I wear comfortable but unfashionable clothes, eat the same cereal for breakfast every morning, and since 2007 I have been the editor of the humor site McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. I check our submissions in-box while vacuuming, walking my dog, and checking out at the grocery store. I read submissions in offices and waiting rooms, in subways and airplanes. I contemplate them while making a sandwich, getting my teeth cleaned, and picking my son up from band practice. I think about humor writing throughout the day, every day.

McSweeney’s receives anywhere from 200 to 300 submissions a week, and I try to read and respond to each and every one of them within five to seven days. A small percentage of my replies are acceptances, but the overwhelming majority are not. I’ll be the first to admit that sending rejections is a lot easier than receiving rejections, but just the same, “killing dreams” (as my wife refers to it) is not something I look forward to. Even less fun is when I receive the occasional vitriolic reply from an angry writer.

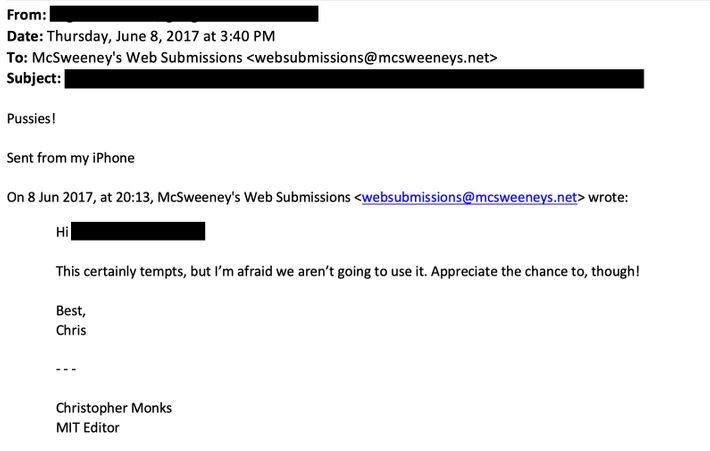

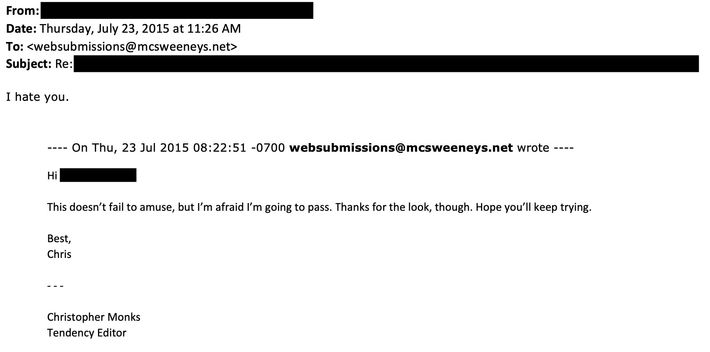

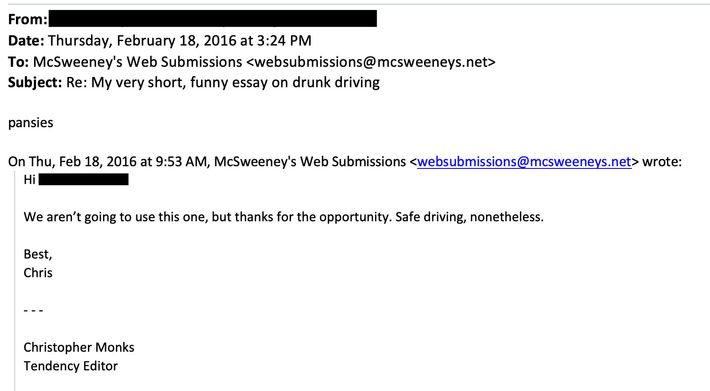

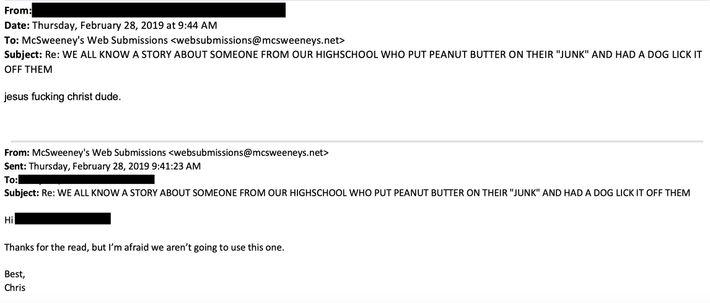

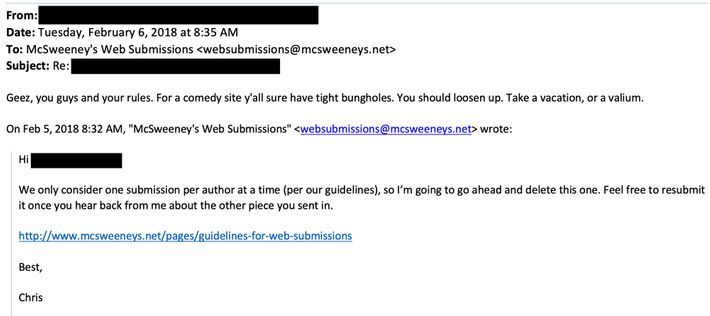

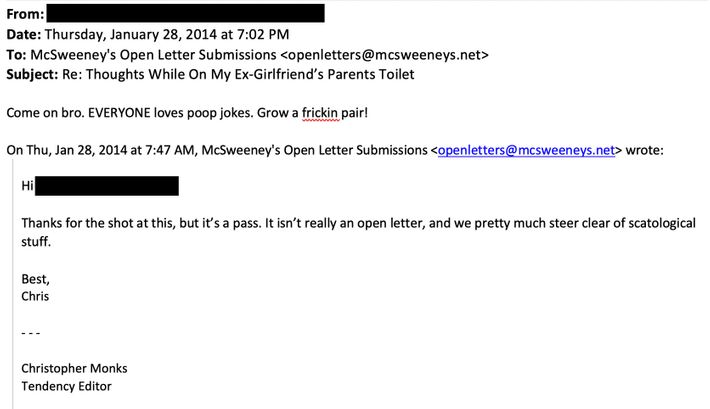

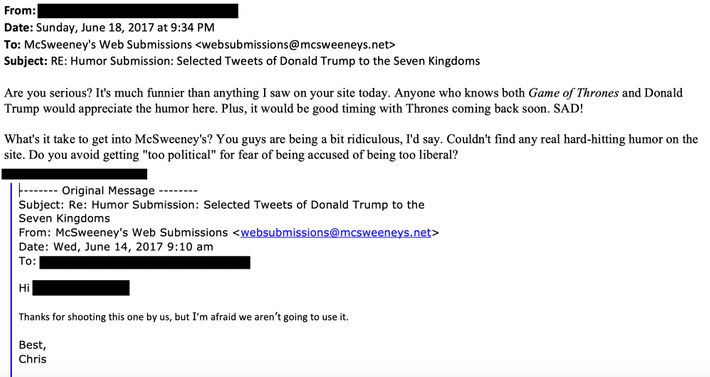

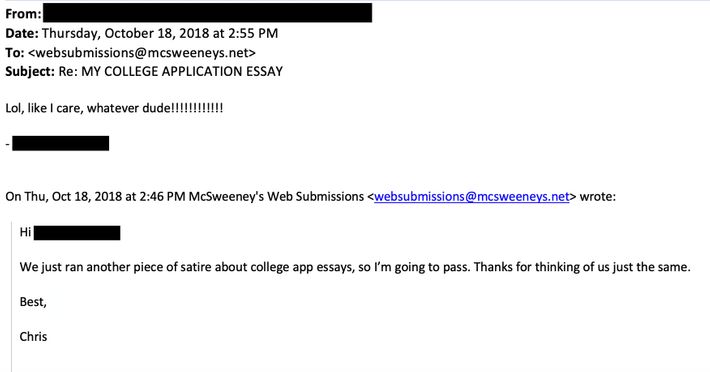

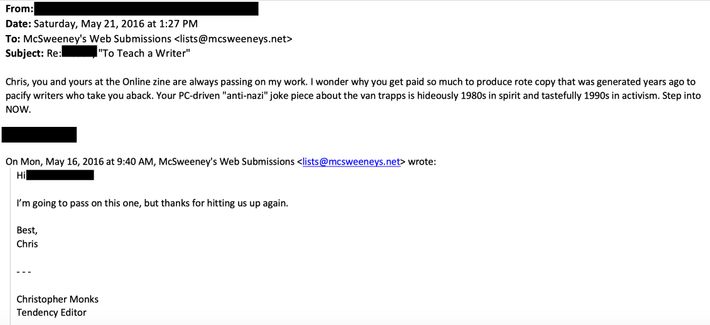

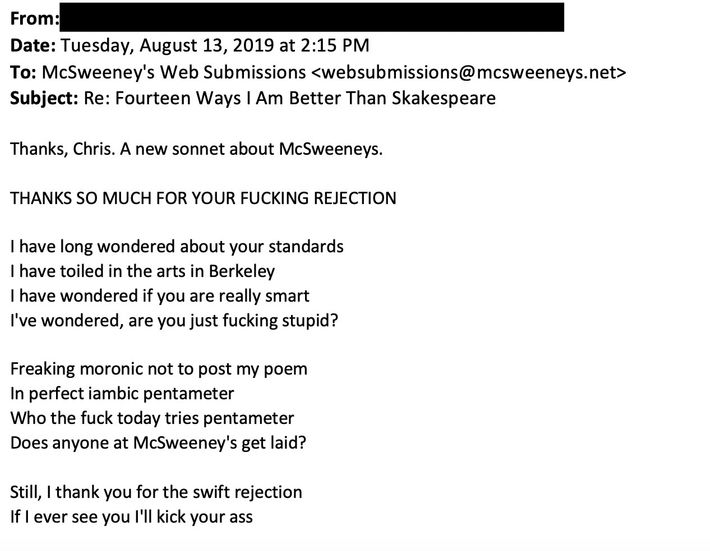

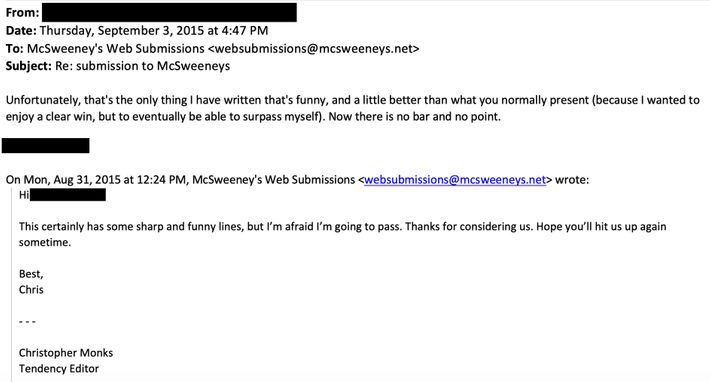

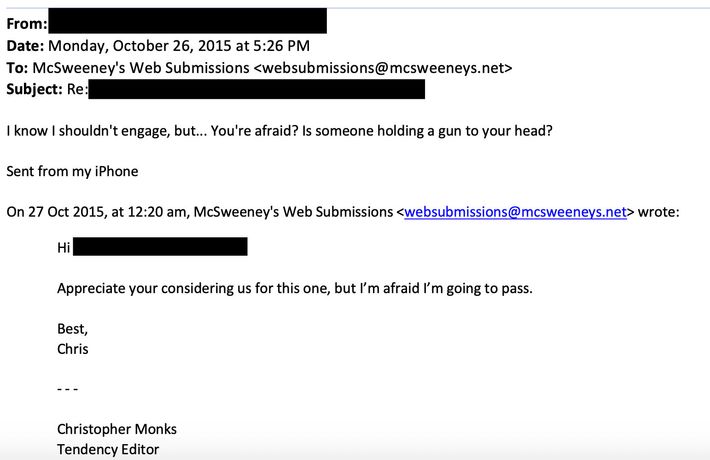

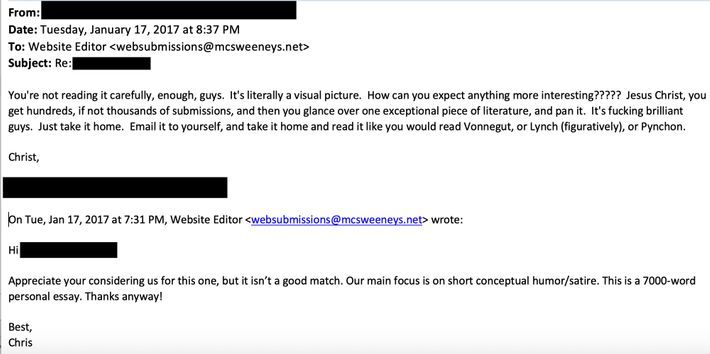

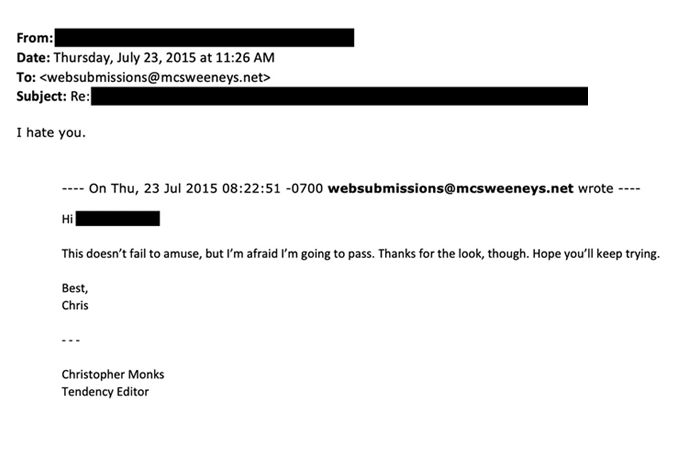

I empathize with the frustration of not getting your work published, but it still sucks to receive these sorts of emails because, you know, I have feelings. By nature, I flee from any signs of interpersonal conflict, so I rarely engage and fire back an equally snarky response. Instead, I place these mean messages in a folder I’ve titled “Jerks” and occasionally share screenshots of them (with the names of the jerks redacted) to my followers on Twitter.

I know all about rejection. Sure, I dole it out frequently, but I’ve been on the other end a lot, too. I, too, am a veteran struggling humor writer. I know what it’s like to work forever on a piece, meticulously crafting a joke, until it feels just right and worthy of submitting. I am familiar with the adrenaline rush of clicking “send,” and the overwhelming wave of dread and second-guessing that follows. And I am no stranger to the interminable waiting for an answer back, a yes or no, please not a no, but, yes, it will probably be a no. It always feels like it’s going to be a no.

I’m not trying to paint myself as some sort of hero, just something more than an email signature that judges writers’ latest creative outputs. I care about and look forward to reading submissions, and while that may not always be evident in my one- or two-sentence rejections, I understand the ups and downs of the submissions process. Having been on both sides of it for years, I’ve learned that there are a few relatively simple things writers can do to give their work a better chance of acceptance.

Read the Submission Guidelines

Editors are sticklers about their site’s submissions guidelines. Some guidelines are short and direct, others are long and ironic and require a good five minutes of your time, but just the same, power through and read them. Because if you submit your work in an incorrect format, or fail to include your contact info, or write a 500-word cover letter when the guidelines say that cover letters aren’t necessary, an editor will notice. In many ways, the guidelines are just as much for the editor as they are for the writer, because they help organize submitted pieces and make them more manageable to read and evaluate. More importantly, if it’s obvious a writer hasn’t read them carefully, it makes it easier for an editor to say no.

Read the Site You’re Submitting To

Again, I can relate to desperately wanting to get your work out to the world, but if you haven’t read a site thoroughly and gotten a handle on the type of humor it publishes, your chances for acceptance will be very, very low. There are different kinds of humor sites that cater to different kinds of humor. So, if a site says it’s looking for political satire, don’t send in a poem about that crazy night you had in college. If their focus is on literary parodies, don’t send a personal essay about your sordid history with dishwashers. If they put out a call for funny open letters, don’t send them a monologue of a person sitting on their ex-girlfriend’s parents’ toilet, pooping.

Checking out a site before submitting will also help you decide if you actually want your work to appear there. Don’t simply take the word of a friend or a co-worker or a writer’s-market guide; study a site to see if you find it funny and if your writing will be a good match. Otherwise, you will just waste your time sending work to a place that you really don’t find all that great.

In addition, many humor sites run topical pieces, so reading a site before submitting will help you avoid sending a piece about something that they have already covered.

Be Conservative With Your Cover Letter

Cover letters are tricky, because while they can help personalize the writer-editor relationship, they may lead to a few pitfalls. Editors have to read a lot of submissions, so it’s best to keep things short and sweet. A quick “Hello, here is my piece. Thanks for reading” is more than sufficient. Save the humor for your submission, because if a joke bombs in your cover letter, it could taint the assessment of your work. Mentioning past credits is fine, but unless they include well-known publications, an editor will likely skip over them. And avoid any inkling of presumption; saying “I think this piece is a perfect fit your site” will just rub your editor’s fragile ego the wrong way. Yes, they are unfashionably dressed and eat the same cereal every day, but they are their site’s gatekeepers, and they know well and good what is and isn’t a fit for their site. Just let them have this faux sense of power, please. It’s one of the few things they have in this world.

Oh, and always make sure to know which humor site you are submitting to.

Don’t Bombard an Editor With Submissions

This one is a little delicate because I appreciate diligence, and being able to write consistently is admirable. There are some very talented writers who churn out funny piece after funny piece. With that said, if you are sending multiple ultimately unsuccessful submissions over a short period of time to the same publication, you risk looking like you’re trying to throw whatever you have in your drafts folder in hopes that something will stick. Taking a week or two or three between submitting to the same site will at the very least give the appearance that you are honing your comedy and only sending what you feel is your best, most well-crafted writing — which is what you should be doing anyway.

Don’t Be a Jerk

The big one. It should go without saying, but angrily replying to a rejection will get you nowhere. Humor is subjective, laugh riots are on a spectrum, and sometimes your piece just isn’t a good match. If you need to vent, curse the editor out in your head instead. Or trash them to your spouse or mail delivery person. Or print out a photo of them and use it to line your pet cockatiel’s cage. Whatever you do, just don’t write back something snarky and spiteful, even if you’ve come up with a spectacular burn, a clever guilt trip, or scathing advice on how they could do their job better.

Thankfully, the vast majority of writers put in the time and research and submit appropriate and properly formatted work. When they receive a rejection, they do their best to shrug it off and not take it personally. Most humor writers are friendly, receptive, and perseverant. If they respond to a rejection, it is typically with a “Thanks for considering!” or “I’ll keep trying!” For the record, this is not sucking up. Okay, maybe it’s a little sucking up, but sucking up is better than just being sucky. Writers are typically fans of the site they are submitting to and have set a goal to get published on its pages, so they return with a pleasantry or two and soldier on. Odds are they will submit something else shortly thereafter.

Over my years working at McSweeney’s, there have been many, many writers who have been rejected many, many times over who kept keeping on and eventually landed pieces on our pages. I myself was rejected over a dozen times before getting published on the site. Rejection comes with the territory. Accepting it and moving on to the next piece is the way to go.

Being a jerk works against your own interest, because in all likelihood, an editor will no longer consider your work for their site. There are tons of other writers who are able to come to terms with a “no” and carry on with their writing lives. An editor will continue to focus their attention on those folks and leave you and your jerky wallowing by the wayside (i.e., the spam box). So, the safest choice is to put down the can of gas and box of matches and let the bridge stand by not replying to a rejection altogether.

But, if you absolutely must, write up a draft and let it sit for a few hours before sending. Odds are, you’ll eventually cool down, come to your senses, and delete it. (I have actually done this a handful of times after receiving particularly jerky rejection replies. It feels good to write them, even better the next day when I’m glad I didn’t send them.) Trust this editor and fellow struggling humor writer: It isn’t worth it. Otherwise, it’s #WelcomeToTheJerkFolder for you.

The email screenshots included are actual replies to rejections sent by Chris Monks. Writers’ names and other information have been redacted out of respect for their privacy and jerk-dom.

To celebrate its 21st birthday, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency has released a new collection of its funniest accepted pieces, Keep Scrolling Till You Feel Something.