This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

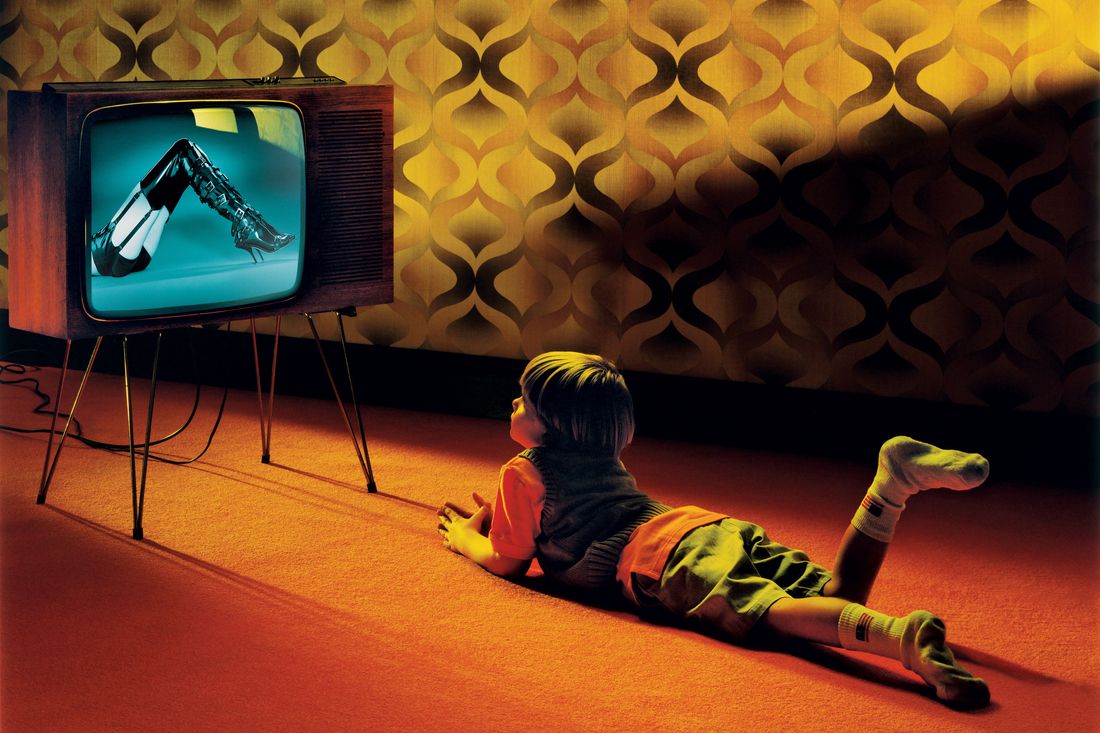

When my daughter turned 3, I started Googling “best first movies for kids.” Surely, someone must’ve already sorted through exactly which of the hundreds of child-aimed movies were most appropriate for a 3-year-old, I figured. Surely, there were lots of lists and suggestions.

There were not. My public library was an undifferentiated shelf of DVDs with Disney logos on the spine. Lists meant for the preschool set seemed to ignore the major developmental differences between a 2-year-old and a 4-year-old. And none of the recommendations broke down titles with the information I really wanted: How scary was it? What was it about, mostly? How complicated was the story? Was it violent? Were there songs? Was it obnoxious in a benign way or obnoxious in a toxic way?

I am a TV critic. I’d spent so long honing my own critical sense of what I thought was good, what I enjoyed, what good could mean. My 3-year-old’s sense of good was very different. Of course it was! But knowing that didn’t make it any easier for me to predict what she was going to like, much less what she’d like that I was also happy to let her watch.

Only one site came close to providing useful, clear, comprehensive guidance, a site I’d never heard of before becoming a parent: Common Sense Media. Its ratings listed TV shows and movies by specific ages (3-plus, 4-plus, etc.), rather than wide, meaningless ranges. The content descriptions warned about scariness, described specific instances of violence, and broke down titles by themes and concepts. Where other lists suggested the usual lineup of Pixar and DreamWorks that I was sure were better for older kids, Common Sense Media proposed Winnie-the-Pooh, Curious George, and The Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland. And there were ratings and reviews for seemingly everything — every Netflix original animated kids’ show I’d never heard of, every one of the six Tinker Bell movies, every spinoff LEGO show, every minor-league Disney property that had come out since my own childhood ended and I stopped paying attention.

I started using Common Sense quite a bit and then I started to see it everywhere. There it was on the “parental info” tab of Target’s website, telling me that How to Train Your Dragon was best for kids ages 7 and older; on the ticket-sales site Fandango, giving me advice about the age appropriateness of The LEGO Batman Movie; on NPR, where I heard coverage of the movies and TV shows Common Sense had picked for its seal-of-approval honorees. Common Sense’s age ratings are licensed to appear on the program guides for Verizon, AT&T, Spectrum, Cox, DirecTV, and Apple TV. When my daughter went to kindergarten, I found Common Sense in the emails I got from her school informing me about a movie that would be shown in class.

Common Sense Media, I came to understand, is the default decider for almost every large-scale guideline about what’s okay for kids to watch. It has 35,000 entries covering TV, movies, books, video games, and YouTube channels and receives about 6 million page views per month. It is a go-to reference for public schools across the country and even writes a digital-citizenship curriculum that is followed in thousands of schools.

As Common Sense Media’s total dominance of the “what’s okay for your kids to watch” space began to fully dawn on me, it also began to feel, not to put too fine a point on it, pretty bonkers. The question wasn’t even what Common Sense was or what its goals were, although I was definitely curious about those things. Rather, its fundamental identity seemed impossible to me: a central deciding hub for what’s okay for all kids, from all kinds of families and backgrounds, that reviewed and rated everything.

While my critic’s brain started whirring along with objections and questions (seriously, who are these people? How do the ratings even work?), I could not escape a simultaneous reality: Common Sense’s ratings were immensely comforting.

Jim Steyer founded Common Sense Media in 2003. He’s a Stanford professor and longtime children’s-welfare advocate. In 1988, Steyer started a lobbying group called Children Now, which pushed for child-appropriate programming on TV. As Steyer tells it, the idea for Common Sense Media came from Bill Clinton, whom he met after Chelsea Clinton became one of Steyer’s students and, eventually, his TA. When writing his first book, an alarmist “how media affects our kids” text from 2002 called The Other Parent, Steyer interviewed the former president about media regulation. “ ‘Jim,’ ” Steyer recalls Clinton saying, “ ‘there’s no other organization that does anything about this, other than the Christian right.’ And he goes, ‘You know, you build big organizations. Why don’t you just do one?’ I’m like, ‘Fuck it, that’s what I’m going to do!’ ”

Steyer, whose brother is the Democratic presidential candidate Tom Steyer, is well connected, loquacious, and prone to telling the kinds of stories that include figures like Clinton or the CEOs of major tech companies. For Steyer, Common Sense’s massive library of ratings and reviews was always meant as an incentive rather than a goal. He intended Common Sense to be mostly an advocacy group, but he looked at organizations like the NRA and the AARP and decided that their success in building membership bases came largely because their members, as Steyer puts it, “get free stuff.” Common Sense’s ratings, what Steyer calls the “Consumer Reports guide for media,” would be the free stuff — something to help the organization establish a powerful lobbying base.

That base eventually materialized. Steyer now spends most of his energies on Common Sense’s lobbying arm, Common Sense Kids Action, which advocates around kids’ safety issues (anti-vaping is its latest crusade), but he’s still responsible for maintaining Common Sense’s prominence and managing its relationships with Hollywood and industry figures. He tells me stories about talking with Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, after 13 Reasons Why came out and chiding him for not considering the show’s damaging subject matter, along with stories about getting calls from creators who have disagreed with Common Sense’s characterizations. Once, he says, Quentin Tarantino called him up to complain about a rating Common Sense had given one of his films.

Is it humanly possible to build a catalogue of 35,000 reviews on identical, fair, ideologically neutral editorial standards? The reviews-and-ratings operation has more than 130 full-time employees, an army of freelancers, and offices in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, London, New York, and Washington, D.C. Because its review library and pool of freelancers are so large, and because Common Sense is so insistent on the idea of neutrality, much of the process of writing a Common Sense review is designed to sand away the distinction of any one reviewer’s individual taste or gut-level response. In order to assign any given title an age rating, reviewers must categorize and quantify the work within several different content areas. Does it have any bad language? How much? How many instances of each word? What words in particular? Does it have any nudity? How much? How many instances? Is there graphic violence? Is it performed with guns or with other weapons? How many weapons? Are there onscreen deaths?

Each “intensifier” contributes to a title’s age rating, and each age rating has its own classification for allowed material. Common Sense’s rubrics allow for the fact that a 13-year-old’s two-out-of-five rating for sex is not the same as an 8-year-old’s. (The 8-plus rating on the 1992 movie Beethoven, the one about the dog, includes a two-out-of-five ranking for “sexy stuff,” as does the 13-plus rating for the CW show Arrow.) The same is true for things like language, consumerism, drinking, drugs, and smoking.

Many of Common Sense’s review categories celebrate values that would be considered broadly progressive: diversity, nontraditional gender roles, understanding marginalized perspectives. But the reviews are written in language that is as inoffensive and abstract as possible, often with a dose of both-side-ism. The rating for 1989’s The Little Mermaid points out that “many think” Ariel’s story is “problematic because it reinforces the idea that a woman should give up her pursuits and opinions in deference to a man.” “Others can put this concept aside,” it continues, “to enjoy the sweetness of the central character and the universal challenges of love.”

Some categories, like “consumerism,” seem less quantitative and are used in occasionally counterintuitive ways. The LEGO Movie gets a full five-out-of-five rating for consumerism because it’s about products. But because Frozen 2 doesn’t promote any consumerist stories within the story, and the characters themselves were not toys to begin with, it gets only one out of five, even though the rating notes (correctly) that there are “countless merchandise tie-ins.”

In speaking with Common Sense staff, it’s impossible to come away with anything other than a sense that these categories and their definitions come from an abundance of good faith. They do not think of themselves as censors. They are truly just trying to help legitimately busy parents make informed choices about how their kids interact with media.

But the fundamental paradox at the center of Common Sense’s mission is what I find most frustrating and most seductive: The act of neutrality always requires defining what “neutral” is. To have a category like “positive messages” at all implies that positive has some specific meaning, and that’s even more obvious for “positive role models & representations.” The messages section for Molly of Denali applauds the show’s “respect for cultural diversity” and “multiculturalism.” On the “role models” section of Finding Nemo, the rating notes that Nemo “doesn’t let his disability slow him down.” I happen to agree with how the site generally defines these categories, although I suspect the relatively black-and-white morality of a 5-year-old’s “positive messages” may get much trickier when I wrestle with the media chosen by a 10- or 13-year-old.

A Common Sense entry does leave some room to reflect the reviewer’s opinion. In addition to the age-rating and content-warning boxes, titles come with a star rating and a field for the reviewer to assess “Is It Any Good?” Those sections can be helpful, but the tonal sameness that shapes the ratings section often drifts down into the language of the reviews. Is there a meaningful difference between Puffin Rock (“Enjoyable to watch”), Super Monsters (“Exceedingly delightful”), and Caillou (“He always gets the life lesson—and viewers will, too”). If these shows are not in your vernacular, let a critic offer her opinion: Puffin Rock is spectacular; Caillou is a nightmare.

Especially for younger kids, reviews tend to focus on the good a show might do — it could teach sharing, it could introduce kids to STEM — rather than the good a show can be. The “Is It Any Good?” section for Shaun the Sheep notes that episodes are “packed with clever humor,” but it’s mainly about assuaging any worry that Shaun’s mild mischief could inspire kids to behave the same way. It does not mention that it’s a fantastically beautiful show and that its clever humor is largely the result of uncommonly witty design. And while the review notes that it will “delight viewers of all ages,” that mild clause understates what a rare, impressive achievement it is for a children’s show to be equally engaging for toddlers, grade-schoolers, and parents. The “Is It Any Good?” review of Wonder Park explains that the movie is “darker” and “more intense” than kids might expect. It doesn’t mention that the movie is also quite bad.

What I’m most struck by, after diving deep into the language and structure of Common Sense’s ratings, is the irreconcilable gap between my critic brain and my parent brain. My critic brain tells me all of this is absurd. We all know that some small group of real people is behind the decision that Frozen 2 be designated as 6-plus and that such a decision is a qualitative one, not just quantitative. And especially when the ratings feel, if not conservative, then at least cautious, Common Sense’s insistence on blurring the distinction between a human response and an authoritative measurement sends up red flares of warning. It almost offends me, or at least the part of me that writes reviews myself, the me that struggles weekly to balance my own response to a TV show with what I imagine other viewers might feel.

It does not offend my parent brain. My parent brain does not care about discussions like “How should a critic respond to art when ultimately all experiences are subjective?” My parent brain values certainty and safety, and it appreciates recommendations from adults who have already watched the best Minecraft YouTube channels and point me toward the ones that won’t terrify or red-pill my children. When my now 5-year-old came home one day mysteriously implanted with the desire to watch “anything on Disney+,” I quickly found the relevant list on Common Sense Media and steered her away from LEGO Star Wars (7-plus) but decided Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends was probably fine (6-plus).

This is also what lots of Common Sense users say. Teachers told me they use it to make a video that will be okay for every kid in the class from all kinds of backgrounds. Parents of children with autism told me they use it to screen for specific content they know will upset their kids. Parents told me they ignore the ratings and just read the comments. Parents told me they ignore the comments and just use the ratings. They also told me stories of failing to check Common Sense Media at their peril and of older children who started using Common Sense Media to argue the case for why they should be allowed to watch something. TV critic Alan Sepinwall told me that, in his family, his wife tends to consult Common Sense Media as a tiebreaker when figuring out what’s okay for the kids to watch, even though, like me, filtering for quality TV content is his job. The reality is that kids are just as inundated by Peak TV as adults are. Common Sense Media is the best option for exhausted, overextended, confused parents wondering what the hell is up with Forky Asks a Question.

Since the 19th century at least, children’s literature has been shaped by the idea that books for kids should be good for them and improve their moral character. It took time for children’s fiction to adopt the idea that it could also be entertaining. The history of kids’ TV and movies has been the reverse arc, starting from a baseline promise to be something to occupy and entertain your children and possibly also teach them the alphabet. The idea that TV could instill values is a relatively recent one, and only in the past few decades has there been enough variety in children’s TV programming that parents can choose the titles that reflect the world we want kids to aspire to and be inspired by.

There are things I don’t want my kids to see yet, but there are also lots of things I want TV to show them: unusual animals, different places around the world, kids cooperating with one another, characters overcoming obstacles. Especially now that there’s so much children’s media available, I find myself longing for the kind of personal, critical voice Common Sense so studiously avoids. I want to know not just if there are strong female characters but also if a show is beautiful, if it’s innovative, if it has a thoughtful aesthetic, what its sense of humor is like.

In other words, TV for children can be both good for them and good. And parents now have enough choice and enough control to aim higher, to set the bar somewhere above “not actively obnoxious.” What they still don’t have are the countless hours necessary to wade through oceans of children’s programming, searching for the few gems. It’s limiting and frustrating that Common Sense Media is the only major operation out there doing the work of sorting through it all, but it’s also much, much better than nothing. And besides, eventually what kids need most are the tools to make their own decisions about what to watch. Common Sense is there for that, too. “I feel like parenthood is basically planned obsolescence,” one parent told me, “so you have to give kids tools to figure things out themselves.”

*This article appears in the December 23, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!