The only surviving image from the world’s first film adaptation of Little Women doesn’t reveal much: A group of young women, dressed in gowns, mingling with some men beneath a chandelier. It might be the pivotal party scene from Louisa May Alcott’s novel, where our writerly heroine Jo March meets her wealthy neighbor Laurie. But good luck parsing out who’s who. (Could that be Jo’s sister Meg, near the center, in the flat shoes?) Rendered in such grainy black-and-white, the still looks to be a relic from the actual Civil War era, though it dates to 1917.

Fans who have been won over by Greta Gerwig’s take on Little Women — or by previous iterations, be it the 1994 adaptation by Gillian Armstrong or the Depression-era classic starring a young Katharine Hepburn — might be curious to see the film, the first in a long lineage. But they can’t. The movie, save for this one surviving image, has been forever lost to the sands of time. Poof. Gone. In fact, it’s unlikely that any living human has seen all seven film adaptations of Little Women, because the first two versions, silent films released in 1917 and 1918, respectively, are simply considered “lost,” unpreserved and unavailable in any known archive or collection.

As a compulsive completist, I found this revelation startling: How could this have happened? Where’d the movies go? And will they ever resurface?

As it stands, little is known about the first ever Little Women movie. Oddly, this was a British adaptation of the classic American novel, directed by Alexander Butler, a prolific British director of the silent era. “It probably would only have been shown in England,” says Ed Lorusso, a film historian who has produced nearly a dozen silent-movie restorations, and who revealed the rare still on his blog Silent Room. He suspects that the international staging was a way to skirt the Alcott family’s reluctance to sell the film rights: “My guess is they probably did it [in England] because they didn’t have to pay. The copyright may only have been an American copyright. Who knows. There’s almost no information anywhere on that film.”

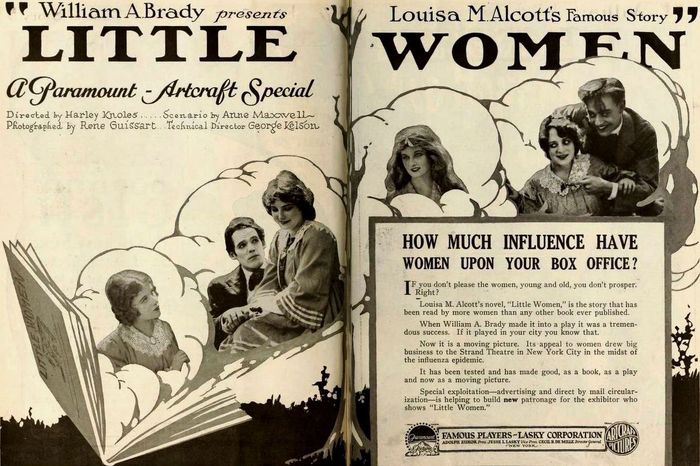

The next Little Women adaptation was an American one, and a well-promoted affair. This silent film premiered in 1918 and received a wide release in early 1919, according to IMDb. We know the producer was William A. Brady, who had a long history with Little Women, having produced it on Broadway, and the director was Harley Knoles, who had worked on more than a dozen films for Brady’s production company. The prolific silent actress named Dorothy Bernard starred as Jo. “It was a big film,” says Lorusso. “It got tons of publicity. There’s all kinds of promotional stuff in the literature of the day — it was the 50th anniversary of the book.”

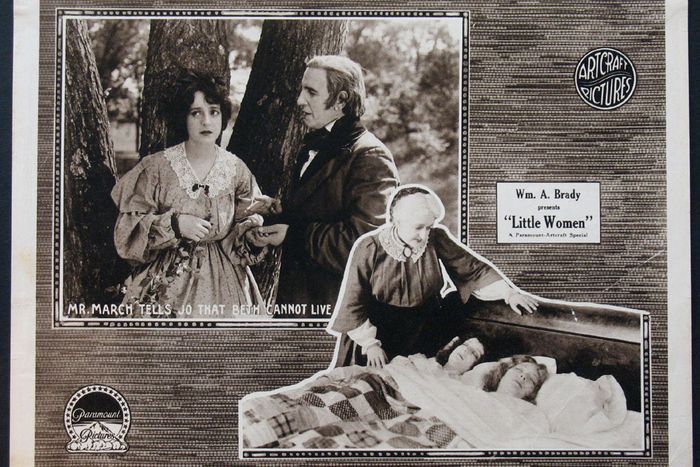

Kevin Brownlow, a prominent film historian and world authority on silent cinema, says he can trace the film vis-à-vis its 1919 release. “This one, according to the invaluable AFI catalogue, was shot in and around the Louisa May Alcott home in Concord, Massachusetts. The home of Ralph Waldo Emerson was also shown. Conrad Nagel was in it as Laurie — he was soon to be a major MGM star.”

Although Alcott had long since died, Lorusso says her family was more intimately involved in the 1918 film than any other Little Women adaptation. As he notes on his blog, the usually copyright-cautious Alcotts made an exception for Brady provided they had final approval on casting decisions. They even allowed the film to be shot on location at Orchard House, Alcott’s long-preserved home. “Everything was filmed there, under the watchful eyes of the Alcott family,” Lorusso says.

The movie was distributed by Paramount and seems to have received robust support. A 1918–1919 edition of the Paramount and Artcraft Press Books boasts that Little Women is “a splendid screen subject” and “almost certain to insure record business at any playhouse.” The book urges theater owners not to miss out on showing the film: “It is safe to state that nine out of every ten women and girls in your town have read this idyllic story of home life during the period of the Civil War … Every woman who has read this notable book in her girlhood will see the picture again at your theatre. Every mother will want her daughter to see it.”

Was it a hit? Who knows. “Trying to find box office [numbers] is almost impossible because nobody really tracked it back then,” Lorusso says. But Beverly Lyon Clark, in her book The Afterlife of Little Women, writes that the film seems to have been “reasonably successful,” even in the midst of an influenza pandemic. One Philadelphia theater continued showing the film a second week because thousands of eager moviegoers hadn’t gotten tickets the first week.

Critics were enthusiastic, Clark notes. Variety praised it as “a picture out of the ordinary,” highlighted by the “good looks and quaint dresses” of its stars. Motion Picture Classic declared it “a delightful picture.” In a more measured review, the New York Times described the acting as “satisfactory” and praised the film’s “charming glimpses of the [Civil War] period.”

And yet, despite such a positive reception, the film didn’t survive the transition to talkies. There’s no record of it having been rereleased anytime after 1919. Brady shut down his film-production company around 1920. “I have a feeling that when he closed his production company, they probably just dumped the films,” Lorusso says. Today there are listings for the 1918 film on eBay and Amazon Prime, but those are phony. (As one Amazon reviewer protests: “This is 1950 TV drama, not 1918 silent picture.”)

“Little Women never reappeared after its initial run,” Lorusso confirms. “It’s just gone. Nobody knows what happened.” Logically speaking, it’s unlikely there remains any living person who saw this film more than a century ago. “I mean, it was 102 years ago,” he adds. “Even a 5-year-old seeing the film would be 107 now.” Nonetheless, I emailed about a dozen nursing homes in New York and Los Angeles with the hope of tracking down a 107-year-old Little Women fan. Alas, my search yielded zero results.

The circumstances surrounding the first two Little Women films are tragic but not unique. The Library of Congress estimated in 2013 that a staggering 75 percent of silent films are lost, presumably for good; many exist only in fragmentary form. In a separate study, The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929, historian David Pierce concluded that only 14 percent of the nation’s silent feature films exist today “in complete, 35 mm copies.” The Birth of a Nation notwithstanding, survival rates from the 1910s tend to be particularly low.

Indeed, the history of early cinema is scattered with the bones of lost movies. The very first Great Gatsby adaptation? Lost. Alfred Hitchcock’s The Mountain Eagle? Lost. (There is even a Best Picture nominee, 1928’s The Patriot, that’s mostly lost, though portions survive.)

Fans of silent cinema have grown accustomed to this particular anguish. Nora Fiore, a writer and classic-film enthusiast known for her film blog, the Nitrate Diva, tells me she keeps a “hope they find it someday” list of lost films in her head. “One that I would come running across the world to see if it ever surfaced is Erich von Stroheim’s The Devil’s Pass Key,” Fiore says. “His films are just so interesting and decadent and kind of amoral and sexy in this way nobody else was doing at the time.”

The glut of lost films means that large swaths of film history are forever irretrievable. There are some actresses from the silent era — like the mysterious and macabre Valeska Suratt — whose entire filmographies are lost to history. The contributions of women behind the camera, too, are easily forgotten. Lillian Gish’s only film as a director, Remodeling Her Husband, is lost. Some scholars estimate that roughly 50 percent of silent-era films were written by women. “This was a time that was especially exciting for women contributing to a new medium that hadn’t yet decided to lock them out of creative positions,” Fiore says. “And this is the era that got hit the hardest by lack of preservation and decay.”

In an email, film historian Brownlow identified five major causes of silent films becoming lost. They are, in his words: “destruction by studios through incineration to recover silver and to clear shelves for more commercial productions; chemical decomposition of nitrate stock; being sent out on release, and abandoned at the end of the distribution trail; theft; and fires (nitrate was so inflammable it could burn underwater).”

Implicit in his list is the sad reality that studios weren’t able to grasp the historic significance of their own films. “It was pretty much a throwaway kind of thing,” Lorusso says. “You do this little 20-minute film, you’d show it, you’d make your money, and on to the next one. It wasn’t seen as art that needed to be preserved.” When the talkie era arrived, “virtually nobody considered that silent films would have any value.”

Some stars, like Mary Pickford, took an active role in archiving their own work, but they were exceptions. Often, studios would deliberately destroy the silent version of a film when they released a talkie version.

The good news? The lost Little Women could conceivably rise from the dead, particularly given the interest generated by Gerwig’s film. “As we always say, a film is only lost until it’s found,” Lorusso says. “Stranger things have happened. There are certainly any number of famous films that were considered lost and all of a sudden a copy shows up.”

In many cases, films presumed lost show up in foreign archives because of title changes. In other words, 1918’s Little Women may have been shown in Europe under a different title, Lorusso speculates. “So the film is sitting there under some other title, and somebody doesn’t even know what it is until they take it off the shelf and look at it.”

Consider, for instance, the story of the 1916 Sherlock Holmes. For nearly a century, this early adaptation of the mystery franchise was presumed lost. In 2014, a nitrate dupe negative of the film was miraculously discovered in Paris, and the film was subsequently restored. In 2015, Fiore attended one of the first North American screenings of the restoration and found it to be a magical event. (The movie itself, she says, turned out to be “just a charming film.”)

“It’s almost like a mystical experience,” Fiore says. “This time that was lost, coming back to you. These people who are no longer here, these things that no longer exist, these image captures. And it’s back. It’s saved.”