As one collaborator says early on in Edgar Wright’s new documentary, The Sparks Brothers, if you want to understand Ron and Russell Mael, the extraordinarily prolific minds behind the cult art-pop duo Sparks, it helps to see them through the prism of cinema. The brothers grew up as movie buffs in Los Angeles, gorging on Westerns and the French New Wave, and many of their songs play as darkly comic short films. “Girl From Germany” is a cringe comedy about a Jewish boy nervous about bringing his Teutonic sweetheart home to meet the parents. “Beat the Clock” escalates its premise with the commitment of a UCB sketch. “Tryouts for the Human Race” is a workout jam told from the perspective of 250 million sperm cells.

No surprise then that amid the brothers’ ceaseless recording schedule — from the early 1970s to the late ’80s, they averaged nearly an album a year — the movies would also come calling. And considering the brothers’ fraught relationship with commercial success, it’s no surprise either that these film projects would almost all come to naught. In the ’70s, the Maels were set to star in Jacques Tati’s final Mr. Hulot film, but the project never got off the ground before Tati’s death. The brothers spent much of the late ’80s and early ’90s writing a musical adaptation of the manga Mai, the Psychic Girl with Tim Burton — until Burton lost interest and dropped out, a development that apparently devastated them. It’s entirely possible that a cameo performance in the little-loved 1977 disaster flick Rollercoaster could’ve been their primary cinematic legacy.

But now, slightly accidentally, the stars have aligned for Sparks this summer. June 18 brought the release of Wright’s documentary, a labor of love from a self-described fanboy who was one of many pop-culture-obsessed nerds who gravitated toward the band’s literary wordplay and arch theatrics. The Sparks Brothers functions almost as a living wake, in which artists like Erasure, Duran Duran, and Thurston Moore pop up to offer reverent assessments of the Maels’ influence on subsequent generations of stylish, smarty-pants pop. But the documentary is just the beginning. In July, the brothers’ decade-in-the-making movie musical, Annette, will open the Cannes Film Festival, having been delayed a further 14 months thanks to COVID-19. Considering that 2021 is also the 50-year anniversary of Sparks’ debut album (originally released under the much worse band name Halfnelson), the next few months could blow up their status as — in the words of Wright’s opening narration — pop’s most “underrated, overlooked, and hugely influential” band. It’s not the sort of attention or reappraisal the Maels are used to, but they recognize it’s overdue. Says Russell, “We’re actually glad that somebody else has said it about us, rather than us saying it about ourselves.”

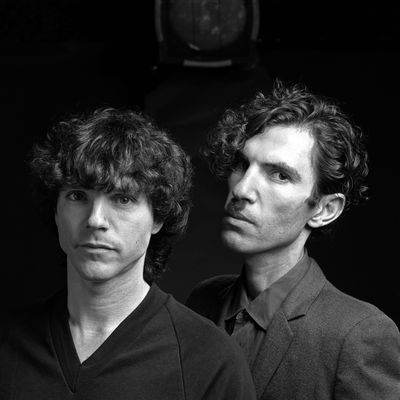

The brothers are Zooming in from their homes in their native Los Angeles. I say “native” because it’s a long-standing joke among the band’s fans that everyone thinks they’re British. I say “homes” because it’s sometimes helpful to remember that the brothers are not actually the inseparable unit they often appear to be. (Though they agree it’s likely that quarantine marked the most time they’ve spent physically apart since Russell’s birth.) Since the ’90s, everyone has also mentioned that the brothers have aged well, and even in their 70s, that remains true today, too. With his mop-top hair and round cherry-red glasses, Russell resembles the world’s cheeriest urban planner. (His secret? Korean moisturizer.) The more sober Ron sports an oversize jacket that resembles a kimono, with his collection of vintage Air Jordans looming high in the background above him. (He quit acquiring them once Michael Jordan retired: “There’s a mystical quality to the shoes when it’s him wearing them, but when it’s just a product, it loses a little of the shimmer.”) For the intensely private Maels, who prefer to keep the bulk of their nonmusical lives a secret, this is as much of a glimpse behind the curtain as you’re likely to get.

Though the doc’s trailer posits them as “your favorite band’s favorite band,” if you are reading this article, there is a nonzero chance you have not heard of Sparks. The film notes that part of the reason the group’s intermittent periods of chart success were so brief is that the Maels often seemed to delight in changing up their sound. They burst onto the scene as whimsical glam-rockers, a vibe that fell flat at home but resonated in the U.K., where they scored two top-ten hits in 1974. When that ran its course, they had a brief flirtation with power pop before pivoting to disco on 1979’s No. 1 in Heaven, a collaboration with Giorgio Moroder that foreshadowed the synth-driven sound of the decade to come. From there, they went New Wave, notching the closest they got to an American hit with 1983’s “Cool Places.” In their later work, they’ve explored electronica, classical, and supergroups. “We’re really restless,” says Ron. “Even though there might have been moments where we tried to build on something, it wouldn’t have lasted very long. It’s important for us not to be stale about things. Our assessment is that other people can sense when you’re going through the motions.”

Just like the British Invasion groups they idolized, the appeal of Sparks has always been rooted in the group’s total aesthetic package. The band’s sound evolves and yet the brotherly personas have remained much the same: Younger brother Russell is the cute one; three-years-older Ron is the silent, mysterious one. (For years, he sported a mustache inspired by either Adolf Hitler or Charlie Chaplin, telling interviewers he considered both of them cartoon characters.) Russell does the singing, while Ron does most of the songwriting. More than one observer has pinpointed the peculiar dynamic of matinee idol Russell speaking his brother’s lines about loneliness, alienation, and erotic obsession. Perhaps to counterbalance this, a few female talking heads in the documentary take pains to note that they actually find Ron quite sexy. “I wish it would’ve happened earlier, but in any case, it was a pleasant surprise,” Ron says of this revelation. Russell, of course, finds it highly amusing.

While Wright’s documentary is full of playful Sparks-ian touches like animation, chyron jokes, and deadpan visual puns, it more or less follows a straightforward chronology, starting with the brothers’ teenage years in ’60s Los Angeles. (One of the film’s most charming revelations is that Russell was a jock in high school.) For the first half, The Sparks Brothers seems to be following a familiar arc: Sparks rise in the ’70s, fade into obscurity in the ’80s, then rise again in the ’90s with the release of their comeback album Gratuitous Sax & Senseless Violins. But then something interesting happens. The movie keeps going, treating the second 25 years of the band’s career with as much reverence as the first. More than anything else, this is the element of The Sparks Brothers the Maels seem most proud of. As Russell says, it shows they’re “still doing work that’s challenging, not resting on the laurels of becoming a nostalgia act.”

Take Annette. In 2009, the Maels collaborated with a Swedish broadcaster on The Seduction of Ingmar Bergman, a rock opera about the legendary director making an imagined sojourn in Hollywood. They dreamed of taking the show around the world, but with 13 different speaking parts, that plan proved logistically infeasible. A few years later, they came up with another idea for a musical, this time a twisted love story. “We love working within the Sparks three-and-a-half-minute song format, but we also like the extended format of a narrative project,” says Russell. To keep the budget tight, the story would have only three main characters: a comedian, a female opera singer, and a conductor. (Russell was to play the comedian and Ron the conductor; despite the brothers’ penchant for drag, the singer was to be played by a woman.) In 2012, the Maels went to Cannes and met Leos Carax, the former enfant terrible of French cinema who had just used a Sparks song in his film Holy Motors. They got along. “There’s a certain kinship to what he does and what we do in a vague sort of way,” says Russell. Afterward, they sent him the script for Annette, also in a vague sort of way. He surprised them by saying he thought it should be his next movie.

The brothers were no strangers to development hell, but this time would prove different. Carax is not one of those directors who has a dozen different projects in the air at once. For years, Annette was the only thing he worked on, as he and the brothers went back and forth refining the script. When Adam Driver signed on to play the male lead in 2016, the Maels were nervous — what if this movie would always take a back seat to his Star Wars commitments? — but also felt vindicated that an actor of Driver’s stature would join such an “uncompromising” project. Annette is almost entirely sang through, and its plot involves a quasi-magical child, which in the finished film is played by a puppet. (Those who have seen it say that musically, the Sparks album it most resembles is 2002’s Lil’ Beethoven, which sees the brothers experimenting with repetition.)

When the Maels visited the set in 2019, they were struck that Annette now existed outside the realm of their own heads. “We’d lived with these scenes for eight years, where I was the character singing,” says Russell. “To see and hear a real actor taking over that role, and singing those parts that we’d become so attached to, that was amazing.” Even better, Carax had managed to open up their vision, making it even bigger than they expected — a rare feat for a pair of artists used to being misunderstood. “We were sitting there with our mouths open the whole time,” says Ron. In a few weeks, the brothers will attend Cannes a second time, to walk the stairs of the Croisette. The men who once asked “When do I get to sing ‘My Way’?” will finally be able to see their names up onscreen, 25 feet tall.

But it wouldn’t be a Sparks song if this moment of glory wasn’t mixed with a little trepidation, at least for a certain segment of the fan base.

“A lot of the people who like Sparks, they feel like it’s this well-kept secret that they’re part of,” Russell says. “If everybody else in the outside world doesn’t want to join in, then that’s their problem. We have this little club to ourselves. They actually don’t want the documentary out there. It’s going to ruin everything.”