To watch Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter is to take a master class in image construction. In 2011, she severed professional ties with her father and former manager, Mathew Knowles, who’d had a strong hand in controlling her image. In the nine years since, she has evolved dramatically as a star. She’s almost entirely stopped giving interviews and instead communicates who she is as an artist through images. Beyoncé’s image-making over this period has been lauded for speaking meaningfully to the political moment. Looking closely at some of the most formative visuals of her career tells a more complicated story about the artist.

2011: Mother

“Love On Top”

MTV Video Music Awards performance

Beyoncé’s performance of “Love on Top,” a single from the album 4, is incandescent and high energy in the ways we’ve come to expect from her. The lasting image comes at its end: The singing is over, the backup dancers are cast in shadow, and Beyoncé is in the spotlight. She drops her mic, unbuttons her glittering purple blazer, and rubs her pregnant belly, signaling to the world the next stage in her life. This moment marked a turning point in how Beyoncé chooses to incorporate her family into her art, which in recent years has been undergirded by her interest in creating a lasting legacy. This is the first time she presented the public with the type of image that has come to define her career: a gleaming, aspirational snapshot of a Black family.

2013: Reluctant Speaker

Life Is But a Dream

Documentary

This HBO documentary, which Beyoncé co-directed and produced, is primed on the illusion of revealing the woman behind the pop diva. It’s an intriguing failure in her career. The image of a stripped-down, makeup-free Beyoncé speaking from a couch to an on-camera interviewer speaks most profoundly to what she struggles to communicate: intimacy. Life Is But a Dream has a veneer of vulnerability as Beyoncé discusses her marriage, her severing of professional ties to her father, even the rumors that she had a surrogate for her first pregnancy. But instead of revealing much about the star, it shows she doesn’t really have much that’s meaningful to say on her own. In many ways, the best thing Beyoncé ever did for her career was to stop doing traditional interviews (in which I include Life Is But a Dream) and instead let her art speak for her. This allows audiences to project a depth and complexity onto Beyoncé and her work that wouldn’t otherwise exist in the same way.

2014: Political Leader

“Flawless”

MTV Video Music Awards performance

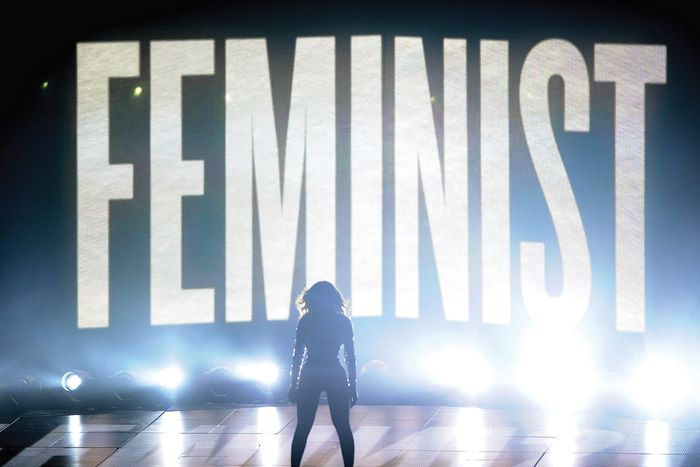

In the early 2010s, it was common to ask female stars if they were feminists, almost as a gotcha. What has been intriguing about feminism’s public image over the past 40 years is how it went from being a brand that women didn’t want to embrace for fear of retribution to a necessary political sheen. At the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards ceremony, where she received the Vanguard Award, Beyoncé performed a medley of songs from her self-titled album while wearing a bejeweled Tom Ford bodysuit. In a much circulated image, she stands in silhouette against the brightly lit word “feminist,” while Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s words from her 2012 Ted Talk, “We Should All Be Feminists,” blares out to the audience.

Before this album, Beyoncé’s relationship to feminism very much fit into the simplistic, inoffensive, and highly marketable sort of girl power that was a vestige of the 1990s and early aughts. In the years since, the veneer of feminism has proved useful for Beyoncé, allowing her to seem like a richly political figure. In her Life Is But a Dream doc, Beyoncé notes, “It really pisses me off that women don’t get the same opportunities as men do. Or money for that matter because let’s face it, money gives men the power to run the show.” That’s the extent of what we knew about Beyoncé’s feminism, capitalist minded and maybe even a touch conservative in its possibilities. But with this performance, the blandest language of the movement was enough to refashion her image as a bold political thinker.

2014: Capitalist

Run

Short film, and On the Run Tour film

The most striking moment in Run shows Beyoncé floating in a pool, surrounded by $100 bills that dapple the surface. It’s an image of exorbitant wealth. It is also paired with moments of intimacy between Beyoncé and Jay-Z in the On the Run Tour film, in which they stare intently at each other, as she tenderly strokes his arm. The aesthetics of the film and the tour evoke the movie Bonnie and Clyde, communicating an “us against the world” dynamic that aims to show they’ve traveled through the fire (the tour started not long after the infamous Met Gala elevator incident between Jay-Z and Solange went public) and come out the other side stronger. Both Run and the corresponding tour film are windows into how Beyoncé wants people to view her marriage: egregiously rich, powerful, united. But looking closely at the images she chooses to share often has the opposite effect; it highlights the ways this couple seems to be more like a meeting of two brands than a genuinely loving relationship anyone would aspire to.

2016: Representational Force

Lemonade

Visual Album

Lemonade is a resplendent work full of such striking imagery it’s hard to home in on a single one. The moment I’ve been thinking about regarding Beyoncé’s star image comes late in the film, when the diva has gathered a group of dynamic Black women to the moss-covered groves of a southern estate. Sitting alongside Beyoncé on the porch steps are the musical group Ibeyi, Amandla Stenberg, Zendaya, and Chloe x Halle. It’s touching, even glorious, to witness.

When Lemonade was released, it was hailed as a “revolutionary work of Black feminism,” further establishing the idea of Beyoncé as a political figure. But it’s most powerful as a work that charts the artist’s interior life, which should not automatically render a work feminist. The most striking thing about this particular image is not its feminism, but its representational power. Because the world is so starved for deeper portrayals of Black women, many of Beyoncé’s most lasting images have been significant because of who they show. They become surfaces onto which we can graft political ideas. Images like this are potent not for what Beyoncé is saying but for what our projections upon her work say about us as an audience.

2016: Cautious Revolutionary

“Formation”

Music video

You can’t understand Beyoncé without taking into account her identity as a Black southern woman. “Formation” is an impressive turn in her career because of how it locates this self-identification more fully than anything she did before. It weaves in the flavor and dynamism of New Orleans to tell its story — the ecstasy of the Black church, the dynamics of Black cowboys, the glory of iconoclastic Black girls with brightly colored hair demonstrating trends long before the white world takes notice. It grounds itself in a specific cultural context that much of her other imagery lacks.

The most enduring image in “Formation” is Beyoncé on top of a cop car that slowly slides into the water surrounding it. This moment bristles with a newly radical agenda that calls out the problems with the American police state, which targets and snuffs out Black lives. The video got blowback in certain circles for being “anti-police,” and Beyoncé responded in a bare-bones, highly controlled interview with Elle, saying, “I’m an artist, and I think the most powerful art is usually misunderstood. But anyone who perceives my message as anti-police is completely mistaken. I have so much admiration and respect for officers and the families of officers who sacrifice themselves to keep us safe. But let’s be clear: I am against police brutality and injustice. Those are two separate things.” There’s a sense that she’s hedging her bets in this statement, trying not to offend and ending up inadvertently undercutting whatever revolutionary value can be found in the video. No matter. What has become emblematic of Beyoncé’s politics is not her words but the power behind this image.

2017: Matriarch

Pregnant Beyoncé

Beyoncé’s Instagram

Every celebrity engages in a dance between the desire for privacy and the need for attention. Over the years, Beyoncé has increasingly centered her family in her work — especially her daughter Blue Ivy. In February 2017, she released a photo of herself on Instagram, surrounded by lush flowers, to announce her pregnancy with twins. What is she trying to communicate with such images? I think the answer returns to the consideration of power. It speaks to the ways Beyoncé has demonstrated that she’s in a class of her own, framing herself as both a divine mother and the head of a dynasty. That last point is evident in videos like the one for Jay-Z’s “Family Feud,” directed by Ava DuVernay with a star-studded cast, from his 4:44 album. The video tells a futuristic story about a great familial lineage, which it suggests is composed of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s offspring, including an older Blue Ivy as an important “founding mother” who has a hand in revising the Constitution in 2050. It’s a doozy, but what’s important is how these images return the idea of a powerful lineage in the making.

2017: Goddess

“Love Drought” and “Sandcastles”

Grammy Awards performance

At the 2017 Grammys, Beyoncé performed two songs in golden regalia. She is glowing and luminous, as video projections display three generations of Knowles women: her mother, Tina; her daughter, Blue Ivy; and herself. These images of women with crisp halos crowning their heads speaks to Beyoncé’s interest in matriarchal lineage. The use of yellow and gold has been noted as referring to the Yoruba goddess Oshun, while the crown atop Beyoncé’s head echoes the Virgin Mary’s. This is an early example of how the star has pushed her brand in a curious new direction by incorporating imagery that equates Africa with nobility, thereby giving heft to the idea of legacy that her brand of Blackness is based upon. By coupling African imagery with that of her family, Beyoncé positions her lineage as royal.

2020: Royalty

“Already”

Music video from Black Is King

“You can’t wear a crown with your head down,” a voice intones in the trailer for Black Is King, which furthers Beyoncé’s partnership with Disney after her turn in the remake of The Lion King. This line speaks to the ethos of the current state of her career. Her recent work gestures at the idea that, before slavery, Black men and women were African kings and queens who were stripped not only of their culture but their nobility. The lavish and obsessive detail Beyoncé uses to frame her family as a Black dynasty suggests that this is her micro-view of what reparations should look like: reclaiming an idealized past for Black Americans. Visuals in Black Is King highlight this complicated truth: Beyoncé dressed in a bejeweled aqua outfit with matching African headgear, surrounded by black men in the ecstasy of dance. It’s the type of unspecific imagery that doesn’t communicate much beyond prestige, flattening the dynamic nature of an entire continent and its histories and tying the humanity of Black folks to this perceived past nobility. It’s a conservative framing of Blackness, in which wealth and power is tantamount to worth.

*A version of this article appears in the August 3, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!