Black is in now,” the photographer Beuford Smith tells me, referring to the current vogue among white-led cultural institutions and capitalist pursuits for tapping into the wellspring of our Black matter and belatedly recognizing and compensating Black artists for their labor. Smith is president emeritus of the Kamoinge Workshop, a fine-arts collective of Black photographers that formed in New York in 1963 and is the subject of a group retrospective, “Working Together,” which opens later this month at the Whitney Museum after originating at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. Much of it is not familiar even to students of photography; all of it should be. The show reminds us that Black has always been in: in style, in love, in profundity, in mourning, in school, in danger, in the streets, in black and white, in color. These artists have spent a lifetime “taking the mundane and bringing the beauty out,” as Miya Fennar says of her late father, Al Fennar, whose work is among that of the 14 photographers presented in the show.

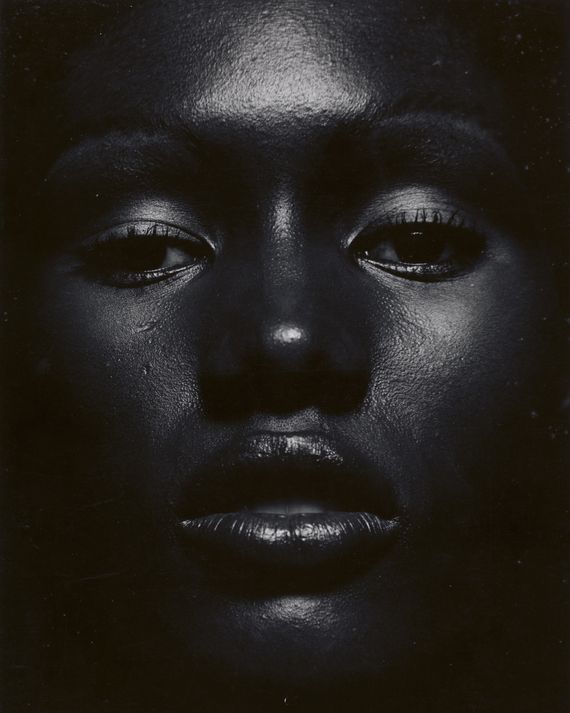

The Kamoinge Workshop members sought to distinguish themselves from commercial photographers at a time when photography was just gaining some traction in its argument to be accepted as fine art. But their audience was not some (white) critical Establishment so much as one another — the toughest, though most loving, critics around, crucial to their artistic growth — as well as all Black people, who were their subjects, seen just being, which is to say, fighting for relevance in every corner of life in the U.S. and everywhere Black people were oppressed. There was enough of the white gaze around taking photos of Black bodies (however sometimes well intentioned). Moreover, Black people were not only the focus of the workshop’s camera lens but also the recipients of its teachings: Kamoinge’s legacy is founded on the mentorship of youth who were exposed to life outside their block; if art was on the path they wanted to take, the group built the path and set them on it. In some ways, it was like a school: They saw films, had assignments.

Roy DeCarava, Louis Draper (whose work, posthumously acquired by the VMFA, was the seed for the Kamoinge Workshop show), and other founding members were there to guide and inspire the next generation. DeCarava, already a prominent photographer by the 1960s and the winner of a Guggenheim fellowship in 1952 (the first Black photographer to receive one), was the president of the Kamoinge Workshop for its first two years. He knew the worth of his people and was willing to divest from any Establishment — he was one of 15 artists to pull out of the 1971 show “Contemporary Black Artists in America” at the Whitney Museum and protested Life magazine for its lack of Black photographers — that did not take seriously the “penetrating insight and understanding” of his peer artists. DeCarava was the glue that kept the family together. He recruited photographers, led critique sessions, lectured on everything from tonality to the arbitrary relationship between color and emotion, lent equipment, and helped lay the artistic and philosophical foundations of Kamoinge.

“None of us got anywhere without help,” says co–founding member Jimmie Mannas. “It started with our own families growing up. They supported us. It was the same in Kamoinge. Roy DeCarava was our teacher. His wife fed us … Sometimes she was a harsher critic than Roy was!”

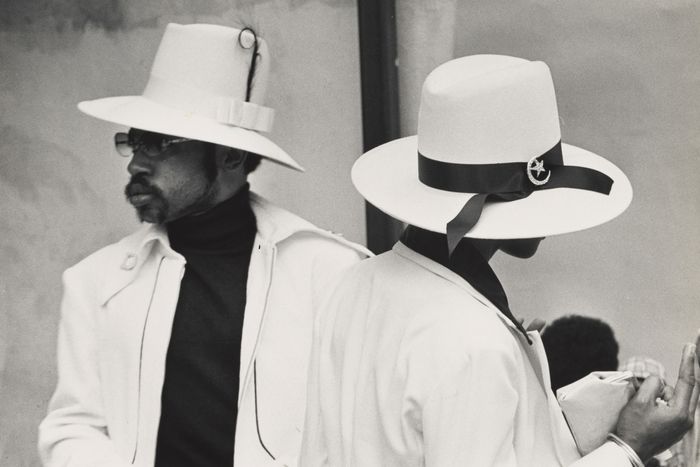

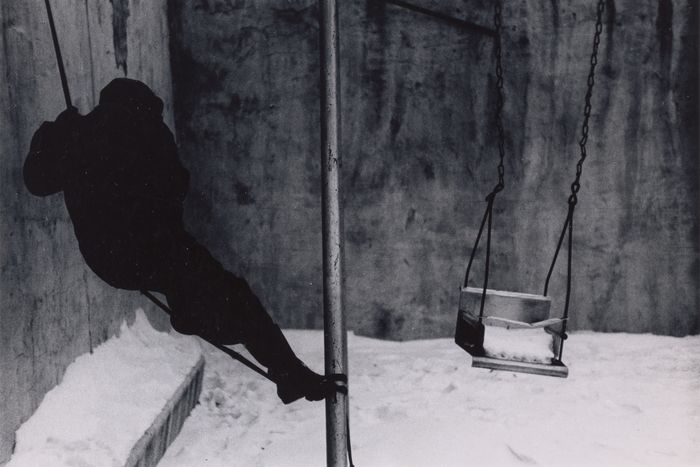

The Kamoinge Workshop was rooted in New York City: Harlem, Clinton Hill, Greenwich Village, the Lower East Side, Bedford-Stuyvesant. The subjects and formats of the show range from a portrait of Grace Jones, who sat for Anthony Barboza, to street photographs shot from the hip — like Footsteps, in which Adger Cowans captures a solitary pedestrian leaving a trail in the snow — to people in their Sunday best in front of Baptist churches and Black families in all manner of celebration.

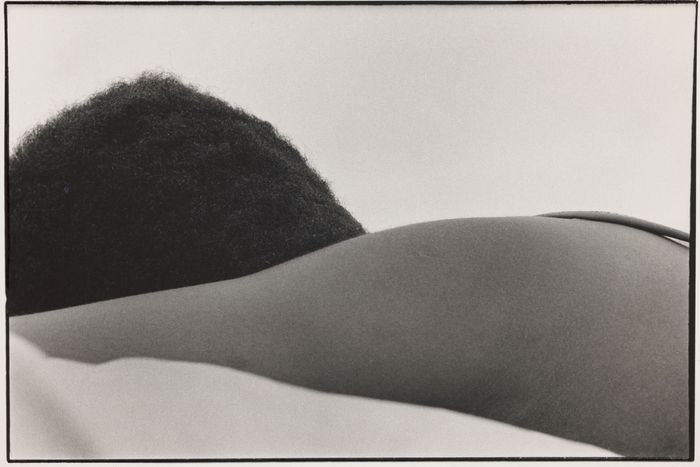

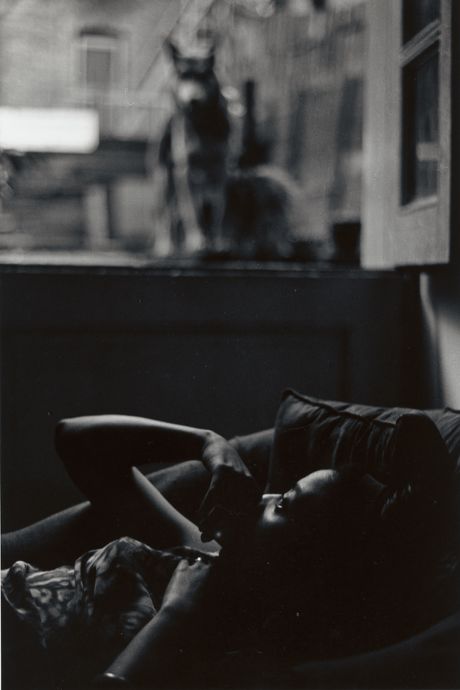

In Shawn Walker’s Family on Easter, Harlem, NY, everyone is wearing all white. Baked into each photograph are the uncounted moments of waiting for the right time to capture the subjects’ spirit, the hours spent developing film with meticulous attention to contrast and other elements in the darkroom, the artists’ active manipulation of light, the control and contemplation of the shutter. Kamoinge may mean, in the language of the Kikuyu people of Kenya, “coming together” or “working together” for a common cause and common purpose — in this case, pushing positive, dignified representations of Black people into the consciousness of consumers of both false media and exclusive pieces of art — but every artist in the workshop had a unique fingerprint. Kamoinge is a family, but its members are not the same and shouldn’t be confused as such. Group members sought self-actualization in the world as well as within the context of the group.

Cowans studied photography in the Midwest and was tapped as a founding director of Kamoinge around the time he was working for Gordon Parks (not a member). Cowans found himself in the middle of a lot of Black folks who loved photography but who didn’t have the technical background he did. Then he was teaching Kamoinge members how to use a light meter and when to use different cameras for different visions. He introduced other members to the wide-angle lens. Kamoinge provided these photographers with a rigorous education, and praise was hard earned. They spent a lot of time ripping one another apart before having wine and paella or chili. Daniel Dawson recalls a session during which a photographer was told to “take that shit out of here until you know how to print.”

Ming Smith, who cites Kamoinge as the catalyst for her explosive journey into photography as an art form, has an Aperture monograph coming out on November 10, for which she thanks her ancestors for their blessings as she births this project; Mannas’s work is in the process of being acquired by the Library of Congress, and he’s working on multiple projects; Walker’s archive was acquired by the Library of Congress earlier this year; Barboza is hoping to self-publish a collection of photographs (which in the current moment have individual price tags of tens of thousands of dollars); Herb Robinson is focused on historical memory, making sure that the names and work of those Kamoinge artists who have passed — Ray Francis, Herman Howard, and Fennar — are not forgotten by actively tracking down and cataloguing their archives; Beuford Smith, fervent street photographer, is gradually making his way back out to snap photos in Harlem, his artistic and geographical home; Walker envisions an exhibition of the “village” of his 117th Street block in Harlem that raised him; Herb Randall doesn’t have anything new in mind, per se — he just wants to wrap his hands around his camera, go out into the world, and prime his mind for what his eyes may see and what his heart wants to say next.

The value of the Kamoinge collective’s work exists in its painstaking composition, heart, and razor-sharp technique. It would be unjust, and frankly a shame, to pigeonhole and tokenize these artists. As Dawson tells me, “We were never starving to be white; we were valid as ourselves.”

“Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop” opens at the Whitney Museum on November 21.

*This article appears in the November 9, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!