Ryan Murphy has returned to the Old Hollywood well yet again with his latest Netflix show, but this time, there’s a twist. Although Hollywood features several real-life celebrities, directors, and agents, their biographies are intentionally pumped full of lies to suit the limited series’s alternative history, which imagines how life might’ve been different for queer, black, and brown entertainers if racism and homophobia were not barriers to their success.

The show follows a group of young, fictional creatives all trying to land their big break in postwar L.A. There’s Camille Washington (Laura Harrier), a black actress sick of being pigeonholed into roles as maids, and her half-Filipino director boyfriend Raymond Ainsley (Darren Criss), who desperately wants to resurrect the career of his screen idol. Then there are the boys at Ernie’s gas station, which is really a mobile brothel for the rich and famous. Wannabe actor Jack Castello (David Corenswet) reluctantly works there with black screenwriter Archie Coleman (Jeremy Pope), who begins seriously dating one of his clients, another would-be star named Rock Hudson (Jake Picking).

The changes Hollywood makes for its alternate history are mostly big and obvious — actresses who didn’t win Oscars do, closeted actors are public about their sexuality — but individual depictions do differ in other, less narratively necessary ways. Here, how Hollywood sticks to the script, and veers completely off it. (Historical spoilers ahead.)

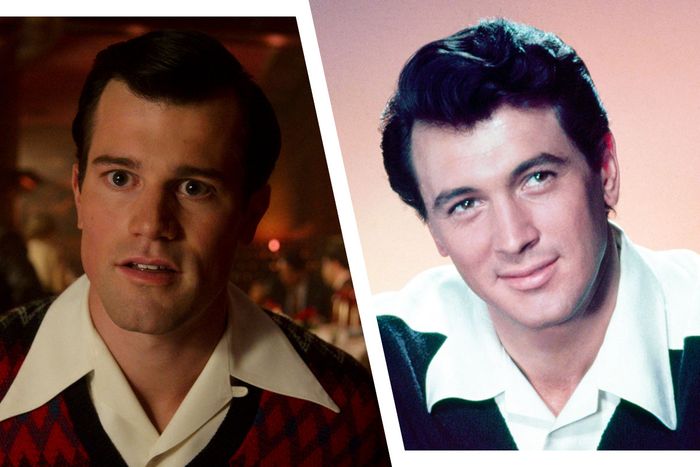

Rock Hudson (Played by Jake Picking)

Rock Hudson is the only principal cast member based on a real person, but in this reimagined Hollywood, he bears little resemblance to the actual celebrity. The basic biographical pieces are still there. Born Roy Scherer, Jr., Hudson fled an abusive household in Winnetka, Illinois, where his stepfather beat him for any perceived effeminate behavior, including asking for drama lessons. In his first meeting with career-making agent Henry Willson (we’ll get to him in a bit), the future star admitted he had no acting experience, and his honesty won Willson over. Hudson was also gay, though unlike his Netflix counterpart, he couldn’t exactly walk the red carpet with his boyfriend.

As biographer Mark Griffin writes in All That Heaven Allows, Hudson had a number of “short-term boyfriends,” but Willson pushed him to present as straight in public. In 1949, the agent fixed Hudson up on a date with the more famous Vera-Ellen at the Flashbulbers Ball, a fundraiser where plenty of paparazzi would be standing by to snap photos. (The couple went as Mr. and Mrs. Oscar, and wedding rumors swirled.) Things took a more drastic turn in 1955, however, when Hudson married Willson’s secretary Phyllis Gates, shortly after the tabloid Confidential nearly outed him. The couple divorced three years later. In a 1987 tell-all, Gates claimed she didn’t know about Hudson’s sexuality and had been tricked by her boss and ex-husband into the marriage, a claim various historians have disputed. Hudson’s sexuality would not become widespread public knowledge until 1985, when his publicist confirmed his AIDS diagnosis. He died from the disease that same year.

Biographers also paint the real Hudson as more ambitious than the fictionalized Rock, who mostly seems to stumble into parts through sheer luck. Oh, and that party scene where he doesn’t know who Scarlett O’Hara is? Considering how much he loved movies, yes, Rock Hudson definitely would’ve recognized Ms. Vivien Leigh.

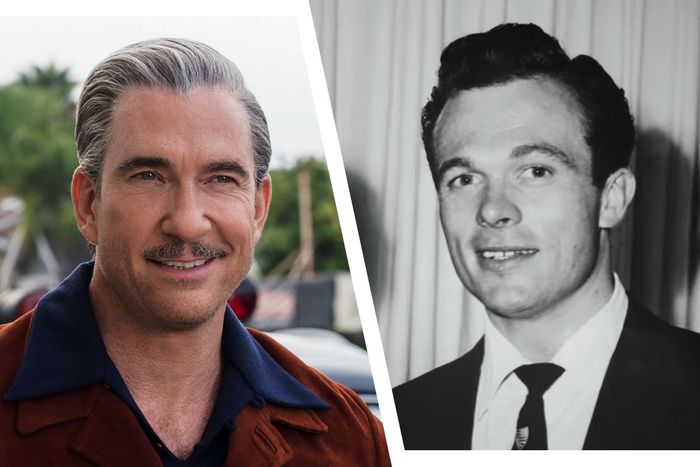

Henry Willson (Played by Jim Parsons)

According to one of his former clients, Henry Willson was known about town as a “lecherous gay Svengali” — and that was one of the nicer things people said about him. The agent specialized in plucking wholesome, all-American beefcakes out of obscurity and turning them into stars, but not before he pressured them for sexual favors in exchange for his help.

Hollywood contains multiples scenes of Willson manipulating his clients into solo dinner dates, group sex in his office, or watching as he performs a demented dance of the seven veils. Though Willson certainly preyed on his clients, it’s unlikely he behaved quite so cartoonishly: Willson biographer Robert Hofler does not reference any interest in drag in his book The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson, and he includes a much tamer account of Willson’s first meeting with Hudson than the one we see on the show. (The latter ends with Willson telling Hudson, “There is just one thing that we gotta get out of the way: I need to suck your cock.”)

As ex-client Tab Hunter writes in his 2005 memoir, Willson “believed that young women craved a male equivalent of the pinup stars who’d boosted the troop’s morale during the war” and considered “acting skill secondary to chiseled features and a fine physique.” Willson prowled nightclubs, skating rinks, and gas stations for new talent, branding his hires with snappy new stage names once they’d signed. (“Rock Hudson” was a combination of the Rock of Gibraltar and the Hudson River.) To protect his clients, several of whom were closeted, Willson carefully managed their star personas, often managing their social lives to convince the public they were straight.

But Willson could also use his PR savvy for spite. According to an infamous bit of Hollywood lore, Willson squashed an exposé of Hudson’s personal life by feeding the tabloids career-ending stories on two of his other clients: Rory Calhoun and Hunter, who had just fired him. Hudson biographer Mark Griffin couches this story with some caveats, noting that some believe Universal publicity chief Jack Diamond was the one who “intervened” on Hudson’s behalf, but he concedes that the story is “very credible based on how we know that Henry Willson operated within the industry.” This tabloid manipulation appears in the back half of Hollywood as well, when Willson kills a damaging story on fictional studio boss Avis Amberg (Patti LuPone).

Anna May Wong (Played by Michelle Krusiec)

Much of Anna May Wong’s story is revised in Hollywood to give her a happier biography, one that, like Rock Hudson, she might have claimed in a less bigoted industry. The Chinese-American actress was known for playing dragon ladies and other exoticized characters in both silent- and sound-era films. When MGM announced production on The Good Earth, however, Wong thought her chance to play a substantial role had finally arrived. The Pearl S. Buck novel centered on Wang Lung and O-Lan, married Chinese villagers trying to grow a farm and family. Wong wanted the role of O-Lan and wasn’t shy about it. When gossip columnist Louella Parsons asked her if she would be doing any more screen tests for the part, she joked, “I know I look Chinese and so does everyone else.” But after Paul Muni, a white actor, was cast as Wang Lung, Wong lost any consideration for the role, since the Production Code banned on-screen interracial relationships. The German-American actress Luise Rainer won the role of O-Lan instead, and went on to win an Oscar for it. Wong was offered a smaller role as yet another exoticized dancer named Lotus as a consolation, but she refused. “If you let me play O-Lan, I will be very glad,” she told MGM executive Irving Thalberg. “But you are asking me — with my Chinese blood — to do the only unsympathetic role in the picture, featuring an all-American cast, portraying Chinese characters.” In Hollywood, Wong wins an Oscar for her role in the fictional movie Meg, but in reality, this was the closest she ever came to an Academy Award.

Scotty Bowers (Played by Dylan McDermott)

Though he goes by Ernie West on the show, the silver-haired gas-station pimp who takes clients to “dreamland” is an homage to Scotty Bowers, the L.A. legend who passed away last year at the age of 96. His salacious memoir Full Service describes a prostitution ring catered to the closeted stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age, which Bowers ran out of a gas station on Hollywood Boulevard. Cary Grant and Bette Davis were supposedly clients, as well as the Duke of Windsor and his monarchy-busting wife Wallis Simpson. “Straight, gay, or bi; male or female; young or old,” Bowers writes. “Whatever folks wanted, I had it.”

While many doubt Bowers’s wild stories, director Matt Tyrnauer boosted his tales in the acclaimed 2017 documentary Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood. On-screen, Bowers is loud, lewd, and impish — a self-appointed historian who delights in torching sanitized perceptions of Old Hollywood. In other words, a perfect Ryan Murphy character.

George Cukor (Played by Daniel London)

George Cukor the character doesn’t make much of an impression in Hollywood, but the real-life director is weirdly crucial to the plot, since his legendary soirees figure prominently in the show. The filmmaker behind Gaslight, The Philadelphia Story, and many other so-called women’s pictures, Cukor spent his Sundays hosting “afternoon pool parties that were unabashedly all-boy affairs.” His home — decorated by Billy Haines — became a haven for queer creatives like himself, who were whispered about in Hollywood but stayed in the closet publicly to remain in business.

Tallulah Bankhead (Played by Paget Brewster)

On Hollywood, no one has more fun than Tallulah Bankhead. In one scene, she’s snorting cocaine — and laughing hysterically — in the hallway of a friend’s mansion. In another, she’s teasing two men in robes, as they sit on either side of her and rub her bare legs. “By midnight, most of the ladies have gone home,” Ernie says, describing Cukor’s parties. “But Tallulah usually sticks around.”

The real Tallulah Bankhead was well aware of her debaucherous reputation. “Despite what all you may have heard to the contrary, I never had to ride in a patrol wagon,” she writes in the first line of her 1952 autobiography, before listing out all the things she has done. (Milked a mammoth, climbed an elephant, and done an “Indian rope trick” while drunk on daiquiris, to name a few.) She was unusually candid about her personal life, which likely contributed to her decline in work in the mid-1930s, as morality clauses and censorship overtook the industry. An actress of the stage and screen as well as a member of the Algonquin Round Table, Bankhead liked to joke that she was “pure as the driven slush” — a line repeated by her Netflix avatar in episode three.

Hattie McDaniel (Played by Queen Latifah)

When Hattie McDaniel first appears in Hollywood, she’s enjoying a home-cooked breakfast, prepared by the buff, shirtless “gas-station attendant” standing in her kitchen. He leaves, but not before Tallulah Bankhead saunters in to give Hattie a quick peck on the lips. This scene nods to McDaniel’s rumored bisexuality, as well as age-old gossip about what exactly Tallulah Bankhead meant when she called McDaniel her “best friend.” But the show spends more time on the moment that defined McDaniel’s career and indeed her entire life: her 1940 Oscar for Gone With the Wind.

McDaniel’s performance as Mammy made her the first black Academy Award winner in history, but she was still sidelined even in victory. Seated at a separate table away from her co-stars, McDaniel accepted her statuette in a segregated hotel, and received almost nothing but offers to play more maids and mammies after her historic achievement. Hollywood imagines a fictional black actress busting down the doors on her own Oscar night — and leaving them open for her mentor McDaniel to finally walk through.

Vivien Leigh (Played by Katie McGuinness)

McDaniel’s Gone With the Wind costar Vivien Leigh also makes a cameo at Cukor’s party, wearing a deep-green dress stolen straight out of Scarlett O’Hara’s closet. The show recreates a story about the actress from Full Service almost word-for-word, wherein Bowers (here, Ernie) and Leigh have an intimate encounter at Cukor’s house. Bowers’ details — that Leigh was about to start work on A Streetcar Named Desire, that “Larry” (her husband, Laurence Olivier) was away, that he had noticed her “mood swings” at dinner parties — are all folded in through quick bits of dialogue.

The “mood swings,” emphasized more dramatically on the show, refer to Leigh’s struggles with bipolar disorder, or what would’ve been called manic depression in her day. Friends and colleagues were concerned about Leigh’s mental state as early as 1937, according to biographer Kendra Bean, though few knew what they could do to help. “I never saw any cruelty or coldness in Vivien — even her ambitions and her needs were dealt with charmingly and sweetly, insofar as my witness can bear,” Alec Guinness recalled. “It was very sad. She appeared, at a very young age, to turn into a lovely stalk of chalk, and the chipping away had begun, and you were there to see the flaking off.”

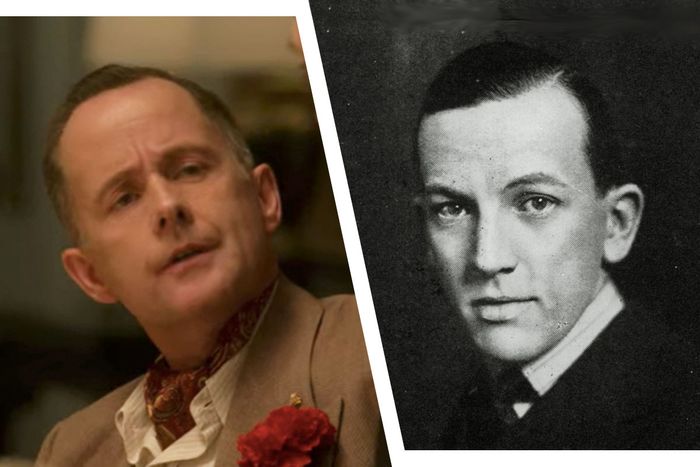

Noël Coward (Played by Billy Boyd)

“Don’t get the wrong idea, I’m not a heavy drinker. Sometimes I can go for hours without touching a drop.” That’s the opening line Noël Coward uses on Archie at Cukor’s party in Hollywood, and it’s an apt distillation of the famously droll writer-actor-composer. Coward was an astonishingly prolific playwright and performer on the London stage. Over the course of his life, he wrote nearly three dozen plays and musicals, usually satires of high society that made for perfectly frothy films. Producers in Britain and Hollywood began buying up his comedies in the silent era, but Coward wasn’t content to merely sign his rights away. He worked as a producer, screenwriter, and actor on both sides of the pond. In Full Service, Bowers claims Coward was a frequent customer; he was also a noted guest at Cukor’s pool parties.

Peg Entwistle

On September 16, 1932, Peg Entwistle climbed a ladder to the top of the “Hollywoodland” sign, stood atop the 50-foot-tall H, and leapt to her death. The shocking true story became the default allegory for the destructive nature of Tinseltown, and on Hollywood, it’s the basis of Archie’s industry-changing blockbuster Meg.

Entwistle began acting as a teenager, booking consistent work on Broadway before she moved to Los Angeles to star in The Mad Hopes with Billie Burke and Humphrey Bogart. She got great notices for that stage production, and the buzz soon reached legendary producer David O. Selznick. As recounted in Peg Entwistle and the Hollywood Sign Suicide, Selznick urged Cukor to consider her for the comedy A Bill of Divorcement. She didn’t get the part (it went to Katharine Hepburn), but she signed a one-picture deal with RKO to make her first movie, Thirteen Women. Entwistle’s screen time was slashed from 16 minutes to 4, a setback that Hollywood includes in Archie’s fake script, but unlike the Peg in that story, she didn’t have a concerned boyfriend chasing after her. Her marriage to the alcoholic and abusive Robert Keith ended in 1929, and news of his remarriage — along with her professional disappointments — devastated the young actress. She died before Thirteen Women was released.