R.E.M. broke boundaries, first as an upstart ’80s indie-rock band equally indebted to folk-rock acts like the Byrds and hook-smart post-punk stars like U2, and later as the model for considerate rock stardom and political and humanitarian activism that the figureheads of the ’90s alternative-rock boom would often look to for guidance. They were a wellspring of hits from day one. The first song on their first album — “Radio Free Europe” off 1983’s Murmur — set the pace for what turned out to be a 30-year presence on the Billboard singles and album charts. They retired in 2011, having scored several classics and very few duds. Their reluctance to follow trends made them unique and unpredictable. Their constant quest to challenge themselves made magic. Their desire to make the world outside of rock and roll a better place inspired as much as their recorded work did. R.E.M. is inarguably one of the greatest American rock bands of all time.

This month, R.E.M. continues a decade-long campaign of reissues with a six-disc 25th-anniversary deluxe edition of 1994’s Monster that houses a remaster of the original album, a remix by producer Scott Litt, unreleased demos, a full live show from the 1995 tour, and a Blu-ray disc with all of the band’s music videos from the era and the 1996 tour documentary Road Movie. It’s a big box and deservedly so, because Monster was a pivotal moment. After touring extensively throughout the ’80s, R.E.M. avoided the road entirely in the years when their cultural cachet skyrocketed thanks to the bucolic folk of 1991’s Out of Time and 1992’s Automatic for the People. Monster cut a hard left in the band’s method, embracing loud guitars and glam-rock posturing at drummer Bill Berry’s request that they record an album that would crush on their first tour in five years.

The sessions were taxing and profoundly affected by the deaths of River Phoenix and Kurt Cobain, the latter of whom had befriended R.E.M. singer Michael Stipe in the early ’90s. Monster sold well but ended up lining used bins in record stores as jilted listeners looking for a sequel to Automatic revolted. And the tour was plagued by illness: Berry suffered a brain aneurysm in the winter of 1995 that later led him to leave the band, and multi-instrumentalist and backing vocalist Mike Mills had surgery to remove a benign tumor that summer.

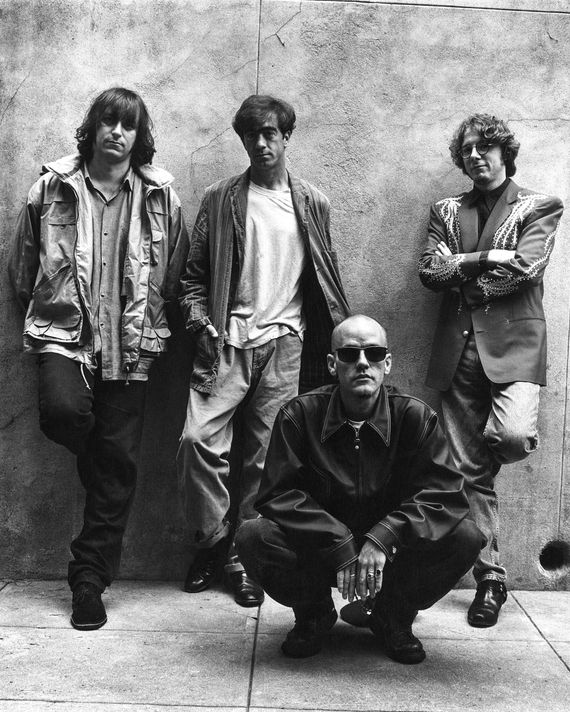

Despite the tumult, R.E.M. is proud of its achievements. I met with Stipe and Mills in late October to discuss Monster’s legacy and the state of modern mainstream rock and roll (such that it still exists) and got some gems about navigating queerness in ’90s rock and what Cobain was like when the cameras weren’t rolling, along with an update on Stipe’s long-awaited debut as a solo artist, initiated with his new single, “Your Capricious Soul.”

R.E.M. walked an interesting path in the ’90s. When grunge exploded, you were making beautiful, quiet music. People adjusted to that, then you gave them guitars and distortion. By the end of the ’90s, there was no sense of what ground R.E.M. couldn’t cover. What inspired you to evolve so quickly in that era?

Mills: Rule No. 1: Don’t do the same thing again. Peter [Buck] was always the engineer of the musical train we were on, and since he wrote the bulk of the music, we let him kind of determine the musical directions we were taking. Starting with Green but then on into Out of Time and Automatic, he wanted to move away from the electric guitar and try to write some songs on different instruments. By the time we’d taken five years off touring and getting ready to do Monster, he was ready to get back on the electric guitar and start making loud noise again.

Stipe: And he bought an amp that had tremolo. To this day, I don’t know if we discussed glam rock or if we just kind of all arrived there. We had disappeared after the Green world tour. I didn’t do press. We’d made these two records that were hugely, hugely popular. We never wanted to repeat ourselves, and we were going on tour. We had to do something loud and raw and with swagger; glam rock was the most obvious place for us to mine.

Consequently, at the same time, I spoke publicly about my sexuality in the lead-up to Monster. I shaved my head ’cause my hair was thinning. Mike grew his hair out into a Prince Valiant and started wearing Nudie suits. We were changing to do what artists do, which is to be part of the moment, and to hopefully push that forward in a progressive way.

Mills: We had to present ourselves to the world for the first time in five years. Nobody had really seen us. They just heard our record. We didn’t want to present the same R.E.M. they had seen in ’89, so we were like, How can we do something different? And we just did it pretty radically.

Stipe: Now we’re massively famous and these songs are really massively huge and we’re gonna have to play all of them, but they’re all really mid-tempo and slow so how do we respond to that? Monster was our response.

It seemed like, if you’d wanted to, you could’ve been the undisputed biggest band of the ’90s. You didn’t want to play the game?

Mills: We never wanted to be the biggest band in the world. We just wanted to be the best band we could be. The whole point of every record deal we ever signed was to give ourselves complete control over when we recorded, what we recorded, how we recorded it, where we recorded it, and with whom we recorded it. We were perfectly willing to sink or swim on our own efforts. If it didn’t work, then we owned that. If it worked, we owned that, too.

What was in the air in ’93 and ’94 that drew all these gritty records about masculinity and power dynamics out of everyone? You’ve got Monster, you’ve got Zooropa, Versus, In Utero.

Mills: I think part of it was getting out from under the darkness of the Reagan-Bush era, because there was just such a cloud that hung over everything. And then when Clinton came in, it felt like there was a bit of a weight off. You could focus on identification and self-awareness and the face you were presenting to the world, different topics other than the weight of a shitty government.

Am I wrong to say there’s an aspect of the performance of masculinity in Monster in the same way Bono had with Zooropa, in portraying a character?

Stipe: I totally took from him, yeah. Absolutely. Those were the first U2 records I really loved. I thought their being able to make fun of themselves and at the same time present music that’s really fun to sing along with and really fun to listen to was brilliant.

With these reissues, are you just making sure everything stays in print, or is there an aspect of the stewardship of a legacy? Or do you just want to clear up the vaults?

Mills: We are curators of our own legacy, and we do care about how it’s remembered and perceived. Since we broke up eight years ago, it’s okay to look back now. We can revisit this stuff and look at it with a bit of a different eye than we would have if we were still a band recording and performing. And obviously, if you’re gonna do it, you wanna do it right and try to present a legacy that we feel we created.

Stipe: In a way, that’s why we ended the band when we did, because we had nothing left to prove to ourselves or to anyone else. And we didn’t want to drag that legacy into the dirt. It just felt like the best way to honor it is to encapsulate it and walk away. All this stuff is sitting in the archive. We’d rather do it ourselves now then have someone do it much, much later. It’s not like we’re gonna chuck it in the trash, you know?

If you could go back to those sessions, would you do anything differently?

Stipe: There are a few songs I would’ve spent a little more time with. I mentioned “King of Comedy” the other day, and this guy said, “That’s my favorite R.E.M. song ever.” It was a fun, good idea. But, for me, it didn’t completely gel in the recording. Neither did “Ignoreland.” That’s a song really we overworked and overthought. And did not allow it to be … everything it could be.

The early critical reading of Monster fixated on the sex and relationship stuff, I think almost to a fault, when really the record was about getting out of character, outside of yourselves as players and writers. Was that the intention?

Mills: The record really is about ironic distance. It’s about separating who you are from who you present yourself to be, both in real life for the characters in the songs and for us on the stage. Going onstage in front of 20,000 people is both the most real and the most unreal thing you could do as a human being. When you go on the stage, you’re not the person you are ten seconds before you walk onstage. We decided to run with that. I wore those incredible suits, which I would not really walk down the street in, but they’re perfect for the stage. It was just a whole new persona for the band that they hadn’t seen before.

In the old profiles, Michael, there’s an eagerness to get you to own the queerness in the characters on the record in the moments when it came up. How did you handle people trying to label you and box you in?

Stipe: My situation makes a lot more sense in 2019, in terms of people understanding that there’s nuance and there’s fluidity and that we don’t have to think in these binary terms. That’s what I was trying to press back then. I did an okay job of it, but I got blowback from all sides. And that’s okay. It did what it needed to do for me and for anyone who didn’t quite understand. We were all a little bit flummoxed that anyone had any doubt that I was something other than straight at that point. It was pretty obvious from our first record that I was different in a bunch of ways. I think one of the things I’m most proud of is that I only ever presented myself as who I am. I never had a beard; I never pretended to have a girlfriend who was for the cameras or whatever. I was never that guy. I was always completely and uniquely myself, for better and worse. But yeah, people did try to box me in.

Artists have a longer leash now to be themselves without really subscribing to a specific vision of sexuality. Are you watching anyone now who’s embodying that?

Stipe: This is one of the things that the 21st century’s offered us: generations that understand. It feels like it’s a part of their DNA that there are not these categories, and if there are, we’re gonna blow ’em up. “Guess what? I have a new name for what I am that you’re gonna have to learn, and you’re gonna have to recite it back to me.” And sometimes it can get a little attitude-y, but that’s okay. It’s really beautiful to me, that idea of fluidity, not only within sexuality but also gender, gender identity, and desire. Desire is something that can shift from day to day.

You know who embodies that in a way I find very, very interesting is Billie Eilish. It’s less about her sexuality; I don’t know a thing about her sexuality. She’s a teenager. But the way she presents herself is not … you know, I was a bit disappointed as a fan when FKA Twigs started wearing lingerie. I was like, “You were the female singer who doesn’t have to do that.” And now she’s doing it. I like that Billie Eilish presents herself in these kind of baggy sweatshirts and the scary makeup. She’s not playing this kind of male-gaze idea of what a woman should be that I think a lot of people do, a lot of women.

I’m glad that I’ve always been a kind of vulnerable male figure and that it maybe helped some people to make sense of that — if they had a certain way of thinking about what that means — and that we’re now at a place where it’s a given that you can be whatever and whoever you wanna be and no one’s gonna really question it that much.

Well, change is like a rubber band: You tug in one direction and sometimes things snap back the other way. So right now, there’s an openness and an ability to teach different ideas. But there are people actively resisting them too.

Stipe: Of course. In a conversation I had with, of all people, Bill Clinton, the night before his wife handed [the 2008 Democratic presidential primary] over to Barack Obama, he was talking about how, in American politics, there will always be an expansion followed by a deep contraction. Change is hard, particularly in a country this big and as young as we are. We still have these locked-in ideas of our own mythology. When that breaks into camps, it can get quite dangerous.

We’re having an extreme contraction right now.

Stipe: I would agree with that.

Do you see an end to that? Or are we staring down the end of the world you predicted on Document?

Stipe: No, but I’m an optimist. I feel really strongly that we’re gonna have to get even dirtier than [we are now] in order to recognize what it’s gonna take for us to pull through, and I think we will pull through. If you talk to my more woo-woo friends, they’re gonna tell you that this is the beginning of the Age of Aquarius, and the age that we’re coming out of is the end of the alpha male. But he doesn’t go easy. So he’s gonna claw. He’s gonna cling. And he’s gonna be pulled away screaming and kicking. I do feel that we’re moving toward something that is more inclusive and progressive, but we’re having to go through pretty dark times to get there. We’re in a very, very weird transitional place right now, if you consider digital technology and the advances that are being made in science and medicine. So we have these leaders that are decimating whatever’s left of an intelligent thinking person’s idea of what we should be now and where are we headed. It makes perfect sense that this is when it’s happening.

Out of the shadow of the ’90s, Kurt Cobain feels like a figure who was thinking the way we think now. Talk to me about getting to know him, what people who never knew him personally might’ve missed.

Stipe: He had a great sense of humor. He was very self-deprecating. He was really funny. He was smart like I’m smart. He wasn’t book smart or academic, Ivy League smart. He had a different kind of smart, and it made sense. You had to listen sometimes to make sense. He was a good father. I think the things that are unexpected is that he wasn’t just this sad, depressed, mopey guy at all. He wasn’t that. He was a little bit shy. His eyes were the bluest eyes you ever gazed into; his eyes were ultramarine. They were so crazy. When I first met him, I looked him in the eye and was like, Holy shit. This is real. This is on. Like, the guy is part alien. He really came from somewhere else.

Michael, recently you released “Your Capricious Soul,” the first single officially billed under your own name, with proceeds going to the environmentalist organization Extinction Rebellion. Is there a plan for more music down the line, or is this about leveraging your name to get attention on that issue?

Stipe: I’m definitely leveraging my name to get attention on that issue, but that issue and that group are what compelled me. I had the track for a year and a half just sitting around, but I was scared to release it, honestly, because there’s so much expectation coming for any of us. Following R.E.M. is a very difficult act, so I’ve been working on composing and writing and recording my own stuff. Extinction Rebellion is what pushed me to go ahead and release [the song] and align it with the first worldwide protest that we did the second week of October. For the first year of its release, every penny of my profits goes to Extinction Rebellion. And I’ve got other songs that I’m considering releasing. I’m not working toward an album, because I don’t want that pressure right now. But I will have an album’s worth of material in no time if it keeps going like it’s going.

How do you feel about the state of rock and roll in this decade? People are moving a little bit away from the electric guitar and opting for more atmospherics in their records instead. How do you feel about that?

Stipe: Outside of an attitude, I don’t really know what rock and roll means in 2019, to tell you the truth. I’m not being arch. It’s not the kind of music I am drawn to listen to. In fact, I don’t listen to very much music at all. Music, for me, becomes a barricade to everything else. If it’s Western pop music, I’m picking it apart and trying to make it better, trying to edit it or rearrange it. It’s distracting if I’m in a conversation or trying to focus on something else, to hear Western pop music. I listen to ambient music a lot. I like Nils Frahm. I like Billie Eilish. I like some pop music but only in cars that are taking me places that’s less than 15 minutes. I really like Sia.

Mills: Oh, I hate her! I wish to God I had written “Chandelier.”

Stipe: Yeah, me too. What a great song.

Will the Up album ever get the reassessment it deserves?

Stipe: You think it should?

I think so. But I’m speaking as someone who was 17 when it hit, and I was really drawn to the sadness in it. But I think it was unfairly looked over.

Stipe: Dismissed.

Mills: It’s a weird record, and it was made at a very weird time. You know, we talk about how with Monster we reinvented ourselves a little bit for that. Up was a complete and utter reinvention because we lost our drummer.

Stipe: We forgot how to talk to each other. And that’s a record that shows that.

Mills: It’s an alienation record. But if the record company wants to [reissue] it, sure, we’ll do it. There was a time at which we’d have been like, “No, I’ve got things to do. I don’t want to sit here and look at the past.” But I think at this point in our lives, it’s okay to take a few minutes and reexamine what we did 25 years ago, how well it holds up, how we feel about it, and how other people feel about it.

Stipe: Disbanding when we did, I think, did a huge favor to fans who stuck with us through the more difficult periods or who came to us during the more difficult periods. We kept our integrity, and we’re now able to look back and go, “That was kind of interesting. Let’s unwrap this and see what it feels like 25 years later.”

[Laughs] Well, therapy session over!

This interview has been edited and condensed.