Last Tuesday, Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene hosted a talk with the author Kate Elizabeth Russell. Few signs of anything amiss could be discerned. The event was so well attended that dozens of audience members had to stand in the aisles, and no one seemed particularly concerned about the possibility that deadly germs were lingering on their plastic cups of wine.

By Thursday, Greenlight had decided to cancel all events, but its doors remained open, and customers continued to file into the store, stocking up on books and puzzles to occupy their minds during the lonely days to come. Stories of pandemics were selling well — Ling Ma’s Severance, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven — as were the sorts of thick, ambitious tomes that are more often spoken of than read.

And then came Monday, when the city and state tightened restrictions on bars and restaurants and students stopped going to school. Greenlight sent out an email to its customers noting that “the moment has come to do more.” Along with most of the city’s other indie bookstores, it was shutting its doors to the public.

The sense of doom and gloom that has suddenly descended over the world is, in some ways, not altogether unfamiliar to people in the publishing business. For the last decade, as the internet has encroached on the mental space we once reserved for reading, people who rely on books for a living have wondered how long their jobs will last. But amid the shuttering of chains like Borders, the rise of the indie bookstore has been a bright spot. These stores have thrived and multiplied because they provide what Amazon can’t: conversations with authors, story hours for kids, cozy spaces where readers can gather, staff members eager to recommend something to fill the void once you’ve torn through all of Tana French’s mysteries. In an increasingly atomized, online world, they offer a sense of community that augments the value of the books themselves, and that was never clearer than in the days before they closed.

On Friday, at Books Are Magic in Cobble Hill, the co-owner and author Emma Straub sat on a leather couch wearing a hand-drawn pin reminding customers to wash their hands. Nearby, kids and their parents slouched in beanbag chairs, flipping through picture books about dragons and princesses and snow days. The cozy scene stood in stark contrast to the fear and uncertainty of the world outside the store. “This is the whole point,” said Straub, looking at the families wistfully. By then, she had made the difficult decision to cancel all events. Just two nights earlier, Maira Kalman had given a talk about her new illustrated edition of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. “She was so perfect and so funny and warm and talked about art and family and New York City, and it made me feel so happy,” Straub said, as though reminiscing about something that happened years ago. In another two days, Books Are Magic would close, but Straub was still oblivious about what was to come. “We’re gonna be here, even if the rest of our staff is staying home,” Straub said. “I’m gonna need a crowbar to get my husband out of here.” As with the rest of the world, the realization that life as we know it was ending came in waves, with each day wiping out the previous day’s understanding of the crisis.

Mil Mundos, a bilingual bookstore run by a collective in Bushwick, hasn’t fully closed yet, but it has reduced its hours and stopped serving food. On Saturday, customers poured into the coral-colored room, buying out the store’s supply of Parable of the Sower, the first in a dystopian duology by Octavia Butler. “Everyone had that half-guilty look on their face, like, Should I be here? Should I be outside?” recalled María Herron, one of the store’s founders. “People’s anxiety was through the roof, and you could see it in the way they walked, in their shoulders and backs. But we talked about books, about poetry, and the relief and the rejuvenation was so palpable. In the face of the prospect of social isolation, people were just so excited to be social.” On Monday, she said that the collective was debating whether to reduce their hours or open their doors for appointments only. Either way, they are planning on ramping up book delivery service on bikes.

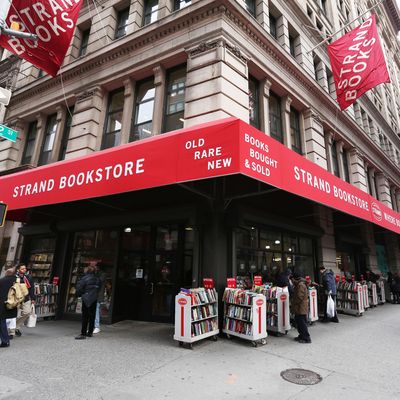

A few other bookstores in the city remain open — Barnes & Nobles is reducing its hours and is “prepared to close stores promptly along with guidance from local and national officials.” The Mysterious Bookshop, a speciality store in the Financial District, was open but empty, according to the manager, Tom Wickersham. Most other stores aren’t taking any chances. This week, no one will be rummaging through the discount racks beneath the iconic red-and-white signs of the Strand Bookstore on Broadway. It will be one of the only times in nearly a century that the store has gone dark. (It also closed during Sandy and for two weeks after 9/11.) “Everyone who works in retail is pretty freaked out about what the long-term implications will be for this,” said James Odum, the communications director for the store, “but we’re really focusing on what we can do for now and what the next seven days look like.” The Strand has not laid off any employees, but other bookstores, including McNally Jackson, have already taken that step.

Many of the shops are looking for creative solutions to stay open for online business, as well as the communities they’ve fostered. Astoria Bookshop, in Queens, is offering books for pickup. “The vast majority of our customers live in Astoria,” Lexi Beach, the owner, told me, “so if they’re well enough to go out for a walk, they can come to the store, knock on the door, we’ll have their book ready for them.” Beach was intrigued by an idea she’d seen on Twitter from a bookstore in D.C. that was offering customers exclusive occupancy of the store for one-hour time slots. “Indie bookstores are constantly stealing each other’s ideas,” she said. Mil Mundo was in the process of figuring out how to conduct its next book club on Google Hangouts — it planned to discuss Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. “We’re trying to think about the ways we can still be an inspiring space without the physical space,” she said. “There’s a silver lining to all of this — that we can reinvent how we talk about storytelling.”

On Monday, I spoke to Straub while she was in the midst of her first morning of homeschooling her kids. As predicted, her husband was at the store, and so far, the outlook was positive — they had 50 new orders waiting to be filled. Straub, who has a book of her own coming out in May, is also brainstorming how she can support authors during this strange and difficult time. “We’re talking about setting up virtual book tours,” she said. “The internet has always been a thing that we, as a store, have been good at, so I feel like this is the time for us to really use that force for good and try to shine the light on as many writers as we can.”

Meanwhile, at Idlewild, a bookstore specializing in travel books and language classes, the owner, David Del Vecchio, has begun experimenting with offering classes on Zoom. So far, he said, it had gone surprisingly well. “At first Zoom seemed like a compromise,” he wrote in an email, “but it works great for a small class. Even though it sucks not to be able to be in a room together, it’s not that different in some ways.” Last week, just before they made the choice to close their doors, a steady trickle of customers bought stacks of books. No one was buying travel guides, he said, but more customers were buying international fiction than usual. “People are just trying to maintain a connection to the world,” he said, “until it opens up again.”

We’re committed to keeping our readers informed.

We’ve removed our paywall from essential coronavirus news stories. Become a subscriber to support our journalists. Subscribe now.

More on Coronavirus

- Lil Wayne Gave More Than a Li’l Covid Relief Money to ‘Mystery Women’

- Andrew Cuomo Can Keep $5 Million for COVID-19 Book, Judge Rules

- Who Dares Talk Back to Patti LuPone at a Patti LuPone Talk-back?