Right now the Museum of Modern Art has an audacious show of 280 Paul Cézanne works on paper that demonstrates that this immensely influential artist took us to the furthest shores of seeing in his drawings and watercolors.

Cézanne drew almost every day for 50 years. By the time he died — in 1906, at the age of 66 — he had produced over 2,000 works on paper. Cézanne said the artist “is merely a recording apparatus for sensory perceptions …” and the “shimmering chaos” around us; he wanted to be “completely absorbed into” the landscape. He was. He doesn’t so much look at and render things in the world as aspirate them, atomize and liquify atmosphere, light, and form. Cézanne’s drawings record the split second before we make sense of, organize, identify, and define what we see — before we make metaphor, analogy, and meaning, when we are just seeing. It’s a kind of sensual nano-physics. His drawings are two-dimensional panic rooms where he pieces things together without fixity. We see torrents of line, snail trails of curlicues, ambiguous quivers and curves, fitful scrims and skeins that stay on the surface but nevertheless suggest depth. You start to see morphology itself — how the biomass of the world comes into being for us. The results were like a glass shattering in art history. Author Philip K. Dick talked about “contact lunacy.” Cézanne gives us contact lucidity, organizing all this on a surface in such a way that allows us to glean an estrangement from seeing. It fills you like perfume.

From the 1850s onward, Cézanne’s art was a protest against what he considered to be the dead-end, dummy idea of perspectival space that was associated with the 19th-century academy — the counterfeit sincerity, pompous vacuity, moral dryness, polite portraits, and false pieties of painting that then filled the official salons. Cézanne wanted to cast out the 500-year-old demons of pictorial illusionism, naturalism, and romanticizing. He only wanted to record his subjective experience of the graphic field, particles of light, structures and spaces between things.

As with Velázquez and Rembrandt — both of whom have more humanity and emotion in their art — Cézanne is hard to grasp. I devoted a whole section of my book How to Be An Artist to the incommunicability of his resistant art. It took me until my early 50s to be smote by Cézanne. Now I love him. While he is part of a gigantic continuum of modern painting, he also stands alone. He worked at the same time as the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. They loved his art; he loved theirs. Yet the differences are enormous. The surfaces and spaces of Seurat and Signac, for example, are ordered, reposeful, trance-y, scientific. We luxuriate in their making and perceive the method and theories in use. Ditto the evenly applied-all-over distribution of individual marks in Monet, Gauguin, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Pissarro (to whom Cézanne owes the most). For those artists, every area of a painting is given equal importance and retinal energy. Everything is finished — or turned up to 11 in the case of Van Gogh. Things have perceptual-conceptual-spatial continuity and are still tethered to naturalism and illusionistic space. By contrast, half of a Cézanne drawing may be sparked to life abstractly in areas of totally blank paper. Space as we know it begins to collapse. Adorno — always a bit of an undertaker, always declaring things over — remarked that “With Cézanne, landscape itself comes to an end.” For his part, Cézanne thought the opposite — that, “alas!” before him “landscape has never been painted.”

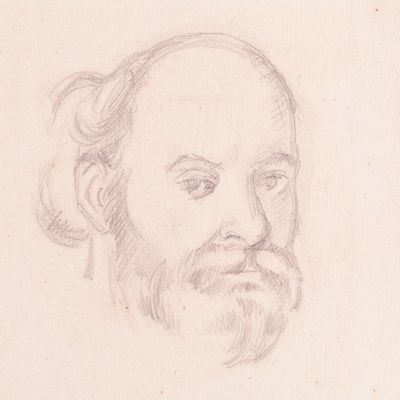

Cézanne was born in 1839 in the South of France to a banker father. He lived like an itinerant, moving from studio to studio, town to city, house to apartment, always looking, working. He said he wanted to die painting, and he did — collapsing while he was painting in the rain and dying days later. Though he was disdained by the traditionalist academy, he was famous among his colleagues and sold art to other artists. Matisse called him “a God.” Picasso deemed him “the father of us all.” But he was gruff, incredibly shy, and looked, one colleague said, like a zinc miner. He so revered Manet that he was afraid to speak to him. Manet loved Cézanne’s work but once refused to show with the uncouth painter who spoke with such a profound provincial accent that many could not understand what he was saying.

MoMA curators Jodi Hauptman and Samantha Friedman allow us to grasp all of this. My recommendation: fight the fatigue of so many framed works. Select just three or four drawings in each of the eight galleries — any three or four. You will be confronted with Cézanne the seeing, recording machine. It’s almost inhuman, maybe monstrous. He almost denies humanity in his art, staking everything on recording whatever pathos already exists in the world before we name it. He said he wanted “solace without passion.” Buddhism calls this nirvana.

The show is installed by subject, and Cézanne returns over and over to one or another of his mundane subject matters: landscape, still life, bathers, skulls, and people. He made 80 bather paintings, 40 paintings of Mt. Sainte-Victoire (a mountain eight miles from his birthplace in Aix-en-Provence), and over 100 still lifes (50 with apples). He famously said, “I will astonish Paris with an apple.” He made 56 drawings of his wife, who is always poised, tilting, acquiescing, subjecting herself to his gaze. Really, there’s not much difference between her, an apple, a mountain, or a skull. His people, places, and things are just forms, masses, weights, and measures. He made 136 drawings of his son, but most of those are of him sleeping. He must have been a pretty distant husband and father.

It makes sense that someone who inhabited and rendered that 50,000th of a second of vision before thought had to slow down time so much that a portrait could take 100 sessions or a landscape could take years. An artist who lived just below Cézanne’s studio reported often hearing him pacing on the floor above — he would make a mark, sit down for 20 minutes, get up, put down another mark, sit back down, and so on. Cézanne created a time machine that slowed the moment when everything glitched and stood still.

Consider any work; study how charged the blank space might be. He never outlines things, but objects always form as shapes—dissolving, overlapping, and interweaving one another. Light comes from all different directions at once. A shadow is cast one way, then another. You see an apple from above and below and left and right. Middle, close, and far space intermix, coalesce, and flip-flop. His graphic field is like a vibrating string. Notice, too, that the two biggest claims about Cézanne don’t stick. It’s always said no one painted a more solid apple than he and that there’s this enormous density, weight, and gravity holding his world together. On the contrary: Cézanne’s objects and spaces are filaments; they shift and oscillate. Nothing is solid or stays in place. They are made of pirouettes of squiggles, squalls of color, lines always in motion. Everything is always wobbling. Almost all of his horizon lines make no sense at all and are broken. You are seeing some mitochondrial thread that moves in swells and subtle cadences of energy. This imparts a pictorial amplitude and visual grandeur to whatever he’s drawing. Cézanne said, “Paint it as it is.” Cezanne rendered this it as is as it ever was.