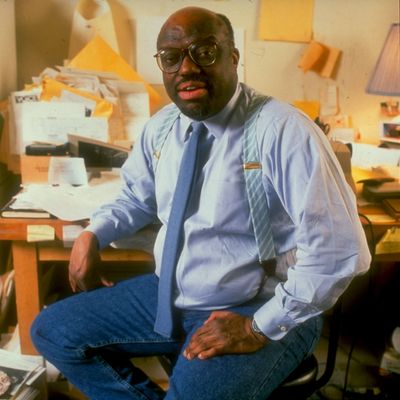

Stanley Crouch, the critic and author who died this week at 74 after battling an unspecified illness, filled many roles during his long, cantankerous career. He was a drummer dabbling in the avant-garde before scaling back to become one of the most traditionalist voices in jazz, dismissing the many counter-revolutions that came after bop. He was a fundraiser for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and a Black nationalist who later condemned Spike Lee for “doing the race thing,” and wound up advocating a bootstraps mentality for Black Americans that played down the “determinism” of systemic racism. He was a widely published and beloved author who literally sparred with his detractors: He once slapped the author Dale Peck for a scathing review of his first novel, and was fired by The Village Voice after getting into a fistfight with a colleague.

“If you’re going to get in the ring and try to take the belt, you have to prepare to get hit,” he once said, stepping perhaps beyond the level of metaphor.

The through line here, of this shining example of the contradictory self, was Crouch’s undying advocacy for jazz — for its place at the heart of the American experience and in the country’s art institutions. In his lyrical prose, including his masterful 2013 biography of Charlie Parker, Crouch centered the idea that “the jazz band put democracy into aesthetic action,” while rebuking white critics whom he saw as overstating the role of white musicians in a Black art. And in 1987, the critic, together with his friend and fellow purist Wynton Marsalis, was named to a committee that led eventually to the founding of Jazz at Lincoln Center, the most prominent organization in jazz. For his singular career, he was awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant and the title of NEA Jazz Master, the highest honor in the music form.

To help grapple with Crouch’s tangled legacy, New York spoke with playwright and director George C. Wolfe, who was Crouch’s student at Pomona College in the 1970s. (Crouch, a college dropout, began teaching drama there in his 20s.) Wolfe, who directed (among many other things) the first run of Angels in America on Broadway and previously served as the artistic director of the Public Theater, spoke on his teacher’s combative nature and the “thoughtfulness” that underlaid his more abrasive moments.

What was Stanley like as a mentor?

I knew Stanley when I was very young and he was a bit older, and in some weird way he felt protective of me and proud of me. That felt very important, because he was so stunningly smart to me when I first met him. And seeing how smart and flawed he was was liberating to me.

I directed him in a play in Pomona, The Fabulous Miss Marie. He was the husband of Miss Marie. All students and him. And when I first moved to New York at 24 or 25, he was one of the first people that I reached out to and hung out with. One piece of advice he gave me then was, “In New York, they can’t hit a moving target. So keep evolving and keep doing as many different things as you want to.” When I was at the Public Theater, he said, “Don’t ever leave that job — you have a power base.”

You meet people when you’re young and confident who affirm this idea that you have about yourself. They help you believe it. He believed in my talents before I fully believed, and there was a part of me that trusted and listened to him. And when he was saying something that was full of shit, I didn’t ever allow that to discredit the thoughtfulness.

It seemed like he took his moving-target advice to heart, considering the changes in his approach to jazz.

The thing which was always fascinating to me about Stanley was that there was this incredible degree of thoughtfulness that was frequently overwhelmed by a kind of audacity. A dynamic that can exist in New York is that the cult of personality can overshadow the substance. And I think he was very substantive and thoughtful and thorough in his examinations of a culture, a story, or an idea. Even if you didn’t agree with him, there was an incredible thoughtfulness that was going on. That’s what I connected to. There’s him rubbing his face and this kind of intense aggression, but I didn’t listen to the aggression, I listened to the thoughtfulness.

Did you ever get into an argument with him? That seems like an interesting experience, considering his work history.

When The Colored Museum was first at the Public Theater, Stanley came to see it and we ended up discussing someone else’s work that was creating a sensation at that exact same time, which he celebrated instead of my material. I didn’t consider this other work to be on the same exact level as mine. It sort of wounded me, but I got over it very quickly. That was really fascinating to me. But I was never on the receiving end of any of his brutality.

In addition to his shift from playing in the avant-garde to becoming a major advocate of traditional jazz, he also shifted from a Black nationalist perspective to condemning artists including Spike Lee and Toni Morrison for their presentation of Blackness in their work. As a creator and someone who knew him, how do you interpret some of his more controversial criticism?

That’s one of the things, you go, “No, no, you’re saying that about Toni Morrison? We’re not interested in that.” Do you know what I mean? “That’s your opinion. No.” I’m sure for him there was a thoughtful basis, but there was a degree of sensationalism to it.

In a moment in which there is a national focus on the systemic causes of racism, how do you think his more individualist, and arguably more conservative, critiques on race reverberate?

I think you are the time that you were born. You are the circumstances that you existed in and that’s how you see yourself in regard to race and culture. You can’t separate who he evolved into from who he was and what he overcame. I think he was 22 when he began teaching at Pomona — that’s an astonishing accomplishment. The details of one’s story leads one to their political and cultural beliefs. They’re not abstract, they’re incredibly intimate. His approach became: “I did it, I can do it, everybody else should be able to.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.