Alan Yang’s first feature film, Tigertail, which comes out on Netflix April 10, began as a file saved as “FAMILY MOVIE” on his computer, dated August 14, 2016. But when he read the story again later, he shelved it. “I just said, ‘This isn’t it, man. This is a B. It’s because I don’t have a personal enough connection to it,” remembers Yang. So he started writing again. A lot. He wanted to tell a sprawling, multigenerational Asian-American tale, and ended up writing a 250-page script with multiple points of view that he eventually whittled down into one central character, Pin-Jui, played by Tzi Ma in the present and Hong-Chi Lee in the past. The young Pin-Jui lives and romances in Taiwan, before eventually moving to New York City. It is what Yang calls his “fever dream” of how he imagines his own father’s immigration story. “The movie is kind of my dream of my father’s dream of his past,” says Yang. “It’s emphatically not his story in some ways.”

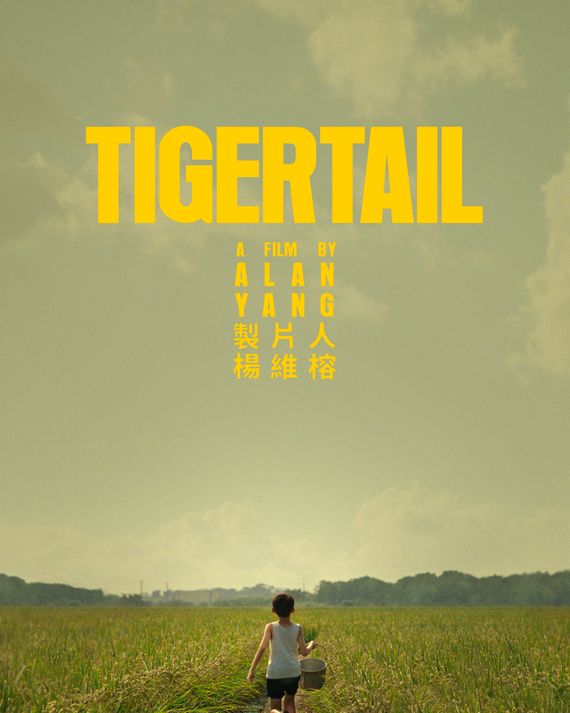

As part of an exclusive release of the trailer and poster art for Tigertail, Yang spoke with us on the phone about how the film changed his relationship with his father, gave us a snapshot of his quarantine life, and discussed why John Cho didn’t make the final edit of the film.

How have you been spending the time during the pandemic?

There’s been basically more cooking and cleaning happening in my apartment than has ever happened in the whole time I’ve lived in my place here. Grocery shopping. We’ve been cooking some decent stuff. I’m not a very good cook, but I’m learning. I do feel relatively healthy-ish because maybe I’m not eating so many restaurant meals. You know I love going out to eat. It’s obviously a shame what’s happened to all the restaurants and the whole industry.

Are you practicing social distancing right now in Los Angeles?

Yeah, 100 percent. It’s basically only leaving to go to the grocery store or go on a walk. Actually, I take that back. My dad lives in Pasadena. To me, that’s the person I’m most worried about. He’s obviously a little older and has a preexisting condition. Yesterday my girlfriend and I went and gave him some hand sanitizer and gloves. We went and dropped it off outside his house and then spoke to him briefly from like 20 feet away. It’s so crazy that’s what you have to do now.

Did your relationship with your father change during the course of writing and making this film?

Yeah, it really did. My relationship not only with him but with my entire family; and my own understanding of what it meant to be Taiwanese and what it meant to be Asian all changed over the course of the last five years. Where I grew up, being an Asian person was something that was almost seen as an impediment when I was a kid. It was an impediment to fitting in. It was an impediment to seeming “normal.” It just sets you apart. When you’re a little kid, being set apart is not necessarily the thing you want. It’s not necessarily a strength. But when you get older, and especially when you’re lucky enough like I have been to be able to start creating your own movies and shows, the stuff that sets you apart is the stuff that’s gold. That makes you unique. Being Asian-American is certainly a part of who I was, whether I wanted to come to terms with that or not.

A very simple example of that is, I hadn’t gone back to Taiwan since I was 7 years old. It’s the place my parents grew up. My sister had gone back many times; in fact, she lived there for a summer. She took Mandarin in college and could speak it, whereas I couldn’t at all. I just had no interest. I wanted to prove that I could write all kinds of stuff and be a comedy writer, basically that I could make it in a mainstream way.

What changed?

One of the most seminal moments in the conception of the movie was when I took a trip to Taiwan with my dad. I happened to be in China at the time working on something else. This must have been about four years ago. He showed me around. That was the first time I’d been back since I was a kid. I heard him speak Taiwanese to cab drivers. We took the high-speed train down to the middle of the country, to a really rural part of the country, and he showed me where my grandma was laid to rest, which is in the movie. He showed me the factory that he used to work in with my grandmother, at the same factory we shot in the movie. I just didn’t have any idea about his life. Also, not to spoil too much of the movie, but it was an inspiration not only for the beginning of the movie but for the end of the movie, where two of the characters take a trip around Taiwan and ride the high-speed train and all that stuff. It was very evocative of my own trip there.

What was it like working with your father on the film? My understanding is that he does the voice-over that bookends the film.

Yeah, it was an idea I had partway through postproduction, where I wanted that voice to be almost haunting in the sense of how matter-of-fact it was. I just had a hunch, so I got my dad in and asked if he would be willing to do the voice-over for a couple hours just to see. I told my editor, I was like, “Let’s just see what happens. This could be a disaster. It might not work at all.” But I knew my dad has a deeper sort of timbre. He has a gravitas to his voice. He also had a Taiwanese accent. He was born in Taiwan; he has the real-deal accent. He really did a good job. I had him do a bunch of different takes, but he came in pretty close to what I wanted almost immediately.

It was really meaningful for me, obviously. I think it’s very effective, but it was a meaningful moment for both of us. I thanked him. Afterward, we were texting at some point. I was like, “Oh, thank you so much. You didn’t have to come in and do that.” He’s like, “Oh, no, no. I’m retired. That was the best moment of my year. I got to go into a recording booth and read these lines. My son is the director, and he’s directing me how to read stuff. I couldn’t be more proud.”

My understanding was that John Cho was supposed to be in the film. What happened?

He definitely shot some stuff with us. It was great. He delivered an amazing performance in the movie. As happens sometimes in the course of editing, the movie tells you what it wants to be. It killed me to do it, but his character was in some of the modern-day scenes, and we didn’t end up using those scenes. I called John basically as soon as I was thinking about making that decision. He was in Australia filming Cowboy Bebop. We had a fairly long, meaningful conversation. He was so supportive and understanding. I’ll always remember that conversation.

He told me that he had a great time working on the movie. In fact, he was doing scenes in this movie that were scenes unlike he had done before in his career. I know how long he’s worked and how much he’s meant to the Asian-American community, so that meant a lot to me. He’s an executive producer in the movie. The movie would not have been the same without his energy and force behind it, so I’m incredibly grateful to everything John gave to the movie.

I guess that’s what killing your darlings means.

Yeah. It’s like I said, it happened in the writing process as well. Sometimes it happens in the editing booth, but it’s really figuring out and drilling down on what the heart of the movie is. It really is like, Okay, well, how do I make sure every scene in the movie is pulling toward the ultimate goal? That is where some of the most difficult choices have to be made.

Did you have a pretty good grasp of your father’s immigration story, and does the movie hew closely to it?

It’s actually kind of a strange answer. I did not have a very clear picture. I did ask him some questions, but I didn’t really want it to be word for word. I almost wanted just enough information to come up with something fictionalized but not so much that it ruled out ideas that I had, because the way I’ve been describing the movie is kind of my dream of my father’s dream of his past. It’s emphatically not his story in some ways.

It’s idealized, right? If you look at the way we shot Taiwan and the way we dressed the characters, and how full of passion and charisma Hong-Chi is in the movie, and how charming Yo-Hsing Fang is, that is all my fever dream of my dad’s stories melded with some Wong Kar-wai and some Hou Hsiao-Hsien, so it’s not exactly what happened to him. Obviously, a lot of that is also metaphor. I’ll be totally honest, I don’t have a word-for-word history of either my dad’s or my mom’s experience. I’m sure if I were to tell it to you right now, it would be wildly different from their own versions.