Is it real or is it fake? Is it a sport or is it an art form? Is the story what goes on inside the ring or what happens behind the scenes? These questions animate any serious discussion of professional wrestling; the key to understanding this American pastime is that the answer is yes, on all counts.

No series has understood this better than Dark Side of the Ring. Billed as the most-watched show in the history of Vice TV, Dark Side digs into the history of professional wrestling for its most controversial and criminal moments, which it portrays with genuine style and considerable compassion. Returning for its third season on May 6, it’s a must for true-crime junkies and wrestling aficionados alike. You don’t need to be a pro-wrestling scholar to find it a gripping, moving watch.

For starters, Dark Side claims lineage from one of the most important entries in the true-crime genre. Filmmakers Jason Eisner and Evan Husney have made no bones about the fact that the stylistic inspiration for Dark Side is legendary documentarian Errol Morris’s 1988 breakthrough film, The Thin Blue Line. That movie’s approach to a Texas murder and the likely conviction of the wrong man for the crime inspired Dark Side’s vivid, noirish reenactment segments, in which actors and wrestlers are filmed in vivid silhouette, portraying important events in each story. It’s a thin line indeed that the series walks: It necessarily requires the portrayal of devastating events without exploiting them, and the shadowy reenactments, coupled with archival footage and extensive first-person interviews, are what make it work.

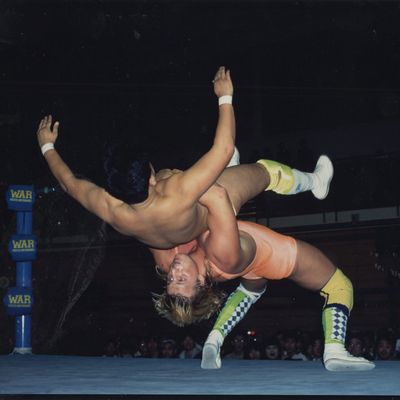

Some of the series’ more lighthearted episodes (relatively speaking) focus on what goes on inside the ring, tackling controversial behind-the-scenes decisions that led to public debacles. “The Montreal Screwjob,” for example, chronicles a successful ploy by the then–WWF management to strip wrestler Bret “Hitman” Hart of his championship in the middle of a match, against the agreed-to script. “The Brawl for All” examines a truly baffling how-did-this-happen series of matches in which professional wrestlers, trained in the art of pretending to beat the shit out of each other, were given the ill-advised opportunity to do so for real, perplexing fans and altering careers forever. “The Life and Crimes of New Jack” details the titular wrestler’s gangsta-rap-inspired persona and in-ring transgressions, which at different times involved the use of a surgical scalpel and a taser on his unsuspecting opponents.

In other episodes, the crimes are genuinely tragic. Foremost among these is the two-part season-two opener, simply — and, if you know your wrestling history, ominously — titled “Benoit.” In what is widely referred to as wrestling’s darkest hour, wrestler Chris Benoit, one of the most technically accomplished performers in the sport’s history, killed his wife and young son before hanging himself in his home gym. The piecemeal discovery of the facts surrounding this horrifying incident led the WWE to air a full-fledged tribute episode to the performer, only to reverse course and virtually erase his career from the history books when the truth came out. Multiple explanations for Benoit’s crimes — roid rage, CTE, an inability to recover from the premature death of his best friend, wrestler Eddie Guerrero — have been suggested; all of them trace back to professional wrestling’s unforgiving culture.

One of the show’s most fascinating leitmotifs is the degree to which wrestlers “live the gimmick” — intentionally blurring the line between performer and performance for added verisimilitude in the ring. For some wrestlers, like “Macho Man” Randy Savage — the subject of the season-one premiere, “The Match Made in Heaven” — the line simply didn’t exist: What you saw on camera was virtually indistinguishable from the bombastic, paranoid life he lived offscreen. Season three kicks off with the two-part story of Brian Pillman, whose “loose cannon” character was reflected both in his reckless lifestyle — a difficult balancing act given his ever-expanding family — and the very real car wreck that shattered his career before his death of a heart ailment at the age of 35. Similarly, “Gorgeous” Gino Hernandez’s fast-living, big-spending character reflected his real-life underworld connections, leading to speculation that he was killed by his criminal associates. (Dark Side tracked down enough of the figures involved to conclude that his death, though tragic, was not a murder.)

In the case of Frank “Bruiser Brody” Goodish, however, the line was a bright one. An absolute monster in the ring, he was known for bloody confrontations with his nemesis, Lawrence “Abdullah the Butcher” Shreve, which would frequently spill out into the stands, terrifying onlookers. But both his fellow wrestlers (Abdullah included) and his widow, Barbara, attest to the fact that he was a thoughtful, gentle giant outside the ring. This fact was lost on the local authorities attending to his stabbing by another performer in a locker-room shower; they at first believed it was all part of the show. Dark Side also hints at the possibility that Brody’s fearsome reputation helped lead the jury to believe his killer’s successful claim of self-defense at the subsequent murder trial.

The promise of genuine, never-before-seen revelations is key to Dark Side’s appeal. “The Montreal Screwjob” episode, for example, features not one but two prominent industry figures — arch-rival producers Jim Cornette and Vince Russo — claiming credit, if that’s the right word, for the most infamous swindle in the sport’s history, for the first time ever. On a darker note, it’s hard to shake the moment when Martha Hart, the widow of wrestler Owen Hart, digs into her archives and produces the chintzy hook that held her late husband aloft during a spot in which he was to be lowered from the arena ceiling to the ring in a harness — the very hook that gave out under a weight it was not meant to hold, sending Owen plummeting to his death in front of a live crowd.

And like any good series, Dark Side has a recurring villain: Vince McMahon, the mercurial WWE CEO. There he is, berating a reporter at a press conference for asking uncomfortable questions about Owen Hart’s death. There he is, wiping Owen’s brother Bret’s spit off of his face after the Screwjob, live and on camera. There he is, helping usher his superstar wrestler Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka through local law enforcement’s questions regarding the death of Snuka’s girlfriend, Nancy Argentino. McMahon has played the villain on camera since the Screwjob went down; as far as Dark Side is concerned, this may once again be a case of a performer living the gimmick.

But whereas many antihero dramas end on a down note, Dark Side frequently concludes with its most uplifting moments. It’s hard not to root for Owen Hart’s widow, Martha, and son, Oje, as they translate his legacy into a foundation helping underprivileged mothers. It’s hard not to root for retired wrestler Kevin Von Erich — the last surviving son of a wrestling dynasty, whose brothers succumbed to suicide and misfortune — as he lives out his life in a Hawaiian paradise, surrounded by nature and the sons who look to him for inspiration. It’s hard not to be moved by Chris Benoit’s surviving son David’s reunion with his slain mother’s family, a reunion facilitated in large part by Dark Side itself.

Dark Side’s success has already spawned something of a cottage industry. In addition to the behind-the-scenes-augmented series Dark Side of the Ring Confidential, Dark Side of Football is slated to take the series’ approach to the gridiron starting on May 13. But the return of the original article is something to be celebrated. It puts a fascinating art form under the microscope, with real cinematic panache and true sympathy for its subjects. Set in a larger-than-life world with all-too-human heroes, it’s about as good as a true-crime series can get.