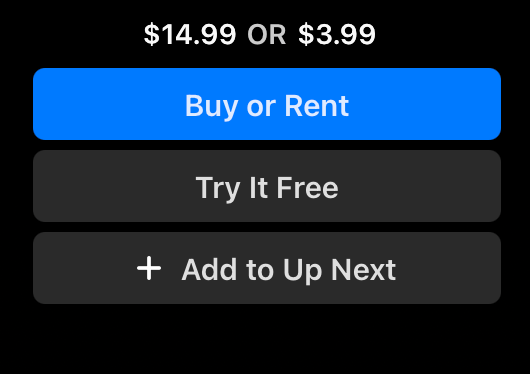

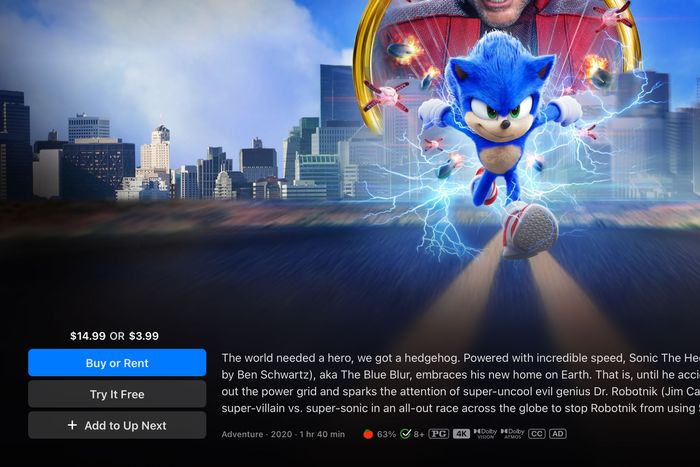

One of the biggest, most beveled companies on the planet is in new legal trouble, courtesy of its own digital retail business. Apple was sued last week in Buffalo, New York, in a class-action alleging deceptive practices and false advertising over its use of ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ and ÔÇ£rentÔÇØ buttons. The plaintiffs argue that saying you can buy or rent anything on the platform is ÔÇ£false and misleading,ÔÇØ because when AppleÔÇÖs licenses for its featured content expire, so does yours, and it ÔÇ£must revoke the consumersÔÇÖ access and use of the Digital Content without warning.ÔÇØ The suit alleges that AppleÔÇÖs done this ÔÇ£on numerous occasions,ÔÇØ using screenshots and citations of the Sonic the Hedgehog filmÔÇÖs pricing to make its case.

ÔÇ£The reason people get so pissed off when their stuff disappears is because they thought they got to keep it,ÔÇØ says Aaron Perzanowski, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University and co-author of The End of Ownership, who follows cases like this one. Perzanowski has worked for years on projects including his book and on legal papers like ÔÇ£What We Buy When We Buy Now,ÔÇØ which explore an argument similar to the one at the heart of this lawsuit. ÔÇ£We came back with what we thought was very, very clear evidence under the kind of standards that you would need to establish in court that Apple and Amazon and companies like them were engaged in a massive, multibillion-dollar false-advertising scheme,ÔÇØ around their transactional language and what customers took them to mean, he says. Vulture asked him to break down the details of this lawsuit, get his opinion on why itÔÇÖs a big deal for digital ownership, and why itÔÇÖs been brought in New York after a similar suit against Amazon was dismissed a few weeks ago.

You DonÔÇÖt ÔÇ£OwnÔÇØ That Song You ÔÇ£BoughtÔÇØ

And neither does Apple, which is kinda the point here. Apple is bound by licensing agreements which stipulate how and when it can sell songs, books, movies, TV shows, and other media on iTunes or other digital storefronts. ÔÇ£Defendant [Apple] can never pass title to the purchasing consumer,ÔÇØ the suit argues ÔÇö unlike a Best Buy or a Target, which sell you a physical item you can carry out, hold onto, liberally loan out to friends, or pass down when you die. ÔÇ£Accordingly, when a licensing agreement terminates for whatever reason, Defendant is required to pull the Digital Content from the consumersÔÇÖ Purchased Folder and it does so without prior warning to the consumer.ÔÇØ

All this amounts to deceptive business practices, false advertising, and unjust enrichment on AppleÔÇÖs part, the suit claims, because if Apple didnÔÇÖt own that copy of Montero anyway, it couldnÔÇÖt ÔÇ£sellÔÇØ it on iTunes in the first place. ThatÔÇÖs the argument anyway.

Amazon made a big deal out of this over a decade ago with ÔÇö of all books ÔÇö 1984. The company remotely deleted unauthorized copies of the book off of customersÔÇÖ Kindles and got sued by a high schooler, ultimately settling for $150,000. ÔÇ£Amazon has just proven that when I buy a book on the Kindle, I donÔÇÖt really own it,ÔÇØ the student Justin Gawronski said in July 2009.

The same applies to Apple today, Perzanowski says. ÔÇ£TheyÔÇÖre promising people one thing with the language of ÔÇÿbuyÔÇÖ and ÔÇÿpurchaseÔÇÖ and ÔÇÿownÔÇÖ that they use to promote these products. Then they werenÔÇÖt delivering on that promise.ÔÇØ

Bye-Bye, ÔÇ£BuyÔÇØ

Most of us probably donÔÇÖt think too critically about what Apple does and does not own when click on the ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ button, but the companyÔÇÖs lawyers have poured plenty of billable hours into lengthy documents explaining it in opaque contract language that we all ignore when we sign up for iTunes or rent a movie on Prime Video. (The Apple Media Services terms and conditions, last updated in September 2021, is 8,005 words long.) ÔÇ£Putting aside legal knowledge, just the way these things are written is, by design, hard to understand,ÔÇØ Perzanowski says.

ÔÇ£Buy,ÔÇØ on the other hand, is a sleight of simplicity ÔÇö a single-syllable, active-trigger verb that can squeeze itself into any UX, no matter how complicated. We click the button and trust that we own it. ÔÇ£Unfortunately for those consumers who chose the ÔÇÿBuyÔÇÖ option, this is deceptive and untrue,ÔÇØ the lawsuit states between screenshots and citations of Sonic the Hedgehog. ÔÇ£Rather, the ugly truth is that Defendant does not own all of the Digital Content it purports to sell.ÔÇØ It goes further, calling out the fact that in the case of Sonic, Apple is ÔÇ£sellingÔÇØ a virtual copy of the film for $5 more than TargetÔÇÖs $9.99 physical copy ÔÇö a seller ÔÇ£actually passing title to such property forever.ÔÇØ

ItÔÇÖs not as though there arenÔÇÖt alternatives to ÔÇ£buy.ÔÇØ PerzanowskiÔÇÖs done studies on how consumers react differently to digital storefronts when they encounter a ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ versus ÔÇ£licenseÔÇØ language, and how adding more transparency to transactions can improve customer experience. HeÔÇÖs also noticed how newer services like Disney+ ÔÇö which donÔÇÖt have years of customer indoctrination on a storefront to account for ÔÇö eschew ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ altogether when they introduce digital retail onto their platforms.

ÔÇ£I got an email from Disney a while ago, and it was like ÔÇÿAdd these movies to your collection,ÔÇÖÔÇØ he recalls. ÔÇ£A lawyer looked at this and said ÔÇÿDo not use the word ÔÇ£buy.ÔÇØ Do not use the word ÔÇ£purchase.ÔÇØÔÇÖ ÔÇÿAdd it to your digital collectionÔÇÖ is a good way I think of avoiding the potential problem that Apple and Amazon have.ÔÇØ He also suggests ÔÇ£addÔÇØ or ÔÇ£save for later,ÔÇØ as more neutral options. Apple could also replace ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ with ÔÇ£get,ÔÇØ as it has in the past. But ÔÇ£none of them are elegant,ÔÇØ at least not as much as ÔÇ£buy.ÔÇØ

AppleÔÇÖs Lawyers Have New York Trade Law to Thank

ItÔÇÖs also not as though Apple isnÔÇÖt already sensitive to linguistic nuances that come with digital storefronts. It had to settle a $100 million class-action after being sued in 2011 over how it touted ÔÇ£FreeÔÇØ apps on the App Store that require in-app purchases. (Now it says ÔÇ£GetÔÇØ when you go to download ÔÇ£freemiumÔÇØ apps like Candy Crush Saga.) Apple is a trillion-dollar company, and a similar ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ button case brought against Amazon in California was thrown out recently, but New York comes with crucial advantages in its trade laws.

ÔÇ£In most states, to make your false advertising claim, you have to prove not only that youÔÇÖve been damaged by the false advertising, but youÔÇÖve got to show how that translates to some sort of financial harm,ÔÇØ Perzanowski says. ÔÇ£New York law sets whatÔÇÖs called a statutory damage amountÔÇØ for both false advertising and deceptive trade practices. The damages for each alleged claim, respectively, are set at $500 and $50 per transaction.

Put more bluntly, New York makes it easier to take Apple to the bank. If 200,000 New Yorkers grabbed a few $5.99 movies or $1.29 songs on iTunes over the past three years (the statute of limitations), and those transactions were multiplied by $500 and/or $50 a pop, well, Perzanowski joked that heÔÇÖs not the best at math, but: ÔÇ£Pretty quickly in a state thatÔÇÖs as big as New York, weÔÇÖre talking about billions of dollars in damages.ÔÇØ Excelsior!

Of course, thatÔÇÖs if Apple chooses to fight and loses. He thinks that if things go well for the plaintiffs, the most likely scenario is the trillion-dollar company settles: ÔÇ£Apple is going to say, ÔÇÿWe have a significant percentage of all the money on planet Earth, how much does it take for you to go away?ÔÇÖÔÇØ

HeÔÇÖs not ruling out Apple changing the ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ button to something like ÔÇ£get,ÔÇØ but heÔÇÖs not optimistic about Apple changing its stance on ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ language in general. ÔÇ£One, I donÔÇÖt think theyÔÇÖd ever get the copyright holders to agree to that,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£And two, from their perspective, at least right now, thereÔÇÖs probably not enough market demand for those kinds of features.ÔÇØ

Apple has also grown far beyond just being a hardware company also selling digital stuff. Its newer business gets nothing out of a ÔÇ£buyÔÇØ reimagining. ÔÇ£They donÔÇÖt want people to lend the new season of Ted Lasso to their neighbor,ÔÇØ Perzanowski says. ÔÇ£They want their neighbor to sign up for Apple TV+. So I think itÔÇÖs probably even harder for them now than it would have been 10 or 15 years ago to make that move.ÔÇØ

Whatever happens will take time. ÔÇ£If youÔÇÖre Apple, you want to slow walk this. You want to get as much distance from the allegedly deceptive behaviors. You want to make it as costly, as expensive as possible for the class-action lawyers,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£The filing of the complaint is, if not step one, incredibly early in this process. I think itÔÇÖs gonna take a while before we can see how the courts are likely to respond.ÔÇØ

If you subscribe to a service through our links, Vulture may earn an affiliate commission.