Netflix is a service built around the idea of giving consumers the ability to watch what they want, whenever they want. There are no time slots or channels or program schedules in its version of television — just endless rows of content ready to be streamed at the click of a button. That’s how things have worked since the days of Lilyhammer and House of Cards (okay, actually even before then), and there is no reason to believe the company has any interest in changing that fundamental way it distributes programming.

But that doesn’t mean the streamer might not be open to at least flirting with some other models.

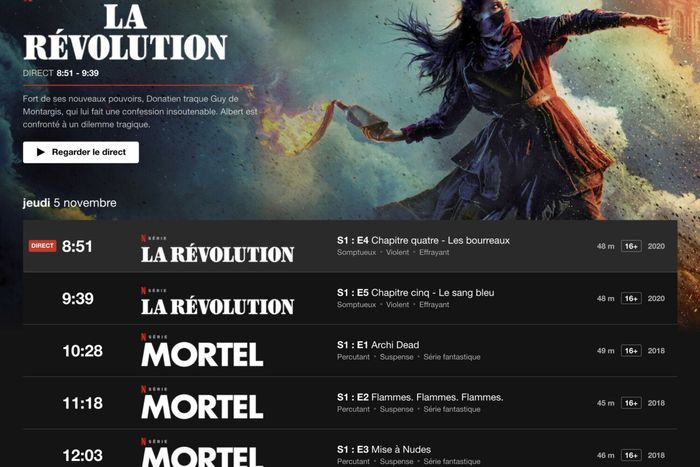

Last week, Netflix France announced it had begun testing a new feature that basically lets subscribers watch a version of the service that looks and feels like a traditional linear TV channel. It’s called “Direct,” and the company describes it as “a web-based experience that’s the same for everyone who watches it: a real-time service that gives our members in France some of the best French and European content” from the Netflix program library. Per Frandroid, the current incarnation of Direct presents users with a 24-hour grid so they can see what’s coming up next on the virtual channel, with programming refreshed every few days based, at least in part, on what’s popular among all Netflix France subscribers. Right now, Direct is only available to a small percentage of French Netflix subscribers, but the company says it will roll out nationwide on December 5. “We’re always looking at new features to help our members discover great shows and films more easily,” a Netflix spokesperson told me via email. “We experiment with these types of tests in different countries — making them more broadly available if people find them useful.”

Netflix’s post announcing Direct said it had chosen France for the test because “watching traditional TV remains hugely popular with people who just want a ‘lean back’ experience where they don’t have to choose shows.” So-called “lean-back” viewing is not a phenomenon limited to France, however. In the United States, for instance, TV consumption via linear channels still far outpaces tune-in via connected devices, at least among viewers over 35. So while Netflix may be testing Direct out first in France, don’t be shocked if the company ends up expanding the function to other territories, including the States, if data supports such a rollout. It is not uncommon for Netflix to test new features for six months to a year or more before making a call on wider distribution. Back in fall 2019, for example, a small number of users suddenly got the ability to adjust playback speed on mobile devices; it wasn’t until this summer that the streamer made it available to anyone using an Android phone or tablet.

At first glance, it might seem odd that Netflix would turn back time by launching a linear feed of its programming: Why bring back a viewing experience that dates back to the 1950s when your whole brand is built around reinventing television? But the decision to launch Direct actually makes sense when you think about one of Netflix’s most important missions right now, which is figuring out how to help members discover and sample its bountiful offerings. While the company is far from done signing up new subscribers, in more mature markets such as the U.S., where the company already reaches well over half the population, it is probably more important to find ways to retain existing customers. You do that either by coming up with more must-stream programming — or by innovating new ways to get audiences invested in shows and movies they don’t even know exist.

That’s where Direct could be useful. Netflix is well aware of the fact that many of us often spend five or ten minutes — sometimes more! — scrolling through its content rows looking for something worth watching. Sometimes, users simply give up and exit the app altogether. It’s no big deal if that happens every so often, but folks who are continually frustrated by the sense that there’s nothing worth watching on Netflix may be more inclined to cancel their subscriptions. It is thus very much in Netflix’s best interest to get you to watch something each and every time you start poking around its vast content universe. And over the last year or so, we have seen the company step up its efforts to do just that. Those top-ten lists of movies and TV shows that started popping up on your Netflix homepage earlier this year, for instance, weren’t about the company trying to be more transparent about who’s watching what on the service. Nope, they’re designed to encourage members to check out content others are already watching. And while it’s still in testing mode, since late 2019, some Netflix users have had a “shuffle play” functionality in their apps that, when selected, instantly begins playing an episode of a show or a movie. Once again, the point is to #StopTheScroll and get viewers streaming something.

Netflix’s Direct is arguably much more radical than the two aforementioned ideas, or at least more divorced from the company’s previous, almost dogmatic insistence that consumers should have complete control of their viewing experiences. As far as I know, this is the first time Netflix has offered any sort of programming feed curated (at least partially) by humans and not personalized for individual users. The shuffle button, for example, relies on the company’s algorithm to find content subcribers might want to sample: What you’ve already watched on the platform helps determine what “random” show you see when you press the button. The top-ten lists are also the product of what the data tells Netflix audiences are watching, or so the company claims. (The sheer randomness of some the movies and shows which end up on the lists suggests the titles aren’t exclusively the product of Netflix’s programming team deciding which big bets need to end up in the top ten — though I’m still skeptical the streamer doesn’t take steps to make sure certain showrunners don’t call up Ted Sarandos screaming about their latest release not making the cut.)

But while the content of Direct is apparently influenced by what’s currently popular on Netflix France, it is still a linear (if virtual) channel where shows end up in time slots and only “air” on certain days. And this opens up all sorts of new possibilities for the streamer. There is no reason Netflix couldn’t easily slot in a marathon of five episodes of The Crown season three on Direct to drum up interest in the new season dropping this week. It could “program” kids’ shows to stream in the morning and more adult dramas or stand-up specials to show up late at night. In other words, Netflix — if it wants — now has the ability to use Direct as a promotional vehicle to get audiences interested in shows which maybe aren’t getting noticed as much as its development teams had hoped when they were green-lit. Netflix already does this by making sure content gets prominent placement on user homepages, but Direct takes things a step further by making it so users don’t even have to press play to begin watching an episode.

So what led to this? I have no idea what sort of internal debate there has been at Netflix over the wisdom of trying something like Direct. It could well be that the notion of a linear feed is simply too old-school for the Netflix audience, particularly those under 30 who came of age in an on-demand era (remember, before Netflix, there were DVRs). Direct may never get beyond the testing phase; it could also just end up being something the company offers in a few countries. And while the fact that Netflix will make Direct available to everyone in France next month, and not just a small subsection of subscribers, suggests the company is serious about the idea, it is equally notable that (for now) the product is only available via website and not part of the actual Netflix mobile or TV apps. I assume that will change at some point, but if not, then I think we can conclude Netflix isn’t all that serious about the idea just yet.

I am actually hoping Netflix leans into Direct, and not just because I am a dinosaur who still believes there’s a place in the world for linear TV of some sort. TV in which audiences control when and how they watch is obviously better than the bad old pre-DVR days of network schedulers pitting your favorite shows against each other. It’s certainly better than the current network landscape, where episodes of shows roll out seemingly at random over the course of nine months. (Does anyone at ABC — other than folks in the ad sales department — really think it makes sense to bring back Grey’s Anatomy this week, air it for a few weeks, and then put it back on the shelf until February or March?)

But I think Netflix would do well to continue to play around with programming models and not stubbornly insist the only way to release shows is to drop full seasons all at once in the middle of the night. Its unscripted division built interest in The Circle and Love is Blind by spreading out the release of new episodes over three weeks. Why not use something like Direct to premiere the first episode of new shows a few hours (or days) before full seasons are released? Or maybe a full season of a returning comedy series such as Big Mouth debuts via a five-hour marathon on the Direct feed just before all episodes become available on-demand. Netflix wouldn’t really be going against its pro-consumer ethos here, and the promotional benefits could be enormous. I think Netflix’s films could benefit even more from getting a primetime premiere on a linear channel before being dropped into the streamer’s giant content library.

The danger, of course, is that such techniques could overcomplicate things for subscribers. Netflix has thrived in part because of how simple and consistent it has been in releasing 99 percent of its programming. You don’t want to create an environment where audiences start worrying about time slots or whether a show is on Direct or “regular” Netflix. Hulu and Amazon have probably hurt themselves a bit by having some shows release episodes weekly while others drop all eps at once. But as long as Netflix doesn’t overdo things, I think having a linear feed (or even a couple of feeds devoted to different genres, such as movies or reality shows) only adds to the user experience. Netflix’s blog post for Direct admits audiences don’t always want the pressure associated with choosing what to watch. “Maybe you’re not in the mood to decide, or you’re new [to Netflix] and finding your way around, or you just want to be surprised by something new and different,” the company notes. Direct seems like a great way to serve those viewers.

Disney+ Numbers; Streaming Service Shuffles

• Disney just reported its third quarter earnings, and there’s nothing Goofy about how well Disney+ is doing: The streaming service added 16.2 million customers last quarter. You could tell the company was already feeling good thanks to an earlier announcement it made on Thursday: WandaVision, the first big Marvel Studios show for Disney+, has pushed back its expected December debut until January 15. While no actual premiere date was ever announced, until recently, the streamer had been including the show in promos touting its 2020 releases. A December premiere made sense since that’s when season two of The Mandalorian is expected to wrap, and a big tentpole such as WandaVision is a great way to make sure fourth quarter subscriber numbers stay strong. But the streamer will already have the finale of Mandalorian plus the straight-to-streaming premiere of Pixar’s Soul on Christmas Day. And who knows, maybe another feature film is about to be added to the Disney+ calendar? In any case, if Disney is feeling really good about where things stand at Disney+, WandaVision will probably be more useful helping goose the streamer’s first quarter 2021 numbers.

• ViacomCBS is shutting down some of its smaller streamers. This isn’t a complete surprise, but during an earnings call last week, the company confirmed that niche platforms such as MTV Hits and Comedy Central Now will be going away over the next few months. The reason: Much of the content from these microservices has moved over to CBS All Access ahead of the latter’s transformation into Paramount+ next year, and there simply aren’t enough subscribers to justify keeping them around. In 2018, WarnerMedia did something similar ahead of the launch of HBO Max, pulling the plug on services such as FilmStruck, Drama Fever, and Super Deluxe. But despite some media reports to the contrary, Buffering has confirmed there are no plans to shut down the ViacomCBS-owned BET+ or Noggin, both of which have bigger subscriber bases (and, in the case of BET+, a lucrative partnership with Tyler Perry).

• While ViacomCBS is consolidating its streaming empire a bit, AMC Networks this week talked up the value of a more targeted approach. The independent company told investors its portfolio of specialized streamers (Acorn, Shudder, Sundance Now, and UMC) is on track to end the year with more than 4 million combined subscribers, beating its forecast of 3.5 million to 4 million subscribers by the end of 2022. “We are fully two years ahead of plan and are far exceeding our earlier expectations,” AMC Networks president and CEO Josh Sapan said. What’s more, Sapan said when the recently expanded AMC+ service (which now has content from a broad array of AMC-owned platforms) is included, the company expects to have between 5 and 5.5 million SVOD customers before the year is out. “In just 12 months, we’ve also doubled the amount of revenue for our company coming from the streaming business,” Sapan noted. While AMC Networks seems to be having success operating several smaller streamers, I do think eventually it will make sense for the company to expand AMC+ even more, folding in more content from Acorn (which has a wealth of compelling programming from the U.K and Europe). And long term, the big question for 2021 is whether AMC Networks survives as a stand-alone company or gets snapped up by a bigger fish.

The Time Capsule: Come Aboard The Love Boat

Love: Exciting and new … and now on CBS All Access. I am not lying when I tell you that for several years now, I’ve been quietly lobbying execs at ViacomCBS (and previously CBS) to add reruns of Aaron Spelling’s classic comedy-drama The Love Boat to their signature streamer. The company owns the rights to the show and has aired reruns on its cable network Pop TV for years. But for some reason, the series had been unavailable to stream anywhere in the U.S. — until a few days ago. Earlier this month, and without any fanfare, CBS All Access (soon to be Paramount+) added nine of the show’s ten seasons to its lineup. (Season ten isn’t yet on the service, but hopefully will be added soon.)

Look, I’m not going to pretend The Love Boat is great TV: It’s corny, the acting is over the top, and storylines are often ridiculous. But it’s an amazing time capsule of 20th-century pop culture, since so many actors who were stars in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s ended up doing a guest turn (or five) on the show. Some were celebs well past their peak pop culture relevancy who were just looking for a paycheck and a good time (an Ethel Merman or Raymond Burr); others stopped by on their way to future stardom (like Tom Hanks.) But almost every episode features at least one recognizable name hamming it up in the best way possible. And the best ones feature an appearance from the ever-talented Charo (whose Twitter feed is a constant source of joy.) For this week’s time capsule, check out her performance of the show’s theme song.

Parting Shot

“Quibi took everything that is Hollywood and nothing of what was truly a startup, with its top-down model, OG deals, dick swinging, and star-fucking. Take the worst parts of Hollywood, bake it into a phone, and that’s what you got.”

— Producer and former network exec Evan Shapiro talking to Bloomberg Businessweek about the failure of Quibi.