We’re back in, everybody. Well, not “in” in — most productions still only exist online. We don’t exactly know which shows are going to stream when this fall: announcements are rolling out slowly, and even at theaters that are sure something will premiere, dates past the next three weeks are hard to come by. But the (sad) funfair vibe of the first six months of shutdown has passed, and September brings a datebook with plans actually inside it; a budget for tickets, since few of the digital offerings are free anymore; and the old buzzsaw of judgment, cutting away at what seems slack or underthought or dull. It’s sort of like starting a season.

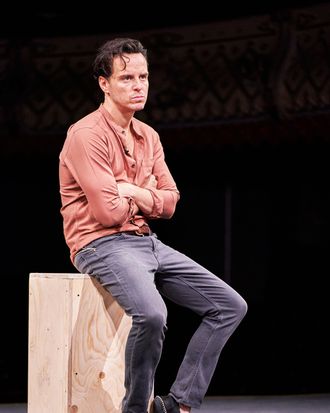

The first show of my fall season was Three Kings starring Andrew Scott, an online production in London’s Old Vic in Camera series. Shot inside the theater itself, the short-run, star-filled live videos are setting a visual standard that so far the U.S. theater hasn’t been allowed to meet. (The show before Three Kings was Lungs with Matt Smith and Claire Foy; the show after it will be Brian Friel’s Faith Healer with Michael Sheen.) The Old Vic starts from an advantage: Empty, the Old Vic is beautiful, a Escherscape of stacked, melancholy balconies. (In a spooky touch, the presentations start with the piped-in murmuring sounds of a full house and end with a storm of applause.) Each production is a live-editing feat, with a camera team often giving us multiple simultaneous views of an actor, then placing them next to each other like panels in a comic book. In both Lungs and Three Kings, the performers displayed an amphibian facility for both stage and film — you can get close without detecting a false note, but they convey size too, the kind of reach and pitch that the theater needs.

For someone eager to see similar programming happen in the U.S., the seeming ease of the In Camera productions is … frustrating. London’s safety rules permit shooting inside theaters, but New York’s do not? Or perhaps, six full months into the pandemic, producers and Equity haven’t worked out how theater actors can play sustainably and legally on video? Many theaters here are tangled in a Gordian knot of union rules, making the buildings themselves expensive or even impossible to unlock, let alone use as performance spaces. But I, like hundreds of others all over the world, have bought tickets to the Old Vic productions, proof that people will pay to see short plays, either monologues or socially distanced duets, being shot by multiple cameras and broadcast live. Come on. If we can put a man on the moon, we can get Audra McDonald and a camera crew into Radio City Music Hall.

But what about Three Kings itself? Stephen Beresford wrote the solo play specifically for Scott, who delivers a monologue the way a military-grade crossbow delivers its bolt. (Last weekend’s three-day run of Three Kings is already over, so the closest you can come now to seeing it is to rent a video of Scott performing a different play, Simon Stephens’s Sea Wall, another monodrama about a man baring his sins.) Beresford has himself been an actor, and the monologue swiftly gets us into the “good stuff” for a player — deep rage and tamped-down sorrow. Within minutes, Scott’s character is telling us a story about being 8 years old and meeting his grifter father for the first time. The boy is full of hope and plans, while the aloof father manages to emotionally connect only enough to show him the set-up for a coin trick — the three kings — that will be sure to win him bets in bars. Scott’s jaw clenches as he remembers the innocent child, who grows into a man who still can’t shake his need for approval and love from a serial liar and abandoner. Scott runs his hands through sweaty hair, staring at the camera in desperation and self-loathing. The boy, almost inevitably, turns into someone very like the father. One king becomes the next, as interchangeable as pennies.

The performance is extraordinary, a demonstration of the actor’s charismatic power. In fact, Beresford’s storytelling in Three Kings is very like that of the Stephens monologue — both are confessionals; both are atmospherics rather than dramas. If we catalogued theater purely by emotional impact rather than by pseudostructural terms like comedy, tragedy, etc., these two pieces would sit in the same category. We watch them to drop swiftly into a mood, to be borne over the falls of feeling. They’re like pieces of music. They’re ballads.

It’s not a coincidence that Scott is in both of them — as a performer, he’s got the magnetic qualities of a balladeer. His particular gift, as any fan of the last season of Fleabag will agree, is a kind of immediate, enfolding intensity. Scott’s voice is always on the verge of breaking: He can teeter between self-mockery and vulnerability for a production’s full hour. And it’s interesting that these brief plays are so particularly suited to being broadcast digitally; the attention problems that conventional plays run into online don’t have time to set in. Pandemic-brain has stopped me from reading books in quite the same way I used to, but I have gone back to old favorites, even from high school, just to read the climactic or most heart-wrenching bits. Sea Wall and Three Kings operate like those dog-eared sections — shortcuts to escape.

I do think that when in-person theater resumes, my appetite for this type of character study is going to dwindle again. Onstage at the Public Theater and later on Broadway, Sea Wall (with the superb Tom Sturridge) seemed too slight — a short story in a form built for novels — and the same would probably go for Three Kings if I were to see it at a theater. The film-theater-online hybrid performance does, though, seem to be the ballad-play’s most appropriate platform, so apart from its other pleasures, it was thrilling to see a form find the proper home.

Far less successful was my second fall-season show, In Love and Warcraft, a Zoom production co-produced by the American Conservatory Theater and Perseverance Theatre. Madhuri Shekar’s 2014 romantic comedy, in which a college-age Warcraft super-gamer Evie (Cassandra Hunter) falls for a boy in real life, grinds to a halt almost immediately on the digital stage. Shekar’s particular type of realism needs the detail of a physical production; her comedy relies on interplay; the way she writes flutter-at-first-sight relationships needs IRL chemistry.

The company does demonstrate imagination and invention: director Peter J. Kuo comes up with clever “reasons” for each shot — a Zoom caption at the bottom of each window lets you know if you’re peering through a webcam as Evie plays Warcraft, or eavesdropping through a friend’s smartphone left on a table among the glasses. The live editing is impressive, so characters appear to chat and flirt and even kiss, simply by moving to the extreme edges of their screens. Yet Shekar’s dramaturgical timesense is fundamentally theatrical rather than virtual, meaning scenes seem overlong, even if they would have played gracefully onstage. Occasionally I could sense the sweetness of Shekar’s original, which floats ideas of Evie’s potential asexuality around inside the college comedy — a real issue, buoyant in the froth. But despite Kuo’s skill and the actors’ light touch, it collapses.

You can watch the live In Love and Warcraft with the chat window open, which can be quite charming — several of those watching the night I did were clearly Warcraft aficionados, and Shekar’s nerd-cred stayed strong throughout the evening. (Further live performances are on September 11 and 12; after that, there will be on-demand video sales through the 25th.) Clearly the aesthetics and emotional dramaturgy of video-game play is something that theater should continue to explore. In fact, after my disappointment with In Love and Warcraft, I found myself drifting to another online performer, the hypnotic Shirley Curry, also known as Skyrim Grandma. For years, the beloved Curry has been wandering through the video game Skyrim, in which a player investigates a detailed fantasy world, looking for quests and amassing mythical powers. Instead of playing to “win,” Curry comments gently on what she finds, tries to avoid trouble, and (politely) declines swigs of mead. Her videos are extremely theatrical: As you do at a show, you lose yourself in watching someone else play, you live vicariously, you let the stage’s rhythms dictate your own. And as a mood piece, it’s a balm. Curry’s unflappable, and the terrors of the game (dragons, bandits, touchy skeletons) all subside in the face of her calm inquisitiveness. Hmm, she and we wonder as a bandit gets an arrow in the throat, where to go next? I hope a playwright works out how to capture this particular emotional and dramaturgical effect in a play. God knows I want to watch that show. I need to spend a little more time being both curious and unafraid.

Love and Warcraft is streaming through September 25.

More From This Series

- Launching Into Adulthood, With Frenemies and Hummus: All Nighter

- Where’s Willy? Abe Koogler’s Deep Blue Sound

- Sumo Is a Subculture Story That Goes Big