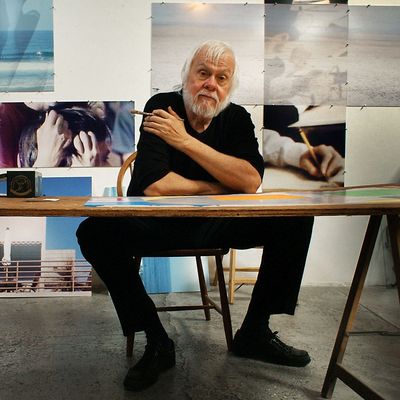

The conceptualist John Baldessari, who died Thursday at 88, spent more than five decades making laconic, uninflected, ironic conceptual art-about-art and art-about-life. The shadow cast by his work is extending still, the orphic aesthetic-intellectual lantern he raised a half-century back beams forth today. His art was metaphysically layered, mystically simple, splendid when it was good, entrancing and gleeful when it was great. This meant photographs of him blowing cigar smoke “to match clouds that are different,” a simple pencil drawing of squiggles and shapes titled Art Lessons, takeoffs on formalism featuring a blue field of sky with three balls thrown into the air to try to get a straight line, and photos of himself waving good-bye to random boats or hitting objects with a gold club. A personal favorite is a ten-part project based on a state map of California that saw him take ten pictures, north to south, of the exact locations where each of the letters fell on the original map. It’s cosmic mapping, truth, illusion, an off-the-chart kind of imaginary freedom.

All of this work was made in the late 1960s and early 1970s when painting had been pronounced dead. It was after Johns, Rauschenberg, Cage, Cunningham, and an onslaught of Pop and minimal art. At the same time the booming art market emptied out and art took refuge in schools and academies. What Baldessari was doing was eventually pronounced “post-studio” art; artists still say they practice this. By the early 1970s, art had gotten fairly airless. Soon, it was pronounced dead. (The art world loves playing coroner and pronouncing things dead.)

Then an act of abnegation and revelation. Baldessari dropped a bomb on himself. In 1970, in a state perhaps of artistic panic and dissatisfaction, he brought nearly all of his previous paintings to a mortuary, burned them, and put the ashes into a book-shaped urn. He called this Cremation Project. Something happened and he knew it. In a letter to curator Marsha Tucker he pronounced it “my best work to date.” This was happening to artists everywhere who were simultaneously starting over, looking for new forms, other rules. Ed Ruscha made books of photographs of gas stations and all the buildings on Sunset Strip. Vito Acconci famously masturbated under a gallery floor. Bruce Nauman videotaped himself walking in strange ways around his studio. Richard Serra threw molten lead at the wall. Eva Hesse made sculptures from funky rope. Sol LeWitt invented instructions for other people to draw his art on walls. Not long after, Baldessari sang LeWitt’s “Sentences on Conceptual Art” to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

Unlike almost all the others, however, Baldessari soon started making paintings again. His early canvases are basically blank except for words. One beige beauty reads, “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work.” Another, “A work with only one property.” Another features grainy black-and-white photographs silk-screened onto canvasses of nondescript street scenes with captions like, “Looking East on 4th and Chula Vista, Calif.” In A 1968 Painting, Baldessari silk-screened an image of a 1968 painting by artist Frank Stella. He’d invented a new encyclopedia of artistic possibilities. And again, he knew this. But now others saw him doing this, too. (Bear in mind that these were his peers mostly. There was no giant art world then, no money, just one new art magazine, Artforum, which imprinted on art like this like a baby duck. All this really made art a beautiful, if insular, hothouse.) These and other Baldessari works are some of the most iconic conceptual and post-minimal art of the period. Most famous of all is the 1971 lithograph I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art, which is a 22-by-30-inch sheet of paper covered top to bottom with that sentence repeated. Every artist would do well not only to take a gander at this minor miracle but to make a copy of it for him or herself. See where it takes you.

Baldessari’s is a brilliant Frankensteinian commingling of the art that immediately preceded him, the stripped-down singularities of minimalism, and the nimbleness of Pop — its absolute infatuation with popular culture. These he passed through a specifically Southern California, though somehow still universal, shredder, spun it in a post-Duchamp cyclotron, placed the results under a microscope, and discovered something that was both larger and smaller than the sum of these parts. Baldessari located an enigmatic realm where the lightness of being, philosophy, and paradox merge. I have invented a formula for myself to describe what he did to use on other art: Take one part art, one part insight, and square them with two parts of something obvious. This arrives at an infinity point I see as art. I write it out as A + I (O2) = ∞. Whatever he did, it not only makes him the most widely available post-minimal conceptualist but puts him among the most influential artists of the second part of the 20th century.

By now more than four generations have passed through the gates of art that Baldessari revealed. One of Baldessari’s former students, David Salle, once said because “generations of artists” were given such wide permission to make “dumb stuff,” and it’s “largely John’s fault.” Salle meant this lovingly. But this love also mutated into reams of hackneyed, bad (boring) conceptual art.

I have a soft spot for one lesser-known, very early 1963 photographic work in particular. I experience it as a personal memory-theater of solitude and musing, life as a long-distance truck driver, stuck in my own head but looking for acts of aesthetic clairvoyance. This work consists only of a grid of 32 small color photographs. It is titled The Backs of All the Trucks Passed While Driving From Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, California, Sunday, 20 January 1963. Each picture is just that — the back of the trucks. Drop-dead simple, self-explanatory, brave, mortifying, dotty, transitory, rhythmic, reiterative, singular. In it I see the American road, pining, making things of nothing, making nothing of something, shifting vision, focus, an astronomy of everyday life. In this wonderful piece I see the openness of art, Baldessari’s receptivity, the sight of an artist exercising what D. H. Lawrence called “insatiable American curiosity.”