge them to look at the ones they find within. I also urge them to set them for themselves. I’m more interested in how there’s another literature possible when people who belong to the status quo challenge it from within. I’m thinking of Jess Row’s novel Your Face in Mine, a story that explores taking on an identity you weren’t born into, literally, when the narrator discovers a white Jewish friend from high school has had surgery to “turn” himself black. Row, who is white and Jewish, pursues the peculiar turns that are possible when someone with white privilege seeks to rid himself of his guilt — not through restorative justice but through camouflage and counterfeit. Or the inimitable Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous, an autobiographical novel set in the second person. The narrator writes the novel to his mother, who is unable to speak or read English and will never read it. This direct address to her — Asian-American refugee to Asian-American refugee — is drawn out of that history and intimate proximity. It uses the Japanese literary form kishōtenketsu, a dramatic structure that refuses to deploy conflict. No rising arc, no “climax.” Vuong was influenced by canonical works like Moby-Dick, but he uses them to feed his daring, to write something entirely new.

I was with him recently at NYU for a night of readings. He said two things that night that I still think of. “What is pretentious but to have the pretense to the assumption that you belong here?” And, “If you are an Asian-American writer, artist, poet, or painter, prepare to be unfathomable, inconceivable.”

These are two polestars, a North and South. One was what I perhaps still needed to lay down, and the other was something to pick up. In my reluctance for my retired detective narrator, I could finally see how tired I was of the idea of having to pretend to be a white man, or be like one. Better to catch the energy that rises when I fling myself at everything I fear writing.

Increasingly, this question is a trick question. A part of a game where writers of color, LGBTQ writers, women writers, are told to write as white men in order to succeed, and thus are set up to fail. While white men are allowed to write what they think the stories of these people are, and are told it is their right. This game is over.

So when I meet with those beginner students to discuss their first stories, I ask them to think of stories only they can write. Stories they know but have never read anywhere. Stories they always tell but never write down. That’s what this question is really about. Or could be. If the questioner asked it of themselves more often than they asked other people.

Alexander Chee is the author of How to Write an Autobiographical Novel and an associate professor of creative writing at Dartmouth.

*A version of this article appears in the October 28, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!