This New York Magazine story was originally published on September 3, 2019. It is being republished here following the release of Netflix’s Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.

Joe was born with an unusual last name, rough on the tongue: Schreibvogel. People were always getting it wrong or using it against him, so he changed it, and changed it again, until he finally slipped free of it altogether. Over the years, as he amassed a string of husbands, he borrowed their last names, calling himself first Joe Maldonado, then Joe Passage; when he did his magic shows, he sometimes went by Aarron Alex or Cody Ryan; when he was filming his reality show, he called himself “the Tiger King”; but the name he was best known by, as a zookeeper, country-music singer, stunt politician, and amorphous internet celebrity, was Joe Exotic.

Joe grew up on a farm in Kansas among creatures of the barnyard variety — horses, cows, chickens, dogs, cats — as well as the varmints he and his siblings sometimes brought home: baby antelopes, porcupines, raccoons. Joe was born into the middle of the pack with two brothers and two sisters, and he often felt that his cold Germanic parents viewed him as a source of farm labor rather than a child. He recalls that no one in his family ever said “I love you” to each other.

Humans, Joe learned early, can be the cruelest of all God’s creations.

When he was 5 years old, he says he was repeatedly raped by an older boy. This happened in his own home. He vividly recalls how a drawer in the bathroom could be opened to prop the door shut.

Joe chose to give his love to animals. He became the president of his local 4-H chapter, where he raised show pigeons. He took in ground squirrels and raccoons and kept them in cages until, his mother says, you could barely get through the back porch. (She put her foot down when he started bringing home snakes.) Joe dreamed of being a veterinarian. On afternoons when he wasn’t pulling weeds or doing chores around the farm, he would take his BB gun and shoot sparrows. Then he would collect used medicine bottles, left over from treating the cows, and fill them with colored water so he could “doctor” the birds back to health.

Joe’s mother likes to say that Joe’s father, whom people called Francie, had “itchy feet.” When Joe was 11, Francie decided he would rather raise racehorses than crops, so his family began roaming north and south along the plains from Kansas to Wyoming to Texas. Few of Joe’s classmates from those years remember him, and his photo is often missing from his junior-high yearbook. In high school, he got bullied by the jocks because he preferred to hang around with girls. In retaliation, he says he sprinkled roofing nails all over the school parking lot and popped the tires of a hundred cars. “I had to get a job and pay for them all,” he later recalled. “But they never fucked with me again. Never.” (Those who knew Joe at the time, including the school’s principal, do not recall this event ever taking place.)

After graduation, Joe talked his way into becoming the police chief of a tiny, crumbling Texas town called Eastvale (population 503). He lived with a girlfriend named Kim but also explored Dallas’s gay nightlife. Overcome with shame one night in 1985, which Joe would later refer to as “the bad year,” he says he attempted suicide by crashing his police cruiser into a concrete bridge embankment at high speed. Residents of Eastvale do not recall this crash, nor do Joe’s family members, though Joe does have a photo of the demolished car, which he offered as proof.

In Joe’s mind, at least, the crash was the beginning of Joe Schreibvogel’s rebirth. He says he ended up with a broken back, spent 57 days in traction in the hospital, and then moved down to West Palm Beach, Florida, to participate in an experimental saltwater rehabilitation program. (Joe’s boyfriend at the time remembers only a broken shoulder and says the only saltwater rehab was snorkeling.)

Joe’s neighbor down there, a man named Tim, happened to be the manager of a pet store, and Tim’s friend worked at a drive-through zoo, one of those places where customers could ride around in safari cars and look out the windows at lions and other veld animals roaming (somewhat) free.

Joe remembers that Tim’s friend would sometimes bring home baby lions and let Joe play with them on their peach-colored carpet. In the drear of his life up to that point, these animals fluoresced. Imagine: to roll around on the living-room floor with a lion cub, something from so far away brought close enough to smell its warm, beasty fur. Joe liked to say he was broken and those little critters helped put him back together.

After a couple of years, Joe returned to Texas, got a job as a security guard at a gay cowboy bar called the Round-up Saloon, and met his first husband, Brian Rhyne, a slender, sassy 19-year-old. They moved into a trailer together in Arlington, where they shared their bed with a pack of poodles and grew to resemble each other, with mullets and horseshoe mustaches and dressed in jeans and boots. On Saturdays, they would snort pink-tinged meth and go out to the bars. Sundays, they lazed around at home and watched Westerns on TV. Joe and Brian eventually got married at the Round-up. This was the late ’80s. Gay marriage wasn’t even close to being legal, but they didn’t give a fuck.

Down the street from the trailer park where Joe and Brian lived was a pet store called Pet Safari. Joe got a job there, and later he and his brother Garold Wayne decided to purchase it. To attract a gay clientele, Joe hung rainbow banners outside and stocked the shelves with rainbow doggy T-shirts.

One day in October 1997, Joe received a call informing him that his brother had been involved in a car accident while driving to Florida. Garold died soon after. Joe’s parents won a sizable settlement from the trucking company responsible for the death, but his father refused to spend it, dismissing the settlement as “blood money.” Garold’s wife and kids wanted to build a soccer field in his honor, but Joe had another idea. It was his brother’s dream, Joe told them, to go to Africa and see wild lions and spend time with “people with bones in their noses and shit.” Since Garold never got to travel to the wilds of Africa, what if they could bring the wilds to people like Garold? So with the help of his parents, Joe purchased an old horse ranch in Wynnewood, Oklahoma, where he began building a refuge for rescued animals. He named it after his brother: the Garold Wayne Exotic Animal Memorial Park. Everyone called it the G.W. Zoo.

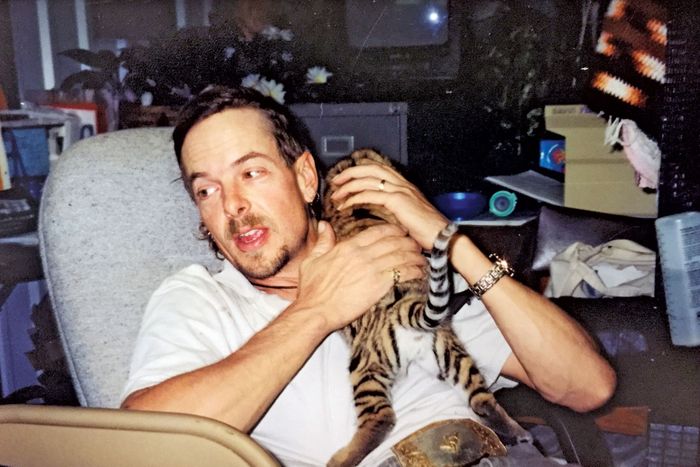

There was already a little ranch house on the property. Joe and Brian moved in. When new animals were born at the zoo, the babies lived in the house with him and Brian. As the years went by, Joe built more cages and fences all around the house, which he filled with lions and tigers and dogs until, almost without noticing, he became just another animal living inside a cage, inside the zoo.

Carole Stairs was a wild girl, fond of wild things. She took in stray cats, which she would take for walks through the swamplands around her house in Florida. She dreamed of being a veterinarian. But she dreaded the dullness of adulthood, of rules and routine. She recalls climbing a tree in her backyard, looking out over the expanse of ticky-tacky houses, and praying, God, I never want to be this bored again.

She ran away from home at the age of 15 in 1977 with an employee from the local roller rink. For a time, she hitchhiked up and down the coast, from Florida to Bangor, Maine. She learned that the safest place to sleep at night was underneath parked cars because no one thinks to look for you there. Later she got an orange Datsun truck and slept in the back with her pet cat.

She got a job at a discount department store back in Tampa, where her boss, Mike, offered to let her keep her cat at his apartment so it wouldn’t roast in the truck during the day. Carole was smitten; she moved in with Mike and then, at 17, married him and got pregnant with a daughter. Mike turned out to be monstrously possessive; he would mark her odometer each day to make sure she wasn’t sneaking around on him. So to make extra money, Carole began breeding Persian and Himalayan show cats from home, fluffy little freaks, their faces pressed so flat they could barely breathe. For fun, she began taking in injured bobcats, which she would rehabilitate and release. She preferred them to the house cats. They were just so unpredictable, so wicked.

One night, during a particularly bad argument, Carole could tell that Mike was going to beat her again, so she threw a potato at his head and ran out of the house barefoot. She ducked between houses to evade him. She was 19 years old, with blonde hair, big blue eyes, and a big smile; people were always confusing her with “that woman on TV.” While she was walking down the road, a car pulled up alongside her and rolled down the window. Inside was a tan older man with happy eyes who was dressed in shabby clothes. He asked if she needed a ride. Carole said, “No thanks,” and he drove off. A few minutes later, he pulled up again. This time, he had a revolver lying on the passenger seat. With a rakish smile, he told her that if she didn’t trust him, she could hold his gun on him. This is interesting, Carole thought. This is not boring.

Carole got in and picked up the gun. The man drove a little while, then pulled the car over. He reached over and wrapped his hands around her neck. He said he could choke her to death if he wanted. “I know,” she said coldly, without a trace of fear. He relaxed his hands and began to massage her shoulders.

He drove her to a cheap motel. She was nervous, but he assured her that he just wanted to spend the night in her company. Sure enough, they talked for a while and then went to sleep, with her wearing a baggy pair of his pajamas. He never pressed himself on her. “I fell in love with him then and there,” she later wrote in her diary.

The man told her his name was Bob Martin. Since they were both married, they had to have their clandestine meetings in a trailer at his work site; when Bob pulled into the lot, he would make her lie down on the floor of his truck so no one would see her. She thought they were hiding from his boss, a rich businessman named Don Lewis.

Whenever she called him at work, she would ask his secretary if she could speak with Bob Martin. One day, a different secretary answered the phone.

When Carole asked for Bob Martin, the secretary said she’d never heard of him. Carole described him — middle-aged, blond hair, blue eyes — and the secretary laughed. “You’re describing Don Lewis,” the secretary said. Carole realized she was having an affair with a millionaire.

Carole and Don eventually left their spouses and married each other in 1991. Soon after, they bought their first bobcat, Windsong, at an auction.

Windsong was a terror. She would lie on top of the refrigerator until Don opened it, then pounce on his head. She chased Carole’s daughter through the house and bullied their pet German shepherd. Don decided that she needed a playmate, so they drove up to meet a bobcat breeder in Minnesota. When they arrived, the flies were so thick that Carole had to put a handkerchief over her mouth to keep from inhaling them. The breeder had rows of cages filled with bobcat kittens, 56 of them in total.

Carole was confused.

“Is there really this big of a market for bobcats as pets?” she asked.

“Oh, no,” he said. “We’re a fur farm. We’ll just raise them until they’re a year old and then slaughter them.” In the corner of the room, Carole noticed a pile of dead cats with their belly fur sliced off. She burst into tears.

“How much for every cat here?” Don asked.

Every culture tells a different story about why it cages animals, which nearly all of them do. The stories evolve, and the cages do too. The rulers of ancient civilizations, including those of ancient Egypt and Babylon, kept vast menageries to display the extent of their empires. In ancient China, one imperial menagerie was called “the Garden of Intelligence,” where, Mencius reported, people “rejoiced” at the king’s possession of deer, fish, and turtles. During the European Enlightenment, many royal menageries were converted in the name of public education into “zoological parks,” where animals were arranged like living museum displays. In the 20th century, with the rise of the ecology and animal-rights movements, zoos were reframed as genetic arks for endangered species (plus some nonthreatened species like the plains zebra and hamadryas baboon, which are just fun to look at). Architects attempted to “naturalize” these environments and, not coincidentally, to help us forget about the increasingly troubling reality of animal captivity. Steel bars were replaced with “open” enclosures separated from the public by moats or thick glass.

Visitors who were accustomed to these big-city zoos were sometimes shocked, upon entering the G.W. Zoo in Wynnewood, Oklahoma, to find row upon row of steel cages. But the naked-steel cages at the G.W. Zoo struck other visitors as refreshingly honest. After all, enclosure is a zoo’s essential quality: Children will run screaming in terror from a bee aloft, but put it under glass and they will gather round, transfixed. Joe just made the ugly truth visible.

And as he would point out, unlike glass, steel cages are porous. People can smell the animals, hear them breathe and chuff and roar. Visitors to the G.W. Zoo often got sprayed with lion urine and “bombed” with ape feces.

Afterward, they proudly bought T-shirts in the gift shop that read I GOT PEED ON BY A LION. It seemed to scratch some deep itch they had for close contact with wild animals — a kind of therapeutic disalienation from nature — which big zoos (and, indeed, the actual wilderness) so often fail to satisfy.

Today there are hundreds of roadside zoos like Joe’s in America — probably more than there are accredited ones. But the term “roadside zoo” is considered something of a slur in the exotic-animal world. Joe despised it. Big zoos have an ethical mission (conservation and education), and sanctuaries have one as well (caring for unwanted animals). But roadside zoos, as the name implies, have none. They are motivated purely by profit, like freak shows.

Joe made it very clear that his “park” was a sanctuary, not a zoo. (“I keep all the retards,” was how he liked to put it.) Over the years, he had discovered that a shocking number of exotic animals were living in backyards and basements all across the country, many of which had grown too large or too dangerous for their owners. The laws on big-cat ownership were, and remain, lax. All that is needed to buy a tiger cub is a USDA exhibitor’s license, which costs $40. According to some estimates, more tigers are being kept in captivity in America than are living in the wild in the entire rest of the world.

Once word got around that Joe was willing to rescue adult big cats — which most people wouldn’t because they are dangerous to handle and expensive to feed — more and more of them began pouring in. Within two years, Joe had already amassed more than a dozen. He persuaded the local Walmart to donate its expired meat, which he would feed to the cats. He also secured donations from sponsors. But it was never enough. Joe borrowed more and more money from his parents to cover the bills. Eventually, he had a profound (and profitable) realization: When faced with a caged tiger, some people keep their distance. Others instinctively lean closer. Why not let those people inside the cage?

By the mid-1990s, Carole and Don had acquired more than 100 cats. They kept them on a 40-acre piece of land that lay at the end of a dirt road called Easy Street, so they began calling their collection — not quite a zoo and not quite a sanctuary — Wildlife on Easy Street. When word got around that they were taking in unwanted cats, they began receiving calls from people asking to take their lions and tigers as well as smaller cats like servals and caracals. They built cages inside and outside the house, including one around Carole’s desk so the cats wouldn’t pee on her fax machine. They also opened a small bed-and-breakfast, where guests could spend the night with bobcats and cougars. Guests would emerge sleep-deprived and frazzled but radiant with the experience of seeing wildness up close.

Don and Carole began to clash over how the facility should be run. Don enjoyed breeding cats and selling cats and making money. But Carole came to believe the breeding of big cats was a gross moral injustice. Breeding more wildcats simply meant more wildcats that would spend their lives in cages. The thought of it sometimes brought her to tears.

Don could be a cruel man. The word Carole used in her diary was venomous. Their fiercest fights were about money. Don — who had clawed his way up from a hardscrabble childhood to build a successful business selling and scrapping metal and machine parts, then buying distressed real-estate assets — was notoriously stingy. (He could often be found dumpster diving behind the local grocery for day-old bread.) He bought Carole a cubic-zirconia wedding ring and refused to pay her daughter’s cable bill. He was also notoriously promiscuous, and Carole knew it.

In June 1997, their fighting escalated, and Don filed a petition for a restraining order against Carole. He told police she had threatened to shoot him if he didn’t leave the house. The petition was rejected, but he gave a copy to his secretary, Anne McQueen, telling her to keep it somewhere safe in case anything ever happened to him.

A few weeks later, Don abruptly disappeared. Carole says he got up before her that morning and said he was going to Miami. He was never seen again. His van was found at a nearby airport, but employees there reported never having seen him, and there was no evidence of his taking off in a plane that day. For a time, Don was believed to have absconded to Costa Rica, but detectives sent there to find him came up with nothing. Don’s daughter publicly accused Carole of killing him, grinding up his body, and feeding it to her tigers. These claims were never substantiated, and police say Carole was never named as a suspect.

After Don’s disappearance, Carole and Don’s kids became embroiled in a fierce battle over his sizable estate. But the land on Easy Street, and all the cats, now belonged solely to Carole. She tore down the last rows of dog-kennel-style cages and constructed larger enclosures built around shady live oaks, so every cat’s feet could touch the earth.

For Joe, there was never enough money; the cats just ate it up. To make more, he began traveling to local flea markets with a full-grown tiger named Clint Black. For $5, people could pose for a Polaroid with him. Then, when that became too dangerous, he switched to using baby tigers, which were cuter anyway. (The USDA recommends that only cubs between four and 12 weeks are safe to handle.) He began taking his petting zoo to shopping malls and flea markets in ever-widening orbits.

In 2002, Joe met a talented magician named Johnny Magic, and they briefly combined their efforts — Joe bringing animals onstage and Johnny performing illusions. In one of their most popular tricks, a baby tiger was magically transformed into a full-grown one. When Johnny Magic decided to leave Joe, Joe stole many of the tricks and folded the cub-petting into a magic show, which he called Mystical Magic of the Endangered. At first, he toured in a 1969 Frito-Lay truck. As the scale of his operation grew, he upgraded to a Winnebago, then a proper tour bus. And he gave himself a new name. That’s when Joe Schreibvogel finally became Joe Exotic.

The magic show let Joe spend time onstage bathing in applause, which he enjoyed, but it was primarily meant to draw people to the petting zoo, where the bulk of the money was made. People were willing to pay $25 to hold a baby tiger for six minutes and $25 more for a glossy photo; Joe bragged that his mobile petting zoo once pulled in $23,697 in five days. It also created a new dilemma: In order to have a steady supply of baby tigers, Joe needed to be constantly breeding them. But once they grew up, they were expensive to keep alive, which required more money, which required more cubs. He was caught in a vicious circle.

In 2002, while at a cocktail party at a local aquarium, Carole met Howard Baskin. A tall, slender, beaky management consultant 11 years her senior who had an M.B.A. from Harvard as well as a law degree, he was the opposite of the dangerous, charismatic men she tended to date.

Howard and Carole married two years later in a ceremony on the beach.

Carole wore a white dress and a wreath of flowers in her hair. At the last minute, Howard surprised her by showing up in a novelty caveman costume. She found it hilarious. After the ceremony, they took goofy photos: In one, he’s clubbing her over the head. In another, she has hooked a leash onto a collar around his neck and he kneels obediently by her side.

On their honeymoon in the Virgin Islands, Carole — who was an avid believer in the cosmic-wish-fulfillment doctrine known as the Secret — began typing out her dream: a 20-year plan to end the captive ownership of big cats in America. By 2025, she aimed to end the breeding, sale, and public display of big cats, including in zoos. With no more big cats being bred, sanctuaries too would eventually close as their stock died off. At last — ever since a merchant named Arthur Savage first charged onlookers to see an African lion in his Boston home in 1716 — there would no longer be tigers or lions in America.

But first, she needed to stop people from breeding them.

When he first opened the animal park, Joe was vociferously opposed to breeding tigers. He frequently lectured his guests that while tiger cubs may be cute when they’re young, they grow up quick and they grow up mean. But when he started charging people money to pet his cubs, his views evolved along with his business model. He became skilled at breeding cubs and keeping them alive; his secret was that he used horse vitamins, rather than pet vitamins, a trick he’d learned from his father. He also took in horses that people donated to him, shot them in the head, and gave them to the tigers, hair and all, so they could be fed a diet resembling what they’d eat in the wild.

Eventually, Joe would become, by his own estimation, the largest breeder of tigers in the country — a claim of which he was proud. He came to see himself as preserving the species. Captivity, he liked to say, is the only hope. The wilderness keeps shrinking, and poachers keep poaching. So if you’re not for breeding, you’re for extinction.

One day in 2003, Joe traveled to another zoo in Oklahoma and saw his first liger — the offspring of a tiger and a lion. Ligers do not exist anywhere in the wild, but they can be bred in captivity. Due to a quirk in their combined genetics, they can grow to be much larger than either tigers or lions.

Joe was impressed. When he got back to the park, he put a pair of tigers with lions, and soon his first liger was born. Then he decided to house the liger with a lion, and a year later the first liliger was born — half-lion, half-liger. Joe would go on to create a tiliger and even a tililiger (or T3) — creatures that existed almost nowhere else on earth. Some of these hybrids grew to monstrous size; Joe’s largest weighed over a thousand pounds. By continuing on this trajectory, Joe believed he could re-create a prehistoric sabertooth tiger. (Big-cat biologists universally agree that this is absurd.)

By this point, Joe Exotic had begun to mutate into a new body more befitting his name. His mullet was dyed blond. He dressed in spangly shirts and leather chaps. On his left hand grew a long, carefully manicured pinkie nail. He was covered in tattoos: one of a monkey named Ricky, one of a tiger named Sarge, one of a peacock, deer antlers, tiger stripes, and later (as his persecution by animals-rights activists mounted) three fake bullet holes in his chest, forever dripping, like modern-day stigmata. Permanent eyeliner was tattooed around his eyes. Over the years, he got so many face-lifts, one employee said, that he made her pluck his sideburns, which now grew behind his ears. His ears were pierced, as was his eyebrow. He even got his penis pierced; he claimed his barbell was the size of a Master padlock.

Employees at the zoo from that time liken the change to a snowball being pushed down a hill. It had begun, many of them say, when Brian Rhyne, Joe’s first husband, died of complications related to HIV in 2001. Joe was loading him into a pickup to take him home to die peacefully, when he breathed his last breath. Joe screamed loud enough to make your ears ring.

Afterward, Joe’s taste in men seemed to change. He began spending more time at a gay bar called the Copa, which stands just off Route 66. Joe was notorious for having once walked in, on a busy Saturday night, with a tiger on a leash. The men he gravitated toward were very young and very rough, and they often professed to be heterosexual. It was a volatile combination. Joe’s next husband, a 20-something from Oklahoma named J. C. Hartpence, once held a gun to Joe’s head in a drunken rage. (He is now serving life in prison for a murder he committed years after he and Joe split up.) Joe’s husband after J.C., John Finlay, who started dating Joe mere months after graduating from high school, was a cute little redneck boy who hid his teeth when he smiled; he later grew long rattail-style hair, began taking steroids at Joe’s behest, and became prone to attacks of rage. On one occasion, he threw Joe into a wall hard enough to send him to the hospital.

While dating John, Joe seduced a young man named Paul (who asked me not to reveal his last name). Paul was quiet, withdrawn, a fan of Insane Clown Posse. He (like John and J.C.) doesn’t identify as gay. Joe, John, and Paul all slept in one bed, with Joe in the middle. When Paul left, Joe found a new husband, named Travis, a dark-haired skater kid from California with mischievous eyes, who also told everyone (except Joe) that he was straight. Joe eventually married Travis and John simultaneously. (John later left Joe for a woman, with whom he had a child.) These young men mostly came from rough circumstances, and Joe believed he was giving them a good home. He paid for John to get a tattoo, just above his pelvis, that read PRIVATELY OWNED BY JOE EXOTIC.

With Howard’s help, Carole reinvented Wildlife on Easy Street. They renamed it Big Cat Rescue. But rather than rescuing more cats, which is a hydra-headed struggle — the more cats you rescue, the more people breed, secure in the knowledge that they can simply off-load them once they become dangerous — they focused on fund-raising (Howard’s forte) and building their online following. Carole proved to be a wizard at the latter. She taught herself to code, built a website, and started creating pages calling out the people who were (in her eyes) the worst abusers. She also took to social media like a natural. She mostly posted cute videos of her big cats, but when the cause was righteous, her tone grew razor-sharp.

One key to stopping the rampant breeding of big cats, Carole realized, was to stop the cub-petting industry, which she estimated was responsible for 90 percent of tigers and lions born in America. She began contacting shopping malls that were hosting cub-petting zoos to voice her outrage. She marshaled her followers to do the same.

One day in 2009, as she was scrolling through photos of various cub-petting operations, she began noticing the same face at multiple malls, operating under different names. It was a scrawny man with a blond mullet and black eyeliner. He was a magician. Sometimes he went by the name Aarron Alex, sometimes by Cody Ryan. Most often, he went by Joe Exotic.

Carole began emailing malls, and she hired a part-time staff member to do the same. She threatened to expose these malls on Big Cat Rescue’s YouTube channel, which she said was the second-most-viewed nonprofit channel in the world. They tracked Joe’s whereabouts; at one point, she even hired someone to follow his road crew around full time. She used a program called Capwiz— the same one used by organizations to email-blast congresspeople — to get her tens of thousands of online followers to flood malls with complaints. Occasionally, mall managers would call her office to say their system had crashed. “We’ll never have cubs again,” they begged. “Stop. Just stop.” A handful of malls agreed not to host Joe, then ten, then a hundred.

Joe felt hunted. Over the years, animal-rights groups like PETA and the Humane Society had begun sending spies to film his road shows and even to infiltrate his staff at the zoo, but Joe was always able to shake them off.

This Carole lady, on the other hand, was just relentless. She had more online supporters, more money, and — infuriatingly — the moral high ground. But was she really any better than he was? She had cats in cages, just like him. She charged money for tours, just like him. The difference, Joe believed, was that she had found a rich husband who’d died mysteriously, whereas Joe had to scrape for every penny he had (minus the trust fund he received from his wealthy grandfather, which totaled about $250,000).

In September 2010, Joe made a covert visit to Big Cat Rescue. He even paid to survey the property from a helicopter; he hung out the open door and took photos while John held him by the belt. On that trip, he received a cache of documents, including Carole’s diary, which had been stolen from her computer by a former employee. Joe posted many of these online, purporting that they suggested Carole had killed her late husband Don. “Carole will go to jail, if it is the last thing I see in my life,” Joe wrote online. He began offering a $10,000 reward for any information leading to Carole’s arrest.

Back at the zoo, Joe started making YouTube videos himself, using a Hi8 camcorder, to attack Carole. He called them “the Sagas.” He signed off every video with the tagline “Carole, I ain’t got nothing better to do than fuck with you.” He also created a slew of new websites to attack her and her allies. One site was called animalsluts.org; apparently, the site was often confused with the porn site animalsluts.com because the header read, “Incase [sic] your [sic] stupid or just plain ignorant this site is not about Bestiality … ” According to those who knew him, Joe had two goals by this point in his life, which burned in him with all-consuming — ultimately self-immolating — intensity: He wanted to become famous, and he wanted to destroy Carole and her allies in the animal-rights world. The two meshed neatly: The bigger the platform he had, the more effectively he could squash Carole. And the louder he raged against Carole, the more famous he became. “I’d like to thank you for all of the publicity you’ve been giving me recently,” Joe said to Carole in one of these videos. “Because I am making tons of money. Drama makes money, Carole. You know that better than anybody in the world.”

His war extended beyond the internet. One day, he decided that if Carole was going to attack him for doing cub petting, then he would simply change the name of his company to the name of her company. That way, her fans would come to believe that she was a hypocrite. He instructed his employee Aaron Stone — a magician who had joined him on his road show and one of the few computer-savvy members of his staff — to replicate her logo. They printed it on business cards and fliers, along with a Florida phone number that Joe registered. And then they began touring, as Big Cat Rescue Entertainment.

The plan worked — at first. Carole and Howard began receiving confused, outraged, and sometimes tearful phone calls and emails asking why they were participating in cub petting. In February 2011, Carole filed a lawsuit against Joe for trademark infringement, asking for roughly $1 million in punitive damages. (Joe countersued, but his suit was thrown out.) The proceedings dragged on for years. Eventually, Joe, wearied by the mounting legal fees, consented to a judgment. “She just out-moneyed me” was how he put it. The judge awarded the Baskins just over $1 million. Joe promptly filed for bankruptcy, transferred the land to his mom, and changed the name of the zoo, giving himself the new title “entertainment director.”

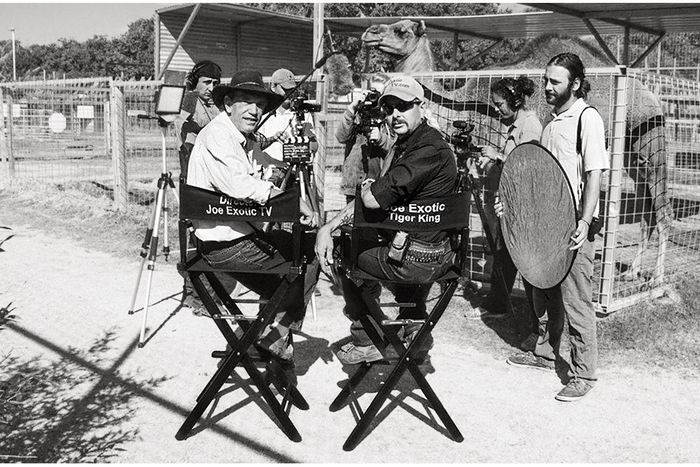

The silver lining was that the media attention resulting from the lawsuit had made Joe into a minor celebrity. He had been contacted by a company called Good Clean Fun productions, which produced The Bachelor, to make a reality show in the mold of Duck Dynasty. That deal never panned out, so Joe decided to make the show himself. He invested in a green screen, new cameras, and a movie-premiere-style backdrop with JOE EXOTIC TV printed all over it, which he would use while holding press conferences about himself. He cut a sizzle reel. He hired a crew. Soon he was spending tens of thousands of dollars a year producing a live nightly chat show, complete with prerecorded segments from the zoo, that was viewed by a few dozen people each night. (Joe insists these segments were moneymakers.) He also broadcast himself singing country music, mostly treacly ballads about his love of big cats and wild men. (It was later revealed that Joe was merely lip-syncing the songs. They were written and performed by a duo in Washington State.)

In 2014, Joe hired a new producer, Rick Kirkham, to help with the reality show. Kirkham pushed for greater theatricality. He urged Joe, who had dubbed himself “the Tiger King,” to build a throne so they could film him sitting on it, wearing a crown, for a sizzle reel. Late one night, Rick walked in on Joe, who was sitting in the dark, eyes aglow, watching that 12-second clip over and over. “Just look at me,” Joe said. “The Tiger King … ”

The zoo increasingly took on the queasy, paranoiac quality of a walled kingdom run by a mad king. At night, according to his staff, Joe locked the gates, which meant the employees couldn’t leave. The workers couldn’t always afford food on their pay — they made between $150 and $300 a week, far below the minimum wage — so they resorted to eating the expired steaks and hot dogs that Walmart had donated to the cats. (When he later opened a restaurant, Joe would be caught feeding this meat to customers.)

Joe advertised on Craigslist, and many of his new employees were either fresh out of jail or fresh out of rehab. There were frequent outbreaks of scabies and ringworm among the staff, which would spread from one trailer to the next and back again. Employees were also caught (and filmed) acting as spies for animal-rights organizations. Joe believed his computers had been hacked by Carole Baskin. (Hacking had in fact occurred, but it was committed by a cannabis-themed YouTuber named George Jones, who went by “Nat Geo.”) Joe instructed his staff, “Don’t trust anyone. Even in your crew, be suspicious.”

Drugs worsened matters. Joe immediately fired anyone who was caught getting high, but multiple employees say Joe himself was frequently taking drugs, especially meth. One employee recalls Joe, jittery and wild-eyed, giving a lecture to a group of schoolchildren about the dangers of drugs and alcohol, while sniffing and wiping at his nose.

Not surprisingly, accidents were frequent. Joe was bitten and scratched many times; on one occasion, he says, while he was trying to walk a tiger on a leash, it bit down on his leg so hard it broke off a tooth. The tiger’s name was Chainsaw, so whenever people asked about Joe’s leg, he just told them he’d had a “chain-saw accident.”

The worst incident occurred in October 2013. An employee named Saff was moving a tiger from its main cage to a smaller one called a shift pen. Rather than using a bull hook to close the door, as he normally would, he impulsively reached his arm into the tiger cage. Within seconds, the tiger had bitten down on his hand, breaking his middle finger. Saff looked up at the employee next to him and said, “This is going to be bad.”

The tiger flexed its claws and began raking them down his arm. Saff was wearing a down jacket that day, so for a few moments the claws tore through nothing more than fabric. White feathers floated innocently in the cold air.

Then the claws reached skin — and what lies beneath.

Joe’s video crew captured the aftermath of the accident — Saff lying on the ground beside the cage in shock, his arm flayed to red shreds, the bone bright white, as if boiled. Saff ultimately lost his arm. But amazingly, he returned to work at the zoo soon after. He repeatedly, and publicly, apologized to Joe for any harm this accident may have caused Joe’s, or the zoo’s, reputation.

In March of 2015, a mysterious fire burned down Joe’s TV studio and an adjoining enclosure, killing a number of baby alligators that were the offspring of an alligator that had lived at Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch. Joe claimed that Carole had paid Rick $20,000 to start it. Rick claimed that Joe had paid one of his employees to start it to destroy (or pretend to destroy) incriminating footage. The case has never been solved. Immediately after the fire, Rick moved to Texas; in a strange coincidence six months later, his house burned down in the middle of the night, killing his dog and almost killing him.

Around this time, Joe’s never-ending supply of Insta-friendly baby tigers had begun attracting a number of high-profile fans. The porn actress Rachel Starr and the former pro basketball player Shaquille O’Neal were frequent visitors. (Upon seeing Shaq for the first time, Joe failed to recognize him. According to Joe, he turned to one of his employees and said, “Goddamn, did you see that big [N-word]?”)

One night, Joe took a rapper named Radio Raheem and his entourage out to dinner at a Mexican restaurant in Paul’s Valley. Hunched over his plate of fajitas and a big red plastic cup of Coke, Joe looked both haggard and wired, like a movie hooker. He claimed to be dying from prostate and bone-marrow cancer. (He wasn’t.) Joe announced to the table that in preparation for the “special occasion” when his doctor would say he had two months left to live, he had purchased an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle and two hundred-round clips. On that day, Joe said, he would finally go hunt down his nemesis, Carole Baskin.

Everyone at the table laughed in an overloud, nervous way.

“I used to never fantasize about somebody’s brains on a wall,” Joe said.

Laughter, but softer.

Joe went on to describe how he would mutilate her dead body. “There’s going to be tree branches in every orifice, dude,” he said. By now, no one was laughing except Joe and one glossy-haired woman seated to his left, who seemed near hysterical with the awkwardness of the situation. “Seriously, after everything she’s put me through, going to jail is nothing to me. I’m going to die in a couple of years. What the hell?”

“Joe, you’re getting a little crazy,” Radio Raheem said.

“She has drove me to that point,” Joe replied.

That same month, Carole received a call from a woman named Jacqueline Thompson, who informed her that she had overheard some people talking about a plot to kill Carole; they had discussed injecting Carole with ketamine, throwing her in the back of a truck, and dumping her body in a swamp. On another occasion, Carole received a voice-mail from a young woman named Ashley Paige Webster, who said Joe had offered her a few thousand dollars to kill her. “I feel like your life is in danger,” she said.

Carole contacted law-enforcement officials repeatedly and forwarded them these warnings along with the scores of thinly veiled threats Joe had made online, but she was told that until Joe physically attacked her, there was nothing they could do — the threats may be real, or they may be mere provocation. With a guy like Joe, a post-truth creature of the internet, it was sometimes too difficult to tell the difference.

Meanwhile, the Baskins, certain they would never collect the million dollars owed to them, began a court-ordered mediation with Joe. They offered to relieve some of Joe’s debt, provided he formally agreed to stop cub petting and breeding. And they came close to achieving an agreement. But then, in late 2015, in the middle of a phone call between Joe, Howard, their lawyers, and a mediator, a voice butted in that Howard had never heard before.

“We’re not doing this deal,” the voice said.

“Who’s speaking, please?” the mediator asked.

“Jeff Lowe,” the man said.

The mediator ordered Jeff Lowe, whoever he was, to get off the call.

“All I want to say,” Jeff Lowe said, “is fuck Howard and his cunt wife.”

Jeff Lowe had eyes the color of snowmelt and a neatly trimmed gray goatee. He wore leather jackets, fancy jeans, and a black do-rag wrapped around his balding head. He once worked as Robbie Knievel’s manager and now ran a liquidation business. He drove a red Ferrari and a white Hummer. He was once arrested for assaulting his wife. Another time, he was arrested for, and later pleaded guilty to, falsely posing as an employee of Citizens Opposed to Domestic Abuse so he could receive donated goods, which he then resold.

Lowe owned 12 big cats, which he kept in a warehouse in his hometown of Beaufort. He had tried to open a cub-petting operation in a flea market but was shut down by county officials. He believed Carole had been a catalyst behind the protests against him. He referred to her as “the devil incarnate.”

Joe and Jeff had made an agreement: Joe would effectively sign ownership of the zoo over to Jeff, and Jeff would help pay to fight Carole. To raise more funds, Jeff moved to Vegas. He began sneaking tiger cubs, hidden inside a Louis Vuitton dog carrier, into hotel rooms along the Strip and charging high rollers $2,000 to pet them.

Meanwhile, back at the zoo, Joe was going through yet another, Pokémonic evolution. Inspired by the unlikely ascension of Donald Trump, Joe launched his own campaign for the presidency in 2015 and then for governor in 2018; he was planning to run for president again, this time on the Libertarian ticket. (This despite the fact that Joe was not a libertarian, nor did he even seem to know what the word meant. He was more of an idiosyncratic populist; one of his campaign pledges was to bring back spanking in schools. Josh Dial, who ran Joe’s campaign, likened him to “Donald Trump on meth.”) Joe printed his name on the side of a stretch limo and on hundreds of yard signs. His staff was baffled by the amount of money he was wasting on these doomed campaigns, but Joe insisted they were not merely vanity projects. He often asked, rhetorically, “How do a normal person like me ever get heard in this country?”

One dark day in October 2017, Travis Maldonado, Joe’s 23-year-old husband, accidentally shot himself in the head with a pistol and died. In the following weeks, Joe became untethered. He began having visions. First, he sensed Travis’s presence in a honeybee that landed on his finger when he was about to fire his AR-15. Then he sensed Travis’s spirit in a blue-heeler dog. He spent a lot of time staring at the clouds.

One night soon after, Joe was sitting alone in his house, crying. He lifted his .357 Magnum revolver and shot the television, shot the couch, and then put the gun to his head and pulled the trigger. The hammer hit the bullet and dented in the primer but did not go off. Afterward, Joe made a necklace out of it as a memento mori.

He also set out to find a new husband. He assigned members of his office staff to locate new prospects, using Grindr and Twitter, and soon he met a lithe, smiley young man named Dillon Passage, who was sleeping on an air mattress at his cousin’s house. Within days, Joe had him living in his home.

They were married on December 11, two months after Travis’s death.

Joe began telling certain people that he wanted out of the zoo business.

He even donated a number of animals — 20 tigers, three bears, two baboons, and two chimpanzees — to PETA, an organization he used to despise. He also killed five tigers — named Samson, Delilah, Trinity, Lauren, and Cuddles — with a shotgun blast to the skull. Joe would later claim they had “toenails coming out of their ankles” and “exposed root canals,” but other employees present that day believe they were healthy. After shooting all five, Joe reportedly turned to one employee and said, perhaps in jest, “Jesus. If I knew it was this easy, I’d just blast them all.”

By this point, a new employee named Alan Glover was at the zoo. Alan was a hulk of a man with a shaved head, a sailor’s deeply reddened face, and a voice as low and grumbly as a motorcycle engine. He had a teardrop tattoo under his left eye. He had previously worked for Jeff Lowe back in South Carolina. Lowe persuaded him to move to Oklahoma to help out with basic maintenance and yard work. He had arrived carrying nothing but a small suitcase and a chain saw.

One night after work, Joe made Alan an offer: He would pay him to kill Carole Baskin. Joe promised him $5,000 up front and $10,000 (or more) on the back end if he pulled it off. Joe suggested he find the bike path Carole often took to get to work, wait for her wearing a camouflage “ghillie suit” — the shaggy, leafy kind snipers wear — and shoot her using a crossbow or rifle. Alan told Joe he couldn’t carry a gun because he was a convicted felon. (Beginning in 1985, he spent five years in prison for aggravated assault and battery.) Instead, Alan suggested he travel to Tampa, buy a knife, and cut Carole’s head off. Joe said he was fine with that.

On November 8, one of Joe’s friends, a former strip-club proprietor and fellow tiger owner named James Garretson, came to the zoo and struck up a conversation with Alan. Alan asked James to procure him a prostitute. James assured him he could make that happen. (In his phone, Alan had James listed simply as “Pussy.”) Then James asked Alan about the upcoming hit.

“How long you gonna be vacationing down in Florida?” James asked

“As long as it takes,” Alan said.

“Make sure he pays you real good.”

“He is gonna be in my pocket forever. You know that …”

“That Baskin definitely is fucking, trying to fuck everybody.”

Alan sighed. “I’m going to hell anyway.”

“I think we’re all going.”

“I’m going straight there,” Alan said. “I have no chance.”

Alan said that once he went to Tampa, no one would hear from him until news of Carole’s murder was on television. He added, “And if anybody rats me out and I get popped, everybody that they love, I’ll have them burnt alive. Every fucking single person. And I mean that from the bottom of my heart. They will be burnt the fuck alive.”

Unbeknownst to Joe or Alan, James Garretson was secretly recording their conversations for the FBI. Over the course of many months, what had begun as a Fish and Wildlife Service investigation into Joe’s animal crimes had evolved into a murder-for-hire case.

After he left, Alan went dark. Neither Joe nor the federal agents knew where he’d disappeared to. When Joe finally did hear back, he learned that, instead of going to Florida, Alan had simply taken Joe’s money and traveled home to South Carolina, where he spent much of his time getting drunk.

When it became clear to the FBI that the plot with Alan had fallen through, the agents working on the case decided to introduce Joe to an undercover agent posing as a second hit man, nicknamed “Mark.” On December 8, Joe welcomed Mark into his office and they spoke for 45 minutes while a skunk prowled beneath the desks.

Talk turned to Carole.

“This bitch has cost us almost three-quarter of a million dollars in lawyers already,” Joe complained. Joe showed Mark his file folder bulging with information he had collected about Carole, including her personal diary. “She’s a sick bitch,” Joe said, chuckling. He suggested that he could buy Mark a pistol at a flea market. Mark could drive up to Carole in a parking lot, “cap her,” and drive off, he said. Mark asked for $10,000 — half up front. Joe said he could scrounge up the money. “I’ll just sell a bunch of tigers,” he said.

In the spring, Jeff Lowe and his girlfriend, Lauren Dropla, a slender young redhead with pale skin and the face of a da Vinci portrait, moved back to the zoo. Jeff had just been arrested in Las Vegas for illegally possessing exotic animals and firearms and had decided to get out of Dodge. He and Lauren moved into a wooden cabin on the property, a stark change from the spacious McMansions he normally lived in. From the moment he returned, things were tense. The zoo was strapped for cash, and both Jeff and Joe were now tangled up in lawsuits with Carole.

The final thread snapped on June 15. Joe was attempting to euthanize ten tigers when Lowe intervened and ordered him to get off the property. Joe thought, The hell with it, and left that day, then posted a farewell video on Facebook Live from the back of his stretch limo. His voice croaky, his eyes welling with tears, he said, “The animal industry has sucked the life out of me for the past 20 years. I need a break. That’s about all I have to say.”

He and Dillon drifted for a time. Joe was convinced he was being followed, so he started posting cryptic messages on his Instagram account to obscure his whereabouts. In one, he took a shot of the ocean and wrote, “Omg California is so amazing.” In another, he posted a photo of Dillon shirtless on the beach. “So he wants to call this home?,” he wrote. “Ok. I give in #belize #Mexico #gay #gayboy #carabianbeach.”

In reality, they had moved to Gulf Breeze, Florida. Joe and Dillon lived a mile and a half from the beach; in their free time, they played Frisbee with their dogs, went swimming in the Gulf, and watched Orange Is the New Black on Netflix. Joe was nowhere near Carole; Tampa was a seven-hour drive south. He just wanted to start over.

One dewy morning in September, Joe was walking into a hospital to inquire about any job openings when four unmarked cars surrounded him. Joe told a reporter he was thrown on the ground and an officer knelt on his back so hard you could hear his ribs popping. The officer in charge denies this; he says Joe laid down all by himself and “made no complaints of pain or discomfort.” Joe was booked and sent to jail.

Unbeknownst to Joe, the FBI had finally tracked down Alan Glover, who had told them all about the plot thanks in large part to the cooperation of Jeff Lowe.

In March, Joe stood trial for two counts of murder for hire and 17 counts of exotic-animal abuse, including the killing of five tigers.

Wearing an ill-fitting suit, his mullet neatly combed, Joe looked restless throughout the trial, rocking back and forth in his chair and twitching his nose; he often leaned over and whispered comments or suggestions into the ears of his attorneys, who stoically ignored him.

At the end of the trial, Joe took the stand to testify in his own defense. Much of his testimony was given over to disparaging Carole and Big Cat Rescue. “My problem is she’s a hypocrite,” he said. He said her sanctuary was no better than a roadside zoo. His eyes looked happy. This was his last stand, the moment when Carole would be exposed to all the world. But as his rant went on and on, the jurors looked skeptical, then sleepy, and the journalists’ pens slowed to a stop.

At one point in the middle of Joe’s testimony, his attorney asked Joe a question about Travis’s death, and Joe abruptly — instantaneously — broke down in tears. He began wiping his cheeks with the palms of his hands in an exaggerated, childlike manner. “I just didn’t buy it,” one juror later said. “I think it was how fast the tears came on. They just started pouring out of nowhere … And maybe it was just because his character was in question the whole time that I just had a hard time feeling sorry for him.”

The jury deliberated for only three hours, then found Joe guilty on all counts. He is still awaiting sentencing.

From inside jail, Joe has publicly declared that he has two missions in life from this point forward. The first is pushing for penal reform. (“My main bitch right now,” he said, “is there is more regulations under the Animal Welfare Act to take care of an animal at a zoo than there is for taking human beings in jail.”) The second is pioneering a new kind of zoo — one without cages. He daydreams about tigers and lions running free across vast fenced-in tracts of land, lounging under trees, chasing deer and antelope. He feels remorse for all those years he kept tigers in small cages. He now understands exactly how they felt. “Sitting there all day with fucking nothing to do,” he said. “Looking through bars.”

On this, Joe and Carole finally agree. “I think it is poetic justice,” she said, “that he could potentially spend the rest of his life in a cage.” She is currently lobbying to pass legislation to further tighten regulations on big-cat ownership in America. In the meantime, she’s working to take down other animal exploiters; she knows she will be in their crosshairs as well. “I’m happy that Joe is behind bars,” she said, “but of all of the people who exploit these animals, I feel like he’s just the dumbest of the lot. There are plenty of people that are a whole lot smarter than him and better funded and a lot sneakier that would be much more capable of pulling off my murder than Joe was.” She is not cowed. The footer to her emails is a quote by FDR: “Judge me by the enemies I have made.”

Carole recently launched a new project — a virtual zoo, where people can don electronic headsets and see the view from inside the cats’ enclosures with startling clarity. For the first time in human history, people will finally be able to experience the brutal, slinky grandeur of tigers and lions up close without forcing them to live in cages. She already has a prototype set up in a former retail space in the shopping mall across the street. The future, she calls it.

This story was reported in partnership with Over My Dead Body Season 2: Joe Exotic, by Wondery. You can find the podcast here.

*This article appears in the September 2, 2019, issue of New YorkMagazine. Subscribe Now!