A week before Christmas, the New York Times announced the findings of its internal review into Caliphate, its acclaimed 2018 audio documentary series that was thrown into question earlier in the Fall. In short, the paper had found considerable fault with the reporting in the series, and as a result, it would be walking back substantial portions of the story that was laid out for listeners.

Quick recap on how we got here. In late September, Canadian authorities arrested a man on the charge of falsely portraying himself as a former member of the Islamic State. That man, Shehroze Chaudhry, was identified as the individual who went by “Abu Huzayfah,” the primary subject of Caliphate whose supposed accounts of life in the extremist group provided a narrative backbone for the series, particularly in its opening episodes. Chaudry’s arrest, and the debunking of his legitimacy as a source, drew considerable scrutiny back to Caliphate, which won multiple awards, including a Peabody and a Pulitzer honor, for its work. The Times initially stood by the podcast’s reporting in the wake of Chaudry’s arrest, but not long after, the paper announced that it was opening a “fresh examination” into the project.

The Times has now declared Caliphate to be faulty in its journalism, noting that red flags about “Huzayfah”/Chaudry’s trustworthiness should have been heeded during the original reporting process. “We fell in love with the fact that we had gotten a member of ISIS who would describe his life in the caliphate and would describe his crimes,” Dean Baquet, the Times’ executive editor, told NPR. “I think we were so in love with it that when we saw evidence that maybe he was a fabulist, when we saw evidence that he was making some of it up, we didn’t listen hard enough.” Shortly after the announcement, the Times agreed to return its Peabody, and a few days later, the Pulitzer Prizes also revoked an honor for Caliphate, at the paper’s request.

There’s been some dispute as to whether the Times’ post-internal review actions with Caliphate amount to a “retraction.” The Washington Post’s Erik Wemple and NPR’s David Folkenflik regarded the move as such, though the Times itself has abstained from using the term. Baquet told the Post that a retraction wasn’t warranted, and a spokesperson told me that while some might technically consider this to be a “retraction,” no content would actually be omitted from the show itself. Instead, all episodes of Caliphate now start with an editor’s note to provide listeners with context around the reporting errors.

I’m reluctant to regard this as hair-splitting, because a formal recognition of whether this actually amounts to a “retraction” is probably meaningful for those within the news business. But from the outside looking in, the damage seems largely the same: the Times has explicitly admitted to severe flaws in one of its widely-consumed news products — featuring a narrative propped up, fundamentally, by the words of a fabulist — which feels distinctly like a consequential concession at a time when the news business as a whole is fraught with struggles over its legitimacy, trustworthiness, and authority among the broader public.

It was a painfully head-turning announcement from the Times, in this context operating as one of the few optimistic stories in the journalism business as well as one of the unambiguously prominent successes in the new audio landscape. But the pain didn’t stop at the acknowledgment of mistakes made during the reporting of Caliphate. The manner of the announcement itself turned out to be messier than the paper had probably intended.

As part of the rollout, Baquet and Mark Mazzetti, an investigative reporter at the Times who participated in the internal review process, sat down for an interview with The Daily’s Michael Barbaro to talk about the mistakes in the production, which was published on the Caliphate feed. There are some who took issue with the very composition of that interview: after all, they say, Barbaro is part of a reporting structure that ultimately leads up to Baquet. I don’t think I agree with this. We’ve seen strong examples of this type of interview in the past, even in the audio business. Consider, for instance, the Michael Oreskes problem at NPR in 2017, and the interview conducted around that time by All Things Considered’s Mary Louise Kelly with then-NPR CEO Jarl Mohn. I get it, though. No matter how effective the interview may be, it’s reasonable to still feel strong suspicion that maybe proper questioning should really be coming from interlocutors who are not financially dependent on the structure being held to account.

If only the messiness stopped there. As NPR’s David Folkenflik pointed out in a (particularly spicy) follow-up report, there were no substantial disclosures about Barbaro’s personal context in relation to Caliphate. Folkenflik cited publicly accessible knowledge that Barbaro’s partner is Lisa Tobin, the executive producer of audio at the Times, who additionally served as the executive producer of Caliphate. And then there were the backchanneling: Folkenflik further reported on instances in which Barbaro had privately reached out to journalists critiquing the Times — Folkenflik, a media reporter, included — and asked them to temper their framing of the story. Whatever the intent may have been, these efforts came off as a campaign to work the refs, an impression that had the additional effect of throwing Barbaro’s interview with Baquet and Mazzetti into further weirdness as it diminishes the presumed journalistic impartiality you’d want from Barbaro in that situation. Indeed, such impartiality was unambiguously present throughout the Kelly-Mohn interview.

So, yeah. There’s a lot going on here. And we haven’t even talked about the even messier matter of Caliphate’s lead personnel yet.

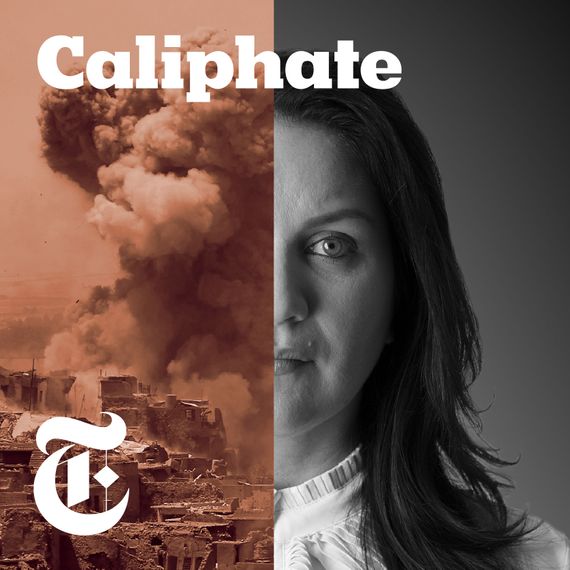

Here we get into exponentially muckier territory. As a result of the Times’ findings, Rukmini Callimachi, the star journalist who led the reporting on Caliphate (and whose face appears on the cover art), was reassigned to a new beat. The move wasn’t framed as a disciplining measure, but rather as a move of practical necessity, reflecting Callimachi’s likely inability to remain on the highly sensitive and difficult terrorism beat, at least for a while, due to the consequences of Caliphate’s reporting lapses.

Callimachi’s reassignment may not be a penalizing measure per se, but it works out to be a penalty in consequence. It should also be noted that controversy around Caliphate can’t be properly divorced from broader controversies around Callimachi herself. Shortly after Chaudry’s arrest in September, The Daily Beast and The Washington Post ran multiple pieces highlighting various threads of criticism levied against Callimachi’s work from within and beyond the Times. A constant theme in these critiques are depictions of Callimachi’s tendency towards sensationalism and privileging narrative over journalism — the very same traits that define the Caliphate controversy. But this dust-up over Callimachi’s history shouldn’t be read as some cut-and-dry matter of good journalist/bad journalist: as I noted in a previous write-up on this story, Margaret Sullivan, a media columnist at the Post who had written about complaints made against Callimachi’s reporting back when Sullivan was still the public editor at the Times, expressed in a Twitter thread published back in the Fall that she felt at least some of the criticism against Callimachi comes “from resentment/jealousy, and that there’s schadenfreude involved here, not without a hint of sexism.”

There’s also the matter of the institution. Back when the post-arrest concerns about Caliphate began to foment, Ben Smith, the Times’ own media columnist, dug into the story himself, ultimately writing a column that painted a picture in which the paper is undergoing a “profound shift… from the stodgy paper of record into a juicy collection of great narratives, on the web and streaming services,” which cultivates an environment in which star reporters like Callimachi, and what her critics would call a tendency of privileging narratives over journalistic tenets, are fundamentally aligned with those institutional market incentives. The Verge’s Ashley Carman echoed this critique in her piece on the Times’ December determination, when she identified this as an expression of the dangers around the modern media intellectual property gold rush, which podcasting as an industry has aggressively internalized as a growth hormone. Put another way: we’re looking at a case study that highlights a risk that’s ever-present for a journalistic institution laboring for power, prominence, and survival in the ruthless contemporary media landscape, where its attempts to expand power also have the capacity to cut into the very fundamentals of modern American journalistic culture.

For its part, the Times had sought to attribute Caliphate’s faults to institutional failure, presumably as a way to head off narratives that may portray Callimachi as being some uniquely bad actor in this situation. If that was the intent, there were issues with the follow-through.

Despite assertions of institutional failure, Callimachi — who, again, adorns Caliphate’s cover art — still overwhelmingly became the face of this scandal. Her journalistic history was picked over by competing publications, absorbed as yet another flashpoint in broad on-going industry-wide debates over the Times and its shortcomings. Some of these critiques have merit (personally, I’m moved by the argument that Caliphate’s possible sensationalism had negative influence on actual policy), but the bigger picture here is that we still have a situation where the individual, not the institution, ultimately bore the bulk of the penalty.

Could the Times have done more to shift that burden between institution and individual? I’m not sure. This may well be the natural consequence of an organizational shift that emphasizes star reporters. In any case, there’s also another issue at play here: what many in the audio community would see as yet another expression of severe gender disparity.

Regardless of what the cover art suggests, Caliphate was a two-lead project. Callimachi may have led the reporting on the podcast, but the show’s spotlight was equally shared by Andy Mills, a (male, white) staffer on the Times audio team who served as the lead producer on the project, who is also credited as a reporter on the story, and who also appears in the show itself alongside Callimachi. Indeed, Mills was the person who gave the speech when accepting the now-returned Peabody.

A few days after the Times announced its findings on Caliphate, Mills guest hosted The Daily, the paper’s flagship podcast. The stark difference in outcomes between Caliphate’s two leads didn’t go unnoticed: one is moved to another beat and becomes subject to intense scrutiny, while the other is almost immediately given the opportunity to guest host one of the most prominent podcasts in America. This split evoked an all-too familiar frustration: who gets to fail, and who gets to fail upward?

To be sure, there are plausible counterarguments. For example, you could theoretically chalk up differences between outcomes for Callimachi and Mills to the nature of their respective roles: working the terrorism beat is an inherently sensitive and volatile position where any mistake can fundamentally compromise the role, while you generally get more latitude to err when it comes to life as a generalized audio producer. In other words, perhaps this is a terrorism beat thing, and not a gender thing. But could it really just be that?

There is also significantly more to the story of Mills. His appearance on The Daily so quickly after the Caliphate admission reignited old frustrations, anger, and concerns among the audio community about Mills’ own history. Some of this has been publicly documented, particularly in reporting by The Cut about the 2017-2018 reckoning at New York Public Radio, which was in part about that institution’s history of cultivating an environment that allowed for sexual harassment, bullying, and discriminatory behavior with little option for recourse. In that piece, several paragraphs were dedicated to allegations of improper behavior made against Mills during his time at NYPR, which included unwanted contact, bullying, and sexist insults targeting women. Most of these allegations were never formalized into an official complaint.

When The Cut reached out to Mills for that report, he admitted to most of the behavior that was reported and provided an apology. “I am sorry to anyone who heard of this comment and felt pain or offense,” he said. “I am sorry if this comment in any way contributed to discouraging women in our field.” In that same report, the Times audio team vouched for him. “He described it as a profound awakening for him, and a source of great shame and remorse,” Lisa Tobin told The Cut. “He has successfully worked with and for women inside an audio department that is predominantly female — a close-knit and deeply collaborative team.”

That report by The Cut was published in early 2018, about two months before Caliphate debuted. Now, almost three years later, Mills’ appearance on The Daily in the wake of Caliphate’s highly public mistake opened old wounds. Several women in the audio community took to Twitter to make public their own previously unreported allegations of having been targeted by Mills in the past. Even more expressed their broad frustration with Mills’ apparent unimpeded ascendance despite the circumstances.

The social media-facilitated explosion against Mills is illustrative of two things. First, it expresses the extent to which Mills’ specific history of improper behavior remains unresolved among his peers, at least to a point where those who felt harmed by Mills’ behavior could identify some measure of true accountability. Second, it illustrates how there continues to be no proper restorative systems in place, whether structural or social, to remedy the harm of such behavior, period. What are the adequate paths forward for people who feel harmed by someone like Mills? What are the adequate paths forward for someone like Mills? There remain no clear answers for these questions, but that shouldn’t be enough reason to let the subject go. That lack of avenue for accountability, or whatever you want to call it, continues to contribute to a broad feeling that institutions of power — the ones that provide the audio community with its opportunities for employment, resources, and self-realization — will never be made truly just by any “reckoning.”

In some conversations I’ve had about the Mills aspect of this story, there was further anxiety expressed stemming from the fact we’re talking about the Times. Part of this anxiety comes from a recognition that the Times is only set to become an even stronger, larger, and more meaningful employer in the audio business. This is unambiguously true. The Times audio division has hired a crap-ton of people. It now has a sister Times Opinion Audio team that’s hiring even more people in addition to hiring new podcast stars. It even acquired Serial Productions. (Indeed, some expressed reluctance to publicly express their displeasure about Mills because they were afraid it might harm their careers, particularly if they hoped to someday pursue a job at the Times.) But part of that anxiety also seems to be coming from a sense that the Times is supposed to be a moral beacon in a time short with them; that the Times should just be better at this kind of stuff.

Quick pause at this point. So, I’m generally uneasy about writing columns like these, because there is a way in which the positionality of columns about messes like these is one that structurally suggests the columnist to have some kind of moral superiority. To be perfectly clear: I am not morally superior to this situation. As a critic, I gave Caliphate a glowing review when perhaps I should have been more skeptical. I’ve interviewed Mills about Caliphate having taken the Times’ vouching at face value.

With that in mind, I’d like to hit three more things. The first is to simply emphasize that the uproar around Andy Mills matters, as it is a wound that continues to be felt by many in the audio community who were deprived of a good process to work this out. I imagine this might all look like a big social media pile-on from the inside, and maybe some of it might be, but I think it’s more broadly an honest expression that this stuff means something to people. And while it’s been my impression that (almost) nobody is advocating for dismissal or demotion, what folks seem to be pushing for is meaningfully felt acknowledgment that Mills’ past behavior matters. What that acknowledgment is supposed to look like continues to be the struggle.

The second is that these two story threads — the one about Caliphate’s problems and the one about Mills — are interrelated, in the sense that they both speak towards the same institutional dynamic of privileging stars over fundamental process. That said, I also think they should not be read as being threads uniquely about the Times. All that’s happening here is almost certainly happening in every other kind of institution, perhaps on less noticeable (or better hidden) scales. This just happened to be the highest-profile incident possible.

The last thing is this: I won’t pretend to know what the shape of specific remedies should be. I don’t know what mechanisms should be put in place to ensure the Caliphate stuff doesn’t happen again, and I don’t know what process should be installed to effectively mediate things like the stuff around Mills. But my sense is that what people are generally hoping to see is genuine internalization of error. That these mistakes will meaningfully inform every move that comes next.

Amazon to Acquire Wondery

This officially puts a bow on what the Wall Street Journal reported in early December.

Right before the new year, the Bezosian mothership announced its intention to purchase Wondery, the podcast publisher known for its pulpy offerings that also stands as the last big buyable podcast asset of this past generation. The company’s been in the headlines over the past few months as it sought to cultivate an acquisition market for itself, but it’s also been in the news recently for the legal fracas surrounding its founder, Hernan Lopez, a former Fox International executive who was charged last spring by the US attorney’s office in the Eastern District of New York with being part of a major corruption scheme involving global soccer broadcasting rights. Lopez has denied all charges. The case is still on-going.

The acquisition price was not formally disclosed, but a source told the Journal that “it was about $300 million.” The Journal also reported that Lopez will be leaving the company he founded after the deal closes, presumably answering the question of what Amazon thinks about Lopez’s legal situation, after which he will focus on his new family foundation. Wondery’s chief operating officer, Jen Sargent, will take over the company upon Lopez’s departure.

Let’s switch over to Amazon. The acquisition announcement noted that Wondery would be sorted into the Amazon Music division, an addition that comes only three months after the platform first started adding podcast distribution to its offerings. Keep in mind: Amazon Music isn’t the only media division in the Amazon octopus to dabble in podcasting. Its towering audiobooks service, Audible, has long maintained an on-again off-again relationship with podcasts or podcast-like products. For what it’s worth, there doesn’t seem to be much of a master plan here. Instead, the situation looks purely like an opportunistic spaghetti-on-the-wall measure, a gambit to set some assets in place and see what happens.

What does Wondery give Amazon Music? As I’ve written previously, what Wondery brings is scale of reach, at least in theory, though it’s interesting to qualify that the nature of that reach currently only realizes itself over the existing podcast distribution ecosystem. One assumes that part of the point of Amazon Music absorbing Wondery is to increase the former’s key platform metrics, whether it’s user base or time spent on the platform. After all, the fundamental need for Amazon Music is to stay competitive with audio streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music. As such, the first defining puzzle for Amazon Music is to figure out how to extract value from Wondery for its own platform gains in this context — in other words, how to convert Wondery’s fans into Amazon Music devotees. (Insofar as there are “Wondery fans,” of course. Presumably, this is where Wondery’s adventures with app-specific premium subscriptions came in handy.) This conversion effort might mean eventual program exclusivity, but it might very well mean something else. We’ll see what the Amazon Music team tries out.

There’s also the whole thing about Wondery’s other major calling card: its aggressive participation in the podcast-to-Hollywood intellectual property pipeline. I struggle to see how that amounts to anything more than a mild value-add for Amazon Music. Again, we’re talking about Amazon, whose sprawling tentacles include multiple existing positions through the film and television business. So, while one could theorize that there are possible and interesting direct integrations between Wondery’s podcast properties and the Amazon Prime originals business, that IP dimension still feels like stuff Amazon doesn’t actually need in the first place.

I hear what some of you are asking: does all this really add up to $300 million-worth of a payout? Well, that’s never been the framing for this kind of thing. Spotify didn’t pay $230 million to buy Gimlet for what it was, but for what the platform hoped it would become and for the statement it’s making when that much money is whipped out for that new thing.

Plus, it’s not like $300 million is too taxing for Amazon, one of the few companies propping up the S&P 500 in a period of immense financial catastrophe.

Selected Notes…

➽ The team behind Breaker, a fairly nifty third-party podcast app that’s been around for a few years now, is joining Twitter, and the app is shutting down.

➽ I have been informed that Bean Dad drama is technically a subset of Podcast Drama, given that the aforementioned Bean Dad is a prolific podcaster.

➽ ICYMI: the Duke and Duchess of Sussex dropped their holiday podcast special on December 29, exclusive to Spotify.

➽ Speaking of Spotify… From Variety: “Spotify’s Podcasting Problem: Loophole Allows Remixes and Unreleased Songs to Hide in Plain Sight.” Again: YouTube-style ambitions, YouTube-style challenges.

➽ From South China Morning Post: “China’s podcasters wary of censors as popularity grows.” I’m keeping an eye on this, given my general frustration with how podcasting in China has been discussed in the past.

➽ Here’s something interesting: Kerning Cultures, a podcast network based in the Middle East that we wrote about in 2018, has launched a fiction podcast that it’s calling an “Arabic immersive thriller.” The show is called Saqr’s Eclipse, and it’s out now.

In tomorrow’s Servant of Pod… By The Book’s Jolenta Greenberg and Kristen Meinzer are on the show this week. The hook, of course, is that it’s the New Year, which typically brings with it New Years’ resolutions, which is something neither I nor the By The Book duo put much stock in.

In any case, I just figured it was a good time to highlight By The Book, which is a show I really enjoy. If you’re unfamiliar with the show, every episode sees Greenberg and Meinzer pick a different book from the self-help section and live by its tenets for two weeks, after which they evaluate just how useful these books are anyway. As you would probably expect, only some are actually useful, most not so much. Either way, I really enjoyed talking to Greenberg and Meinzer about self-help books, who tends to write them, and what kinds of books in this genre are actually helpful.

You can find Servant of Pod on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or the great assortment of third-party podcast apps that are hooked up to the open publishing ecosystem. Desktop listening is also recommended. Share, leave a review, so on.

Oh, speaking of which. I had the pleasure of doing a bunch of audio spots last month to talk about the ~Year in Podcasting~. Here’s me on Minnesota Public Radio, on Nerdette, on All Of It with Alison Stewart…

… and on Fresh Air, where I put on my best Justin Chang impression.