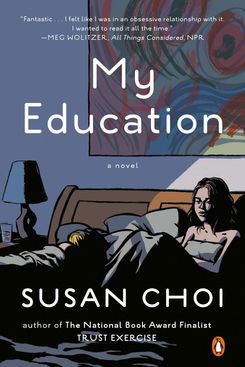

For her debut novel, Luster, Raven Leilani wanted to write a Black woman who was “pure id.” Her protagonist, Edie, a 23-year-old art-school dropout who is fired from her publishing gig for having sex on the job, thirsts after an older white man she meets online — not despite the power differential between them but because of it. The sex scenes Leilani crafts are violent, debasing, and fluid, the engine of the book’s plot and of Edie’s eventual self-revelation. For those scenes and the novel itself, she found inspiration in Susan Choi’s My Education.

I would have liked a single rope to bind us together, with tightly stacked coils, so that we formed a sort of Siamese mummy within which our two bodies got mashed into one — and having fought me to half an arm’s length so she could undo my jeans, and peel them off with a hard downward step of her deft pointed foot, she simply seized me by the armpits and heaved me away from her onto the bed, and as I struggled to regain her kiss pinned me flat with the heel of her hand so that she could, when I gave up the struggle, with a leisurely sigh sink her face in my cunt. I seemed to come right away, with a hard, popping effervescence, as if her mouth had raised blisters, or an uppermost froth; but beneath, magma still heaved and groaned and was yearning to fling itself into the air. Until now, my orgasms had been deep and ponderous things; slow to yield to excavation; self-annihilating when they finally did, so that in their wake I felt voided and calm, every yen neutralized, and gazed on whoever had managed the work with benign noninterest. Never had there been this tormenting, self-heightening pleasure, like a hail of hot stones, and yet she seemed to recognize just what had happened, so that before I had even stopped keening she bore down again. She made me come so many times that afternoon that had I been somewhat older, I might have dropped dead. Had I been a doll, she might have twisted off each of my limbs, and sucked the knobs until they glistened, and drilled her tongue into each of the holes. Certainly had the windows been open, as would have made sense on that sunny June day, my thundering cries, in the end, would have summoned the neighbors; for Martha, in dismantling me, dredged a voice out of me I did not know I owned; the devastation of my pleasure surged outward and outward again, like an ocean-floor tremor, while that voice I had never imagined was bellowing harshly Oh GOD, Oh GOD, OHGODOHGOD!

The kind of book I’m looking for tends to have obsession at its core. When we begin My Education, we’re introduced to the protagonist Regina’s desire through the figure of her professor, this problematic and seductive person she becomes enamored with. That’s where we start. Where we end is with the professor’s wife, Martha. My book basically does the same thing. There’s something deeply off limits about that arrangement — a subversion of the reader’s expectation.

There’s not quite a hundred pages before you get to this passage. Choi is so precise in how she choreographs the buildup. As Regina meets the professor and starts to fall under his spell, every now and then there’s an interaction with Martha. There’s a silent recognition but also a real barrier to their communication. I often frame the erotic in terms of denial. On the craft level, there’s a beautiful delaying of gratification, which is so important to good sex writing.

There’s violence all throughout this passage — the sex is a torment, a hail of hot stones. There’s a speed and a weight and a real physicality to it. Not just the word choice but how it’s arranged. There’s a speed to the rhythm of the sentences that intensifies the violence. It’s not just the image of drowning, the idea of being totally out of control, but the way those images are pressed right up against survival. It works partly because a more traditional way to talk about two women coming together is for the language to be soft, maybe even maternal.

When I write sex, I refuse to pan away to the curtains. It is important to me to show, as Susan Choi does here, the moments that are, traditionally at least, unsexy. The blisters. The mummy — that’s a death image. But part of great sex writing is the inclination to talk about the blisters and the mummy.

There’s a beautiful use of hyperbole throughout. There’s florid academic language, and there’s also the really frank language of “her face in my cunt.” That’s a beautiful whiplash. Like, She’s going all caps! I love that commitment.

I’m drawn to the ecstasy of emptiness, of being emptied and exhausted and dissected and torn apart — Regina as a doll, Martha sucking the joints. The imagery of emptiness and the imagery of being made new. There’s a clear power dynamic here, and it’s unbalanced; in Luster, I tried to write toward that imbalance too.

In starting to talk about my book, I’ve found it challenging to articulate the dynamics of my protagonist Edie’s desires. I think this is because of Edie’s identity — there’s something more fraught about what it means, as a Black woman, to invite a subjugation. It’s so tricky to talk about because there’s a fair conversation to be had about what it means to inflict violence into the body of a Black woman. Because we do live in a culture that is indifferent, specifically, to Black women’s pain and their softness. But If I’m honest, when I’m actually writing, I’m not thinking about the political ramifications of what I’m writing. I’m thinking about what feels good and what feels true. More than anything, when I sat down to write, I wanted to write a Black woman being led around by id. I haven’t found many portrayals of Black women like that in literature. I wanted to see the freedom of that on the page.

*This article appears in the August 3, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!