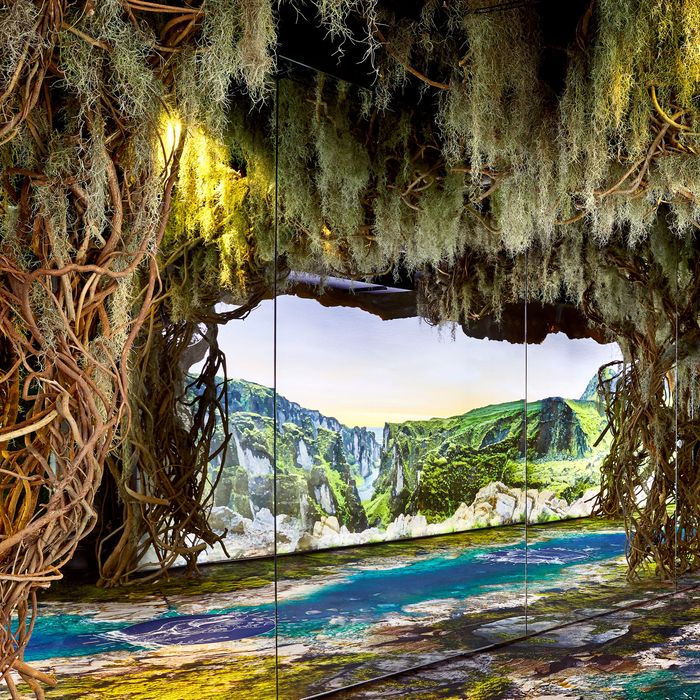

Jenny Offill is wandering through Arcadia Earth, an “immersive, augmented reality journey through Planet Earth” in downtown Manhattan — the museum’s words, not hers. She chuckles at the broad advice plastered on the walls (“Our choices matter!”), wryly countering with the most damning facts she knows about the climate crisis. (Soon, we’ll have so many jellyfish in our acidic ocean that we’ll need to start eating them — or turning them into tampons.) A disturbingly soothing voice trickles in over the loudspeakers, offering suggestions for sustainable clothing fibers. Offill shakes her head. Tiny individual choices are not going to turn the planet around and send new greenery shooting up across the continents, even if we can convince people to undertake them. “You could move through this exhibit,” she laments, “cross everything out, and just write ‘Take collective action.’”

Offill is an expansive presence, constantly craning her neck and swiveling her head to take in what’s around her. Where her novels are pared down, like modernist rooms in which every vase, chair, and lightswitch is considered, textured, and weighty in your hand, in person she is a teetering pile of books overflowing with feathery notes on ripped paper. She bubbles over with reading recommendations — Paul Hawken’s Drawdown, David Wallace-Wells’s Uninhabitable Earth, a forthcoming book called Notes From an Apocalypse by Mark O’Connell — cites study after study, and offers little nuggets of information that didn’t make it into her newest novel. (She recalls one Australian researcher who, upon learning just how high ocean temperatures will rise, had to excuse herself from a meeting to vomit in the bathroom.)

That novel, Weather, which recounts in dotted, thorn-sharp fragments one woman’s reckoning with our condemned-to-death world, is packed with plenty of fear-inducing information. “There are 6,000 miles of sewer in New York City and all of them lie well below sea level”; the superrich are “buying doomsteads in New Zealand”; soon we may not have apples — “apples need frost.” Over the course of a few years, leading up to and then beyond the 2016 election, the protagonist, Lizzie — a Brooklyn-based librarian, wife, and mother — grows increasingly attuned to our planet’s grim plight, and slowly moves through what you might call the Five Stages of Climatic Grief: ignorance, disbelief, worry, heightened worry, and then, well, you’ll have to read to find out.

Weather, out this week, sent me into several small tailspins an hour, googling citizenship processes for nations with better climate prospects and viciously circling paragraphs about how to prepare children to milk goats and churn butter. “I know all this because I did it, too!” Offill yelps in communion, over juices at a Mexican restaurant a few blocks away from Arcadia. I wrote little W’s next to every section that caused me worry. By the end the book looked like Cy Twombly had attacked it with graphite.

In a way, that confrontation of fear may be the response she was hoping for. Throughout the novel, she lets Lizzie simply imagine all the versions of the future that could come to pass. The future is a dark closet with the door slightly ajar. The monster is inside it, whether we choose to look or not.

The 7-year-old narrator of Offill’s first novel, Last Things, is given a cosmic calendar that includes a sequence of species vanishing from Earth. “My mother said that stones were last things and would be around long after people were gone,” she explains. “Other last things were oceans, metal and crows.” You can draw a line straight from that book, published 20 years ago, to Weather — from a child trying to make sense of collapse to a mother who can’t decide if it’s possible to make sense of collapse.

Formally, Weather is closer to Dept. of Speculation, Offill’s second novel and the break-out critical hit she published in 2014. Both novels intersperse narrative momentum with anecdotes, quotes, lists, and, in the case of Weather, a series of email Q&As. It abandons traditional storytelling just as the arc of humanity is hitting its denouement. Offill first gathers all the material and then assembles. “It’s like if you had a jigsaw puzzle, and you knew all the pieces were there, but you didn’t have the box, and you didn’t know if it was a picture of a forest or a picture of kittens and jellybeans.” Or a planet on fire.

Just around the time Dept. of Speculation was gathering accolades, Offill read a New York Times profile of Paul Kingsnorth, the founder of the Dark Mountain Project and a newly reluctant environmentalist. A former editor of The Ecologist, Kingsnorth had essentially given up on the idea that we could save the planet from the coming heat and meltdown. He had established Dark Mountain to, he writes, “look over the edge, face the world that is coming with a steady eye, and rise to the challenge of ecocide with a challenge of its own: an artistic response to the crumbling of the empires of the mind.” Offill had been suppressing her dread about the warming oceans and falling trees and lifeless coral for a while, but this tipped her beyond what she calls “twilight knowing”: “You know something but you don’t really want to know it. You know it but you don’t look any further. You know it but you still look away.” She wanted to capture that feeling in her next protagonist: the tip of the seesaw from the not wanting to know to the realization that you absolutely must.

Then, after the 2016 election, she read an essay called “Stop Making Sense, or How to Write in the Age of Trump,” by the Bosnian-American novelist and memoirist Aleksandar Hemon. He implored writers, she says, “to think about what it means to talk about what it feels like right now.” She quotes a large chunk of it to me:

The necessary thing to do is to transform shock into a high alertness that prevents anything from being taken for granted — to confront fear and to love the way it makes everything appear strange. Love the new frequencies; what is noise now will be music late … What I call for is a literature that craves the conflict and owns the destruction, a split-mind literature that features fear and handles shock … America, including its literature, is now in ruins.

Until she read this, Weather was headed for a more classical narrative arc. “But that didn’t feel very true to me,” Offill explains. She needed, she says, to toss out any notes of triumph in Lizzie’s story. Early on, Lizzie takes on work answering emails for her mentor Sylvia, an enigmatic professor who hosts an anxiety-preparedness podcast brilliantly named Hell or High Water. “What will be the safest place?” a crowd of rich dinner companions asks Sylvia. They are searching for a ticket out of the apocalypse. “You’ve interviewed everyone. Is there any consensus? Any clustering patterns of these scientists and journalists?” Sylvia doesn’t respond.

Later, Lizzie mentions that she’s been considering buying land somewhere for her son and niece, “that if climate departure happens in New York when predicted …” she trails off.

“‘Do you really think you can protect them?’” Sylvia asks. “‘In 2047?’” Lizzie looks at her. “Because until this moment, I did, I did somehow think this.”

That date, 2047, had me clutching my bedsheets at night, plotting how to build a homestead on a lot with a freshwater source and keep it entirely off the grid. In that year, my now 3-year-old will turn 30. Her adulthood will exist almost entirely in the “After” scenario for our planet. Like Lizzie, until recently I’ve been fairly certain that with enough money and a remote, well-stocked and fortified cabin, I can keep my daughter alive — if alone — through the planet’s meltdown. I want to know: Did Offill view the book as a way to jolt readers into action?

“If I wanted to write a call to arms, I would have written a nonfiction book,” Offill says. Weather isn’t a piece of climate propaganda or the equivalent of a proselytizing nutter come knocking on your door. “The language of activism feels very earnest and boring to me,” she adds. She also didn’t want to write a dystopian novel, “the way that we as writers have been dealing with this ambient dread” for years. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag wrote that describing horrifying realities, like war, often does not have the intended effect. “For a long time,” she explained, “some people believed that if the horror could be made vivid enough, most people would finally take in the outrageousness, the insanity of war.” Picturing our dystopia isn’t enough. We need to own that one day we will live in it.

The call Offill heard was “towards feeling this emotionally.” Doomsday texts roll out every few months. Museums pop up in downtown Manhattan to guide us on VR journeys through our drowning planet. But despite increasingly dire climate news, the worry is a restricted emotion, kept closeted as if contagious. Weather asks the question, what if we all just let it spill out, and revelled in the relief that comes with acceptance?