This interview originally ran in November 2019 but we are republishing it in celebration of the debut of Don Hertzfeldt’s World of Tomorrow Episode Three.

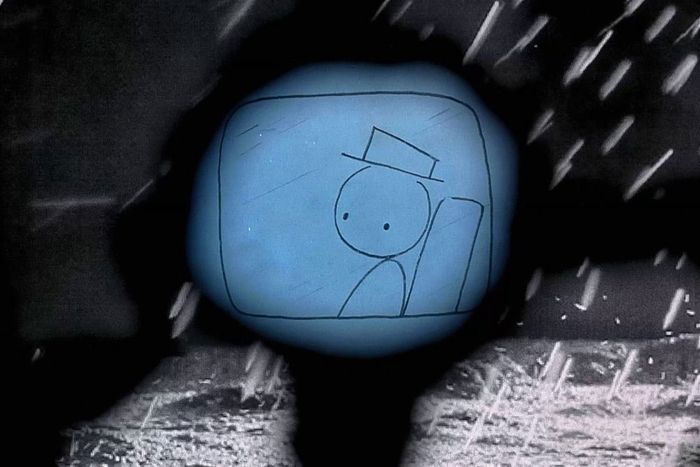

So it should be no surprise that Hertzfeldt’s latest work is a bracing, wearying, utterly hilarious portrait of dreary modern life — and that it comes bearing the title The End of the World. It’s a new version of a graphic novel Hertzfeldt put out in 2013, comprised of Post-It note drawings and other random sequences that never quite made it into his short films. Revised and expanded, The End of the World boasts the same stick-figure-simple drawings we’ve come to love from Hertzfeldt, as well as the dark worldview that shouldn’t be as hysterical as it turns out to be. (One page’s drawing is captioned: “Thank god they only eat children.” Another: “With a dying breath, he posts some bad poetry.”) Flip through this gorgeous collection and you’ll see the funny, sad, profound aesthetic that informed It’s Such a Beautiful Day, the 2012 feature that revolves around a man’s unknown neurological illness, and 2015’s World of Tomorrow, which tells of the misadventures of a little girl (adorably voiced by Hertzfeldt’s niece Winona Mae) and her clone from a bleak future. (The 2017 follow-up, World of Tomorrow Episode Two, was equally crushing and sublime.)

Hertzfeldt’s work — primitive and wry as it is — has always felt like a treasured secret, a gem you discover and then pass along to someone special. That under-the-radar quality has made his infrequent inroads into the mainstream — two Best Animated Short Oscar nominations, his guest-spot animating The Simpsons’ opening couch gag — surreal interludes in which a brilliant outsider flirts with accessibility. He’s always exuded a scruffy, alt-rock energy, and it comes across in The End of the World, as well on its copyright page, where he writes, “One day, many years from now, this book will be discovered beneath a fading, forgotten pile of dusty, long-lost ephemera belonging to someone who is no longer around and a person will pick it up and think, what on earth is this? and then they will read this and they will think, ha.”

To celebrate his new-old book, and his influence on 21st-century animation, we interviewed Hertzfeldt in a series of emails, as is his preference. Along the way, we discussed surviving as an independent artist on the margins, the projects he’s turned down in favor of working alone, and whether we’re all doomed — a very Don Hertzfeldt-ian subject.

Were you interested in revisiting The End of the World in part because you felt like you didn’t get the story “right” the first time? Have you been wanting to change/tweak the story all this time?

No, the new book isn’t that different from the first edition. It’s just a few pages longer. A lot of stuff got cut from the first edition. I was throwing things around right up until it was published, and for this one I added back a couple old things that maybe shouldn’t have been left out. I was always going to update everything on the “copyright” page because that’s still one of my favorite parts of the book. For people who haven’t read it yet, I guess that sounds like I just threw the whole book under the bus.

The book is despairing at times, sometimes hilariously so, if despair can ever be hilarious. But it comes from such a dark place. Was this a particularly difficult period in your life when you made it?

No, probably the opposite. If I’m feeling depressed the last thing I’m ever going to want to do is get any work done. I think in general, it usually takes a lot of optimism for me to do anything creative.

The human characters in your work are always drawn simply — straight lines for arms and legs, dots for eyes, etc. Did you know early on that you preferred simple depictions?

When I was a kid learning how to draw, I had a much greater interest in newspaper cartoons than in animation. In those years, the comics section of my parents’ daily newspaper published a sort of holy trinity for me with “The Far Side,” “Calvin & Hobbes,” and “Bloom County.” These were all characters with dots for eyes and simple limbs because a comic strip was engineered to be read very quickly, as someone skimmed through the newspaper. An iconic strip like “Peanuts,” at its peak, was just perfectly composed. There was never a wasted pen stroke, never any fat. Everything in the frame had a place and purpose.

Newspaper comics were never considered “high art,” but this effortless minimalism is very difficult to master. I find a big correlation between those old comic strips and directing an animated scene. While a newspaper reader only gives a comic strip a few seconds of his time to deliver its message, I’m dealing in shots that often only last a few seconds on the screen. Why isn’t this shot working like it should? Oh, it’s because I’ve distracted your eye momentarily with the junk I put in the corner of the frame and you weren’t looking where I wanted you to look. Over and over again in post-production, if something isn’t working like it should, it’s because I did too much: the composition was too cluttered, the design was too confusing. One of my favorite words is clarity. I’m always reducing. And that’s what a cartoonist does naturally. You strip everything down to only show what you need to show.

Often, film journalists and reviewers refer to animation as a genre. How do you feel about that?

I guess I’m not really surprised. “Genre” in film is only supposed to refer to narrative … and animation is a medium that can do anything, right? But after a hundred years of American animation studios only ever bothering to make family comedies, I can see how a mainstream audience could make that mistake. From their point of view, most popular American animation can pretty easily all be lumped into the same narrative category. Maybe someone could even argue that all the modern Disney/Pixar/Dreamworks movies really do belong to the same genre, within animation. I just don’t know what you would call it.

Looking at your career, it almost seems closer to the model of an indie band — just doing your thing, living within your means, doing it for the art as opposed to seeking some major-label deal. In terms of how you think about your work from a business/financial perspective, are there other artists you model yourself after?

It’s such an unusual thing to do this independently that there weren’t many other people out there with a path I could try to follow. Other countries have film boards and government support for the arts, but in the States, I don’t know a single animator who’s ever been given a large grant. To make a movie here, you’re either going to pay for it or find work with a studio. In the late ’90s, I was actually signed up to write and direct an animated feature for 20th Century Fox.

And I had countless other meetings with just about every animation producer in L.A. At the time, every studio wanted to take on Disney animation but they were all afraid of doing anything that Disney wouldn’t do. So everyone was pretty weirded out by every idea I pitched and nothing ever went anywhere. I was later offered a live-action teen sex comedy to direct and decided to then just carry on with my own stuff.

So I don’t think I’m as allergic to the major-label deal as much as they’ve seemed allergic to me. But being forced to be independent all these years and having to produce everything alone, I own everything now and am probably making way more money than if the studio route had worked out. But I’m still looking for a studio willing to bankroll the much bigger ideas that I could never possibly animate alone.

I don’t know if I’m so much of an indie band as I’m a solo dude who’d just like to get some more musicians in the room.

When did it feel like animation could become a viable career for you?

I was lucky to get started really young. I made four 16-mm. cartoons while in film school and they all found nationwide distribution, which is super strange. I was really aggressive about getting them out into the world because they were a ton of work to make and for me what, otherwise, was the point? The Spike and Mike animation festival toured them everywhere — they were on MTV, even at the Cannes Film Festival, all while I was still going to classes on little sleep. When you’re 19 and you suddenly don’t have to get a job because your student film is actually paying the bills … oh my God! That frees you up to make the next cartoon, and the next. I kept thinking, how long can I get away with this? The faculty just gave me the keys to the building where the animation camera was housed so I could go shoot on campus anytime in the middle of the night.

How easy was it to learn the business/financial side of your job? Some artists just don’t have the skill set to deal with budgeting, making a living, etc. Did you discover you had a knack for the non-art part of your profession?

I haven’t really thought about that but I guess I did take to it sort of naturally. There’s a chunk of my brain that likes to strategize and can somehow very easily shut down the other half and slide into the industry aspect of all of this. It’s also helped over the years that I’ve never had any big, dumb, expensive habits to waste whatever money I did have on. But I also had little choice but to learn. I probably wouldn’t be talking to you today if I hadn’t been able to figure out the money stuff. If each one of the early cartoons hadn’t been profitable somehow I wouldn’t have been able to make the next one and that probably would have been the end of the whole animation experiment before I was even out of college.

You’re just not going to survive very long in America being an idealistic fluffy artist if you’re not also watching your back. I think one of the most valuable things I learned very early on was simply how to say “no.” That probably sounds a little obvious but it’s not in everyone’s nature, especially when you’re young and there’s some sort of vague opportunity in front of you. Your human instinct is to always want to be agreeable and to be liked, and to say “yes” to whatever’s being offered. When you’re young, you feel grateful and lucky that anyone is even paying attention to you at all. But what a powerful thing to be able to say “no.” It’s one of the first steps toward realizing your worth.

With arts education being cut and artists finding it increasingly difficult to support themselves solely through their work, how much harder would it be starting out now than when you were first getting going?

When I was a student in the ’90s, it was obviously much harder to make anything (digital was not around), and much, much harder to actually get your work seen — I probably mailed thousands of VHS tapes to film festivals everywhere, and I really had to learn how to hustle. I was a teenager trying to figure out how to read a theatrical contract and sort out my international distribution rights. I had to be tenacious about not just making the movie, but then starting all over again and spending as much energy on getting it seen and getting paid. And I had to be burned by several bad deals to finally figure out how to actually get what I wanted out of a contract. What all that did was make me learn how to be a producer. I had to become extremely protective of the work and adamant about actually making money.

Most young filmmakers today aren’t being put through that anymore because the short-film model has totally flipped. Getting your work seen now is, weirdly, the easiest part. You can immediately upload your stuff and loads of people will freely see it, but no one is going to pay you for something that you just gave away. So if I were starting out now, I’d probably be very confused. There are more options out there than ever before to create and show your work, but most of them are totally unsustainable. The next time you have a plumber over to the house, offer to pay them in “exposure” and see how it goes. Why are artists and musicians the only people treated this way? The one thing that will never change for an artist wanting to make a living at it is you have to get paid. And there is still no individual path to follow, or especially specific advice that I could give. Everyone is constantly still trying to figure all this out with each new release and new platform.

But while the internet kills off all the old distributors that I used to rely on, the internet has also allowed the audience themselves to fill that gap by bringing them in touch with me directly. That has been a seismic shift. I’m not mourning the current lack of old school distributors because as long as I own everything, I’m more than happy to take over their job. Instead of buying my work through a third party where I used to earn much less, today the audience can just come get it directly from the source. And that’s an amazing thing, knowing that the audience has been funding all my stuff by themselves for so many years now.

Do you like social media?

Social media actually inspired the title, The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts for the second World of Tomorrow. That’s what I feel on social media.

You mentioned in a recent Facebook Q&A that you work really slowly. Has that always been a challenge for you? Have you tried to find ways to work faster? Or is it simply part of your process that you know the animation takes a while?

The one thing that will always be true of all animation anywhere is that it will take a ridiculously long time. And if you’re animating it all by yourself, forget about it. It’s like those Tibetan monks creating beautiful sand art with their little tools. There are just no easy shortcuts. You have to disappear into it, and if you actually do find an easy shortcut, it’s probably going to make your sand art suck. A few years ago when I made the shift to animating on a digital tablet instead of paper, I was able to speed things up just a bit — I made the first World of Tomorrow and a short thing for The Simpsons at the same time and that seemed like a miracle of speed. But in the grand scheme of things, it’s still like a snail crawling 10 miles on a wet sheet of glass instead of 10 miles on dry concrete. Wooo, we’re really flying now!

It’s always fun to complain about, but I’m a person who loves being alone so I’m not sure I’d call it a challenge. It’s just what we do. When you’re a snail, you can’t really express surprise at how long things are going to take. The real game-changer would be having the budget and support in place for a larger crew. That would help me release things dramatically faster, possibly even at a speed some might consider “professional.” Then it would be like having a large team of snails … all pulling the one snail in a little chariot or something. I don’t know how to make that metaphor work anymore.

Where does your sense of humor come from? Did you have a sardonic family growing up?

I don’t think so, but maybe somebody else who knew me back then would say yes. If you grow up in a house full of monkeys, maybe you’re going to think it’s totally normal for everyone to have grown up in a house of monkeys. But I don’t think of anyone in my family as being especially comedic. My brother and I were always drawing our own comic books and trying to make each other laugh, but as he was older than me, it was almost impossible to earn a laugh out of him. My dad has a good sense of humor and Monty Python airing on PBS was a pretty big deal in the house. I also remember being pretty funny in school, but then puberty hit and I never wanted to speak to anyone again.

Considering your book is about the end of the world, this might seem like a strange question, but … well, do you think we’re all going to be OK? Are we going to make it through all of this?

Oh, I think you and I are going to be just fine. Not so sure about our kids.

More From This Series

- Every Studio Ghibli Film, Ranked

- The Hardest Thing I Ever Animated

- Women Are Taking Over Fox’s Sunday Night Cartoons. What Took So Long?