Spoilers ahead for I Am Not Okay With This, the comic and the show.

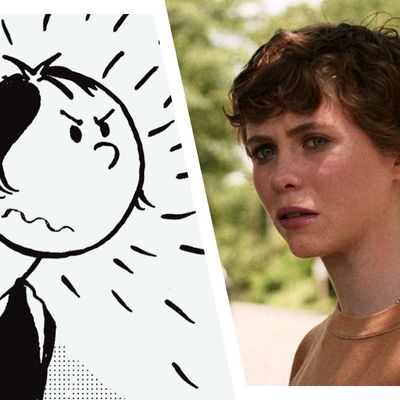

Charles Forsman is an unlikely cartoonist to find success in the world of TV adaptations. His extremely dark graphic novels are characterized by a stripped-down art style and stories focused on feeling over plot, but his work resonated with writer-director Jonathan Entwistle, who adapted Forsman’s The End of the Fucking World into a Netflix show. After two seasons of that twisted story of teenage rebellion, Entwistle returned to Forsman’s work for I Am Not Okay With This, a new Netflix series that also explores the trauma of adolescence, but this time with a superpowered twist: Syd (It’s Sophia Lillis) is a teenager grieving her father’s recent suicide, and her emotions manifest in devastating bursts of psychic power that she can’t control.

With I Am Not Okay With This hitting Netflix this week, in a form that takes visual as well as narrative inspiration from his graphic novel, Forsman spoke with Vulture about his deeply personal connection to the book, and how the series embraces and diverges from his story. (If you haven’t read the book or seen the show yet, consider skipping the very last question.)

What is it about Jonathan Entwistle’s perspective that aligns with what you put on the page?

The way he’s talked about it, he sees my work as already storyboarded out. You can really see that in The End of the Fucking World quite a bit. Some of the panels are exactly replicated on the screen. The style of these two books is very — it’s that Scott McCloud thing, where they are simply drawn characters, so it’s very easy for readers to imprint their own experience and emotion onto the characters. There’s an element of that that attracts Jon to them, and he can easily fit his style and what he creates on top of it.

The design for Syd is very Olive Oyl, and there’s a lot of Popeye in your work in general. What is it about that style that appeals to you?

E.C. Segar, who created Thimble Theatre and Popeye, is one of my favorite cartoonists. A long time ago I used to get really upset with myself for not having a defined style that I felt was my own, so I decided that I was gonna lean the other way and use style as costumes, depending on the story I was telling. For [I Am Not Okay With This], I was looking at old Popeye strips and the thing that attracts me to it is that it’s sort of like vaudeville. Watching a play on a stage. The way he stages everything is side-to-side, and you can tell in that first chapter that I’m really heavily using all that stuff. When I start a project, there’s so many little decisions you have to make. Setting up the rules and guidelines, I used Popeye strips as my guide for how to tell the story. It takes a lot of the decisions away, and it really helps to get one moving onto a story if you have the road laid down.

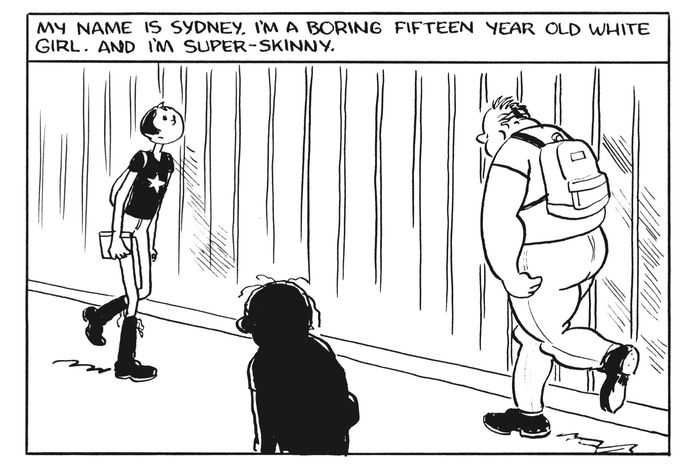

Syd walking through the school hallway at the very start is one of the few points in the comic where you get an angled perspective. Are those perspective shifts a deliberate choice on your part?

Yeah, as the book goes, you see me changing it up. It depends on what I want to show. I’m not very conscious of it. That’s part of comics: It’s a lot of doing the same thing over and over again. For these types of stories, I don’t want it to be flashy and I’m not concerned with it being beautiful. But you still have to make it interesting, design-wise. Even if it’s just people talking or walking down a hallway, so that it’s not boring to look at. There’s a lot of design that goes into each panel, but I don’t think people talk about that a lot. There are so many different things we’re using. It’s not just drawing and writing. Design is a big part of it, placing things on a page that are pleasing to the eye.

Did you have a journal like Syd when you were a teenager?

I tried. I was super unmotivated, I probably wrote two sentences and gave it up. If we got writing assignments in English class to make up a story, that was when the glimmer of creativity popped out. That was way more interesting to me than writing down my life details. But I do put a lot of personal stuff in these stories. Even when I’ve tried to make auto-bio comics, it’s the same feeling. I hate it. I give up. It feels gross to me, and I have no motivation to do it. I’m too concerned with the truth then. When I’m depicting real people, I feel too beholden to tell the truth, so it’s less interesting for me to make.

Having an element of fiction, and in the case of I Am Not Okay With This, a supernatural element, can break a barrier that you might have when working strictly autobio. It can open you up to be more honest than you would be if you were actually sharing your own story.

Totally. This story is actually the most personal to me. I lost my dad when I was 11, so Syd’s relationship with being a teenager and dealing with that loss and emptiness is a huge thing. When I sat down to read the scripts for the show, I was in tears. I had forgotten how personal some of that stuff was. And seeing it filtered through other writers, it still came out to me very personally. It’s intense for me to watch, because it feels very close to me.

When I read your work, I feel like there are a lot of distinct scenes where you learn about the characters in that moment, but you don’t spend a lot of time on exposition, which is where the TV show expands.

I’m a huge fan of not doing world-building or exposition. My eyes glaze over when I see it. I’ve always loved the idea of dropping in on conversations and letting the reader put the puzzle together by hearing characters talk. It goes back to Thimble Theatre. These are very short chapters in this book, it’s not a lot of space to do long spread-out explanations. It’s cartooning: distilling everything down to what you need to create a feeling. The only way I’ve learned to do that is to do it scene by scene, chapter by chapter. It’s not like filming, where you can shoot a bunch of footage and edit it down. I could just draw pages and pages, but I don’t have the motivation for that. I try to pick what I need.

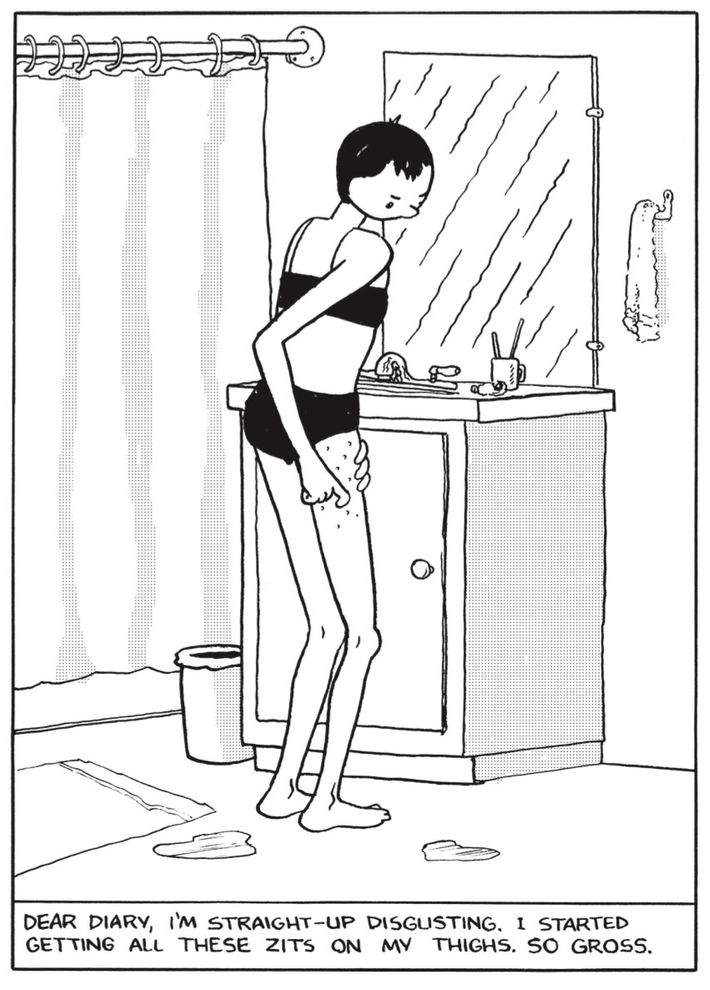

One of the most direct scenes pulled from the comic is Syd examining and popping the pimples on her thighs. It’s not quite body horror, because it’s something people deal with all the time, especially when you’re a teenager. But it’s gross. I knew there was a close-up coming and I was dreading it the entire time. And the zits end up being an important part of Syd’s relationship with Simon, where their imperfections are what bring them together.

[Laughs.] I had zits on my thighs when I was a kid. I remember feeling so disgusting and grossed out by them. Panicking because I don’t know what to do with these things. I don’t see a lot of people putting something like that in their stories, but it’s an important detail to who Syd is. It’s what life is about. There’s disgusting things. I love that you were dreading that. [Laughs.] I had the exact opposite reaction when I saw the scene of her picking at the zits. I threw my fists in the air and cheered because I was very happy they threw it in there.

Zits are the adolescent metaphor. Your body’s freaking out, and a zit happens because there’s this built-up gunk in your skin. And Syd has this whole other thing where her power gets released when she’s emotional. It’s like the emotions are the puss in her brain and she gets it out with explosions of uncontrollable psychic power.

With her powers, I came up with the idea after watching Scanners for the first time. The best X-Men movie is Scanners. I wanted to tell a teenage story about anxiety but have a weird power element to it. The focus wasn’t the power so much, but the show’s leaning into that. It’s more of a background element, her anxiety and the shadow following her. That’s one of the biggest changes.

The show’s final scene is pulled from the comic, with one massive change: Syd doesn’t use her power to make her own head explode. Why did you end the story that way? Did you know from the beginning that was where Syd would end up?

Not really. Usually when I write, it starts out pretty improvisational. I have rough ideas of what I want to do, but I’m less concerned with plot and where everything’s going and more concerned with creating a feeling. It was the last few chapters when I knew where it was going. It’s something I still wrestle with. I feel like the instincts that got me to that point, I have to listen to those voices inside me and put it on the page. That’s the thing that feels satisfying and what I have to do.

I’ve been called out for that ending. I’m sure people have experienced suicide in their life and to see that depicted, some people think it’s irresponsible and I totally get that. In the new printing of the book, I added information in the back for a suicide hotline. I wasn’t ready to change the ending. Growing up in the ’90s, I was a big fan of Kurt Cobain, so I’m super conscious of that stuff. I don’t want kids reading this and thinking that’s an answer, because it’s definitely not. But within the story, which is fantasy, I thought it was a fitting end that she would relieve her pain with the very powers that were causing it.