It is a strange experience to meet your mirror-image self.

Author and podcast host Roger Bennett is a child of ’80s Britain — a land of economic decay, industrial unrest, and shocking violence. To him, America appeared like a beacon of light from across the sea, and naturally, he moved away the first chance he got.

Meanwhile, I grew up in the sunny Clinton-era suburbs, the son of an American mom and a dad from the U.K. To me, Britain was a place where the bands were all just slightly cooler, where an anxious mumbler like Hugh Grant could be a sex symbol, where cousins I’d never met lived in exotic towns like Nottingham and Macclesfield. (They felt a similar way about me, which led two of them into the unfortunate habit of becoming Philadelphia Eagles fans.) When I got my U.K. citizenship as a teen, it felt like I had been granted entry into an exclusive, underground club.

I first interviewed Bennett back in 2018, when I used his expertise as co-host of the soccer pod Men in Blazers to explain the World Cup. Back then, we mostly discussed other countries, places like Portugal, the home of Cristiano Ronaldo’s nipples, and Morocco, which Bennett called the sporting equivalent of “second cousins at a bar mitzvah.” Now, Bennett’s written a memoir, Reborn in the USA, detailing his youthful fascination with America in hilarious detail. On the eve of July 4, it seemed the perfect time to discuss the special relationship between the U.S. and U.K., which for all their differences are united by an intertwined history, mutually influenced cultures, and — in the cases of Jimmy Savile and Bill Cosby — beloved childhood entertainers who turned out to be sex criminals.

First off: Having spent his life dreaming of America, what does Bennett make of all us American Anglophiles who made the reverse psychological journey?

“I realize, that when you don’t like your reality — and who does like their reality when they’re 15? — the impulse is to create an imaginary world away,” he says. “I’m shocked at how many of the initial wave of readers are like, ‘Dude, England, now that was the place.’ We were all working on parallel lines at different times.”

What is reverse Anglophilia? Ameri-philia? I don’t know.

It’s so funny, there isn’t even a word, is there? Everybody else has one because it’s so curious, you have to be precise. America’s soft power was so pervasive, it just was. You didn’t even need a word for it. It’s like earth, air, fire, water.

The first half of the book goes into great detail about just how crappy Britain in the ’80s was. I’m curious, how much of your love for America came from those specific circumstances, and how much do you think it was innate?

Nature or nurture?

Exactly.

There’s two strands to my love of America. The first was rooted in my family story. Being a Jewish kid in Liverpool, you create family myths to help you survive. The myth of our family was that of my great-grandfather. He left Russia, like millions of Jews, and the story is he was headed for Chicago. Every Jew I knew in Liverpool, they all talked about their great-grandparents as obviously being amongst the low-IQ individuals who saw the one tall building on the local skyline and were like, “We’ve made it to New York City!” They got off when the boat refueled at the wrong stop, and made pennies instead of millions. When you’re unhappy, you build an alternative story for yourself: That was the place we should have gone to. So it was always in our family blood.

And obviously, Liverpool, England, itself, postwar, was in a dark and challenged place. Particularly in the industrial north of Britain, where there was once steel and coal and cotton, it all crumbled. The United States, through soft power, appeared as a beacon of courage, tenacity, and wonder. When everything around me was just drab and flaccid, I watched The Love Boat, Miami Vice, listened to John Mellencamp’s Scarecrow, or Public Enemy, Run-DMC, and it created a parallel universe where the message was, “Life is possible. Happiness is possible. Joy is possible.” So those two threads combined to show there was a world that could be lived in glorious Technicolor, whereas I was very much living in black and white.

It’s funny. I grew up in the ’90s, when Britain had a nationwide rebranding under Tony Blair, who was less a political leader than a marketing exec. For me, it was the reverse. The U.S. was this boring, stodgy place, and it was Britain that was the height of cool and hipness.

“Cool Brittania,” it was fascinating. I was so happy for Britain to, well, not so much find confidence, but shed its absolute self-loathing. When I was growing up, English history was: 1066, we were invaded by the Normans, and then 1966, we won the World Cup. Then that moment got further and further away. It was just a constant cycle of high hopes, “We’re going to win it this time, lads.” And of course, we crapped our pants in front of the world. As a nation, we’re almost conditioned to like that. Don’t take away our losing.

To watch England lose that self-loathing and savor it … There’s an eclectic, diverse, racially complex, textured history, and when Britain shines, it’s wonderful, but there’s still that impulse. All of those bands became big, but then England turned on them and told them they were wankers. We’re still not truly comfortable with success.

The very first line of your book says, “I was raised on American soft power.” Is there anything Americans don’t quite perceive about how our image is reflected abroad? Something that you can only know by seeing it from the other side?

I can’t answer because I don’t know what Americans know. But I know now that the myth of American soft power that I grew up with, is not real. I know that. We know Miami Vice, the Super Bowl Shuffle, is not the real America. The real America has challenges just like everywhere else. But that did not make them unreal to me as deceptions. I think the difference is, to me, they were so powerful. All of them were like sirens calling me to move onto the rocks. They were so un-bloody-believably real.

The myth isn’t real but the emotions they inspire, the power that they have, that is real.

At the end of the book, it really is me trying to work out, right after the election results came out, that if the dream that brought me here, that’s really been the founding myth of my own life, if that dream is not real, then what do I do with it? That’s the driving question of the book.

In other words, how do you reconcile the knowledge of these ideals with the knowledge of all of these historical and modern-day injustices, without denying the power that they have for you and for other people who come here?

I think about it in two ways. The first is best put by Langston Hughes, which is the epigraph of the book, and it’s something I’ve thought a lot about over the last year: “Let America be America again / The land that never has been and yet must be.”

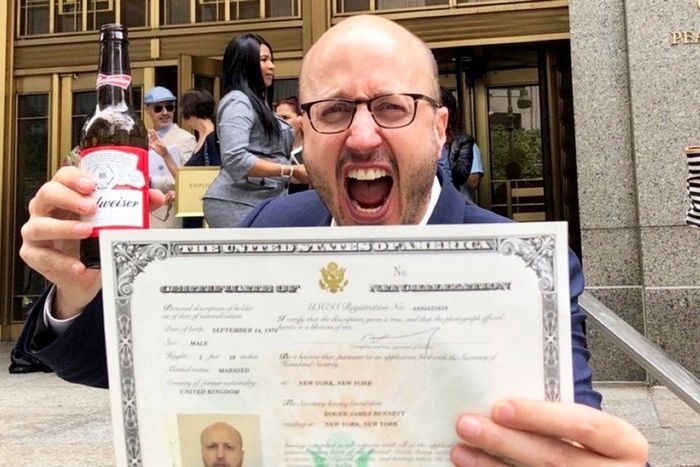

Then the epilogue of the book is what I consider to be the greatest achievement of my life, becoming a newly minted American citizen. Being part of that ceremony, with 147 people from 67 countries, many of whom had crawled to get here. Crawled the deserts, survived conflict, risked life and limb to be there — which made, for me, surviving the odd beating in a late-night Liverpool chip shop seem like nothing in comparison. Experiencing the Oath of Allegiance, in that company, with that energy … It was exactly the same when I voted. I stood by a 93-year-old African American woman in a wheelchair who’d instructed a caregiver to make sure she was first in line. I felt the same joyous, wonderful energy, in that moment, of the right to vote.

Amid those two things, there was the world’s reaction, the parties around the world. Everybody recognizes, “Yes, America, like any country, is not perfect. But the world is a better place when you can dream about America.” That’s ultimately the last spine of the book, and my absolute belief.

You often speak about yourself on the podcast as a miserable pessimist. But these do not sound like the words of a dark, depressive person.

We all learned a lot about ourselves in the past 14 months. We’ve all changed. I do think, in writing this book, I had thought myself as quite a dark human being. Even when you run away from something, which I did from England, it is of you. I do stamp it out, but I realize there is an Englishness that is inside of me still. But I think our show, our podcast, everything we do, I’ve realized I’ve tried to bring joy, optimism, a sense of hope. I am surprised, yes, when I read it. It’s as surprising as looking in the mirror and seeing myself with a full head of hair. What I’ve learned, both from writing the book and the past 14 months of lockdown is, yes, life is dark, which I always thought. But when happiness comes, which it does, even glimmers of happiness, you’ve got to savor them. Make memories with them and dance as if you were at your own kid’s wedding.

When we talk about the U.S. influence on Britain, we usually only talk about it in the context of bad things: the Super League project, Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies. I’m curious, is there an American influence on Britain that has been positive?

Absolutely. So many. God, the first one that comes to mind is Tracy Chapman. The salve to every wound. I remember the concert to celebrate Mandela’s birthday — 600 million people around the world tuning in to Wembley to watch Clapton and Stevie Wonder, and she was filler. She was obscure then, though I already loved her.

Stevie Wonder’s keyboards malfunctioned just before he was meant to go on as the headliner. The organizers just flung out Tracy Chapman because she didn’t need any electronic anything. “Throw up that acoustic person again.” It was a bit like throwing out a poor gladiator unarmed to a lion. This was Wembley at night, 82,000 drunk English people. I had seen what these people were capable of, and the human being I adored most in the world was flung out. She was nervous as hell. The English fans started to boo. They started a chant: “We want Stevie.” And she fired up the beginning of “Fast Car,” a song I love but they’d never heard, and they started to chant over her as if it was a football match. She leant in, and she almost drew confidence from her own lyrics, became more and more of a presence.

Within a minute, she turned Wembley from poised for a beer brawl into an intimate, silent room. It was the most remarkable thing ever. “Fast Car” was then audible in England for the entire summer. The message was, “Take control of your own life. Do not miss that moment. Get out while you can.” And that is a message that came from America. If sirens sang to us, they couldn’t have sang more beautifully than that.

One thing that I noticed from the book is that your voice is the same when you write and when you podcast. Do you write like you speak or speak like you write?

My mum always tells me that I speak as if I’ve got my jaws wired together. So I guess I write as if I’ve got my jaws wired together. I am so blessed to have come from Liverpool. It is a city of blaggers and romantics and storytellers. A lot of Liverpudlians joke that it’s the capital of Ireland, and there’s a massive oral tradition. There’s more comedians that come out of Liverpool than any city in England. A lot of writers. Whatever I do, and I don’t know what I do … I’m English and I’m Jewish, so I’m filled with a double helping of self-loathing. I don’t like to talk about myself. But whatever I do, in the writing or speaking sphere … I’m much more comfortable as a Liverpudlian than I am as an English person.

If you could bring any product or cultural tradition from America into the U.K., what would it be?

When the NFL crashed into television screens in 1982, it was eye-opening for me. English football then was not what it is now. It was mostly played on muddy pitches by angry men who just wanted to kick anything, like the ball or each other, and then have a cigarette and a pie in the pub after the game. The fans largely went to fight each other. They wanted the taste of their own blood in their mouth. It was very tribal, very parochial.

When I saw American football for the first time, it was thrilling. I didn’t understand anything, but the visual passion and joy of it: the touchdown dances, the funky chicken, the color, the pizazz. The year we started watching, the New Orleans Saints were terrible. I expected their fans to do what I was conditioned to see fans do, which was to rise up and kick the crap out of the other fans. Instead, they called themselves the New Orleans Ain’ts and put paper bags over their heads. So the thing I would import from America is that sense of sports as love. Finding joy in winning and losing.

And good pizza. I mean, God, everything in life feels better with good pizza.

What about vice versa? What would you import from the U.K. to the U.S.?

You know, I’m looking at a cupboard filled with Cadbury’s chocolate. I’ve got my tea bags. I’ve got my sticky toffee pudding. I’ve got a fridge full of kippers and haddock. Everything now is so accessible. But other than my lovely mother, and my wonderful, idiosyncratic, deeply passionate father, I cannot think of a single thing that I would like to bring over.

Not even something more intangible?

I do think about the Blitz spirit, the grind and tenacity. But having lived through New York during COVID, no one can surpass the spirit of this city. At the beginning of COVID, I’d wake up at 5, 5:30, and I’d sit in my apartment and look out over Broadway. I always love that hour, where New York feels like the first act of a play in which everything is possible. But at the same time, I knew the city around me was crackling. It was a very incongruent, hard time psychologically for every New Yorker.

Have you ever thought about what you would be doing in England if you hadn’t left?

That’s a frightening thought. The remnant of the class system still held, and there weren’t that many options. One of the joys about America is, you have so many incredible options. Who do you want to be? What do you want to be? In England it was: probably Liverpool. If you’re bold, and you really want to adventure, maybe Manchester. For the truly fearless, you’d move to London, but then you’d probably move back. I don’t even like to spell it out, but it was just the vague thought of the foggy, dry-ice-surrounded future that awaited me. All I knew is I didn’t want it.

One last question: When England plays the U.S. in the World Cup, who do you root for?

Who do you think, mate? It’s not even a qualm. It’s not a Sophie’s choice. It’s the opposite of a Sophie’s choice; it’s Roger’s choice.

This interview has been edited and condensed.