WNBA player Elizabeth Williams of the Atlanta Dream remembers watching the documentary With Drawn Arms in early September in “the bubble.” That is, sequestered within the elite Florida sports academy where the women’s basketball league quarantined from the novel coronavirus for the duration of 2020’s weird, isolated, 22-game season.

In the aftermath of outrage caused by the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, the WNBA took arguably the most strident and sustained political action of any professional athletic organization in history. Players kneeled during the national anthem; they wore warm-ups emblazoned with Black Lives Matter affirmations, organized media blackouts, and most pointedly, refused to play on back-to-back days in August in response to the police shooting of unarmed 29-year-old Black man Jacob Blake. “The games resume tonight,” the WNBA said in a statement at that time. “The fight for justice and equality never stops.”

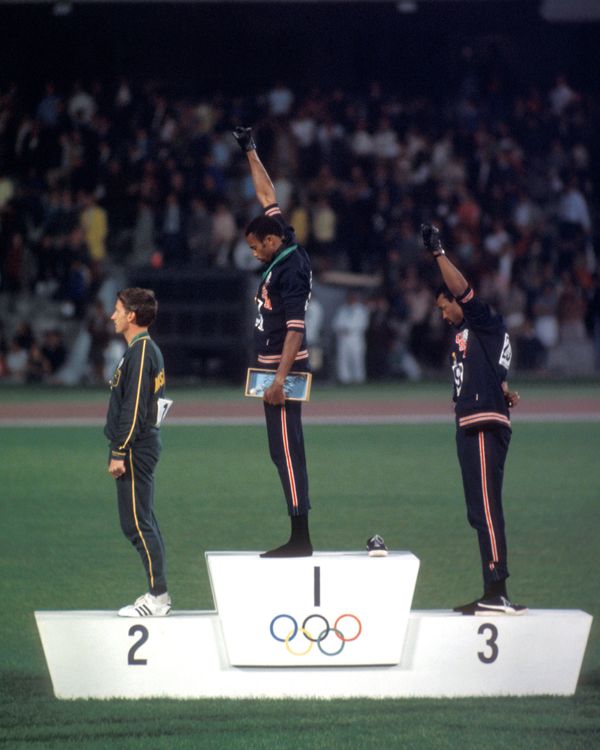

To hear it from Williams, With Drawn Arms arrived as something close to the perfect film for that post-Kaepernick cultural moment. Informally screened for players in both the NBA and the WNBA ahead of the documentary’s October premiere at the Hamptons International Film Festival, it chronicles Tommie Smith’s singular path from athleticism to activism — Smith, of course, being the gold medal-winning American sprinter who raised a black-gloved fist atop the victory platform at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. But it wasn’t until Williams’ second time watching the movie — which began streaming on Starz last month and premiered on the multi-platform entertainment network Bounce on December 13 — that the 6-foot-3 center/forward made the connection between the Olympian’s defiant gesture beneath the world’s media spotlight and the broader culture of protest it ultimately spawned.

“It was a reminder about why all this started — how symbolic it was,” says Williams. “There were teams in the bubble that took a knee and raised their fists. That was Tommie Smith’s form of protest. And it’s been consistently seen in protests now for a lot of Black people. I think for a lot of us, hopefully we can take something from that and inspire people to make changes in their own way too.”

Just months onward from the Milwaukee Bucks refusing to take the court for an NBA playoff game, the postponement of three Major League Baseball games, and shelving of five Major League Soccer matches all in support of the Black Lives Matter movement — all in explicit protest of continued police shootings of unarmed Black people across the country — the intersection of sports and popular political dissent has become entrenched as one of 2020’s defining flashpoints. Understood within that context, Smith (along with bronze medalist John Carlos, who joined him in raising a gloved fist in 1968) has never seemed more influential: the first sportsman to leverage the attention drawn by his athletic excellence to amplify broader social justice ideals.

To be sure, previous documentaries have trafficked in Smith and Carlos’ now-familiar story. The Stand: How One Gesture Shook the World (which also came out this year), HBO’s Fists of Freedom: The Story of the ‘68 Summer Games and the Australian-produced Salute (2008) all assiduously recount the Age of Aquarius political tumult, the Black Power and Olympic Project for Human Rights movements that backdropped the games that year, and the chain of personal events that compelled both men to shock the world in their moment of glory.

With Drawn Arms, however, closes the loop on Smith’s hero’s journey. In addition to framing the public vilification and immense personal cost involved with his making what was widely but incorrectly perceived at the time as a separatist salute — including being banished from competitive sprinting, death threats, homelessness and addiction — the film showcases a reconciliation of the athlete’s place in the national conversation around race that took place only fairly recently.

Thanks to an introduction made through With Drawn Arms co-director Glenn Kaino, the former medalist is shown being enthusiastically greeted by President Barack Obama at the White House. The filmmaker also helps arrange for Smith to receive the ultimate sports benediction: his photo on a box of Wheaties. And further, the polymathic, ludicrously well-connected filmmaker helped arrange for Smith’s personal effects from the Mexico City 1968 games, such as an Olympic tracksuit, Olympic Project for Human Rights pin and the Puma cleats he wore during his world record-setting victory, to be donated to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture. (Last year Smith was inducted by the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee into its Hall of Fame not just as an athlete but under the rubric “legend: track and field.”)

Given With Drawn Arms’ partisan quality — insofar as the documentary actively rehabilitated Smith’s historical legacy — it is perhaps fitting that the film didn’t even begin as a work of nonfiction reportage. Kaino, 48, had never directed a feature or a documentary before taking on Smith’s story and the whole thing came about through his day job as a pioneering conceptual artist. Kaino’s large-scale installations and multimedia sculptures have been shown at such prestigious events as the Whitney Biennial, Desert X, the Biennale de Lyon and the Frieze Art Fair; many of the pieces exploring “otherness” through jarring collisions of cultural flotsam.

Initially intending to “re-dimensionalize” Smith through art, Kaino connected with the athlete via a mutual friend. Then he and Smith worked together to create the 2013 art installation Bridge: a 100-foot-long suspension construction made of dozens of gold-painted fiberglass resin casts of Smith’s outstretched fist and arm (first shown at the Chicago Art Fair). About a year into their collaboration, which extended to a number of other artworks that have been shown at major exhibitions throughout the country, Kaino brought in his eventual co-director Afshin Shahidi (an Iranian-American photographer turned cinematographer-documentarian who got his start working for Prince) to film the conversations at Smith’s home in Georgia without any explicit plan to make a movie.

“When I first met Tommie, I saw the tension between his personal stakes in that image of this very defiant gesture and the way the world was trading in that image,” Kaino says. “I would see him slip into a ‘talk track’ that he was conditioned to tell about the story. I felt, ‘I’m hearing the same story that 50 other journalists over the past 35 years have heard.’ I really tried to get us into a generative space where we were going to do something new together.”

As filming commenced in 2014, a certain confusion surrounding the social phenomenon of the “Angry Black Athlete” remained unresolved within the public psyche and Black Lives Matter was just beginning its rise to prominence as a political movement. When San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick drew blistering opprobrium from the NFL and conservative leaders in 2016 for sitting then later kneeling during the national anthem (to highlight how America “oppresses Black people and people of color”), however, the filmmakers realized their subject had gained a new cultural traction. “We didn’t set out necessarily to make a film about what was happening politically,” Shahidi says. “But Kaepernick taking a knee, Donald Trump being elected and then this reaction to Black men being murdered by police — there were all these things that pointed to the urgency of this story. It told us that this was an important story to get back to.”

Originally intended to premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival (before the pandemic struck), the film was executive produced by a coterie of influential African-American cultural figures including John Legend, activist-former Grey’s Anatomy co-star Jesse Williams and music/cultural critic-turned filmmaker Nelson George. It also features an interview with the late civil rights hero John Lewis and the on-camera participation of Colin Kaepernick. But I ask how, as non-Black filmmakers, the co-directors ascertained they had the right sensitivity and perspective to properly frame Smith’s story. “I can answer that question in two different ways,” says Kaino, a fourth generation Japanese-American. “I can tell you my credentials fighting for civil rights ever since I was a young person. Or, I could look at the audience who has come to our creative content and say, ‘This is the America we believe in and who we want to talk to.’ We’re really trying to tell an intersectional story with an intersectional team.”

Adds Shahidi: “We’re telling the story alongside the man rather than using archival material. I think Tommie chose us more than we chose Tommie.”