One of the best new TV shows I’ve seen lately is the Netflix adaptation of the beloved YA book series The Baby-Sitters Club. I like the show for lots of reasons, but chief among them is how genuine it is about the things that matter to its group of young protagonists. Creating a show like that — one that can confidently deliver a warm, sincere, thoughtful tone without coming off as simplistic or self-congratulatory, that will appeal to multiple age groups, and that can pull off a “girl’s first period” plot without feeling gross or pedagogical — is impressive. It takes skill. It’s an excellent season of TV.

There’s a different version of that first sentence, one I might have written if I were reviewing The Baby-Sitters Club even a few years ago. Rather than best, I would likely have swapped in the word favorite. It’s a small but meaningful distinction. Best is always a bit of a lie in criticism, a way to pretend a critic’s subjectivity can be removed from the equation, but it is an important signifier nonetheless. It’s an indicator of quality. The term means “I think this is good, not just for me but objectively for lots of people.” Favorite may be truer, but it also comes off as a qualification: “I enjoyed this show. Maybe you will too?”

The other differentiator lurking inside the best-versus-favorite distinction has to do with pleasure. The best of something may be challenging or hard to watch. It is a signal of artistic achievement — most important, most valuable, most impressive, most serious. Favorite comes with the implicit acknowledgment of enjoyment. It means that consuming something was a gratifying experience. When compared with best, favorite is simultaneously more delightful and less prestigious.

Right now, I’m happy to call The Baby-Sitters Club among the best TV I’ve seen this year, together with a cohort of wildly diverging other visions of best: the teen rom-com Never Have I Ever, a goofy vampire comedy called What We Do in the Shadows, and the off-the-wall, occasionally surrealist political series The Good Fight. There’s been a shift for me and many other TV watchers, a newfound appreciation of a quality I did not value in the same way before. As much as anything else, the appeal of The Baby-Sitters Club lies in how unabashedly comforting it is. The subject matter is a part of that equation, but its capacity to please is also born out of the way the show is built. It is generous storytelling, undemanding and straightforward.

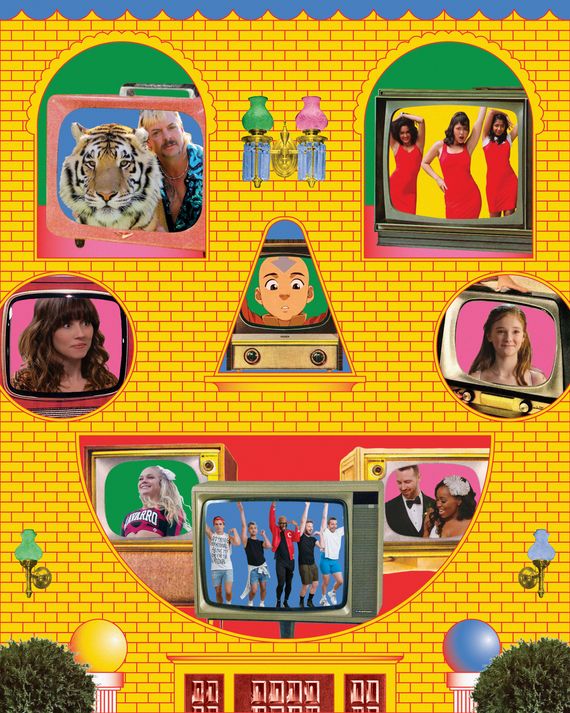

In the past several months, with the terror of a global pandemic sending anxiety sky high and rendering TV one of the few safe entertainment outlets, the desire for comfort has become particularly noticeable. The shows dominating the cultural conversation this spring and early summer have not been ones that fit within the narrow band of prestige television, like HBO’s grim-dark literary adaptation I Know This Much Is True or the slow-moving Damien Chazelle jazz drama The Eddy. They have been the 15-year-old animated show Avatar: The Last Airbender, recently made available to stream on Netflix; the lurid, jaw-dropping docuseries Tiger King; the romantic reality show Love Is Blind; the comedy Insecure; and the Western family drama Yellowstone, which is peak comfort TV for straight white dads and had unbelievable viewership even before everyone had to stay home.

Coronavirus and political anxiety have accelerated this shift toward comfort TV. Who wants to be frustrated or made more sad by their entertainment when the outside world itself feels like a sufficiently brutal place? But the trend was already well under way in television, a result of several simultaneous forces: the Peak TV deluge, the dominance of Netflix, prestige-TV exhaustion, Trump-era exhaustion, a more diverse slate of TV creators, and the streaming-era ability to spend hours revisiting old standbys rather than finding the energy for something new. All those things combined have brought us to this moment, this embrace of the comforting and the undemanding.

At the same time, there’s the growing awareness that comforting, undemanding TV can be worthy of critical acclaim. I am newly confident in the idea that the categories of “favorite” and “best” can be collapsed into each other, carrying all of the favorite-implied ideas of pleasure, subjectivity, and enchantment into the definitions of greatness. Not all comfort TV is great, by any means, but neither was all of prestige TV. The difference now is that accessibility and cheerfulness do not instantly render a show less important. The desire for TV shows that foreground delight rather than despair is not a form of weakness. TV that makes us sad is not inherently better. The pandemic was the final death knell of “prestige” as a meaningful indicator of anything at all, and I’m glad to see it go.

Prestige TV has always been difficult to categorize, in part because it is a mirage. Its gradual dissolution over the past several years is equally tricky to nail to any specific benchmark. But since the fever pitch of critical excitement over shows like Mad Men, The Wire, and the early days of Game of Thrones, prestige TV as an aesthetic has persisted, even while prestige as a reliable indicator of exciting TV you must talk about has undeniably waned.

In 2013, Vulture published “The 13 Rules for Creating a Prestige TV Drama,” a full-feature list that began with installing a middle-aged anti-hero at the end of some major cultural era, making him great at his job and bad at his family, providing a healthy dose of both sex and violence, and sprinkling in a smattering of highfalutin cultural references to make sure the audience could recognize the show’s pedigree and intelligence. I wrote an updated version of that list in 2017 reflecting the way prestige has become as much about how we talk about the genre as the genre itself. In 2015, as a bouncing-off point to define a genre he called “mid-reputable TV,” the critic Noel Murray laid out some “hallmarks of a prestige drama — heavy themes, high production values, accomplished actors,” before conceding that “prestige is a state of mind.” Much of its definition comes from a show’s reception, Murray concluded. “Prestige television is often subject to intense scrutiny, with fans and critics evaluating every plot twist, stylistic choice, and coded method (in terms of both literary symbolism and the show’s attitudes about gender, race, and politics).” In an essay titled “How TV Became Respectable Without Getting Better,” Matthew Christman offers a compelling definition: “Mostly crime. Mostly male. Mostly extravagantly unlikable anti-heroes whose sheer awfulness makes us feel better about our own, more mundane foibles.”

The term prestige entered common use in TV criticism around 2012, when it began to supplant an already fraught discussion about “quality TV.” Janet McCabe and Kim Akass’s collection of essays called Quality TV was published in 2007, and by 2010, I had attended an academic conference where an entire panel was devoted to the definition and dismantling of quality TV as a term. My primary memory of that conference was that everyone spent the weekend talking about Mad Men while doggedly pointing out that surely someone should be talking about some of the actual most-watched shows on TV: Big Bang Theory and Two and a Half Men. No one ever seemed to be volunteering for the job.

I suspect some of the reason for quality TV’s decline and prestige TV’s simultaneous rise is that prestige, as a term, neatly dodges the best-versus-favorite problem. Rather than define television by the pretense of objective greatness, the word prestige, with its snobbish implications, was indicative of a perhaps unintentional truth about these shows. It is a classist assessment, one that implies inaccessibility, scarcity, but also widespread influence and importance. It’s not easy or fluffy or fun because, somewhere deep in the American psyche, there’s still a puritanical belief that fun things cannot also be serious. Prestige TV is demanding, something that creates a further classist implication about its audience. It imagines itself being viewed by educated, wealthy people with enough leisure hours to devote to epic run times and slow-burning, byzantine plots (it imagines this regardless of who may actually be watching). It’s not a coincidence that the outlets that defined prestige TV are also the ones, like HBO, that historically required an expensive monthly premium-cable package.

To the extent that there ever was any such thing as prestige, it surged to prominence in the brief period between the premiere of Mad Men in 2007 and the turn of the decade — a time when Salman Rushdie could declare that TV was the new literature and still have it feel like a bold, newish statement. The beginning of the end came in 2013, when Netflix released House of Cards. That show was an attempt to design the streaming service’s original programming in the prestige model, to validate it as impressive and worth paying for. Several things happened instead. Prestige TV’s original definition (shows featuring sad, middle-aged white male protagonists) expanded a bit, creating space for comedies like Girls and Transparent and dramas with prominent female characters like The Handmaid’s Tale and Westworld. But at the same time, the aesthetics of prestige became very easy to mimic, and as underwhelming copycats popped up all over premium cable, its value as an indicator for greatness began to sink. What once felt like a bold departure from network TV became familiar and wearisome, especially as it collided with the Netflix imperative for more — longer run times, many seasons, constantly premiering new shows. Prestige began to feel like homework, and the prestige-signaling phrase “It’s more of a ten-hour movie!” started to sound like a test of endurance.

The other change was that Netflix quickly branched out into every other kind of TV—talk shows, comedies, horror series, historical dramas. As the service powered the surge in new programming, other streaming platforms and, eventually, prestige outlets followed; HBO adopted the entertainment-in-bulk model with HBO Max, and premium networks like FX were absorbed under the Disney umbrella. If prestige TV was a thin, fragile edifice on top of the mass of TV-programming history, Peak TV was the rush of programming that wore it away — less like a statue being tumbled and more like inexorable erosion.

It’s not that prestige TV has disappeared or completely lost the ability to capture awards or audience attention. It’s not even that great TV shows aren’t still being made in the prestige model. But it has lost the presumption that, because of its aesthetic and the imagined elitism of its consumers, it is immediately more valuable or significant. It has become one mode of TV among many. The era of its dominance is over because the idea that one kind of TV is intrinsically, objectively better is waning. Better for whom?, a viewer today might ask.

The idea that it’s fundamentally suspect to take pleasure in entertainment is an old one. It’s certainly as old as Plato, who worried that theater would make people less thoughtful, and it continues through the history of literature, especially with the rise of the Evangelical novel in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. In graduate school, I read Coelebs in Search of a Wife, by Hannah More, a book that was wildly popular in its time and also unimaginably boring. More believed it was a sin to experience pleasure while reading fiction; the aim of her novel was to be more worthy precisely by being so stultifying. In her thinking, to experience pleasure through entertainment is base. Sitting through a long, boring book on an important topic — that makes you a better person.

I thought of More while I watched one of the most popular, talked-about shows on Netflix this month, Floor Is Lava. The name succinctly summarizes the premise: There’s a room full of objects; the floor is flooded with a bubbling, sloshing, slippery red liquid; and teams of people have to navigate their way across the room without falling in. Usually they fall in. It has the same essential appeal as a 30-second video of a guy getting hit in the balls. Floor Is Lava is not edifying, and it’s not an especially excellent TV show. It’s not trying to be. But it does succeed at exactly what it sets out to do.

The same could be said for any number of the most popular series of the past year, especially some of the reality shows, including more artful ones like Netflix’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up and Salt Fat Acid Heat. They’re soothing, first and foremost, lovely to look at, and deeply reassuring. Many of the new shows are excellent — Never Have I Ever is both thoughtful and intricately crafted, a romantic comedy that highlights an Indian-American teen’s experience and is also a delicate depiction of grief and familial love. But at a time when so many TV viewers need to be soothed, value propositions change. Excellence is also judged by the capacity to calm and gratify.

The age of Peak TV has produced more content than any one person could ever watch in a lifetime; comfort TV likewise exists in too many disparate genres and styles to assign it any one distinctive formal footprint. But what these shows share most is a total rejection of the idea that it’s better to have to wait for the good part. Front-loading pleasure can mean different things. Comfort shows are often faster paced, brightly colored, and repetitive; they’re united, though, in the way they disdain hidden meanings and emphasize clarity and immediacy over abstraction. If the classic truism of prestige TV is that you have to hang on until the show gets good by episode seven, comfort TV has no interest in confusing its audience or wasting time.

Because of the shows themselves — their avoidance of complicated puzzle-box structures, their often more straightforward storytelling — the conversation about comfort shows is also distinct from the critical modes of processing television. If prestige criticism was often focused on dissecting every plot point, the conversation around comfort TV is less evaluative and more prescriptive. It’s the “This silly show is actually quite good!” mode, the era of “If you liked X, you might like Y.” Where prestige was often driven by critics guiding viewers to the best programming, comfort TV inverts the order. Much of the most interesting writing about Tiger King wasn’t produced to get people to watch it; it was written because so many people already had.

It’s worth noting that most of the comfort shows that have leaped to the status of undeniable prominence, the ones that suddenly everyone seems to be watching, are on Netflix, which has managed to cross the Rubicon of TV subscription services, moving from its original status as an optional add-on to something closer to a standard household utility. Some elements of comfort television, too, feel like a return to a much older era. There has always been accessible TV on major networks and premium outlets, and just as Emily Nussbaum famously argued for the cultural importance of Sex and the City in 2013, there have always been critical voices arguing against the prevailing wisdom that those shows were frivolous. The idea that TV should be direct and immediate, that its storytelling should pony up the goods in every episode, that it should above all invite rather than perplex — that is the ethos that drove much of TV in its earliest days. Comfort TV in the past two years looks not unlike This Is Your Life, Leave It to Beaver, or The French Chef. Yes, some shows of the 1950s and ’60s were about as deft and nuanced as a falling anvil, but, in the case of the greatest TV of that time, they were able to embrace generosity without sacrificing intelligence or artfulness.

In the ’60s, though, TV was still widely considered the idiot box. The difference now is that TV has been yanked upward in the cultural hierarchy through the prestige-era bids for seriousness. The new wave of comfort television is a pendulum swing, a corrective to prestige and a return to the past. I am grateful that this time around, it is more diverse and slightly more keyed to the comfort of many people rather than an imaginary straight, white default. Its success also cannot be untangled from its present, from the looming global awareness of our need to be comforted. Part of its legacy will be its role as a reaction to the dark, dreaded weight of the TV dramas that came before. But it will also be that, for a time, the world got too dark to bear those dark stories, and there was greatness in being delighted.

*This article appears in the July 6, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!