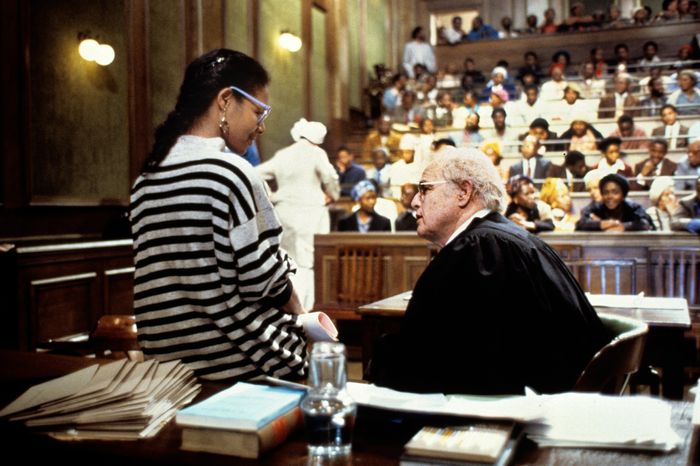

When anyone talks about A Dry White Season, they usually take care to make two points: It was the first Hollywood studio movie to be directed by a Black woman, and it was the project that brought Marlon Brando out of an eight-year absence from feature films. While both points are true, they reduce the actual work: A Dry White Season is vivid, urgent filmmaking that still sears the mind. It’s a thriller, it’s a caper, it’s a drama: A white South African teacher, Ben du Toit (Donald Sutherland), becomes radicalized after the child son of his school’s gardener goes missing and turns up dead. He can no longer ignore the realities of apartheid and the human cost of a racist police force. He joins forces with a local activist, Stanley (Zakes Mokae); a lawyer (Marlon Brando); and a journalist (Susan Sarandon) to expose the murderous police captain. The white protagonist delivers subversive messages about complicity and privilege; but in the end, writer-director Euzhan Palcy lets her Black hero have the last word.

The 1989 film is as relevant a watch now as ever: Anti-police protests have erupted around the globe over police killings of innocent Black women and men. In Hollywood, in the early 1980s, Palcy was one of the only Black voices. Her first feature, 1983’s Sugar Cane Alley, had executives begging the Paris-based filmmaker to come to California. She’d been mentored by François Truffaut, and had become the darling of festivals around the world. Ultimately, Robert Redford convinced her to make the trip to Los Angeles, and she agreed to work with a major studio — if she could adapt André Brink’s anti-apartheid novel and build out its Black characters. The movie was first developed at Warner Brothers, until the studio shelved the film because another feature about apartheid, Cry Freedom, was releasing around the same time. The project then moved to MGM, where Palcy says she got to make the movie she wanted: “I put my life in danger to make this movie, over and over,” she tells me over the phone one recent afternoon. “I went undercover in Soweto to hear these people’s stories. And I’d say to myself, If I cannot make this movie, I don’t deserve to be Euzhan Palcy. I don’t deserve to be a filmmaker!”

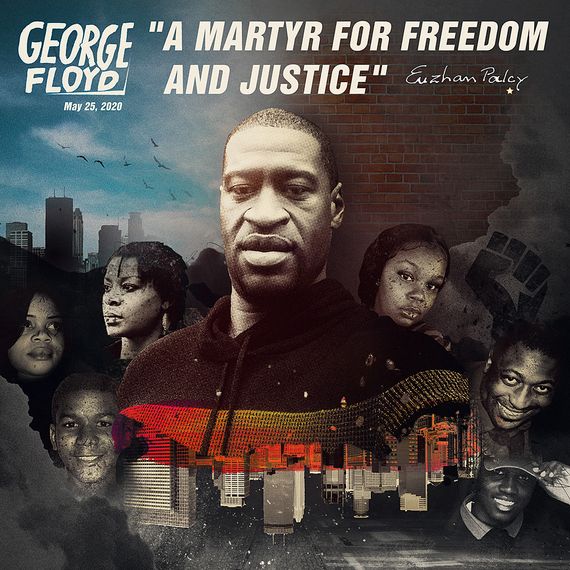

Palcy’s 2001 movie The Killing Yard, based on events surrounding the Attica prison riot in 1971, dealt with American racism more directly, but A Dry White Season was all about toppling a corrupt police state. “What the police are doing right now in America is what they were doing [in South Africa],” Palcy says from her home in France. “I used to say my camera is my miraculous weapon.” She spoke to Vulture about the making of her major Hollywood film, fighting with studios in the entertainment industry decades ago, and how George Floyd’s death has added momentum to a movement.

After Sugar Cane Alley, when Robert Redford chose you to participate in the Sundance Directors Lab, you weren’t really interested in going to Hollywood. Why?

No, I didn’t want to go to Hollywood. [Laughs.] I wasn’t sure that I would be able to do what I really wanted to do. I knew why I was making movies, and I knew the kind of movies that Hollywood was making. There was no room for Black folks there. Or if there was room, there was always going to be bad characters: not nice people or not intelligent people. I didn’t want to go through that.

They would offer me this and that, but there were no Black folks in the stories they were throwing at me. They loved Sugar Cane Alley, they wanted to work with me, but they didn’t want my ideas. I turned down so many projects, because I felt like if I did them I would betray the reason I decided to be a filmmaker in the first place. I felt like when the machinery opened its doors to me, I had to fight! I felt that I had to try to convince them: Why don’t you want those stories? Our stories? They are universal! I didn’t understand. “Give it a try,” I said, “Give me a try! Look at Sugar Cane Alley!” Give me projects with Black folks and white folks together and I’m happy. But all the studio projects were all all-white films. I was so sad, so sad about it. I just couldn’t do it. I was miserable. They wouldn’t understand why I was feeling that way.

So after Sugar Cane Alley —

I suffered so much to make Sugar Cane Alley. It was really hard because of racism, because of sexism, you know. I was Black, I was female — that’s considered a handicap in some societies. But I had strong, strong roots. My grandmother was a warrior. She taught me two things: Don’t let anyone get you off track from your dream, and if they put a fence in front of you, just jump over it and fly. I was ready. I was happy, but the struggle was so tough. After the success of Sugar Cane Alley, I was exhausted. So exhausted, from so many years of struggle. I was spent. I didn’t have any joy. People would say, “Your movie is highly successful, all over the world people are talking about it! You have so many awards but you seem sad. What is going on?” I was not sad. I was happy. It’s just that I was tired.

Sometimes I would cry. At screenings in New York, in Atlanta, people would be grabbing you, hugging you, kissing you, in tears, saying, “Oh my God! At last, at last we are on the screen. Black folks with their pygmy teeth, they are brown and they are beautiful and they are smiling!” They’d thank me. It makes me emotional even today. I remember those moments. I’m sorry — [Begins to cry.]

That’s okay.

I remember those moments. I was struggling to do it, but I knew it was so important to make that movie. I was sick of seeing Black folks in decorative parts. People don’t know about us, they don’t know who we are. I had to make that movie. If I could not make that movie then — gosh! My life was on fire. I saw how people were hungry and thirsting to see themselves onscreen, just like I was when I was 10 years old. It made me emotional. That’s why I wanted to be a filmmaker: to talk about us.

What changed your mind about going to Hollywood?

I had the book A Dry White Season, and Robert Redford and I had a long conversation. We were sitting on the grass, talking about what I wanted to do next and how I should do it. I showed him the letters Lucy Fisher from Warner Brothers had been sending me. She called me, and I told her that I couldn’t come [to Hollywood]. But she wrote me something like five letters that I kept, preciously. He looked at them and he said, “Euzhan. Listen to me. You have to go. Maybe that woman will hear you.” His office booked me a flight. I’m telling you that I love him because he did something that changed the course of my career.

So what happened next? Is this when you pitched her your version of The Color Purple?

Yes, The Color Purple book was sent to me. So I told her, “Okay, what about this story?” She said, “Oh, that’s too bad! We already have somebody doing it!” But she didn’t tell me who it was. Another time, you won’t believe what she put on the table: She gave me a script for Malcolm X. This was way before Spike Lee was on it, in 1986. They had a version of Malcolm X, their version of Malcolm X.

But you said no?

Of course I love Malcolm X and I know history by heart, but I believed that this should be done by an African-American. I don’t want to take that opportunity away from them. Somebody from that community should be doing it. And she said, “I disagree with you. I don’t know what to do, I’m so sad.” But I said, “No, you didn’t ask me if I had something that I want to do …” [Laughs.] Somebody already had The Color Purple, but I had another book I wanted to make something out of. I put the book on the table for her. It was A Dry White Season. I pitched the story. She kept me in town for a week. She gave me a driver to take me around Hollywood, on the Universal Studios tour, to take me out, just to keep me busy while she read the book.

And then what happened?

She called me and she said, “Okay, I have finished the book.” She took me to lunch with something like eight female producers, and they asked me to tell them my vision for the film. So I did.

How did you describe your vision?

I told them the story, and then I told them how I wanted to complete the book’s story. When André Brink wrote that book, it was a story of a white man: how that white man came to awareness, the story of a white Afrikaner’s awakening. My vision was a little different. I decided to tell the story in a way that showed his journey of blindness to consciousness, but I also wanted to tell the story of two families in South Africa. What happens when a man from [the white] community becomes aware? But also, what’s been happening to the Black people in the community? For me, it’s a story of two families, two communities.

There’s also that great supporting character, Stanley, played by Zakes Mokae. Tell me about writing that character.

Stanley was a cab driver and he was an activist. He’s a smart guy. He knows how to play the game. When he and Ben Du Toit become friends, Ben asks him, “Who are you, Stanley?” I made Stanley answer, “A mean Black cat in the night!” [Laughs.] Stanley is a very prominent character for me. He symbolized all the Black community of people fighting undercover against apartheid. They gave me what I wanted when I was making a movie.

But it became bad when I came to the studios pitching a movie about Bessie Coleman [an early American civil aviator who was the first African American woman and also the first woman of Native American descent to hold a pilot license]. They would say, “There are too many Black folks there! They are too many Black people in the lead! And female? No, no, no, no!” It was important to me to have Black folks that weren’t motherfuckers in the movies. That’s the kind of character we saw all the time: the motherfuckers, the junkies, the diseased, the this, the that. Characters like Stanley!

And Zakes Mokae was actually South African.

That was very important to me. The same way that I wanted a white guy to talk to his own community, I wanted to put the spotlight on the Black folks and give them a voice. It was absolutely important for me to use South African actors portraying themselves, with their own accents, their own way of walking. With all my love for Black American actors, I couldn’t take that opportunity away from the Black South African actor. I had to fight for that.

At the end of A Dry White Season, Stanley, a Black man, gets to shoot an evil white man. Was there any pushback in Hollywood to that ending? It still feels radical, by today’s studio standards.

That’s why I used to say that my movie A Dry White Season is a Hollywood production, but not a Hollywood film. I was very lucky, very lucky to have the producer that I had. Your question is very important. When I started to do press conferences in America, people asked, “Why did you choose that ending? What do you mean by that? Are you pushing for Black folks to take up arms and kill the white people?” Why would they think that? Is that all they think about? What I wanted to say that if white people think apartheid isn’t their business, if they don’t put pressure on their government, this is what will happen. You don’t know how many times I was asked that! They worked together, and Ben died, but Stanley got justice. They exposed the police. That’s why I have that ending.

Wow.

I just put the facts there in front of people, and said, This is it. When I see what happened now with George Floyd, what is happening with Colin Kaepernick — you see the result? When I see white people seeing the light, I cry. Oh my God. Do you know how long we’ve been fighting for that?

Did you feel lonely as one of the few Black filmmakers working in Hollywood in the early ’80s?

I was lonely! I was very lonely because I had no support. I have no support. Nobody supported me. I had that conversation with my dear friend Ava DuVernay. I tell Shonda [Rhimes] the same thing. I told them, “I’m so proud of you guys. I’m so proud of you because every single thing that I fought for, struggled for, spent my life building, paved for you guys and I’m so happy I did.”

Do you think that the studios treated you differently as a Black European, as opposed to an African-American?

Yes. I was the first Black female filmmaker working in Hollywood. I have to be honest with you: Every studio I worked with treated me like a queen. I fought with some of them, not all, but I had to fight to make my point. And I did. I would only compromise to a certain extent.

Now, with new platforms, there’s been an evolution. In TV series, there’s no problem to have all different kinds of people play the leads. What’s wrong with Hollywood’s feature films? They treated me like a queen when I made movies with them, but when they heard my ideas, they changed the game. We need more Black directors, more female directors, more of everyone working together. I think this movement, and the death of George Floyd, will bring that. Those people at the studio will have to understand that [the old ways] are over. That time is over now.