A week ago on Twitter, Carl Reiner remarked that he was proudest of two pieces of his work: the 2000-Year-Old Man sketches he’d recorded with Mel Brooks, and creating The Dick Van Dyke Show. They seem only nominally related: One was a recurring improv bit in which Reiner was the ostensibly colorless straight-man interviewer, and the other was a slick CBS sitcom in which Reiner played a splenetic character named Alan Brady. But what they have in common is the writers’ room, that mythic place in the making of comedy where the funny comes from. Reiner and Brooks had met on Your Show of Shows, the Sid Caesar–Imogene Coca sketch show of the early 1950s, where Reiner wrote and performed, and Brooks got started as a writer; they’d worked out the 2000-Year-Old Man there. And The Dick Van Dyke Show was set backstage at a show very much like Caesar’s, in which Morey Amsterdam played a version of Mel Brooks, and Reiner played a hectoring star who seemed quite a bit like his old boss. Until Reiner came along, nobody outside the business knew about the writers’ room; today we all do. It’s a straight line from there to the behind-the-scenes scenes of Saturday Night Live, or to 30 Rock, or to so many other great, funny pieces of our culture. Social media, where dunking on people is a pastime, constitutes one giant, worldwide amateur writers’ room.

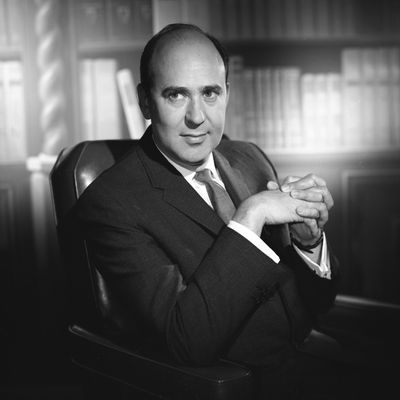

Well, you can’t credit him with (or blame him for) Twitter, but for those other two inarguable achievements alone, we’d be celebrating Carl Reiner, who died late yesterday at 98. But his greatness hardly stops there. In eight decades as a performer, he almost always seemed to be an enthusiast, a playful maker of comedy rather than a sad clown or misanthropic one. (He was, as a public figure, the anti–Larry David.) His timing was as good as absolutely anyone’s — watch any interview with him; the man could tell a story as well as anyone — and he was generous with it, because as often as not, he played the straight man, setting up other performers to run free. And when he did step into the comic’s role, he killed.

Being a great straight man is an underrated skill, because it’s easy to mistake it for merely facilitating some other genius’s jokes. But it requires at least as much dexterity, because you have to (to appropriate the old Wayne Gretzky line) see where the puck is going and skate there, setting up your partner’s lines while also thinking ahead to your next one. Consider the sketch on the album 2000 and Thirteen in which he enables a joke about Paul Revere, sees where Brooks is going, sets up the punch line, and then draws it out with reactions for a solid minute:

Reiner could work high and low, brainy and broad. After getting started as a performer in Broadway revues of the 1940s, he joined Caesar’s show in 1950, and its sketches were often pretty cerebral: jokes about Beat poetry, opera parodies, spoofs of foreign-film artiness. Reiner was onscreen every week and also contributed to the writing, and you can watch his almost-unbelievable ability to keep it together in this highly elevated sketch where Caesar got all the laughs: Reiner’s slightly anxious but soldiering-through character, trying to hold his composure as his TV show is disintegrating, is a master class in keeping it together.

As for that other great creation, Reiner rather than Brooks was the man who got it started. “Here’s a man who was at the scene of the Crucifixion 2000 years ago. Sir?” was the question he idly proposed one afternoon, turning to Mel Brooks for an answer. Brooks leaned in — he began with a weary “Ohhh, boy” — and five albums, TV appearances, an animated special, and a book eventually followed. Cary Grant once told Brooks that he’d played their first LP at Buckingham Palace, and the Queen Mother had loved it. Once again, Reiner was playing it absolutely deadpan, although he is not without personality; watch his response to the “cheese” joke, which he’s just set up — probably with an idea of the punch line — but also reacts to like an audience member hearing it for the first time.

He could do the broadest comedy as well, the kind of seemingly idiotic material that is secretly smart, of a kind that takes real intelligence to create. Exhibit A is The Jerk, a film where he, as director, once again knew how to set up an extremely funny man, Steve Martin, and let him deliver. There’s a lot in that movie that depends on its setup and direction as much as on its performances (the “This is all I need” scene comes to mind), and he followed that up with three more Martin films and made a double handful of other broad comedies — some of them only okay but at least two of them (Oh God!, with George Burns as the Supreme Being, and All of Me, a body-switching comedy with Martin and Lily Tomlin) are charmers.

And of course there’s The Dick Van Dyke Show. The vaguely postmodern idea of a show-about-the-making-of-a-show was newish in 1961, and Dick Van Dyke’s cheery, open comedic persona was a good analogue for Reiner’s. By contrast, Reiner himself — after trying on the starring role for the pilot, then wisely ceding it — took the role of the fictional program’s host, Alan Brady, a shout-y, impossible boss who was obsessed with hiding his hairpieces and ordering his deputy to “Shut up, Mel.” Reiner had cast himself a little bit against type, and reveled in it. The show’s scripts were quite inventive, given the limits of the early-’60s sitcom: One episode, “It May Look Like a Walnut,” is vaguely Twilight Zone–ish, and the series’ overall portrait of Rob and Laura’s marriage is relatively open and realistic; they don’t seem to inflict tortures on one another, the way a lot of sitcom couples do. (Van Dyke once said that, for the first time watching a sitcom, “you actually believed that Rob and Laura did get it on.”) Maybe that was because Reiner had a good family life of his own. He was married to the same woman for 64 years, and his wife, Estelle, gained a bit of late-in-life fame when their son Rob put her in his own film, When Harry Met Sally … She’s the one who says, “I’ll have what she’s having.”

Not just his marriage but his whole life became fodder. Enter Laughing, his 1958 semi-autobiographical novel about his young adulthood, eventually became a Broadway play and then even a musical. His first TV credit is from 1948, a year after the major networks went on the air; his last is from 2019, spanning the entire era of the medium. Reiner also got himself a little extra later-in-life movie-star recognition of his own, when he was (perfectly) cast as Saul Bloom in the Ocean’s Eleven movies, as a dyspeptic, deadpan old hand with a funky wardrobe. And, in fact, his final few years found him one more outlet: Twitter itself, where he was perhaps the oldest truly great user of the medium. The global writers’ room accommodated his voice well, and he could participate from his Barcalounger in Beverly Hills, making mincemeat of Donald Trump on a regular basis and getting off a genuinely funny tweet every couple of days. He seemed to have an unexpectedly youthful outlook: When one of my Vulture colleagues asked him last year who the funniest people to follow on Twitter were, he wasn’t dismissive in that old-guy “nobody’s funny anymore” kind of way: Instead he responded “Judd Apatow, Sarah Silverman, Amy Schumer. Mel Brooks, when he tweets. Rob Reiner, of course.” A few days ago, he and Brooks posed with Reiner’s daughter, Annie, in T-shirts reading BLACK LIVES MATTER — once again, using his understated fame to showcase something worth seeing. And one of the very last things he wrote, three days ago, suggests the same generosity of spirit:

More From This Series

- Revisit Carl Reiner’s Very First Conan Interview From 1995

- In Pictures: The 70-Year Career of Carl Reiner

- Rob Reiner, Mel Brooks, Alan Alda, and More Celebs Share Tributes to Carl Reiner