There’s a slight disconnect in the fact that the Bruce Lee documentary Be Water is airing on ESPN in the time slot where the ten-part Michael Jordan series The Last Dance recently reigned supreme for five weeks straight. The channel’s attempt to continue capitalizing on sports-deprived viewers’ hunger for docs about transformational athletes is certainly understandable — they’ve already aired a two-part film about Lance Armstrong, and next week we’re getting one about Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire — but the intimacy, lyricism, and righteous rage of Be Water are miles away from the corporate, apolitical sheen and gabby back-and-forth of The Last Dance. Be Water doesn’t feel like a sports doc at all; you walk away from it convinced that Bruce Lee was an artist more than anything else.

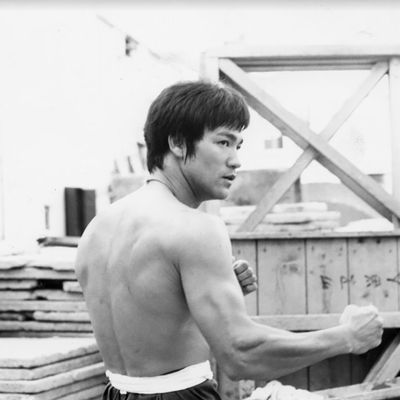

Directed by Bao Nguyen, Be Water follows Lee’s story via the voices of those who knew him, as well as film critics and historians (we don’t see any of the interviewees’ present-day faces until the end credits) while nimbly weaving the martial artist and actor’s life with a broader context for his career and stardom. Passages from Bruce’s diaries are read by his daughter, Shannon Lee. The title refers to Lee’s own revelation, which he claims happened as he rode a junk by himself as a teen in Hong Kong harbor, punching the water in frustration, that the true way to fight was to be like water. “The softest substance in the world only seems weak,” he observes. “In reality, it could penetrate the hardest substance in the world.” This led to a style of fighting that had the formal elegance, physical majesty, and artful unpredictability of dance. And watching it all come together is intoxicating. At one point, the film cuts between Lee fighting Chuck Norris in Way of the Dragon and Muhammad Ali fighting Cleveland Williams in 1966. Lee himself was fascinated by Ali, and while the moves aren’t the same, the energy certainly is; a personality emerges from the action, and the fight becomes less about defeating an opponent and more a form of expression.

Lee was ambitious, proud, even boastful. He had to be. It would not have been possible to accomplish what he did by being shy or playing hard to get. He wanted to become an Asian leading man at a time when pretty much all stars in Hollywood were white. Good-looking, charismatic, and enormously talented, he could get in the door, and get parts — he loved the camera, and it loved him back — but he still found himself running up against the racism of the film industry and the society at large. He refused to take roles that he considered demeaning to Asians. And he was denied roles that were tailor-made for him: One of the film’s most moving sections involves Lee’s developing the series that would become Kung Fu as a starring vehicle for himself, only to see the lead role go to David Carradine. Interviewed about it at the time, Lee admits his frustration but also expresses understanding about the white executives’ challenges. “I don’t blame them,” he says. “In the same way it’s like in Hong Kong if a foreigner came and became a star, and if I were the man with the money, I probably would have my own worries.” Despite his conciliatory words, we can tell that this one really hurts. (The show Lee envisioned, called The Warrior, was revived many years later and premiered last year on Cinemax.)

The story of Bruce Lee is compelling enough to have already fueled several fiction films, but Be Water’s structure is more psychological and emotional than it is biographical. It begins on his return to Hong Kong in 1971 and his two starring triumphs, The Big Boss and Fist of Fury, then flashes back to his arrival in the U.S. in 1959, and his time in the early 1960s teaching martial arts in Seattle. The voice of an old Japanese-American girlfriend, Amy Sanbo, flashes back to the Japanese internment camps of World War II, and then further back to the arrival of Chinese in America. We don’t hear much about Lee’s early career in the Hong Kong film industry until his future wife, Linda, learns about it herself when he takes her out one night to see The Orphan, a 1960 movie which she’s startled to discover stars Bruce himself. That in turn leads us into a further biographical passage about Lee’s childhood and his early troubles as a teen, which prompted his father to send him off to the U.S., the land of Bruce’s birth (his family had returned to Hong Kong when he was three months old). Along the way, we see Bruce’s image fighting against a history of demeaning Asian stereotypes, from caricatures about coolies to condescending myths about “model minorities.”

There is only so much one can do in 96 minutes, of course, and the film does play a little coy with certain matters, including later rumors of infidelity and just exactly what kind of trouble Bruce got into as a teen that prompted him to be shipped off to America (a question which has inspired numerous conspiracy theories). This is a surprisingly intricate structure, but it’s also wonderfully smooth — you feel like you’re part of an intimate, organic conversation about a complicated man and his times, rather than a history lesson, or a boilerplate bio-doc. The film itself moves … wait for it … like water.

Some interviewees suggest that the Bruce Lee myth might not have emerged had he not died so young; he was 32 when he passed away suddenly, likely due to an allergic reaction to a painkiller he’d been given for a migraine. Perhaps. His greatest success, Enter the Dragon, the film that would truly make him an international star, was released just days later and went stratospheric. In death, Bruce Lee became a global figure, as transformative as Ali, or Chaplin, or, yes, Michael Jordan. But when you see his sheer charisma, his drive, his unfathomable talent as well as his deep understanding of how to use that talent, you realize that, had he lived, he very well might have become an even greater, more revolutionary figure.

More Movie Reviews

- Fernanda Torres Is a Subtle Marvel in I’m Still Here

- Grand Theft Hamlet Is a Delightful Putting-on-a-Show Documentary

- Presence Is the Best Thing Steven Soderbergh’s Done in Ages