John le Carré died on December 12, 2020. We are republishing this piece from September 2017 in commemoration of his work.

Nearly three decades ago, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the U.S.S.R., John le Carré retired his greatest character, the potbellied English intelligence agent George Smiley, and turned away from Cold War, great-game spy novels toward one-off thrillers about gangsters, terrorists, and arms dealers. But with Western Europe tilting toward populist turmoil and grappling with new consequences of the communism’s fall, le Carré couldn’t stay away. In his new book, A Legacy of Spies, Smiley — beta spymaster bureaucrat, cuckold savior of liberal Europe — finally returns. It’s the best news in international relations all year.

If you’ve never read le Carré’s Smiley series before, A Legacy of Spies is an excellent excuse to start. (You could read A Legacy of Spies without reading its predecessors, but you’d miss out on some key details and characters.) The basic pitch is this: George Smiley is the anti–James Bond. Unlike Bond, he is fat and poorly dressed; unlike Bond, he toils away at a drab intelligence agency, abstrusely referred to as the Circus, permanently plagued by bureaucratic infighting and petty office politics. Unlike Bond, Smiley is married, and his wife dislikes him and cheats on him. Unlike Bond, Smiley regards the necessary violence and mendacity of espionage as a real moral problem, rather than a fun adolescent fantasy.

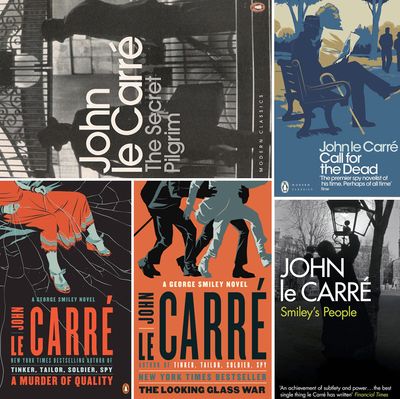

Also unlike Bond, Smiley is the star of several smart, well-written novels. Rare among thrillers, the Smiley books — there are nine of them, including A Legacy of Spies — score highly in both the qualities that people pretend to like in books (formal style, psychological portraiture, political intelligence, moral sensibility) and the qualities that people actually like in books (sex, violence, plot twists, convincing and frequently deployed spy jargon). Collectively, they form the best espionage series ever written.

The only question is where to start. The Smiley books don’t need to be read in chronological order, and, frankly, probably shouldn’t; it’s much more rewarding to jump around, skipping the experiments (the second Smiley book is a murder mystery, not a spy book) and lackluster sequels until you’re really hooked. The truth is that God intends us to read thriller series in odd and disjointed orders as we find individual episodes dog-eared in used-book stores and beach-house rentals, but if I wanted to undertake the worthwhile project of reading through le Carré’s Smiley novels for the first time, this is the order that I’d recommend.

The Stone Classics

1. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963)

Smiley is only a side character in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, the story of an embittered double agent sent to infiltrate East German intelligence, but you should start here anyway, because this book is so freaking good and also because it’s the clearest and most direct articulation of the questions that animate le Carré’s work — stuff like What if Western democracy is a self-deceivingly immoral enterprise, devoid of values and rotting from the inside? What if communism … isn’t? What if spying is, instead of sexy and fun and heroic, awful and degrading and really bad for your liver? That a book that can engagingly ask those kinds of bad-dinner-party questions and be as gripping and unforgettable as The Spy Who is a testament to le Carré’s mastery of plot and pacing.

2. Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974)

Once you’re onboard the Smiley train, the next stop comes a decade later at the other le Carré touchstone, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, a heavily fictionalized account of the hunt for the real-life British intelligence mole Kim Philby. Here, Smiley’s actually the protagonist, brought back from retirement to sniff out the mole among the preening idiots and ambitious frauds who were formerly his rivals. Tinker Tailor is a masterfully plotted work of overlapping timelines, and contains some of le Carré’s most brilliantly rendered character portraits, but if I’m being honest, the real reason I love it is that I’m a sucker for confidently and convincingly deployed spy jargon and narratives that teeter on the edge of incomprehensibility as they hurtle toward their conclusions.

Early Smiley

3. Call for the Dead (1961)

Now that you’re familiar with Smiley and his universe, it’s interesting to turn back to his origin, in le Carré’s first book, Call for the Dead. That Call for the Dead is, essentially, a mystery novel — Smiley investigates the mysterious suicide of a British civil servant — suggests that le Carré was maybe planning a career as a more conventional crime writer, but he seems unable to avoid writing a le Carré book, down to the final confrontation between a deeply conflicted Smiley and a wartime friend turned Cold War foe. Note that if you’re really desperate to read A Legacy of Spies, after Call for the Dead is a good moment in your read-through to do so — most of what’s referenced in it comes from The Spy Who, Tinker Tailor, and this book. (Ignore for everyone’s sake that Smiley gets a new birth date sometime between this book and Tinker Tailor.)

4. The Looking Glass War (1965)

For now, you can skip A Murder of Quality, the second Smiley novel, and move directly to The Looking Glass War, the follow-up to The Spy Who and the Smiley novel with the least Smiley in it. Looking Glass War tells the story of a decaying agency known as the Department, a rival to the Circus, mounting a dangerous operation in East Germany as a final grasp at relevance. If in other books le Carré hints that intelligence-gathering is a useless activity — irrelevant to national or international security, and ultimately performed in service of the petty organizational politics of careerist bureaucrats — in Looking Glass War he comes out and says it. It’s his bleakest work, but its portrayal of the way otherwise-laughable windbags and forgotten true believers can stumble their way into causing monumental harm is, uh, still relevant.

Karla Trilogy

5. The Honourable Schoolboy (1977)

Now that you’ve caught up on the bulk of Smiley’s history, it’s time to finish the Karla trilogy, the three-book cycle, begun in Tinker Tailor, that traces Smiley’s pursuit of his opposite number in Russian foreign intelligence — a forbidding and remote figure called Karla. The Honourable Schoolboy is not going to be anyone’s choice for favorite Smiley novel; it’s more confusing than Tinker Tailor for a much less satisfying conclusion. But it gets the Circus characters out of Europe, on a chase after a money-laundering network in Southeast Asia, and portrays for the first time the fraught relationship between a humiliated British intelligence service and its ruthless and imperious American allies in the CIA.

6. Smiley’s People (1980)

Even more importantly, maybe, The Honourable Schoolboy sets up Smiley’s People, the grand conclusion not just to the Karla trilogy but to the entire Smiley series (more or less — see below). Smiley’s People is about Smiley — out of retirement for the 6,000th time — investigating a mysterious death — for the 6,000th time — that might lead him, finally, to Karla. But its focus is less the investigation itself than the consequences of a lifetime of work as a spy: the agents and assets cast off or left behind, the relationships ruined or buried, the violence and death left in the wake of maneuvering for scraps of likely useless intelligence. And if that doesn’t convince you, well, Smiley’s People features an extremely awful and hugely entertaining portrayal of German hippies. It’s a nice way to say good-bye to literature’s least libertine spy.

Ephemera

7. The Secret Pilgrim (1990)

Of course, Smiley doesn’t disappear entirely after Smiley’s People — he returns, sort of, in The Secret Pilgrim. Smiley’s role is officially as a lecturer to a class of new recruits, but he exists in the book mostly to spur the main character, Ned, a former spy, into recounting stories from the glory days of the Circus. The Secret Pilgrim, le Carré’s first book to be published after the revolutions of 1989, isn’t essential Smiley, especially since he appears in it only intermittently, but it’s a comparatively light read, and a funny time capsule from a moment when every spy writer alive must have been wondering what their next novel would be about.

8. A Murder of Quality (1962)

There’s nothing bad about A Murder of Quality, the second Smiley book; it’s just that it’s not really a spy book. During one of Smiley’s many periods of retirement from the Circus, he’s asked by a friend to look into (you guessed it) a mysterious murder in a conflict-riven university town. If you like Smiley, and le Carré, and Very English murder mysteries, you’ll like A Murder of Quality. Just don’t expect any spy jargon.