When it came to perfectly portraying and satirizing blithe and unjustified self-confidence — the embodiment of white male privilege in America — no one fit the bill better than Fred Willard.

Willard, who died on May 15 at 86, was best known in recent years for his Emmy-nominated turns on Everybody Loves Raymond and Modern Family and for his priceless silliness in sketches on Jimmy Kimmel Live. But Willard had been earning laughs for nearly a half-century.

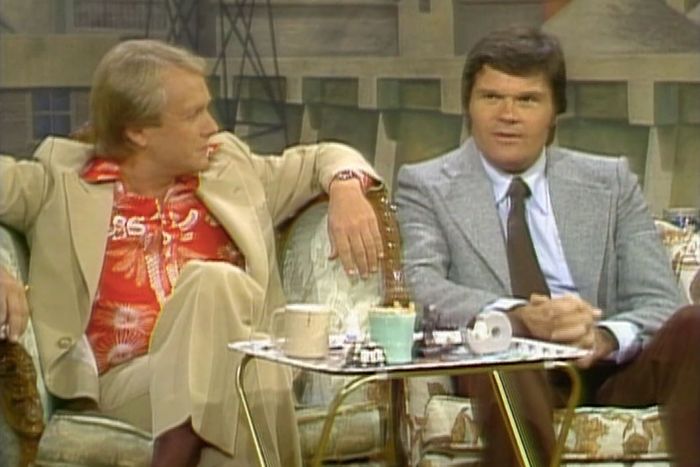

After honing his improvisational chops at Second City in the 1960s, Willard first started attracting attention in the sketch-comedy group Ace Trucking Company. But his real breakthrough came in 1977 as Jerry Hubbard, Martin Mull’s sidekick on the Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman spinoff Fernwood 2 Night. In the early 1980s, Willard became a favorite guest on Late Night With David Letterman; once he showed up “late” and had to change clothes onstage, “accidentally” ending up uncovered and pantsless. Another time, he brought a “co-guest” with him to even things out, since late-night hosts always had sidekicks; his gambit backfired spectacularly.

His first notable movie role was in This Is Spinal Tap, Rob Reiner’s 1984 mockumentary starring Christopher Guest, Harry Shearer, and Michael McKean. Willard’s onscreen time was brief, but he was unforgettable as an oblivious and smarmy military man, who manages to be both obsequious to and dismissive of the heavy metal band before their ill-advised performance at his base: “Better not get too close to you — they’ll think I’m part of the band. I’m joking, of course.”

When Guest directed his own mockumentaries, Willard was a perpetual scene-stealer: He was endearingly goofy as a married travel agent with a desire to perform (and who’d had “penis reduction surgery”) alongside Catherine O’Hara in 1996’s Waiting for Guffman; an obtuse and endlessly inappropriate dog show color commentator in 2000’s Best in Show (“I don’t think I could ever get used to being poked and prodded like that. I told my proctologist one time, ‘Why don’t you take me out to dinner and a movie sometime?’”); as a folk-band manager in 2003’s A Mighty Wind, he was marching to his own drummer and always out of tune (proposing a “literate reference” to Moby-Dick that involved props, waves, and getting the women singers’ shirts wet).

Willard was beloved not only by audiences but by those who worked with him, including Norman Lear, who gave Willard his first big break on Fernwood 2 Night, and Bob Balaban and John Michael Higgins, who were both regular members of Guest’s ensemble with Willard. All three spoke to Vulture about their memories of working with the late performer and what made his comedy so special.

Norman Lear: I had seen Fred with the Ace Trucking Company. I cast him in Fernwood 2 Night because he provided a perfect juxtaposition with Martin Mull, who played someone who was smug as hell and had all the answers. With Fred you always knew there was a decency there.

Martin and Fred clicked right away. When one walked into the room and the other was there, they both lit up. They worked so brilliantly together. I loved walking into rehearsal, knowing I was going to laugh as deeply as you can possibly laugh.

The show was 90 percent improvised. We had an outline on a subject and talked about the destination we wanted them to reach, but how they got there was how they got there. I remember giving them notes sometimes, but they were often surprising us in front of the audiences.

Fred Willard really was one of the good guys.

John Michael Higgins: Fred was a big influence on me. To some extent, I took over the roles he did. Some might call it stealing — guilty as charged. He didn’t break the mold, he made the mold of benign, confident stupidity in the American white male. This was not an angry stupid man; he was almost always happy in his stupidity.

He had a smile on his face. That was how Fred engaged with his performances, and in his life: When you saw him on, say, Late Night With David Letterman, there was always a twinkle in his eye, like he was saying “This will be fun,” not just for the audience but for him.

I first saw Fred in the Ace Trucking Company. I would search them out. You’d find a friend who had a copy of, say The Harrad Experiment — it was a terrible movie based on a salacious airport book that had only enough plot for half a movie, so the characters go to a nightclub and watch the Ace Trucking Company for a really long time.

Then, of course, came Fernwood 2 Night. I was fascinated by Fred: Is that real? Is he really that person with that attitude? It seemed so effortless, when really I learned later he was highly skilled with great observations, but [he] was a natural performer, so he could hide it so well.

We met before Best in Show as guests on some sitcom, and we were instantly simpatico. We work similarly: We are not fussy on the set; we just put our heads down and do the job, which doesn’t sound like a comedian. Fred was like a highly specialized machine with jokes and so accurate. He was a real resource, a spectacular compendium of vaudeville-type gags. He had that database in his head and had a setup and joke on any subject.

Harry Shearer and his wife hosted an annual variety show at Christmas. Fred would go out, dressed as, say, Elvis, and all these Elvis jokes just gushed out of him. I was with him backstage and he had no piece of paper with him; I’m sure if I’d said, “Woodrow Wilson. Go” he could fill a half hour with Woodrow Wilson jokes.

Fred was a great listener, which is crucial in improvising, but when you improvised with Fred usually he’d take the stern and you’d be happy to go along for a great ride. On Mighty Wind, he was our band’s manager, and at one point he was pitching us on ideas. I was the straight man there, and so much of it ended on the cutting-room floor because people could not stop laughing. I just couldn’t bear it and couldn’t hold it in. It was just a tsunami of stupidity. He was not trying to break us up — he was very professional that way — he just was giving Chris [Guest] a lot of choices with joke after joke. But the jokes were all funny.

Bob Balaban: The first time I worked with Fred was on Waiting for Guffman. He had first dented my consciousness with Fernwood 2 Night but really solidified his pantheon status for me with Spinal Tap.

So the way Chris Guest works is he writes an outline and then there’s no rehearsal; the cameras just roll. It’s wonderful because you know Chris has enough confidence in you to just let you go. In my first scene with Fred, I’m sitting at the table with Chris, who is playing Corky, and my character is hating the whole thing. Fred comes in with Catherine O’Hara as a couple to audition for the show. I had no idea what they were about to do, and they start performing “Midnight at the Oasis.” You knew immediately this was special. This wasn’t improvising — they had memorized the song and planned the choreography — but what was amazing is that it’s hard to come across as horrible at something but to be wonderfully horrible, and that’s what they were. It really got the movie off on the right foot. I still think about that scene all the time.

I can’t explain what it’s like to be in the room with Fred when he’s improvising. We had a scene in Best in Show where my character encounters Fred. Again, I don’t know what he’s about to say. He started talking about Columbus and the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria, but he gets everything wrong. I kept trying to correct him; I couldn’t get a word in edgewise. It’s like being run over by a truck — a very friendly truck. That’s the energy Fred had: His mind was going a million miles a minute and he had idea after idea. My heart was pounding; the adrenaline was pumping as he kept denying everything I said. You have to really listen carefully to him and hang on for dear life. It really was exciting.

When he was improvising, he didn’t use a funny voice or a different walk, he just was those characters. He had it so deep in his DNA and he really was so present in the moment when he was acting, just as much as Marlon Brando, so you couldn’t see he was acting or where it came from.

Offstage, there was such a contrast. He was so well-adjusted and happy. He and his wife, Mary, were the perfect match. He was eternally kind and thoughtful and didn’t interrupt. He wasn’t one of those comedians who need to occupy all the space in the room. Fred was as good as his reviews, both as a human and an actor.