Hollywood has a long history of making beloved movies about the backstage machinations of Broadway. A short list would include films as various as Warner Bros.’ Depression-era fable 42nd Street, Vincente Minnelli’s The Band Wagon, Mel Brooks’s The Producers, Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz, and, at the head of the class, Joseph Mankiewicz’s acid-tinged valentine to Broadway’s postwar golden age, All About Eve. They were mostly made in Los Angeles. But some of the best films about the Broadway theater are documentaries made in New York and not nearly as well known as they should be, in part because they have been only sporadically available (if at all) on commercial video. They were the work of D. A. Pennebaker, the groundbreaking filmmaker who died at 94 in 2019 and whose eclectic subjects spanned from Bob Dylan in the late ’60s (Don’t Look Back) to the first Bill Clinton presidential campaign (The War Room).

Two of his exemplary Broadway films, Jane (1962) and Moon Over Broadway (1997, co-directed with Chris Hegedus), chronicle productions from their hopeful geneses to their disillusioning opening nights. They have been overshadowed by Original Cast Album: Company (1970), Pennebaker’s fly-on-the-wall account of the marathon making of the Columbia recording of the musical that rebooted Stephen Sondheim’s career six years after his previous Broadway musical as composer-lyricist, Anyone Can Whistle, had flamed out in a week. Despite often falling out-of-print over the past half-century, this 53-minute film has survived as a semi-underground classic and as recently as 2019 inspired a Documentary Now! parody, spearheaded by John Mulaney. This month, at long last, our indispensable curator of classic cinema, the Criterion Collection, is reissuing the Pennebaker original in a sumptuous restoration.

For so compact a film, it is full of finely etched portraits of the characters at hand, especially the young Sondheim and the original ensemble cast, led by Dean Jones as Bobby, a Manhattan bachelor whose many married friends alternately press him to join their ranks of the semi-happily wed and offer graphic examples of why he had better look hard before he leaps.

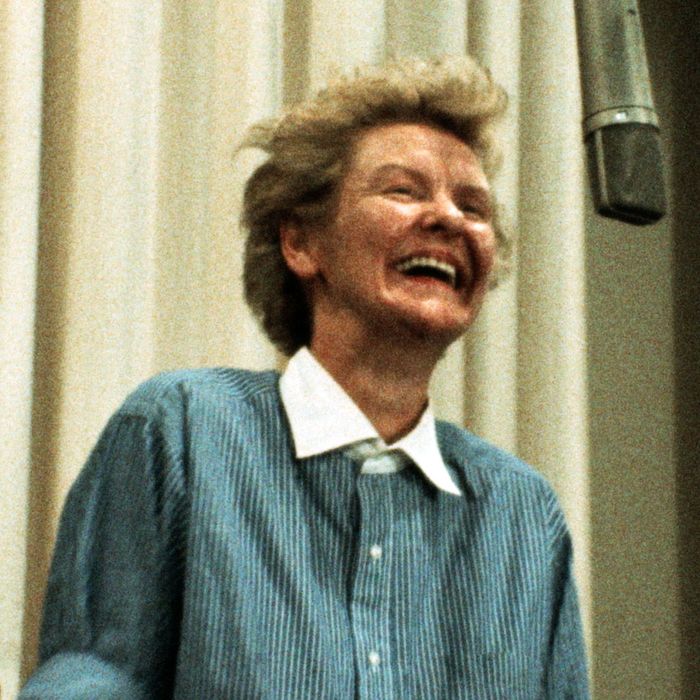

The most sardonic of those friends, of course, is played by Elaine Stritch, whose travails while recording her big number, “The Ladies Who Lunch,” are the dramatic highlight of the documentary and a big part of why the film and Stritch herself have endured as objects of cult devotion. At the time Stritch opened in Company, her career had been flagging; her two star turns in Broadway musicals, both in flops, were a decade behind her, and her alcoholism was no secret. She left the show a year into its 20-month Broadway run, and it would be more or less a quarter-century before the late-in-life renaissance that led to her steady employment in the theater, film, television, and cabaret. It’s the long afterlife of Pennebaker’s enduring portrayal of her breakdown on-camera in the wee hours that kept the memory of her vital spark alive during her many dark years. (After her comeback, he would co-direct a film adaptation of her one-woman stage show, Elaine Stritch at Liberty, in 2002.)

I interviewed Sondheim and Jonathan Tunick, the brilliant orchestrator who collaborated on Company and most of the Sondheim classics to follow it, for a video that accompanies the rerelease of the documentary. Three Sondheim shows in New York were among those shuttered by COVID: the recently opened Ivo van Hove revival of West Side Story; the CSC revival of Assassins then in preproduction; and the new revival of Company, just starting previews on Broadway, in which, as conceived by the British director Marianne Elliott, Bobby is repurposed as a female Bobbie. (Unlike Bobby, she also has a biological clock to contend with as she weighs the joys and perils of marriage on her 35th birthday.) Company and Assassins are now on the verge of reopening, the virus willing.

My own personal history with Sondheim began roughly when Company did. As a drama critic for my college newspaper, I had seen its first public performance, in its pre-Broadway tryout at the Shubert Theatre in Boston, in the spring of 1970. The show’s epic final number, “Being Alive,” so powerfully delivered by Jones, had yet to be written. Even now, having seen countless revivals since, including the gender-reversed version in its London debut nearly three years ago, I still remember the high I experienced at that first viewing in Boston: the jangling pulse and infinite variety of the score and lyrics; the daring refusal of George Furth’s book to offer any narrative that might be called a plot; the aggressive pitch of producer-director Hal Prince and the choreographer Michael Bennett’s staging; the stark Mies van der Rohe architecture of Boris Aronson’s set. Despite being confined to a windowless recording studio, Pennebaker’s film is remarkably evocative of the whole enterprise.

I met Sondheim a year after I initially saw Company, when I reviewed his next show, Follies, in its Boston tryout. A year later, when I was living in London during a postgraduation gap year, he invited me to watch a rehearsal and then the opening of the West End production of Company at Her Majesty’s Theatre. It was a duplicate of the Broadway original with a mixture of imported New York cast members and Brits. The premiere was a triumph for Steve and Stritch, who celebrated by getting plastered at the opening-night party at the Inigo Jones restaurant in Covent Garden and barking savagely at anyone who crossed her path.

When I revisited Company’s early days with Steve and Tunick, it was the December Sunday after Thanksgiving weekend, just as I was starting to venture beyond the immediate neighborhood of my apartment uptown. I decided to do my end of the Zoom at Criterion’s empty office in Union Square, where a crew of two had organized a COVID-protected environment. Like most people I know, I have few jubilant memories from the long hibernation, but seeing Steve, even if on a monitor, is one of them. Fresh, feisty, and funny in his 90th year, he was as charged up about Company, both the musical and the documentary, as if he had written the show yesterday. Though I have talked with him about Company ad infinitum over the course of our friendship, including in public conversations, here he was, still adding juicy new details to the historical record. The interview went on well past an hour, and, at my selfish insistence, drifted irrelevantly into Follies as well.

But that’s another story. When I left the Criterion office, it was chilly and starting to get dark. I decided to walk uptown toward home. The Manhattan that Steve writes about in Company — the “city of strangers” where people “find each other in the crowded streets and the guarded parks / By the rusty fountains and the dusty trees with the battered barks” — was still locked down. But for now, my usual pandemic despair had lifted, so elated was I by having spent the afternoon in intense virtual contact with Sondheim’s teeming New York, as lyrical and poignant today as it ever was. How lucky we are that D. A. Pennebaker caught the lightning of its creation at the very moment when it was being bottled.

Jonathan, Steve has called you the greatest orchestrator for the theater. You’ve worked with so many people. You’ve done movies. You’ve done television. What’s distinctive about working with Steve?

Jonathan Tunick: The easy answer is his intentions are clear. When he presents a new number to me, I’ll ask a few questions, often perfunctory. I tend to get it.

Stephen Sondheim: One of the reasons he’s the best orchestrator for the theater is he has a sense of drama, of what’s going on on the stage. He isn’t just interested in the sounds. He is interested in enhancing the play, and that’s relevant to what he’s saying — my theatrical and dramatic intention is clear, which is something I was taught by Oscar Hammerstein and Arthur Laurents to do.

J.T.: There are some entities that describe my job as “music orchestrated by,” and that always annoys me. I feel I orchestrate more than the music — certainly the lyrics, and maybe other things as well. I’ve been known to consult with the lighting designer. I remember being stuck on an ending once, but I went to the lighting designer and said, “How are you going to light the ending?” And whatever his answer was, it helped me decide what I was going to do with that ending. I’ve described orchestration as lighting for the ears. It’s more than just music.

Many people don’t know how the collaboration between the composer and the orchestrator works. Could you talk about that a bit?

S.S.: I suspect every combination is different, but with Jonathan and me, I write for the piano. It’s my only instrument. I know nothing about orchestrations. I play it for Jonathan in person, and he orchestrates from the feeling of the way I’m playing the piano. I don’t choose any instruments. He does all of that. I suspect it’s very hard to orchestrate because the figures and textures are so pianistic. My favorite example is “Another Hundred People,” which is written as a toccata. It’s a strict approach to piano writing.

J.T.: Alternation of notes is very easy to do on the piano. The hand can rock back and forth. This can be done on orchestra instruments, but it isn’t comfortable, especially when it’s very fast. If you take the string instruments, they create sound with a back-and-forth motion with the bow on the strings. So it’s much easier for them to repeat notes, which is kind of awkward to do on the piano. So if I see the rocking rhythm on the piano and I’m writing it for strings, I’ll probably change it to repeated notes.

As we know, recordings are often sweetened from the theatrical version, in that instruments are added and adjustments are made for the recording.

S.S.: Jonathan made a decision on what he wanted to do in terms of enlarging the orchestra.

J.T.: It was common practice to double the size of the string section for the recording — every cast album did that. Typically, a Broadway show had six violins, two cellos, and maybe two violas, and you would record with double that number. And we did it on Company as well.

S.S.: Another thing — this was in the days of LPs, meaning there was a limited amount of time you could put on one side of a record. So you have to say, “Sorry, take a minute out.” If possible, you don’t want to throw out an entire song. Although that happens, as it did on the Follies record.

J.T.: You might want to trim out 16 bars of underscoring that make a lot of sense on the stage but are rather redundant on a recording. It has to be like surgery, so you don’t see the scar.

S.S.: [Record producer] Tom Shepard is a composer and musician. If he and I were looking to cut 30 bars, together we could figure out how to get from bar one to bar 16 to bar 37. I love to work on the end of a song. I always like to know what the end is going to be, lyrically, musically, whatever.

J.T.: It’s fascinating you say that, Steve. We’ve never talked about this. I like to work backwards from an ending, too, in an orchestration. I was taught at Tamiment by the great Milton Greene, and he gave me sage advice. One was to write the ending first because that way, if you don’t get to finish the orchestration, at least we’ll have an ending for applause. I found it a good way to work, because a good ending will show me what a good beginning should be.

S.S.: Absolutely. Also you’ve got to learn to save your resources. You don’t want to give everything away in the 16th bar when you want to use it at the end.

Even when you listen to subsequent recordings of Company, of which there have been several, it seems to me this is the definitive recording. Take Dean Jones, who played the lead, but left the show fairly early on in New York. So few people saw him do it.

S.S.: The best “Being Alive” he ever did is on this recording. That’s the best because he was trying so hard, and he didn’t have confidence in his voice. And you can watch it. There’s a close-up of him, and he’s practically sweating the notes out.

We have to move on to the inevitability of Elaine Stritch, who plays one of Bobby’s friends, Joanne. Stritch had been in unsuccessful musicals like Noël Coward’s Sail Away. This was a comeback for her. Steve, when you asked the playwright, George Furth, who the character Stritch was playing was, he said, “It’s Stritch.”

S.S.: I started to write a song for the character, Joanne, because like Stritch, she was brought up very upper class, as opposed to what we know about Stritch when you talk to her. That was important to George because he based the character on her. I wrote a song. I wrote a draft of a lyric called “Crinoline,” which was about how she is really old-fashioned although she is this hip, cuss lady. So I thought, Okay, what’s the action of the scene? She’s getting drunk, so I wrote something called “Drinking Song,” which is in fact “The Ladies Who Lunch.” We changed the title later.

Elaine liked to drink. As a matter of fact, she was a bartender in between jobs. George liked to drink too, and they would go out. They were out one morning, and it was approximately 4 a.m., so the bars were closing. They got to a bar, and she looked through glass doors and, indeed, the chairs were on the tables. And she knocked and knocked and knocked on the glass door until finally the bartender had to let her in. He said, “I’m sorry, we’re closed.” And she said, “Just give me a bottle of vodka and a floor plan.”

Why was “The Ladies Who Lunch” done so late in the session?

S.S.: It was supposed to be done early; the last song to be recorded was to be “Being Alive.” Dean Jones was something of a diva, as it turned out. He said, “I’m having trouble with my throat and I want to take a break. We’ll do another take later.” That kind of behavior. At the lunch break, we were in a diner nearby. Dean was complaining that his voice wouldn’t be usable at ten in the evening. Elaine said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll sing at the end of the day. And you sing in the morning when your voice is fresh.” He said, “Really?” She said, “Yes.” He said, “Okay.” She gave him her spot. So she sang at ten in the evening. And that’s when the dam fell.

From there, we witness her breakdown onscreen. I want to hear both of you talk about what happened in all these takes that might not be visible to someone seeing the condensed version in the documentary.

S.S.: The major thing to look for is what happens to a singer’s voice if they drink. Elaine was a performer with great stage fright, and she would always get a nip offstage to get her courage up. And if she had too many entrances, too many nips, the voice started to go. Which is what happened. She had a bottle of brandy in her dressing room at the recording studio, and during the day she’d take a little nip every now and then. So by 10:30 in the evening, her voice was in rocky shape. In a number like that, it’s not production of the note — it’s the attitude towards the note, and that requires having a completely usable voice and courage. The more she tries, as you see, the less she was able to do it, as often happens.

J.T.: Another issue with Elaine, I think, was the fact that she was very mercurial and the slightest thing would set her off. I did most of her arrangements, and I found that in a rehearsal, if someone made a noise in the audience, if the lighting was a little different, it would throw her off. She’d lose the beat. She’d forget the words.

S.S.: Confidence was not her middle name.

When she was having her problems, was everyone involved with the recording aware that she was drinking?

S.S.: No. Look, what happened was she started recording the number and Pennebaker started to pack up because he was running out of film. As he got halfway to the exit door, he suddenly saw what was happening: that Elaine Stritch was having a breakdown. He turned right around and started to photograph. That’s what happened.

We sent her home. She came back two mornings later, ten in the morning, bright as a button, and did it in virtually one take.

I noticed too when she came back, she’s in full makeup, like she’s ready to land it — and for the camera, not that that was her motive. But looking at the film again, one thing I’m conscious of is that Elaine is quite aware of the camera. She always had her eye on it.

S.S.: Oh, that’s her motive. Sure it is. Why not? I’ll add one anecdote about Elaine. When we were in Boston, she couldn’t get a handle on “The Ladies Who Lunch.” That number is designed to really excite an audience, and she sang it okay. I was in the hotel room writing “Being Alive” when Hal called me after a matinee. He said, “She got it. She got it. I wish you’d been there. It was thrilling, and the audience was wild. You got to see it.” I said, “I’ll come in tonight.”

So I went in the evening, and sure enough, she did it great. I went backstage afterwards and I said, “Elaine, that’s the way it should be done. Thank you so much. It was just wonderful.” The next day I’m back at the hotel and Hal calls me at 11 in the evening after that night’s performance. He said, “Ugh, she lost it. It was so terrible tonight.” I said, “God, I don’t know. I told her how wonderful it was.” He said, “You what?” I said, “I went backstage.” “You told her she was wonderful? You idiot.”

Interview has been edited, condensed, and excerpted with permission from The Criterion Collection.