Glen Keane is a literal Disney Legend; he was given that official distinction in 2012 by the studio, where he spent nearly four decades as an animator. Over the course of his career, he was responsible for animating characters like Ariel from The Little Mermaid, Beast from Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, Pocahontas, and Tarzan. But he’s only just gotten around to directing his first feature: Netflix’s gorgeous, surreal animated musical Over the Moon, which opens this week, about a young girl building a rocket so she can meet Chang’e, the Chinese goddess of the moon. (It’s his first feature, but not his first directing credit: After leaving Disney, Keane won a Best Animated Short Oscar for the late Kobe Bryant’s Dear Basketball.) Here, we talk about his career at Disney, the challenges of directing, what it takes to animate a face, working with Kobe, and Over the Moon’s journey to the screen.

You’ve had a long, storied career in animation. But Over the Moon is the first feature you’ve directed. Were you prepared for all the challenges?

Well, I was trained by Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men, who referred to themselves as directing animators because they would take sections of the film and design characters, work with the voice talent, do storyboarding and layout. That’s the way I was taught. Everything that I’ve done, I approach it from sequences. So I knew how to get the most out of a character in a certain moment in the film. What I didn’t have was the map: I didn’t have getting from beginning to end. That was the director. I didn’t have to worry about it. I just dove in and lived in the skin of the character. On Over the Moon, the map I had was a phenomenal one from [screenwriter] Audrey Wells. That gave me an enormous amount of confidence.

How did the screenplay for Over the Moon come to be?

The idea really started with producer Janet Yang, at the Pearl Studio in Shanghai. She had developed this idea based on the Chang’e goddess, who is better known in China than Santa Claus is here. The kernel of the story was this idea of a 12-year-old girl building a rocket to the moon to meet the goddess on the dark side of the moon. They handed that off to Audrey Wells, who really poured her heart and soul into this film. More than a story or a piece of entertainment, it was truly a message to those who would be left behind; Audrey [who died in 2018] knew that she would not live to see the end of this project.

I gave this talk at Annecy [International Animation Festival] in 2017. I was presenting Dear Basketball, but I was really talking about everything I love in animation. I called the talk “Thinking Like a Child,” about the idea that children have this ability to make themselves believe. I love characters that believe the impossible is possible. Both Melissa Cobb and Peilin Chou were in the audience; Melissa would become the head of Netflix and Peilin was the head of Pearl. They both just said, “That guy has to direct this movie.”

You’re something of an outsider, coming in to make a film about an Asian myth. What did that require on your part?

It was very important to have the guidance of this team around me. I have a producer in Gennie Rim, who has this amazing skill of team building, of bringing people around you to really fill in the gaps. This was not a film told from an American looking at a Chinese story and telling it to the world. I was invited in. So you go into it with respect and [are] open to learn. For example, there’s a moment where Fei Fei is given a gift from Mrs. Zhong, a woman she cannot stand. And I knew how a 12-year-old American girl would take that gift. There would be no way that she wouldn’t give some clue [of] I’ll take it, but I don’t like you much. There’d be some way of communicating that. So I talked to the artists in China and they said, “Oh, no, no. The respect of generation — somebody older — is so deep, you would never give that anything other than respect. It would be sincere and pure.” So she takes that [gift] and we animate it, and she bows very deeply. I said, “So what do you guys think?” And they said, “No, no. That’s not right. She wouldn’t do that.” I said, “Well, what? I thought I was doing it well.” They said, “Yeah. Well, no, that’s the way an older person would bow, but Fei Fei’s 12 years old […] A new generation, it’s a very subtle little bow.” So we went back and redid it. So there’s a lot of fine-tuning. Of course afterward, Fei Fei, you see her in her room, and she slams the door, and you see all of those emotions come through.

Disney is famous for its process of working on a film for years and revising it and revising it — everyone coming in, being highly critical, and sometimes overhauling everything. Is that the kind of situation in which you thrive? Was that something you tried to create in this process?

No. [Laughs.]

Feel free to be as frank as possible.

I naturally am a very collaborative person. I open the floor to everybody, from the production coordinator to the person who takes care of the trash to our head of story. I mean, I just really, really want to know how this is going. You’ve got to direct with an open hand, saying, “Help me.”

When Melissa Cobb of Netflix came into our little studio there in West Hollywood, we had just finished Dear Basketball. We have this little Spanish-style house, and, in the living room, was a table where Kobe [Bryant] and John Williams had sat when we were working together. And now Melissa Cobb is sitting in their spot, and she’s got this spark in her eyes, and she’s talking about what she hopes Netflix can be as an animation studio, and that we would be the first ones to land there. As she talked about creative freedom, it was clear that the success of Netflix was going to be How true can you be to who you are? I said, “This is really wonderful, but is it true? Is that really going to happen?” Because there’s always the point in a film where you think, It all seemed so clear in the script. Why do I feel lost now?

And, of course, on Over the Moon, that moment happened as well. A story-guru executive came in, and I sat for a good hour with her. She had said to Melissa, “Well, I’m going to blow up this film.” So she proceeded to tell me why this movie would not work. And somewhere in there I realized, Oh, this is when the movie changes directors. This is that fork in the road. And I really believe the path that I’m going. I mean, it’s foggy, but I really do know which direction is north here, and I’m facing that way and the advice is to turn around. At the end of that, I said to her, “Hey, I really appreciate this, but the movie you’re describing is not the movie that I want to make. I like the movie that I’m making.” Melissa Cobb afterward said, “Well, that went well.” I said, “It did?” She said, “You are stronger than ever that this is the path you want to go. That’s exactly what we need.” That was so refreshing.

Give me an example of a suggestion that came from an unlikely source that you embraced for the film.

In our screenings of Over the Moon, I invited people of every point of view on our team, including support staff — even our parking attendant — and I would ask their thoughts. I have always done this in my work. I know how much creativity is a gift and by God’s grace it can come through anyone at any time. I don’t want to limit ideas. At the very end of the movie there is a scene where Fei Fei looks at her scarf and then up into the night sky and remembers her mother. There used to be dialogue at this point of Fei Fei talking to her mom. It was a very beautiful moment. After the screening, as we all sat in the theater, I asked for reactions. Our story team made various comments. Then there was silence, so I asked the young man whose job it was to work out our daily schedule. It was the first movie he had worked on. I guess I put him on the spot, because he nervously looked around, thinking, Me? You want my opinion? Finally, he suggested perhaps that section at the end of the movie could play without dialogue. I had storyboarded that section, and it would mean me throwing out some of the drawings I had done. I was very proud of those drawings. But the idea of allowing the moment to play in silence was a more powerful way of allowing the audience to live in Fei Fei’s mind.

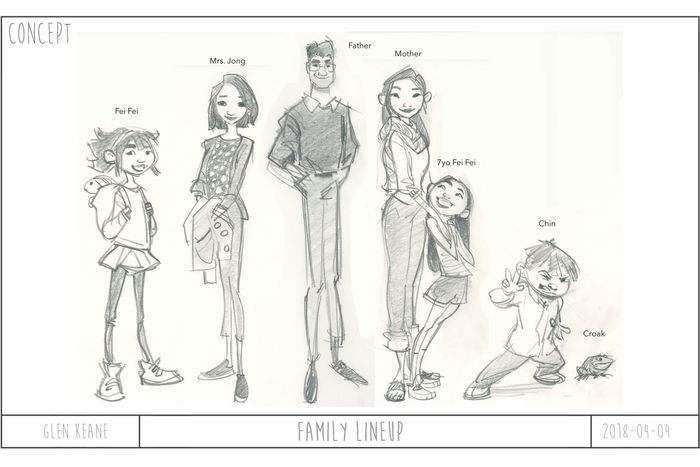

I’m always interested in how expressive animated faces can be, even though the designs might seem simple. The brother character, Chin, is so delightful because his face is just like this simple little sphere, and yet it has such a wide range of emotions. What’s the secret to being able to animate that?

Well, underneath every one of these characters is a skull, and there’s a rib cage, and there’s vertebrae in the neck, even though you don’t see much of it. There’s the cheekbone, an incredibly important part. There are delicate little design elements that are those pinpoint, mote areas that define bone, even in a round face. And those become the points that are solid, and everything else flexes from that. When we’re working with characters like Fei Fei, for example, you’re designing intently for the moments that you know are going to come. This is a girl who’s supersmart, so you’re going to be animating the moment of discovery in her eyes, the moment something clicks. But besides this intelligence there’s also this faith; she can see what others can’t see. So there’s a hope. When I think of hope, it’s the lower eyelids squeezing up. How does that translate in an Asian eye? What happens to that beautiful curve? There’s a double eyelid that takes place there. I was surrounded by Asian women — on this movie we had an incredible female team — so I’m constantly looking at the skin above the eye, looking at what happens in the lower eyelids. When I watch the movie, I watch the corners of Fei Fei’s mouth — because in CG, mouths are pinched, they go to the edge. But if you look in the mirror and you open your mouth, the upper lip rolls into this beautiful little round curve here, and then the lower lip rolls out. So when you smile, there’s a little bit of dark where you see the depths, and those teeth sit in there. It’s so appealing and beautiful. So, you have to have a foundation of that observation, anatomy, and also reading about emotions and expressions. And looking in the mirror. I would practice with my wife. She’d sit across the table, and I’d think, I wonder how small of an expression I can do with my face, with my eyes, that she would see it. So I’d slowly lift my eyelid just a little bit. She’d go, “Why are you making that face?” I was like, “You saw it. You saw it!”

Tell me about working with Kobe Bryant on Dear Basketball.

The strange year 2020 started with the death of Kobe for me, and I think for the world. It was unthinkable. For all of us, we came back into work the next day and gathered together in a circle and shared our thoughts about Kobe, and there was a lot of tears. I was hit with the message of the film — how, in animating that, I had Kobe leaving the basketball court, going into the tunnel, and he was going into the dark, and he was gone. And I had thought, Something’s not right. He can’t go into the dark. So I reanimated it, and he goes walking away, and he goes into the light; it gets brighter and brighter and brighter. And then it just envelops him. I thought [at the time], Wow. I hope Kobe doesn’t mind, but it feels like I’m saying Kobe’s going to heaven here. He’s dying and he’s leaving this world. But I realized how the message of that film was really a wonderful encapsulation of who he was. He was such a gentle, quiet guy. You had to lean in to listen to him as he was talking about the things he loved about that film, and how honest and sincere he was about that.

Was Audrey Wells able to see Over the Moon before she passed away?

We showed her the first screening. And she was able to work with us through bringing in the songs, because it wasn’t a musical at the beginning. I just was reading her words, and I thought, I think Audrey is writing this as a musical; she just didn’t say that. Because it’s all there. And as soon as I mentioned that to her, her eyes lit up. She loved musicals. The last conversation I had with Audrey was a wonderful one in my office a few months before she passed away. We were sitting on my couch and she was facing me with her feet up toward me, because it’s the only way she was comfortable at that point. We were talking about the Wizard of Oz and how that movie was a wonderful model. I was talking about our movie and Fei Fei going to the moon, seeing this goddess, and how it’s very much a dream that she experiences and goes through this healing. And Audrey says, “No, it isn’t. It’s not a dream.” I said, “Okay. What about Dorothy? She goes to Oz. That’s a dream.” “No, it isn’t. No, it wasn’t. Do you think it was?” I said, “Yeah.” She said, “No.” So we had this argument. And I could see in her eyes this childlike faith of No, it’s real. It has to be real. And I decided, man, I am going to hang onto that and we will tell this movie in a way that’s on the razor’s edge, and we’re never going to give it away whether it was real or not. We’re going to let the audience fall one side or the other on that.

I want to talk a little bit about your time at Disney. You were supposed to direct Tangled. How did it change after you left?

We were approaching Rapunzel using a Rembrandt style, where she’s coming out of the dark. There was darkness to the version of the movie that I wanted to make, and that turned out to be not so Disney-like. We had a screening and everybody was like, “I didn’t know we could make that kind of a movie. This is really exciting.” And it really, truly was. But it was pushing the needle away from, maybe, mainstream Disney. I mean, it was a good film. It was so much about this love and healing. It really had so much depth to it. All I can say is that I loved that movie. Then, in the process of changing it — it was very difficult to take something that you love and change it and change it and change it until … Then there was a heart attack that I had. At that point, I stepped off it and just supervised the animation, and that was a pure joy. And Byron [Howard] and Nathan [Greno] came in, and they really delivered a wonderful, fun film. But I felt like I grew in a lot of ways as a director through that. Because I was out there working on it for probably five years before that happened.

So your version of the film was fairly far along. Does it exist in any form anywhere?

It does, on some DVDs that I’ve got spirited away.

Do you think there’s any chance we’d see that version at some point?

I don’t know. I’d have to have you come over, and we’d have some beers, and then I could pull it out. But, no, I have to respect Disney’s choice on that. That’s who they are. It was difficult, but I cherish those days with the studio and will always have that Disney DNA in my heart.

If you had to preserve one memory from your time at Disney, what would it be?

It would have to be within my first week of animating at Disney. I was given a shot to animate in the first Rescuers, just a little thing of Bernard sweeping in the United Nations building. I could not figure out how to do a sweeping action. I thought I was single-handedly going to destroy Disney’s reputation. I was 20 years old. I’d been hearing all along that the key to Disney animation was sincerity — and I’d been sincerely trying to animate. I mean, pencils were constantly breaking. I was hitting people in the head with points flying off my pencil, and everybody was laughing at how hard I was pressing. But I was literally trying to animate with sincerity. Now, next to the bullpen of a group of us trainees was Eric Larson, who was very much a gentleman and a grandfatherly guy. So I went in and knocked at the door. I say, “Eric, I can’t figure out this scene. I’m trying to animate the sweeping action.” And I thought he was going to give me some formula for that kind of an action. But he said, “Well, Glen, what kind of a guy is Bernard?” The little mouse. And I said, “I don’t know. What do you mean?” “Well, does he want to do a good job?” I said, “Well, yeah, I guess.” He said, “Of course he does. That’s the kind of a guy he is. He wants to clean up every speck of dust off the floor, don’t you think? I mean, don’t you think he puts his whole heart and soul into what he’s doing?” And he just started talking about Bernard like he knew who he was. I realized, man, here’s this guy who’s nearly 70 years old and he instantly is in the skin of Bernard, talking about him as if he’s this little guy, with words of endearment. And the sincerity is to believe, like Eric does, in this character. That was the beginning of that whole career for me — believing in the characters that you animate.

You were right there in the middle of things during the Disney Renaissance of the 1980s and 1990s. What was it that allowed that resurgence to happen?

I think the best thing that happened to us was the threat of it all going away. When I got there, you felt like Walt Disney was still there. Frank [Thomas] and Ollie [Johnston] would talk about Walt. There was hardly any time since he had passed away. There was very much this sense of “the way Walt would’ve done it.” When Frank and Ollie retired, there was this floundering time of trying to find our way, and Disney was threatened with being sold. Michael Eisner and Roy Disney came in to regain control of the company. They moved into the animators’ offices and all the animators moved out, boxes of stuff in their hands. We moved into, I believe, a coffin factory in Flower Street in Glendale, with the thought that they didn’t need to keep animation anymore. That felt real. And it was like being forced to move out of home. You’re 18 and you’re out on your own, and you’ve got to go make a living somehow and you’ve got to do it fast.

Ron Clements had written this script, The Little Mermaid. At first Michael had said, “No, we already did Splash. We don’t need that.” But Jeffrey [Katzenberg] thought about it and came back the next day and said, “Oh, I think we should do that.” It was the return of a fairy tale. It was the return of who you are. I mean, when I think of Pixar and Disney films, I feel you can boil it down to this: Disney is ultimately about Once upon a time, and Pixar is Wouldn’t it be cool if? Pretending to be a kid and playing with a toy. So, going back to that fairy tale was life-changing for us. Howard Ashman and Alan Menken coming in and bringing music. Working at the studio, hearing Alan playing (singing), and him getting inspired by the drawings we were doing, us being inspired by the music he was creating, that turned that place around. It was watering our real roots again.

The characters that you were responsible for as an animator at Disney are so varied in style and design. You never just did one specific type of character. How would you decide who you wanted to do?

I’m usually drawn to something that’s got this weight to it. Weight of spirit, weight of energy, physical weight. There’s a sculptor in me that finds it really fascinating when you look at a Rodin sculpture and you see a tenderness in the eye of someone he is sculpting. It doesn’t have to be a villain, though at the beginning I thought that that’s what I needed — a villain to really communicate that kind of powerful energy, force. But then I heard Jodi Benson sing “Part of Your World” [for Little Mermaid]. I was supposed to do Ursula because I was doing the bigger characters. But I heard and saw in her interpretation of that song, “Part of Your World,” a greater power — this power of believing that the impossible is possible. I just thought, Oh, whoa. That is the brightest light. I got to animate that. And that’s pretty much what’s been driving me since.

You have animated some of the most iconic characters in movie history: Ariel, the Beast, Aladdin … Is there one that jumps out as one you wish had been better appreciated?

Yeah, yeah, definitely. Silver in Treasure Planet. I mean, that guy was so true to my growing up as a teenager. I knew somebody — my coach in football, this guy, Micky Ryan — who had the same speech that Silver gave to Jim Hawkins: “Someday I’m going to see the light shining on him and off you.” I lived that. I put my heart and soul into creating that guy. And also just the connection of CG and hand-drawn blended into one character; I just felt like this is defining everything of who I am as an animator — the heart, the passion, the humor, the weight. Everything about him. And then to see it sacrificed in a political battle that went on between Michael and Roy at that time, where [the film] was written off as a loss after, I think, almost two weeks. No one went to see it. I have to say, it’s one of the most beautifully animated films. There was this authenticity to Silver that I thought was really remarkable. I loved animating with John Ripa on the same animation desk at the same time, doing tag-team animation of Silver and Jim Hawkins. I’d never done anything like that. It was so real and spontaneous. It was like improv, what we were doing on that film.